|   |

|   |

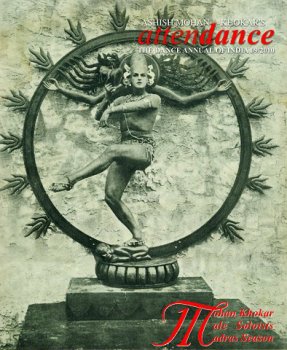

The role and contribution of pioneering gurus and foreigners in the revival of classical Indian dances (1900s-50s) - Ashish Mohan Khokar, Bangalore e-mail: mr.dancehistory@gmail.com February 8, 2011 (This article was first featured in the Natya Kala Conference 2010 souvenir.) Victor Dandre, in 1922, on a visit to India, lamented, "There are no schools of dancing in India and it is an art which nobody is interested in." All he and his wife, the famed Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, got to see in this visit, that too in the first capital of India – Calcutta- was some variety of Nautch dances. Anna Pavlova became a catalyst for encouraging two of India's biggest dance names, Uday Shankar and Rukmini Devi. In India, Pavlova had occasion to attend a wedding, and now her attention turned to producing a ballet on this. A leading dancer with her, Harcourt Algeranoff was directed to pore over books and visuals to cull ideas for the wedding ceremonies, costumes and setting and next, a musician was to be found and the choice fell on a certain Bengali lass settled in London, Coomalata Banerjee. She was auditioned and hired to do the music for the ballet, simply called 'A Hindu Wedding.' But she made a bigger contribution than this. She was aware of a young Indian boy dabbling in dance in London, who was actually studying painting and who may help Pavlova design the scenography. The young lad was Uday Shankar, who not only designed the stage but later also partnered Pavlova. Thus, Pavlova "discovered" Uday Shankar. He also choreographed another ballet for Pavlova, 'Krishna and Radha' in which Pavlova made him partner her. A dancer was born. Uday Shankar grew to be an icon of Indian dance and not for classical traditions (the credit for that goes to Ram Gopal, discovered by La Meri) but hailed as the first "creative, contemporary dancer-choreographer." Shankar is called the Father of neo-classical or contemporary dance. This was in the mid 1930s. Four years later, in 1927, another development took place. A personable young Indian lady in London, Leila Sokhey, met Pavlova and bemoaned that though she had been very keen on learning dancing in India she could not make much headway. Pavlova immediately assigned Algeranoff to teach Leila Sokhey. Leila was none other than Madame Menaka in a later stage incarnation and did much for Indian dance in western India, based in Bombay. In 1929, Pavlova was going to Australia via India and Java. Who boarded the ship in Madras? A young bride Rukmini Devi Arundale, with her husband George Arundale. Their cabin was opposite Pavlova's and one thing led to another and Pavlova's staff choreographer Cleo Nordi inspired Rukmini to learn ballet while on the long journey! Later, Rukmini was not only to help reinstate Bharatanatyam, but also set up an institution Kalakshetra, for its teaching. Pavlova visited India for the second time in 1928-29 and Menaka worked with Algernoff and choreographed three stage dances, of which most notable was 'Naga Kanya Nritya.' Did the inspiration come from Ruth St. Denis' 'Cobra Dance'? Ruth St Denis and Ted Shawn need little introduction to world dance audiences. Born Edwin Myers, the name Ted stuck on him and Ruth was both his senior in age and experience and the pioneer of modern American dance, who gave the dance world such leading lights as Martha Graham, Mary Wigman and Charles Weidman. Martha said, "Miss Ruth opened a door and I saw into a life." Like Isadora Duncan who preceded her, Ruth was a revolutionary artiste who felt the need to break from the limitations of western ballet. She saw the salvation of the dance not so much in the rhythms of classical Greece as those of the Orient – Japan, China and India. Knowing fully well then that the western mind was not much exposed to assimilate these deeply spiritual dances, with their gestures and movements that have come down through long generations as symbols and legends, she made no attempt to reproduce them but her aim was to give a fair and beautiful translation that would help American and European audiences come closer to Oriental cultures. In this, she proved to be a catalyst. Her many dances with Indian themes like Radha, Incense, Cobra and Nautch made many come closer to things Indian and Ted Shawn was drawn to her art and her. They married and Denishawn was born! The Denishawn Co. toured India until 1932 and they trained countless dancers. When the company landed in Calcutta in 1925, they wanted to see Indian dances but found no signs of it but thanks to efforts of the American "consulate" they could meet some nautch dancers, that too on the 18th day of their 20 day stay! As Ted Shawn later wrote to India's father-figure of Indian dance history, Mohan Khokar, "During British rule of India, dancing was frowned upon, due to mistaken norms of prudery and all the Indians we met were embarrassed when we mentioned the word Nautch to them."  The Shawns were fortunate to meet star performers of the day, Bachwa Jaan and Malikka Jaan, both professing Kathak but of the Kotha variety. Kotha means a brothel. Ruth got so ecstatic seeing them dance, she got up as if in a trance and danced. Seeing her dance, Bachwa Jaan gave her the ankle bells she was wearing, a sign of highest affection and regard an Indian dancer can give other in courtly etiquette. They travelled through India and performed in Calcutta (Empire Theatres), Karachi (where they came in contact with young Muslim boys dressed up as girls and dancing a variety of Kathak) and met Pt Hiralal, a Kathak exponent from whom they learnt Mohr Dance or Peacock Dance. They next went to Darjeeling where at the Bhutia Monastery they managed to see some Tibetan dances and in south they went to Madurai and Madras, where seeing Mahabalipuram, Ted was inspired to compose the Dance of Siva, Cosmic dancer Nataraja for which he got made a huge brass of ring of Shiva's fire made in metal by a Calcutta foundry, at centre of which he stood himself and danced as Shiva Nataraja! Many such instances and interventions, some planned others purely by chance, made many foreigners come to India in that period for inspiration and exchange. The outcome of such visits paved the way for a very focussed revival of Indian dance traditions. This role of foreigners as catalysts and creative forces that shaped Indian dance traditions and its revival cannot be underestimated. But for these foreign dancers who came all through the early 20th century, savoured and saved some of our own traditions, we may not have had a Ram Gopal, discovered by American ethnic dancer called La Meri, or yet another American dancer Ragini Devi who discovered Gopinath. Australian Louise Lightfoot came and discovered Ananda Shivaram and many such later examples abound. Writers like Dutch Beryl de Zoete and French Travernier wrote extensively on dancing in India. In the decade after this, the slow and steady revival of Indian dance traditions started and the above foreigners deserve credit for showcasing Indian dances worldwide, thereby creating not only an interest (and a market) abroad but also open the eyes of Indians to their own traditions. The thirties thus saw the revival of four principal classical styles beginning with Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Kathakali and Manipuri. For years, all writings on Indian dance, in that period, referred only to these four principal styles. It was only subsequently that the dance-dram or mellam/yakshagana traditions like Kuchipudi, Bhagvata Mela Natakam and Yakshagana got any mention in mainstream dance writing. Forms like Orissi, Chhau or even martial arts like Kalari and Thang-Ta - - so much in vogue today - - were not even known to mainstream India. Many dancers learnt two or more styles to survive and be professionally relevant in the early years after Independence. This trend continued for long, until it gave way to an amalgamation or fusion of different forms when the art of the soloist gave way to group art. Today, fusion has led to some confusion! The coming of several institutions in the decade after the visit by foreigners of note led to creation of many major institutions like the Kerala Kalamandalam, Kalakshetra, and Santiniketan, to specifically teach and nurture traditional Indian dances happened after this decade, ie, the 1920s. The offshoot of this was an engagement of traditional teachers who left their rural moorings and came to teach in big cities like Madras and much later, Delhi. Chief amongst these were Vidwan Muthukumaran Pillai, (who travelled maximum and helped propagate Bharatanatyam in two cities: Madras for12 years; Ahmedabad for two), Vidwan Meenakshisundaram Pillai (6 months at Kalakshetra) and Ramaiah Pillai (30 years in Madras). Gurus Ellapa, Kittapa and Subbaraya Pillai, all based themselves in Madras and taught many. ABHYAAS it was! It is through this early and pioneering figures that even Bharatanatyam got its style and structure, form and content, as we mostly see today. In modern times, few gurus who have distinguished themselves are the Dhananjayans in Bharatanatyam, Kalamandalam Ramankutty asan and Kalamandalam Gopi in Kathakali and Guru Birju Maharaj in Kathak. While alive, Guru Kelucharan Mahopatra did a lot for Orissi. Vempatti Chinna Satyam and Nataraja Ramakrishna in Kuchipudi. Guru Amobi and later Bipin Singh in Manipuri. All males! These are our national icons, who have furthered parampara of abhyaas mode of teaching and learning and acquiring natya. While Indian dances have reached out to most corners of the world now, thanks also to Indian diaspora, the original catalysts were a few pioneering foreigners and traditional gurus who inspired many Indians to re-look at their own dance traditions. The played a significant role in shaping the fortunes of Indian dances. Them, we salute! Male dancers and gurus and teachers helped shape Indian classical dance in first phase of revival (1920s-1950s). Some forms were also all-male like Kuchipudi, Sattriya, Kathakali and Yakshagana. Today, we see many changes and fewer males. Most teachers and gurus are females and most forms have more female dancers, than male. In last fifty years, this is the main transition. What next?  Ashish Mohan Khokar has made writing and recording dance history his mission. As a merit-lister in M.A. History from the Delhi University, he loves the process and technique of writing history and its reconstruction. He is the most sought-after biographer because of this and his 30 years of direct dance writing, with 35 published titles to credit, makes him India's reputed dance historian. With practical background in dance and theory, his opinions are much sought after and respected. He wrote as dance columnist for many magazines like India Today, First City and Life Positive. He was the dance critic of the Times of India in Delhi, then Bangalore, before starting his own dance journal - attendance - now in its 12th year of publication. As India's pioneering arts administrator way back in mid-eighties, he served the Delhi State Akademi and the Festivals of India in France, Sweden, Germany and China and worked as one of the Directors at INTACH, under PM, Rajiv Gandhi's chairmanship. He is currently on many committees and boards, nationally and internationally. attendance-india.com ; dancearchivesofindia.com |