|   |

|   |

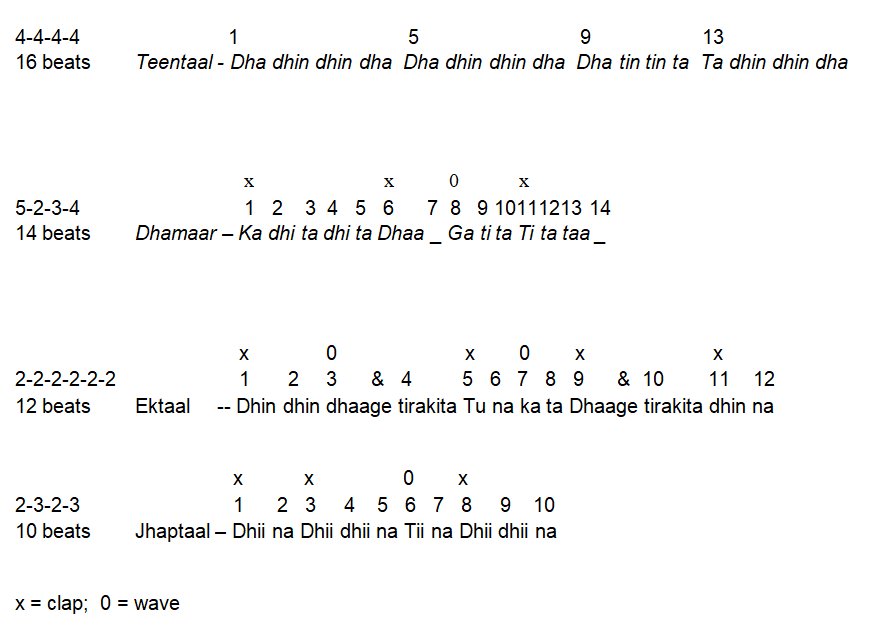

e-mail: janakipatrik@gmail.com UPAJ - Improvisation in Kathak September 16, 2020 Classical north Indian Kathak dance has been my life's work. Having studied since 1967 during extended periods with India's pre-eminent Kathak dancer and guru Pt. Birju Maharaj, I have witnessed many of his solo performances, given many performances of my own and seen many performances by other Kathak artistes. Over the more than 50-year period of my life as a Kathak artiste, I've also had a chance to analyze the components of this great classical dance tradition. Improvisation is one of those components which has fascinated me since I first saw Pt. Birju Maharaj perform in 1963 and was mesmerized. His performance did not appear to be composed. It appeared to be effortlessly improvised. When I decided in that moment to become a Kathak dancer, I wanted to learn everything, and especially improvisation. My husband is a jazz trumpet player, and improvisation is the heartbeat of jazz. Classes in improvisation are taught in all music schools which teach jazz and have jazz ensembles. But I was not taught improvisation in my Kathak training, though improvisation is considered a core part of a solo Kathak dance performance. Where Kathak improvisation comes from is often described in semi-mystical terms. Some people say that it's a spontaneous act that happens before or after thought -- that improvisation is a gift - that it can't be learned - that you either have it or you don't.  Janaki Patrik (Photo: Briana Blasko) I don't agree with this concept. The word "spontaneous" may be the culprit in misconceptions about improvisation, implying that improvisations appear out of thin air. On the contrary, Kathak dancers create the illusion of spontaneity by using well-practiced and calculated techniques, while accompanied by musicians who also have spent years preparing to accompany whatever compositions the dancer may present. The illusion of spontaneity is buttressed by thousands of hours of nritta practice (footwork and "pure", non-narrative dance compositions); by thousands of hours learning from our Gurus how to illuminate poetry and tell stories in movement - nritya; by thousands of hours reciting the drum syllables of rhythmic compositions - bol parhant; by thousands of hours spent listening to our Gurus speak about their interpretations of poems and stories, and why they choose certain movements and facial expressions. In this essay, I have identified five elements of improvisation and shown them to be concrete techniques of our craft, rather than some elusive source of quasi-mystical inspiration. YouTube videos linked to this article illustrate these elements -- bol parhant, lehra, theka, tihai and jugalbandhi. A sixth element - trained musicians - depends mostly on relationships nurtured over time with musicians who know our art and inject precision combined with emotional sensitivity. To reduce the wordy-ness of an already lengthy essay, I moved some of the detailed information about the examples from the body of the essay into the "Description" section of those YouTube videos. When you click on the YouTube links, the video and its "thumbnail" photo appear on the screen. But for added information - about the performer pictured, or about the situation in which I collected that music, or about the notation of the compositions - you can scroll down, read the first two lines of the Description and then click on READ MORE. In this way you have a choice about how much time you devote to reading this article, and how much detail you want to take with you. I have divided this essay into two sections: NRITTA - Non-narrative, "pure dance" improvisations and NRITYA - Storytelling in Poetry Improvisations. At the end of the essay I give a few of my thoughts about 'What makes an improvisation great.' NRITTA - Non-narrative, "pure dance" improvisations Lehra and theka create an audible framework for improvisation. We hear, we do not think the rhythmic structures, which lehra and theka delineate and within which we improvise. Not having to think about the time frame, our minds are free to access the rhythmic and movement phrases which we have practiced and stored in our kinesthetic memories. Tihai and jugalbandhi are two devices in Hindustani music and dance, which we use to generate improvisations and help audiences to follow them. These four fundamental techniques are supported in turn by the powerful tool of bol parhant, and by the absolutely essential support of gifted musicians, who not only accompany our dance, but also feed us ideas and create the soundscape against which our dance glows. Below I have discussed these elements of improvisation. I have included video excerpts and voice recordings so that readers can see and hear why these elements are important. The definitions and examples are meant to help those unfamiliar with Hindustani music and dance to understand some of the basic structures of Kathak dance by seeing and hearing them. Connoisseurs and practitioners of Kathak may also be reminded of what we take for granted and overlook as we study the roots of improvisation. 1. BOL PARHANT: Recitation of the drum / dance language which preserves the compositions of our repertoire. (from bol = a syllable in drum / dance language, from the verb bolna- to speak + parhant / padhant = recitation, from the verb parhana / padhana - to speak, to recite) Bol parhant is the language of dance and drum syllables (bols) recited by Kathak dancers and Hindustani drummers. This technique provides an unwritten notation system used in the oral transmission of Kathak and tabla compositions. Kathak dancers learn movements and compositions in tandem with bol parhant. Tabla drummers learn the strokes and compositions of their instrument in tandem with this same unwritten language. Consequently Kathak dancers and tabla drummers share a vast memory bank of compositions. While it is true that some bols are specific to Kathak, well-trained drummers can learn these compositions very quickly, if they want to do so. There are also vocalists, like my Hindustani vocal Guru, Sri Samarth Nagarkar-ji, who have memorized a large repertoire of Kathak compositions, simply because they are attracted to their beauty. It is not miraculous, then, that Kathak dancers and tabla drummers and vocalists can perform together without previously having met or rehearsed. We have received our training by means of this language.  Samarth Nagarkar The beauty and rhythmic complexity of bol parhant is like mind candy to us. When I've learned a new composition, its beauty engages my mind, and I recite it endlessly. Even while walking down the street or pedaling my bicycle, the rhythm of the bols keeps time with my footsteps or the rotation of my bicycle wheels. Here's an example: The first time I met my dance partner, the late Anup Kumar Das, I picked him up at a subway stop, and we drove to a school performance in New Jersey. During the one-hour ride to the school, Anup-ji, tabla drummer Paul Leake and I recited the bols of the compositions we would perform. When we arrived at the school, we all got on stage and performed as if we'd been practicing together for years. This is the power of bol parthant! In the following video youtu.be/fivgWEOpIsw, Samarth Nagarkar recites a composition whose bols are Tha va thun ga. You will also hear me discussing the composition with him, asking Shri Nagarkar whether its phrasing is in Chatusra jati (phrases in multiples of 4's) or in Misra jati (phrases in multiples of 7). A system which demands memorization of a large spoken repertoire trains the brain to identify little phrases and use them to catch hold of more new phrases, though they are assembled in different patterns. After all, this is how we humans learn language - phrase by phrase in endless variations, until our ears recognize them and learn to speak them in our own multiple variations. It's just that in the case of the Kathak and tabla language, the words in the phrases don't consist of "See Geeta run". Instead, we speak the language of bol parhant, and we say Ti ta ka ta ga di gi na Dha or Dig dha dig dig Dig dha dig dig Thei! When creating a new composition, my inner eye sees movements, and my inner ear "translates" them into dance bols. I move these dance bols around until they fit the time frame and combine to make a satisfying composition. The more fluid my bol parhant becomes, the more choices I have for movement and rhythm composition. Bol parhant is therefore an integral part of my choreographic process.  Pt Birju Maharaj In the following video excerpt youtu.be/Phkp_A91Y2g, Pt. Birju Maharaj speaks to the audience, explaining that the same dance language (bhasha) he recites is also played on the tabla. He continues by explaining that his dance words (shabdon) are poetry (kavita and kavya), whereas the ordinary language we speak is not poetry - it is Hindi. He then recites a composition - an Uthan, a category of compositions which open a program - a sort of "curtain raiser" from the verb Uthna - "to rise up". The bols of this Uthan are: Dig ga Dig ga Thei _ Ta thei _ Ta thei. While Maharaj-ji is reciting, the tabla drummer plays simple tabla bols (tabla syllables/sounds), which mark each beat of the 16-beat time cycle. But when Maharaj-ji subsequently dances the same composition, the tabla drummer accompanies by playing exactly the same dance bols (dance words). This demonstration of bol parhant is elegantly simple, and the subsequent dancing is breathtaking. 2. LEHRA: lehra - a repeating melody, each repeat marking one complete cycle of the taal. (lehra is a Sanskrit word meaning "wave"; used interchangeably with the Persian word naghma, meaning "melody") Like a wave in the ocean, the lehra is cyclical. To fulfill its role as time-keeper, its repetitive melody must always start at beat #1 - named sam. The lehra then proceeds melodically through one complete time cycle, called an aavartan, and it returns to sam --- only to start all over again. The lehra is our time-keeper. Dancers and instrumentalists do not mechanically count - we don't need to. The melody of a lehra tells us when we reach the important divisions of the taal - a cycle of a specified number of beats (matras). We hear the counts; we do NOT think the counts. For example, the lehra played by the sarangi in this YouTube music video keeps time in a 16-beat time cycle named teentaal (youtube.com/watch?v=57kNXy4Mxs4). One note is played for each beat. The last four beats of the cycle (counts 13-14-15-16) are indicated by an ascending progression of notes ending on SAM - like climbing up a staircase and arriving home - on the first beat of the time cycle. This YouTube video continues for one hour, since it is designed for Hindustani vocal and Kathak practice. But for purposes of illustrating a lehra / naghma, you may want to listen for only a minute or two. Starting from the first day of our Kathak training, we practice compositions in various rhythmic cycles, accompanied by endless repetitions of the appropriate lehra. The accompanying musicians - whether playing sarangi, harmonium, sitar or sarod - play distinct lehras for each different taal. These melodies become imprinted in our brains, accompanying Kathak dancers throughout our dance lives - on stage, in the classroom, and for our daily practice called riyaaz. We hear the rhythmic signposts of a lehra, and we stay steadily on the rhythmic path.  Mohammed Jan (Photo: Janaki Patrik) Compare the 16-beat teentaal lehra you just heard with the lehra for the 14-beat time cycle named DHAMAAR, played by sarangiya Mohammed Jan (youtu.be/2mhJzkmu4c4) and then compare both the Teentaal (16 beats) and Dhamaar (14 beats) lehras you have just heard with this Jhaptaal (10 beats) lehra, which my guru behin Rani Khanam shared with me (youtu.be/KDbBZNKqxvE).  Rani Khanam (Photo: Prasad Siddhanthi) I hope that this comparison will help you hear how very distinct each lehra is, no matter in what raag it is played. We hear the distinct structure of lehra in various taals, and this helps us to keep track of the rhythmic structure without devoting conscious thought to time-keeping, no matter in what taal we are dancing. 3. THEKA: In Hindustani music, a theka is the unique combinations of drum strokes marking the important divisions for each different taal; the basic rhythmic phrase of a particular taal. (theka in Hindi= support or prop) Typically played on the tabla drum, the theka for each taal consists of a distinctly different set of bols / drum syllables. You've just heard Rani Khanam reciting the theka of Jhaptaal. Below I've written the thekas of several different taals. Speak these thekas aloud, and you'll hear how uniquely different each theka will sound. These unique combinations of drum strokes mark the important divisions for each different taal. Don't be intimidated by the dizzying variety of divisions of these taals; we don't count them while we dance. We hear the divisions, which are indicated by the theka. The sound of the theka as it is played on the tabla tells us exactly where we are in that time cycle. Likewise, the sound of each distinct lehra tells us exactly where we are in a time cycle. Melody and drum bols guide us. Lehra and theka work together, helping Kathak dancers to keep track of the time cycle in which we are dancing, without the need to count or consciously think about where we are in that rhythmic cycle. Our mental energy can be devoted to improvising, not counting! To help you hear each distinct theka, I have spoken the thekas of each of the following taals in this YouTube video (youtu.be/YrXloVKr6N4)  In the classroom - and sometimes even on stage - we speak compositions (bol parhant), and at the same time we use a system of claps and waves of the hands to indicate the divisions of the taal. Clapping and reciting a composition, especially in a complex taal like Dhamaar, is a bit like the childhood challenge of patting the top of our heads and rubbing our stomachs in circles. But it is this concentration on physical and mental coordination that solidifies our memory of the composition.  Sandip Mallick (Photo: Vandana Uttamchand) An example of bol parhant together with claps and waves is shown in this video youtu.be/zX6z5D6go74. Guru Sandip Mallick is seen reciting one of the compositions he has been teaching. His May 2018 workshop, arranged in New York City by The Kathak Ensemble & Friends, included a kavita torah. Its poetry is recited in a medium fast, 16-beat teentaal, whose rhythmic drive sounds a bit like American "rap". His claps and waves are delineating the structure of the taal. 4. TIHAI: A rhythmic phrase which is repeated three times. A tihai can start from any beat in a rhythmic cycle, but it invariably ends on the first beat of the cycle - the sam. It can take one or multiple cycles to repeat three times and return home to sam. Kathak students practice simple tihais starting from the first day of our training. We gradually progress by learning longer and longer tihais, extending two, three, four or even five cycles of whatever taal we are practicing. Improvisational skill is developed when we repeatedly practice many tihai in each taal. We begin to hear the count where the second and third sections of a tihai begin in each taal. Using this innate sense, we can make our own tihais. We practice creating tihai from any beat of the time cycle, a skill which is essential in improvisation. In this YouTube video (youtu.be/5vN0i8gteKU), I have recited a simple tihai and its jora - its longer twin. This longer tihai is based on the core phrase of its shorter twin. In the "Description" box of the YouTube video, I have notated both the short and long tihai. But listening is the best way for you to understand how one tihai can generate another. Tihai may seem to be elaborate mathematical equations, and in a certain sense they are. When dancers and their accompanying tabla drummers finish together on sam, they share an exhilarating sense of success with the audience, as if a mathematical equation has been solved. But there's a difference. We don't write our tihais on a blackboard. We dance them in space. We hear them in our minds. We speak them in drum syllables. And we have PERFORMED the beginning phrases of the "equation" so that audience members are initiated into our "mathematical game", and they SEE the game being played. The tihai is one of Kathak's most powerful improvisational tools. Performing a tihai and returning to the first beat of the time cycle helps to build a "dynamic of inevitability". This is very exciting for the audience members, who feel as if they are insiders in the rhythmic game. They hear the footwork pattern in the first part of the tihai, then they recognize the second repeat, and finally they anticipate the third repeat, which ends on sam. The simplest tihais can be the most effective - for example those built on multiples of 3's. Listen to the tihais included in the opening minutes of Pt. Birju Maharaj's Upaj at the Uttar Pradesh Sangeet Natak Akademi's Rajat Jayantii Samaaroh in Lucknow on 12 November 1988 (youtu.be/dz5ZgOEFn58). The tihai performed from 0:58 to 1:03 starts from the 11th beat, continuing with 9 evenly-spaced foot slaps, performed with mathematical precision - 3 sets of 3, the last slap - the 9th - ending on sam. This tihai satisfies the audience, because its structure is transparent. It leads into two more elegantly simple tihai - 1:14 to 1:18, followed by the simplest of all - 3 slaps, the 3rd ending on sam - 1:47 to 1:48. This video file cuts off the last one minute twenty seconds of Maharaj's upaj. I have included this breathtaking upaj, because the movement and sound are in sync. You can see the entire Upaj in the YouTube link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RKhql... , but in that YouTube video the transmission of the same upaj is faulty. The sound and movement are out of sync by a split-second. 5. JUGALBANDHI - A duet between various configurations of artistes - Kathak and tabla, two Kathak dancers, tabla and instrumentalist, two vocalists, two instrumentalists. (Jugal=pair, twins; bhandhi=bound together, entwined. Also called Sawal-Jawab (Sawal=question, Jawab=answer) Whether called Jugalbandhi or Sawall-Jawab, this technique is a popular improvisational form. Audiences quickly understand the game and can follow the friendly challenge. One of the two artistes leads by creating a rhythmic phrase, and the other must answer with the same rhythmic phrase. Starting from our first days in the classroom, Kathak dancers learn the format, practicing examples in pre-made patterns. We learn that the initial phrase is typically long - one or two avartan in length. The phrases become progressively shorter, until the two members of the challenge are playing back to back, as if shouting questions and answers back and forth to each other, until they end together with a final, resounding DHA on sam. The jugalbandhi / sawal jawab format is a sure-fire way to end an improvisation with excitement, as is evident in this Jugalbandhi (youtu.be/5fTTtH1CFxY) between Pt. Birju Maharaj and a tabla guru who was teaching at Lucknow's Bhatknande College, Lucknow, at the time of this performance. I will continue this article with Part 2, in which I discuss the Kathak techniques which contribute to fluidity in NRITYA Improvisation - the Kathak art of story-telling. The article will conclude with a few thoughts and YouTube exhibits focused on 'What makes an improvisation great.' (c) Janaki Patrik, Founder & Artistic Director, Kathak Ensemble & Friends, NYC and Narthaki Online, 16 September 2020 GLOSSARY - aavartan - one complete cycle of a taal - bol - a sound or syllable in Hindustani music and dance language; from the verb "bolna" - to speak - bol parhant - recitation of the drum-and-dance syllables which accompany Kathak dance compositions. Bols verbalize the sounds of the drum and the dance compositions. Bol parhant is a brilliant system for preserving Hindustani dance and drum compositions, which are transmitted orally, rather than by a system of written notation. - khaalii - "empty" beat, generally a beat in the time cycle on which the baayan (lower drum in a pair of tabla) is not played. - laya - tempo; vilambit laya-slow tempo, madhya laya-medium tempo, drut laya-fast tempo - lehra - Sanskrit word meaning "wave"; used interchangeably with the term naghma, a Persian word meaning "melody". The lehra is a melody which fills exactly one avartan of any taal. It repeats over and over in order to demarcate the boundaries - the beginnings and endings of each cycle. - mandra saptak - the lower octave in vocal or instrumental range - maatra - one beat - raga - a tonal framework for composition and improvisation (definition by Joep Bor); a progression of pitches, somewhat approximating a Western "scale" - riyaaz - practice - sam - the downbeat / first beat of a time cycle - saptak - octave - sargam - Sa-Re-Ga-Ma - the pitches of a raga, approximating the "notes" of a western scale - swar - a single note in a raga - taal - time cycle, each having a specified number of beats, for example, teentaal (16 beats), taal ashtamangal (15 beats), taal dhamaar (14 beats), ektaal (12 beats), jhaptaal (10 beats), taal rupak (7 beats) - tatkaar - footwork; rhythmic patterns made by slapping the bare feet - theka - the distinctive set of drum bols delineating the divisions within a single aavartan of a particular taal  Trained in both classical Kathak dance (Pt. Birju Maharaj, beginning 1967) and Merce Cunningham modern dance technique (1971 to 1978), Janaki Patrik has choreographed thirty full-evening productions and numerous shorter works exploring an eclectic range of poetry, mythic storytelling and music. She is the Artistic Director and Founder (1978) of The Kathak Ensemble & Friends/CARAVAN, NYC. A dedicated teacher, Janaki has trained dancers to perform an extensive repertoire of classical Kathak, as well as her new choreography. Teaching and performing in inner-city schools through Urban Gateways/Chicago and Young Audiences/New York for forty years, Janaki has embodied the power of dance and music to communicate the interconnections of all cultures. Responses * Pranam Janaki ji, Reading this brings the memories of sitting at your feet while learning to recite the Bol Paranth. So true... The language of dance and music is like any language, the more one practices the more fluent one gets. Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts and the videos. - Jyoti Nath Yelagalawadi (Feb 4, 2024) * Dear Janaki, I just read part one of your article on improvisation in Kathak dance. I think it’s exceptional! Perfect! You are revealing in an easy to understand language the mechanisms of improvisation. Each facet of music and dance which you aptly explore and explain, is an “inside look” into the deep realizations of spontaneous artistic liberation. There are rules of course, in raga and tala, like forbidden notes or too few or too many beats… but the artist is committed to exceeding traditional conventions by creating something totally new. It is a spur of the moment decision! What I think you so perfectly make clear, are the advantages of “training to improvise”, by listening to and internally memorizing the melodies and time signatures. My tabla teacher Ustad Keramat Khan always said - “Decide on an Uthan (opening piece), decide on a final tehai…The rest you can improvise!” Could it be that even spontenaity has a beginning and an end? Thanks so very much for your important research and lucid sharing! Can’t wait to read part two! - Paul Leake (aka Tabla Paul) (December 30, 2023) * It's a beautiful read, Janakiji. It's so content rich and deep in your experiences and interpretations, that just by reading this column I felt that I attended a fantastic Kathak lecture demonstration. Thank you for this gift and my regards. - Jayeeta Dutta (Sept 19, 2020) Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |