|   |

|   |

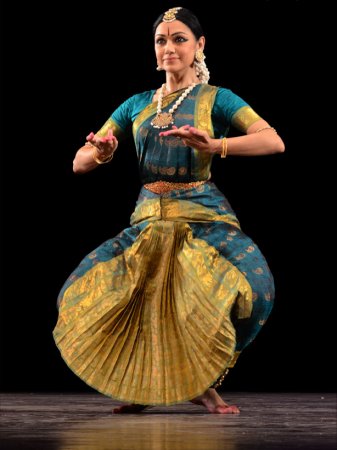

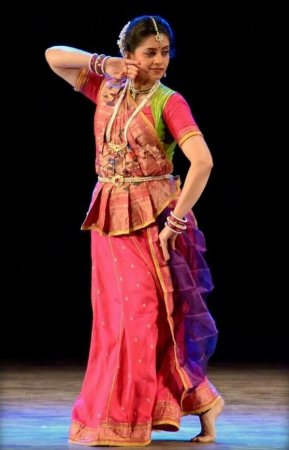

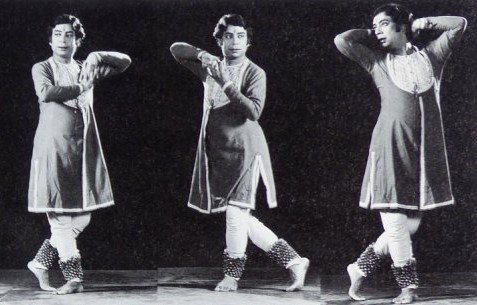

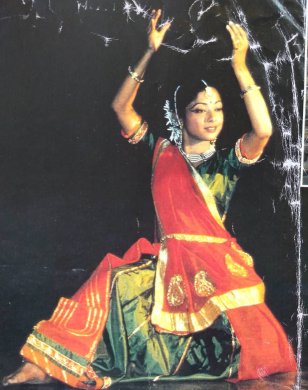

e-mail: janakipatrik@gmail.com UPAJ - Part II - NRITYA (Section # 2) November 26, 2023 UPAJ - Part II - NRITYA (Section # 1) ELEMENTS of IMPROVISATION 1. The Kathak body stance & stage conventions  Shambhavi Dandekar (Courtesy: Shambhavi) Kathak has origins in the village storytelling style katha vaachak - literally meaning "story speaker" - from the Sanskrit root vaak - speech. Kathak's lingering folk elements contribute to the informality of many of Kathak's storytelling techniques, and to the ease with which performers can improvise. Performed with an upright torso carried on straight legs and loose knees, Kathak can cover space with an un-stylized gait, which is close to ordinary human movement. With the continuity of its upright stance for both nritta and nritya (pure dance and storytelling), Kathak can seamlessly transition into the distinctive gaits of all kinds of characters in its stories, uninterrupted by the need to return periodically to a style-imposed position such as Bharatanatyam's araimandi , the "half-sitting" pose , or Odissi's tribhanga - "thrice-bent "- pose .  Rama Vaidyanathan (Courtesy: Rama)  Ileana Citaristi Photo: Avinash Pasricha I am not suggesting that any of these three fundamental postures, of these three distinctly different classical Indian dance styles, is better than any other. I only point out that they are very different in appearance, and also very different in the degrees of formality, which the postures in and of themselves project. In addition, performing in the least stylized of India's classical dance forms, Kathak dancers often establish an informal familiarity with the audience, approaching the microphone to narrate the basic outline of a story and to demonstrate some of the distinctive gestures and poses of each character appearing in the story. In this way Kathak dancers help the audience to follow their storytelling. Indeed Kathak dancers also conduct their musicians on stage, indicating changes in tempo and also unrehearsed repetitions of lines of poetry Performance conventions also allow Kathak dancers to establish eye contact with audience members, and even to speak to them, as demonstrated by an incident during a performance in San Jose, California [3] by my Guru Pandit Birju Maharaj. In the midst of dancing Makan chori (the story of young Krishna stealing the butter), a little child burbled. Without skipping a beat. Maharaji turned toward the direction of the baby's voice and responded into the darkness of the auditorium, "Haan beta? -- yes baby?") The audience burst into laughter, and this human interaction created a link between Maharaji, his story and his audience.

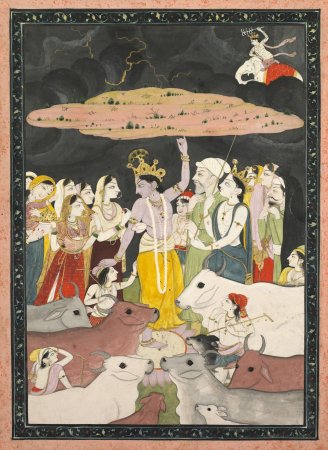

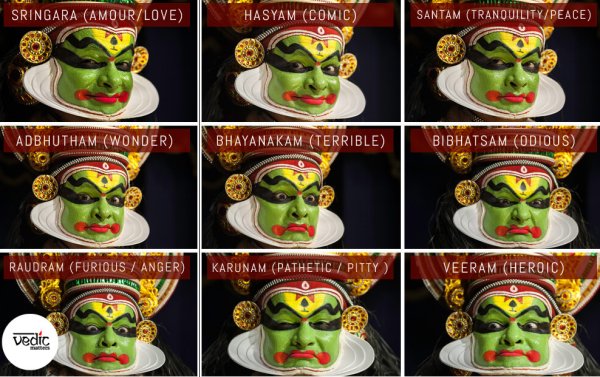

2. PSYCHO-PHYSICAL PREPARATION Understanding the story - creating a sequence of episodes All dancers need to decide what story we want to tell and why we want to tell it, Will it be a simple narration with a straightforward goal - entertaining the audience? Or is there an underlying message we want to convey? We need to decide the length of our performance, and what details we will include. What is the sequence of episodes and how does that affect the story's meaning? In what order will the nature of each character be revealed? For example, in narrating the Sita Haran episode of the Ramayana, at what point will Raavana's true nature be revealed, and what gestures will signal the transformation?  Hori (10.22.06, NYC, 92nd Street "Y", "Sundays @ 3" L to R: Chikako Iwahori, Amiya Dingare, Antara Basu-Zych; kneeling, Anup Kumar Das. Photo © Briana Blasko) I'll give an example of the importance of sequence in character development from my training with Maharaji. I frequently staged the Bindadin Maharaj hori, describing Krishna playing Holi with the gopis - Kanha khelo kahan aisi hori guiyan ("Friend, where would Krishna play Holi like this?" Translation by Anisha & Laxmi Muni). When the dancers performed my choreography for Maharaji, he was displeased. "What is your critique?" I asked Maharaji. [The following is a paraphrase of Maharaji's answer.] "Without fully showing Krishna's pranks and the gopi's [feigned] displeasure, you immediately launched into a scene of the gopis dancing joyfully with Krishna. And so their actions - tying his hands, throwing a bucket of water on him, dressing him in a sari and decorating him with women's jewelry - were not motivated," he said. 3. LANGUAGE of GESTURES - Hasta Mudras During the early years of post-Independence India, when the arts were being revived and codified, a great deal was written and discussed about the "traditional" and "authentic" vocabularies of the various classical Indian dance styles. Some vidwans (scholars) asserted that Kathak dance hand gestures were so vague as to render them almost non-existent, and certainly unclassifiable. Some of the thoughtful practitioners of Kathak disagreed. Discussions and seminars ensued. The eminent Kathak dancer and Guru Maya Rao, a disciple of Guru Shambhu Maharaj, opened her article in the September 1959 issue of MARG Magazine (pp. 44-47) "The Hastas in Kathak" with the following astute observation: "Kathak employs a series of gestures to interpret the varied richness of creation. Yet it does not follow the system of memorizing the hastas as a code under their prescribed names, as we find in Bharata Natyam or Kathakali. In Kathak, the body as a whole is visualized as the prime medium of expression. Hence its gestural language is not classified separately. "For instance, if the dancer intends to represent the moon, not only will his hands show the Ardha-chandra Hasta, but his body will also bend in an arch to suggest the crescent moon."  Chandra Kala mudra (YouTube video by Racingrhythms- Bharatanatyam Mudras)  Neelima Azim performing a ghazal points to the rising crescent moon (Kothari, p 211) This concise description summarizes one of Kathak's distinctive features, which makes characters in storytelling appear less formal, less distant from the ordinary realm of human movement. Rather than manifesting symbols of emotions and objects at the ends of their arms - outside the body's core - Kathak dancers "become" the object or emotion. This statement may be a gross generalization, but it does call attention to a distinct difference between Kathak and more stylized forms of classical Indian dance. 4. FACIAL EXPRESSIONS : Nava Rasa & Hand-eye coordination Trained use of the eyes adds an essential element in improvisation. Eye movements can suggest the movement in empty space of unseen objects such as a bird or a ball. Their consistent focus can fix objects such as the contents of a room - for example the high cupboard in which Yashoda puts her butter pot, which Krishna sees and raids for the butter (in the story Makan chori). Eyes can convey the emotion of the character which the dancer is portraying. Eyes can suggest a character's response to a situation or to other characters in the story.  Kapita mudra (YouTube video by Racingrhythms- Bharatanatyam Mudras) One of my first lessons in the coordination of eye movements, hand gestures and body movements was given when Maharaji demonstrated a bird landing on his wrist, then taking flight and flying off into the distance. His eyes clearly acknowledged the bird - shown by kapiita mudra - alighting on his wrist, then suddenly taking off and flying into the distance. The bird's flight was shown only by the focus of the eyes, from very near to very far. When the bird took flight, a breath was taken and the chest rose, mirroring the bird's upward flight. The eyes' focus, which had been on the bird, changed to a startled fluttering of the eyelashes, followed by a sudden rise in the focus, then a gradual, progressively distant focus. My description of this split-second movement has taken many words, but practicing the movement and depicting it realistically took me many hours. Likewise, in learning to dance the episode of Krishna playing ball in the Kaliya daman story, Maharaji broke down the movements to show the pathway of the ball: look at the ball in the cupped R hand, then slap the R foot and simultaneously flatten the palm as the R hand rises slightly and the fingers straighten in a motion of releasing the ball. This split-second hand action coordinates with the eyes and subsequent hand action. Both the hand and the eyes follow the trajectory of the invisible ball, tracing an arc from R hand to L hand. (youtu.be/WXkNDj0EqXg @ time code 3:34) Instructions in the use of eyes in storytelling often include lessons in the nava rasa theory of aesthetics. Defined as "the nine emotions", the nava rasas include sringaarah (love), viram (valor), raudram (anger), bhibhatsam (disgust), bhayaanakam (fear), haasyam (laughter), kaarunyam (sadness, compassion), adbhutam (surprise, wonder), and shantam (peace).  Balasaraswati in ĎKrishna nee begane' (Marilyn Silverstone, 1970, New Delhi)  Balasaraswati It is essential, in understanding the concept of rasa, to note that rasa is a sentiment or an emotion evoked in each member of the audience. It is not an emotional state which is experienced by the actor him/herself. This is clearly illustrated in the following interchange between the great Bharatanatyam dancer Balasaraswati and an overly enthusiastic audience member. When he gushed to Balasaraswati after a particularly inspired performance, "You must have been lost in your love for baby Krishna", she is purported to have replied, "Never. When I am onstage, I know what I am doing every single moment." Balasaraswati was fully invested in the emotions she was projecting, but not for her own emotional satisfaction. Some gurus teach the nava rasa as a methodical means of introducing students to the range of possibilities in using the face and eyes to reveal a character's emotions. As each episode of the story progresses, a narrator or program notes clearly delineate which rasa is being depicted in each episode. I must admit that I was quite entranced by a Bharatanatyam item danced by Navtej Johar using episodes of the Ramayana as examples of the nava rasa - for example the appearance of Raavana's sister, Surpanakha to evoke bhibhatsam (disgust) and her marriage proposal to Rama to evoke haasyam (laughter/ ridicule). However, when I asked my own guru, Pt. Birju Maharaj, whether the Lucknow Kathak repertoire includes such examples of nava rasa, he responded that we did not have such items. I think he considered those types of items to be exercises, which do not reflect Kathak's naturalistic, less stylized abhinaya. He commented that anyway, our stories include all the rasas - "Look at the story of Govardhan Lila." Maharaji continued by listing each episode in the story and elaborating on the rasa which it exemplifies.  Krishna lifting Mt Govardhan (Kangra painting, 18th century, Cleveland Museum) Lord Indra displays Viram rasa (valor) as he rides through the heavens, and he displays Raudram rasa (anger) when he creates a rain storm, punishing the villagers who are following Lord Krishna's instructions to worship the mountain on which their cattle graze, rather than worshipping Indra (the Vedic god of rain). The villagers exhibit Bhayaanakam rasa (fear) when they are drowning in Indra's rain storm. Lord Krishna manifests Karuna rasa (compassion) when he responds to the villagers' pleas for salvation, and in return the villagers exhibit Adbhuta rasa (wonder), when they see Lord Krishna raising Mount Govardhan on one little finger, like an umbrella to protect them. [4] Bhakti sringaarah rasa (loving worship) as well as Haasyam rasa (laughter/happiness) are depicted when the villagers joyfully worship Krishna as Mt. Govardhan. The story ends with Shanta rasa (peace). The rain storm has abated and Krishna blesses the villagers, and by extension, he blesses the world. "Only Biibhatsam is missing", Maharaji concluded with a satisfied look.

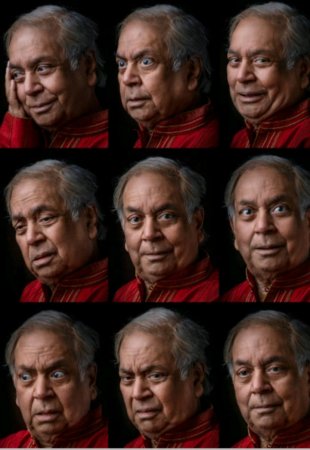

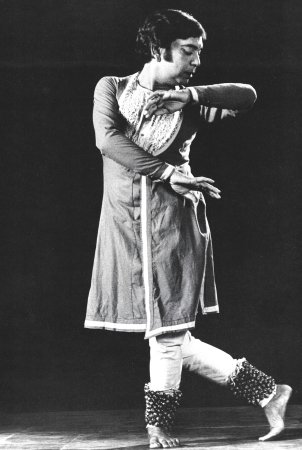

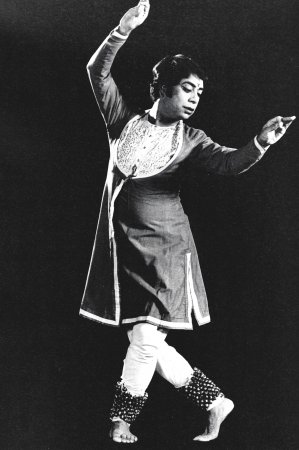

Maharaji continued, listing example after example of the rasas which we students had learned to depict as we increased our vocabulary of stories. Repeating these stories in individual and classroom practice sessions and receiving critiques from our gurus and classmates, Kathak dancers build a vocabulary of facial expressions and learn to depict them according to believable motivation, not dictated by a navarasa checklist.  Birju Maharaj, nava rasa (posted by Anindita Sen) It is interesting that later in his life, Pt. Birju Maharaj was photographed illustrating the nine rasas, from which a systematic chart was compiled. His grandson Tribhuwan Maharaj has created a YouTube video which introduces the concept of Nava Rasa through an approach similar to that used in Navtej Johar's Bharata Natyam item. Entitled "Kathak Natyam - Nava Rasa - A perspective based approach", the video is composed of short skits depicting each rasa, danced by Tribhuwan, his wife the Bharatanatyam dancer Rajni Adhikari, his mother the eminent Kathak Guru Ruby Mishra, and the Bharatanatyam dancer Karuna Singla.  Kathakali nava rasas (Vedic Matters) Many of the other Indian classical dance styles use the concept of Nava Rasa as a means of studying the building blocks for embodiment and improvisation, as is evident from this chart illustrating Nava Rasa in Kathakali abhinaya. And the concept has become so familiar internationally, that the November 2020 TIME MAGAZINE cover story "The Science of Emotions" was illustrated with its own abbreviated nava rasa chart.  Time magazine, 2020 5. BREATH CONTROL - Stamina and animation of the face In my experience there was not training in breath control. Especially in view of the connection of dance with meditation and spirituality, there is need for further study and training. Bol parhant - recitation of the language of the tabla and pakhawaj drums - is an essential aspect of a Kathak performance. A dancer proves her mastery of the nritta / rhythmic repertoire by reciting rhythmic compositions so that they fall within the chosen time cycle. A breathless recitation distracts from the beauty of the otherwise glorious sounds of tabla and pakhawaj drum syllables, and it is ineffective in exhibiting the beauty and strength of precision. Breath animates the face, whether with flaring nostrils and widened eyes to indicate extreme anger; deep breaths to expand the chest and magnify the stature of a hero or demon; shallow breaths to deflate the chest and to diminish a character's size; sudden inhalation to indicate astonishment or fear. The list continues. 6. MOVEMENT THROUGH SPACE & USE OF EYES - Gat nikas & Gat bhav One of the most valuable Kathak dance techniques - which both trains the student for storytelling and is an integral part of performances -- is named GAT, a word derived from the Sanskrit gam, meaning "to go". Used in the Hindi vocabulary for Kathak terms, the word gat means "gait or walk". Kathak dancers are first introduced to gat as GAT NIKAS, a short movement phrase including a pose and a walk, which carries this pose through space. The word nikas, meaning "to emerge, to come out", is derived from Pharsi, the Persian / Iranian language. The hybrid Sanskrit-Pharsi origins of the name Gat-Nikas indicate the syncretic Hindu-Islamic origins not only of this specific term, but also of Kathak itself. The underlying rationale for the gat nikas storytelling technique acknowledges the unique way all creatures move - their gat, their gait. For example, each of us exhibits such a distinctive manner of moving, that an acquaintance walking away from us in the distance can be easily identified not by her face, which is turned away from us, but by her distinctive walk and posture. Based on this observation of movement in the world we inhabit, the Kathak dancer learns to build characters, setting in motion the human, divine and animal players who interact in a story. A Kathak dancer builds a visual memory bank of human movement and physical details of people and objects.  Pt Birju Maharaj (palta) Photo: Avinash Pasricha  Janaki Patrik (palta) Photo: Grace Sutton Each gat nikas follows a specific pattern. In the first four beats of a medium speed 8-beat phrase, the dancer turns quickly clockwise, then counter-clockwise and then assumes a motionless pose, in which neither body nor eyes move. This distinctive pair of turns is named palta, from the verb palatna, to turn over. The photo above shows Pt. Birju Maharaj spiraling counter-clockwise in preparation for the first half of the palta , which unspirals into a clockwise turn. The next photo shows Janaki Patrik at the height of the clockwise turn.  Pt Birju Maharaj (thaat) Photo: Avinash Pasricha  Shambhavi Dandekar (Rukhsaar gat nikas) These two split second clockwise-counterclockwise turns -- like the snapping open-shut, open-shut of a fan - dramatize the introduction of a gat nikas pose. A wide range of poses are exhibited in gat nikas, including abstract, decorative poses such as thaat (shown by Pt. Birju Maharaj) and rukhsaar (a word meaning "face or countenance or cheek"), shown by Shambhavi Dandekar. Three other gat nikas poses from the Moghul-inspired Kathak vocabulary are shown by Pt. Birju Maharaj.  Pt Birju Maharaj (gat nikas) Photo: Avinash Pasricha  Pt Birju Maharaj (bansuri ka gat) Poses depicting objects associated with mythological characters and deities, such as Lord Krishna holding a flute, create a "visual shorthand" which can establish characters and moods in a split second. Pt. Birju Maharaj is shown above in the gat nikas pose named bansuri or murli, which establishes his identity as Krishna whose most iconic pose shows him playing the flute. The origin of many gat nikas poses in real objects and everyday human gestures is demonstrated in the photo which shows Pt. Birju Maharaj playing areal bansuri in a class at Kathak Kendra. Learning panghat gat nikas was a lesson in obeying the physical laws of nature to create a believable "artificial reality". You can't tilt your head gracefully or look up to avoid an overhanging branch. Gravity will make the earthen waterpot fall off your head!  Birju Maharaj playing the flute  Saswati Sen doing panghat gat nikas A video from India's national public television archive, Doordarshan's Prasar Bharati Archives, is posted on YouTube and listed as Class 16 - Gat Nikas in the series "Learn Kathak with Pandit Birju Maharaj". In this video, Pt. Birju Maharaj and his disciples demonstrate several Gat Nikas. Each starts with a palta, which leads into fast forward stepping, accompanied by a 4-beat phrase of distinctive tabla bols:  These typical tabla bols stop abruptly mid-aavartan - on the 4th beat - and the dancer assumes a "freeze-pose". That is, the tabla does not play and the dancer does not move during the last four beats of this aavartan. [5 ]This completely motionless and soundless pause dramatically emphasizes the emergence --the NIKAS - of the character or object or activity (from the verb nikalna, meaning "to emerge). Moreover, the motionless pose gives the audience time to register which character will be taking over the action in the next sequence. The poses shown include Thaat @ Time code 1:18 & 2:28, Parvati @ 3:52, Talvaar (sword) @ 6:28, Flute / Krishna @ 7:20, Ghunghat (5 ways to grasp a veil and 5 different expressions) @ 8:40, Nau (rowing a boat) @ 10:40, Sanp (snake) @ 14:01, Anchal (ornamented end of a sari, typically displayed by draping it over the shoulder @ 13:00, Mor (peacock) @ 14:20.

Pt. Birju Maharaj shows an example of the murli (flute) gat nikas in an excerpt from this same video @ Time code 7:10. Maharaji's hands show the position for playing a flute, thus identifying that he is enacting Lord Krishna. Maharaji then enlivens the pose, walking with a cocky self-confidence which reflects Krishna's natkhat, mischief-making nature. This example demonstrates that the gat nikas technique gives a Kathak dancer the necessary practice in quickly establishing characters or activities, which is essential in improvisation. In the typical structure of a gat, freezing in a pose is followed by a walk, often indicative of the character or animal's nature, as noted in the video example above. A typical CHAAL (walk) accompanied on the tabla playing the bols Na dhin dhin na, is used to move the character through space, while the torso positions and facial expressions help to establish the internal nature of the character. The gat concludes with a second set of palta turns - clockwise and counterclockwise, and then a retreat step in quadruple time holding the pose and moving backward on a diagonal. The archetypal walks included in the typical structure of a gat, as well as the single, double and quadruple tempi of the walks, train a Kathak student in the techniques of moving on the stage and varying the tempi of the presentation. When these various poses and walks are strung together, a storyline is established, and this more extended depiction is called a GAT BHAV [6], as in this example of Pt. Birju Maharaj showing a mahout riding on an elephant- both the elephant and the human rider. The beginning of this wordless story is often introduced by the distinctive palta - clockwise and counterclockwise turns (time code 0:05). Another example of gat bhav, which combines gestures representing the natural world (clouds) as well as animals (peacock) is seen in Maharaji's performance of the mor ka gat bhav . The "rolling" of Maharaji's upper chest, and the control of breath indicated by this movement, are integral to the depiction of the puffed-out chest of a bird.

The final example of gat bhav which I have included is an extended story exemplifying the creation of both characters and objects. In this episode, Pt. Birju Maharaj performs a signature item in his repertoire - makan chori gat bhav. It depicts the very young Krishna stealing butter, which his mother Yashoda has just churned. Maharaji performed this gat bhav hundreds - perhaps thousands - of times throughout his long performance career (b. 4 February 1938, d. 16 January 2022). It is instructive to compare an early version which Maharaji performed in his youth, with one performed in his mature years - on 27th October 2009 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. 7. ENERGY - DYNAMICS - Tatkaar In my Narthaki essay on UPAJ - Part 1- NRITTA, I discussed tatkaar improvisation as a technique of pure dance - nritta. But a Kathak dancer's command of speed, nuanced sound and rhythmic variation in tatkaar is much more than pure rhythmic play. It is also an essential aspect of storytelling. During the long process of training and practice, a Kathak dancer learns by rote the choreography for a large repertoire of stories and story poems, each with its distinctive stepping patterns associated with characters, objects, moods and natural phenomena. This "sound-painting" - amplified by bells worn around both ankles --suggests specific rhythms and sounds of the human and natural world. Eventually, learning exact stepping patterns for a repertoire of stories provides a dancer with an extensive vocabulary of tatkaar "sound-painting" patterns, which can be used to depict elements of stories, other than those stories in which the sounds were originally used.  Simhamukhaha mudra (YouTube video by Racingrhythms-Bharatanatyam mudras)  Kartarimukhaha mudra (YouTube video by Racingrhythms-Bharatanatyam mudras) Our footwork accompanies the gestures of the story - for example, the soft patter of raindrops - shown by simhamukhaha mudra with both hands gently shaking downward in front of the face - is accompanied by a soft shimmer of fast tatkaar, which gradually slows down as the rain abates, until only a few gentle taps on the ball of one foot signal that the rain is stopping. The cutting, downward, zig-zag diagonal of lightning, shown with fingers in kartarimukhaha mudra - is accompanied by a fast percussive phrase - tig dha dig dig thei - performed on the side of one foot and heel beat of the other foot. Slowly a vocabulary of footwork patterns link sounds and stepping patterns with elements of storytelling. The full effect of this combination is displayed in the Kathak genre Gat Bhav as has been shown in the YouTube sequences cited above. 8. Supporting musicians This essay would be incomplete without mentioning the vital role played by accompanying musicians. Building relationships -- rehearsing and performing with the same accompanying musicians over a period of many years -- creates a treasure chest of shared repertoire. Whether the knowledge shared is poetic texts or the choice of episodes in a particular story, musicians who accompany a dancer repeatedly will understand the mood and message we are conveying in our stories, thereby helping us to illuminate our interpretations. Supportive accompanists are not reading notation. They are intently watching our every move. This intense concentration on the moment-by-moment changes in our body and facial movements ensures that the raga and tala will change according to our momentís inspiration. No doubt simple communication with accompanying musicians is achieved when the dancer looks pointedly at them and gestures with palm waving up or down to indicate "raise the tempo" or "lower the tempo". Looking at them with a single strong nod of the head and extending a closed fist indicates that we want the musicians to hold the tempo steady. But in addition to these intuitively-understood gestures, the dancer and musicians will have discussed the poetry or story before the performance. Or perhaps they will not need to discuss, because they have performed the same story many times or have heard this version from their grandmothers. Maybe they just need to discuss a few details for one minute. For example, what kind of audience is this, and what length and in what detail will the dancer tell the story? Should each verse be repeated a specified number of times, or will the performer step to the microphone and sing (or recite) the next verse to indicate that s/he is ready to move on to the next verse/episode? Or will the dancer simply gesture with a circular wave of the right hand to indicate "move on"? Or perhaps the musicians have performed with this dancer so many times that they know the gestures or glances through which s/he communicates with them. The fact is that successful storytelling improvisations are usually built on long-term relationships, often extending over many years and many shared stories. The accompanists may have played for the dancer's classes when s/he learned this item from the guru, or the musicians may have accompanied the sessions during which the dancer created the choreography for a particular story. Moreover, in the case of "biradiri" -- Kathak family clan members -- relationships may extend through the bloodlines of generations. When I first met Maharaji, his principle tabla accompanist for performances was Manika Prasad Misra, and his accompanist for daily classes was Viswanath Misra. Both were Maharajiís close relatives. My experience is of course with my Guru, the late Pandit Birju Maharaj, with whom my relationship started with my first classes in 1967. My relationship was essentially as an informed outsider. But that means, for example, that I learned that Maharaji is a Vaishnav. Vishnu preserves - he does not kill. Maharaji's version of the story of the serpent Kaliya is therefore a Vaishnav interpretation. Maharaji is a Krishna bhakt, and as such, he teaches Kaliya Daman (The Control of Kaliya), not Kaliya Mardana (The Killing of Kaliya). The accompanying raga and final tabla strokes for the footwork will convey victorious control and an overarching protective love of all creation. The sarangiís melody will linger in the air and float in a musical sound suggesting peace. All this in a 3 or 4 minute gat bhav Ė an item without words. The dancer and accompanying musicians join in a shared interpretation of a known story. I may dance Maharajiís version of the story, and the musicians may play the same story in their accompaniment. But we add our own emotional and intellectual interpretations, making the story more or less believable, and more or less emotionally moving, but never an exact carbon copy of someone else's version of the story. With accompanists who watch intently and know the story, or follow the poetry which is being sung, it is hardly relevant whether the dancer moves to the back of the stage or to the front, whether the same phrase of poetry is interpreted one or ten times, whether the serpent Kaliya is shown with his wives begging Krishna not to kill him, or whether this detail is omitted. The accompanists are watching. They are also telling the story -- with the intensity or delicacy or in-your-face virtuosity or restrained quiet of their strokes and melodic embroidery. They have an immense vocabulary of rhythmic and melodic techniques to support the common goal of telling the story with the dancer. UPAJ - A few concluding thoughts Improvisation is not magic. On the contrary it is the result of an artist's thousands of hours of training, individual practice, performing, and also listening to and watching other artistes' rehearsals and performances. An artiste creates a deep reserve of techniques, stories and ideas, which can be called on almost subconsciously and seemingly without any preparation. I like the definition of "improvisation" given by my colleague, the Bharatanatyam dancer Aditi Dhruv, as "an organic, spontaneous thing that happens before (or after) thought." This definition acknowledges that there is indeed pre-meditation -- "thought" -- in the process. The illusion of improvisation as "extempore" - literally "out of the moment" (Latin) -- conceals the truth of its thoughtful, lengthy and rigorous preparation. This essay has detailed some of the elements which a trained Kathak dancer draws on to create that seemingly "extempore" improvisation - "in the moment" drawing the audience into the story - the KATHA of KATHAK. NOTES

Trained in both classical Kathak dance (Pt. Birju Maharaj, beginning 1967) and Merce Cunningham modern dance technique (1971 to 1978), Janaki Patrik has choreographed thirty full-evening productions and numerous shorter works exploring an eclectic range of poetry, mythic storytelling and music. She is the Artistic Director and Founder (1978) of The Kathak Ensemble & Friends/CARAVAN, NYC. A dedicated teacher, Janaki has trained dancers to perform an extensive repertoire of classical Kathak, as well as her new choreography. Teaching and performing in inner-city schools through Urban Gateways / Chicago and Young Audiences / New York for forty years, Janaki has embodied the power of dance and music to communicate the interconnections of all cultures. Post your comments Please provide your name along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |