|   |

|   |

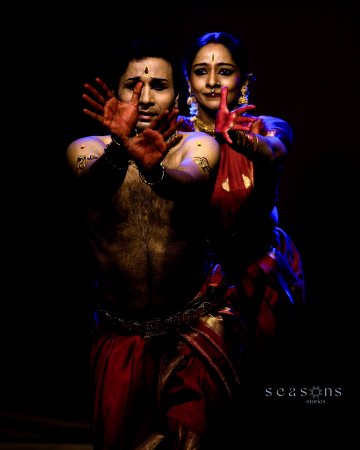

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Varied interpretations of Shakti Mahima in Nritya Samutsavam Photos: Season Unnikrishnan November 13, 2024 Nritya Samutsavam '24, curated by K.R. Manasvini, and jointly sponsored by Chennai's Charsur Fine Arts and Kala Sadhanalaya, built round the theme of Shakti Mahima, emphasized in more ways than one, the advantages of joint sponsorship, with the advantages of organizations combining resources for hosting events. At another level the event, by sponsoring dancers, both established and upcoming, each with a vocalist, not in the conventional dancer/accompanist mode, but in a coming together of talents fashioning a work with both singer and dancer contributing ideas, made for real collaboration. Here was a platform wherein, each production enriched by ideas from both sides, also entailed accommodation and adjustment, as much for the composer of music as for the movement choreographer. Being constantly exposed to expansive auditoria, with pitifully small audiences for most dance programs, it was heartening to see a space like Indira Ranganathan Trust's Sunada Lahari, where a small aesthetically conceived, covered space with a conical tiled roof, in the back garden of a modest home, becomes the performance space with an audience in front of about eighty to hundred, seated on a slight gradient. Taking serious dance back to intimate audiences, encouraging dancer/audience communication, is all to the good.  Manasvini The curtain raiser performance by curator of the event Manasvini herself, had as co-artiste the very experienced musician K.P. Nandini Sai Giridhar. Her Shakti manifestation was centered round Goddess Amba Bhavani housed in the famous Tulija Bhavani temple in Maharashtra built by Maratha Mandaleswara Maradeva of the Kadamba dynasty of the 12th century. One of the 51 Shakti peethas, the main idol is a Swayambhu murti (self-manifested) made of Shaligram. Manasvini's invocation was based on an energetic Marathi Gondhal song Gondhal Ali Ali Ho Gondhal, urging the sleeping Goddess to rise (Udhe Udhe) and bless the people. Adi Shankara's Bhavani Ashtakam formed the centerpiece of the recital. The devotee, while confessing to a life which is not blameless, in a mood of complete surrender, seeks protection of the Goddess - in water, in fire, in the mountains, hills and forests and against enemies - and in old age when weak and lost in miseries. 'You are my only refuge. I know no punyam nor have I been on pilgrimages. I know of no Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, or Lord of the Devas, nor Surya or Chandra.' Set to a ragamalika beautifully sung, the dancer gave an involved performance. After the heartfelt surrender, a more triumphant note was struck with the Jai Bhavani, Jai Shivaji composition of Samarth Ramdas Swami (1608-1682), the much loved and respected teacher of Chatrapati Shivaji. This temple deity as the family deity of several Maratha families, is specially associated with the family of Chatrapati Shivaji, with two of the front gates of the temple named after Shivaji's parents, Shahaji and Jijabai. Pleased with Shivaji's commitment to right conduct and justice for his subjects, the Goddess blesses him and she is believed to have bestowed on this devotee the Bhavani talwar (sword), with which to fight the enemies. The second part of the recital was conceived round the idea of 'Maya Nidra' of Shakti, which is looked upon as a metaphor for the cyclical nature of evolution with its threefold activity of creation, preservation and rejuvenation through destruction of the undivine. The Goddess enters into a three-day cosmic repose of Yoga Nidra after Vijayadashami. Set to the lullaby in strains of Neelambari, the state signifies the silence and stillness (also the state of Maya or illusion) before awakening. Kakada Aarti at dawn in the Tulija Bhavani temple signifies the awakening of the Goddess. Great significance is attached to the Nidra ritual. With the Goddess active again, the dancer showed Creation starts with creatures with life coming to existence in water, on mountains, and in forests. Apart from K.P. Nandini Sai Giridhar's vocals, the well-coordinated team effort had Dr. G.V. Guru Bharadwaj's rhythmic contributions along with percussion support, with Mudikondan Sowmya Ramesh on the veena with Sharada Narayanan's vocals.  Divya Nayar With its distinct flavour of Kerala's Bhagavati worship in ritual enactments like Padayani, Mudiyettu, Kalamezhuthu, et al, the recital by the next twosome of Divya Nayar and Bhavya Hari was fashioned round Bhadrakali, the 'fierce daughter of Shiva', ordered to destroy evil by the father and revered in this part of India as the protector of woman's honour. She is also worshipped as 'Kanthe Kali', believed to have emerged from the throat of Shiva, wherein was lodged the halahal poison he had swallowed from the ocean, emerging from Vasuki's breath used as the rope while churning the ocean for nectar by the Gods and demons. Divya proved herself a powerful communicator, with a theatrical strength imparted to the recital. It began with fragments of oral memories in a narrative of reminiscence on childhood days, when warned to be careful of the hour of dusk, which is neither day nor night, for this is the time when evil spirits are active. In the second part, after some quick moments of activity behind the tiraisheela or curtain held by two persons, the dancer emerged in all her finery as Bhadrakali, for the confrontation with Darika. Actions symbolizing emerging life in the womb with taanam singing, nature and bird sounds, Darika's arrogance and belligerence with Brahma having conferred on him the boon of not being destroyed by man or animal, and the Asura's contempt for the very idea of a woman having the power to kill him, were all communicated in quick brush strokes - epitomizing clarity in skillful brevity. Sarvesh Kartik's mridangam echoing the textures of percussion instruments of Kerala, the entire accompaniment with Bhavya Hari's singing, Srilakshmi on the violin and Ashwin Subramaniam providing nattuvangam support was of a piece with the dance. Bhadrakali cleverly discovers the secret of Darika's boon from his wife Manodhari. But after subduing and killing Darika, her whipped up blood thirst refuses to be quelled easily, and she begins destroying everything in her path, before the nurturing Mother in her is awakened by the mirror on the wall (again a belief from Padayani of Shiva sending Ganapati and Nandi to remind the Goddess in her ferocity of her children). Using Muthiah Bhagavatar's composition Mate Malayadhwaja Pandya sanjate was a good idea. And the endearing nature of raga Kamas by the singer softened the mood.  Shreema Upadhyaya Among the junior artistes were Shreema Upadhyaya and Niranjan Dindodi with Durga as the Shakti manifestation for the recital. In a program of interesting varied selections starting with verses from Durga Suktam, the recital went on to Harikeshanallur Muthiah Bhagavatar's composition Durga Devi Durita navarini in Navarasakannada. Shakti was next conceived as Brahmarideva, the manifestation Parvati took on for killing demon Arunasur who, through deep penance, austerities and recitation of the gayatri mantra, had earned Brahma's boon not to be killed by any four or two-legged creature. Finaly, the Devi with a swarm of six-legged creatures like bees, overpowers and destroys the rakshasa. The next composition had Shakti in the form of a grama devata, Devi Mariamman - (very sacred to Chatrapati Venkoji Maharaj the Maratha, who installed her in a temple in Ponnainalloor. Said to be one of the eight shakti pithas, very sacred even for the Tanjavur royal family, this devata is now equated to Parvati). Mariamman temples exist in Udipi of Karnataka and in Urwa in Mangalore. She was portrayed in the recital as the eternal Kanya waiting for her beloved Lord Shiva. The viruttam Pandorina kadalore kadayi nile sung in ragamalika portrayed Mariamman waiting eagerly for the Lord. Crestfallen at his not arriving, she discards her bangles considered auspicious for married women. The concluding item took the audience to Bengal for a glimpse of the ecstasy of Durga Pooja celebrations in Bengal, portrayed through a Bengali song in Sindubhairavi, Amar Agamoni. What one found truly special, and a wonderful finale, was the idea of Durga's visarjan, which ritually signifies according to some, the return of the Mother after successfully cleansing the earth of evil, to her marital home of Kailash with Shiva. Both Shreema Upadhyaya and Niranjan Dindodi had obviously worked hard to put together this program. In building up a recital, musical instruments along with the singer can provide, apart from special effects, more body to the accompaniment. It is very demanding for just a singer to sustain a dance recital and it is not surprising that the singer's pitch faltered on occasion - with no other supporting instrument barring the mridangam. Perhaps one instrument would have helped. Shreema was perhaps bound by the original idea of the festival curators, of just a singer accompanying a dancer with no other instrumental support, and perhaps it was too late for including instruments by the time she discovered that somewhere down the line, the original plan had been vetoed by singers and dancers. As a disciple of Praveen Kumar, Shreema has a clarity of line and profile in her movements. But despite a mobile face, her expressions with experience need to develop more of that internalized quietude, where her own persona and good looks get submerged in the character she is portraying in the dance.  Shijith and Parvathy The performance of the highly experienced campaigners Shijith and Parvathy Menon, paired with Vivek Sadasivam, showed what long standing partnership in art and on the stage, can create. With the Devi seen as Ardhanari, every little tilt of head, angled movement or frozen attitude spoke of body and mind togetherness, even without the figures touching. Following the preamble of Kalidasa's famous verse of Parvati and Parameshwar being as inseparable as word and its meaning (vak artha vivsampruktau….Parvati Parameshwaram), and recitation of beeja mantras Lam, Vam, Ram, Yam, Ham signifying the awakening of the chakras, the dancers in matching red outfits, began with Muthuswamy Dikshitar's Ardhanariswaram Aaraadhayami satatam in Kumudakri, singing praises of Shiva and Devi in complementing contrasts enshrined in one body - with the subtlest of moves by the couple standing together without even touching, highlighting the essence of the words. What an aesthetic idea with a dramatic impact to have four of their students in four corners of the performance space seated at an angle, all facing the dancers, with mikes in front of each, for reciting the 'sollus', with the couple performing in the center! Shiva as the eternal, passive, transcendent principle representing stillness and awareness with Parvati as the energizing female principle representing movement, creativity and transition, was subtly brought out. It is with Shakti joining Shiva that evolution begins, and post prayer the Alarippu syllables softly recited super imposed on the music, represent the starting of dance movement with Parvati, the activating shakti, in slow moves, while a seated Shiva in front remains more or less anchored in one place. The Devi's reactions to Shiva represent all the nine emotions. The angles in which the couple froze, in perfect positions, showed how complete the understanding was. From Navarasangi, the recital touched on the abstraction of the Lingam and on to abstract sollus with the full-blown rhythmic movement based on Tirugokkarnam Vaidyanatha Bhagavatar's Tillana in Purvi. The lighting of so many lamps for the Mangalam made for a spectacular ending. Ultimately it was a case of artistic minimalism yielding maximum results.  Smrithi Vishwanath After all the different interpretations of Shakti, dancer Smrithi Vishwanath with Abilash Giriprasad, in the Sapta Matrika representation of Shakti - Brahmani, Maheswari, Kaumari, Vaishnavi, Indrani, Varahi and Yami, chose a straight forward descriptive presentation based on known compositions. The dancer's statuesque frozen postures and a presentation which in movement and gestures faithfully followed the sahitya of the music, was not looking for anything out of the ordinary in terms of choreography. It was nevertheless absorbing, and fully held audience attention. Frequent stage appearances as the main performer in her Guru's productions apart, as a self-choreographed effort this was Smrithi's maiden attempt. Given her imposing stage presence, there is nevertheless in her dance a total abnegation of self, with the involved performance, making for conviction - with nothing beyond that aspired for. Parts of several compositions were chosen like Papansam Sivan's Amba Parashakti Jajani in Hamsadhwani, parts of Madurai N Krishnan's Pada Varnam Maye mayan Sodariye in Todi, interpretation of Varahi Vaishnavi based on Muthuswamy Dikshitar's composition in raga Vegavahini, the description of Chamundeswari as in Mysore Vasudevacharya's kriti in Bilahari Sri Chamundeswari Palayamaam extolling the radiant side of this ferocious Goddess as bestower of knowledge. The dance left behind some strong images like Indrani arriving on her vahana Airavathar, of Shakti Varahi, of snippets from Shankara's Aigiri Nandini and of solfa syllabic and rhythmic passages woven in. The lusty applause from the audience spoke for itself on how her recital was received. With Abhilash Giri for music composition and singing, Ramshankar Babu on mridangam, and Jayashree Ramanathan on layam composition and nattuvangam, C.S. Chinmayi on violin supported the dancer.  Jyotsna Jagannathan Ringing in the finale, Jyotsna Jagannathan with Dr. Brinda Manikkavachakam, had Madurai Meenakshi as the Shakti manifestation for their recital. Consort of Sundareswarar installed in the Madurai temple, the story behind this warrior Goddess whose idiosyncratic feature of a third breast disappeared on her accosting Shiva and losing her heart to him, is too well known, to admit of changes. Both Jyotsna and Dr.Manikkavachakam agreed that with the storehouse of musical material on the Devi available, starting with Swami Dayanand Saraswati's composition in Bagesri, and Lalgudi's compositions Meenakshi me mudam dehi in Poorvikalyani, Madurai Vazh Annaiye in Hamsaragini, and his Navaragamalika varnam Angayar Kanni Anandam, there was more than enough musical material with Sanskrit slokas - not to speak of musical gems like nottuswarams, handy for special effects. So, the concentration was on how to give a fresh dimension to what had been portrayed so often. While all compositions concentrated on the martial qualities of the Devi and her divinity, little was known about material on the reactions of the parents - of the father praying for a son, seeing a daughter emerge from the sacrificial fire and of the mother's consternation, even as she rocked and played with little Meenakshi, at the physical deformity. Even as the father concentrated on bringing her up like a male child, investing her with martial skills, Meenakshi's childhood could not have been easy, till one look at Sundareshwarar, changed her whole life, with the third breast miraculously disappearing. With dexterous violin effects and nottuswarams, the story of Meenakshi travelled between humanizing the story of her growing years, to the deified Goddess on the other. Between internalized moments with very little movement, and dancing in full flow, somewhere one could not avoid the feeling (seconded, one felt, by the measured audience applause at the end) that the message did not emerge with the intensity one would associate with a dancer of Jyotsna's technical abilities. Ultimately, how much can one humanize what, for centuries, has been revered in a spirit of total surrender? The accompaniment had Sudarshini for nattuvangam, Sri Ganesh on mridangam and Sukanya on the violin. The entire festival effort, on a fresh approach to old themes, has to be applauded. Experiencing such an enthusiastic response, Ranganathan Trust could, in course of time, perhaps consider upgrading the facilities in the venue with more rotating fans fixed on the exterior walls to make watching less oppressive in the sultry weather for people seated on the side.  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |