|   |

|   |

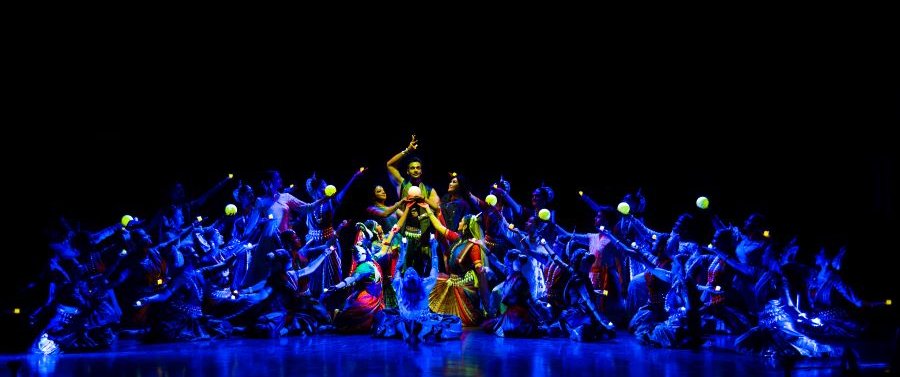

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Live dance and taped music July 10, 2024 Classical dance performed to recorded music has become an accepted phenomenon today. Even about fifty years ago, thoughts of performing Bharatanatyam or Kathak to anything but live music, was unthinkable. Sponsors, finding the cost of dance programs with live music (particularly in connection with dancers having to come from outside cities) too hard on the purse, have themselves eased earlier preconditions, agreeing to dancers performing to taped music. This always brings to mind an earlier exchange with Balasaraswati's grandson Aniruddha Knight, who remarked on how strange he found it when people referred to the word 'choreography' with regard to Padams and Javalis - for his experience with the teaching in his family, had always been to improvise on the musical line, this on-the-spot spinning of variations round one line of the music pinned on the sahitya, coming from manodharma. Nothing was pre-rehearsed, whereas now it is pre-set rehearsed rendition to music (which also is frozen in its recorded version) that has largely replaced what used to be instantaneous creativity. And not having a live singer or drummer while dancing, has added to classical dance recitals acquiring a 'packaged look.' While all dance styles have lost out with this missing live interaction between the musician and the dancer, Kathak with its life force in interactive abstract dance, with the drummer/dancer reciprocal exchange, has perhaps suffered the most. And when this dance gets reduced to 'itemisation', it loses its life force.  Keya Chanda And this is exactly what one felt in Kathak dancer Keya Chanda's presentation with her group, despite correct dancing. Trained under well-known Kathak artiste Rani Karnaa, Keya Chanda's qualifications as a gold medalist and top grade dancer, who is member of International Dance Council UNESCO Paris, cannot be belittled. Along with talented daughter /disciple Tanmoyee Chakraborty, the troupe, turned out in shining gold sequined kurta tops, no longer the mode amongst Kathak dancers of today, displayed neat 'ang' with a clean dance profile right through. In the Sargam Bandish duet, highlighting the relationship between sound and emotion, the abstract footwork finish showed excellent 'tayyari'. But rendered to the sound tape, the item lacked spontaneity associated with the tabla /peir ka kaam jawab/sawal. The Thumri 'Anmilo Sajana' portraying the virahotkhanthita, showed Keya Chanda's feel for abhinaya, the nayika here adorning herself for the expected lover who does not arrive '... na aye kajal bindiya, akhiyon me na aye nindiya,' she bemoans her lot and the empty, desolate feel in her aangan, even as the moon is out and all those who were to arrive have come. The Bhajan built round Hori play between Krishna and the gopis with all the ched/chad brought out Tanmoyee's vivacity in abhinaya. In the 'dahi mor khali matakiya phodi' showing buttermilk pots broken during Krishna's stealth of butter and buttermilk, glimpses pertained to both boy Krishna, and the slightly more grown up flirtatious teaser.  Keya Chanda & Tanmoyee Chakraborty Keya/Tanmoyee mother/daughter duo in Draupadi Cheer Haran, took on a multiplicity of roles, starting with the dice play and what followed in the Kaurava court. While the part of the helpless Pandava princes, not able to rise to Draupadi's call for help, was convincingly brought out, as was Draupadi's call to Krishna Rakh laaj hamari, the natya element went overboard in some mimetic passages. Shakuni with a limp and bent figure looked more like the caricatured Manthara of Ramayan. While emoting is important, dancers should not lose sight of the borderline between pure theatre and dance. The plate dance, much like Tarangam in Kuchipudi, is one of the Benares gharana additions to Kathak and while the high virtuosity was absent, the dancers were rhythmically correct. The tarana in Kalawati concluded the programme. BHARATANATYAM EYE COMMUNICATION IN NAYANA Photos: Sangeeta Das Banerjee Apeksha Niranjan with her eloquently expressive eyes is undoubtedly a fitting candidate for her own choreography of the Bharatanatyam program at the Stein auditorium titled 'Nayana', with its accent on the importance of the eye in dance communication. The entire verse of the Abhinaya Darpana (The mirror of Gestures) Yatha hasta tatho drishti, Yatha drishti tatho manah, Yatho manah tatho rasah,... is on the process of evoking the aesthetic sentiment or 'rasa', which cannot happen, without the total involvement of the mind. And the mind gets awakened with the eyes following the hand gesture. So it is drishti which by following the hand gesture, alerts the mind, which then gets occupied with evoking 'rasa'. So in the emotion reflected on the face through abhinaya, drishti plays a pre-eminent role. For without the eyes following the gesture, dance can become meaningless movement, not concerned with the mind. The Indian aesthetic puts great emphasis on the eyes, while describing beauty. Thus one has Meena Nayana Goddess Meenakshi - the Goddess with fish like eyes, Kamala Nayana - the Lotus eyed epithet attached to most Gods, we also have Trinayana - the God Shiva with the power of his third eye, and so on.  Apeksha Niranjan Apeksha Niranjan, who had a career in the films before taking to Bharatanatyam as a serious performer, trained under the well-known Maharashtrian Bharatanatyam dancer Sucheta Bhide Chapekar. The dancer began with Nayana Alarippu. With the wide spread of her dance movements, characterized by sharply defined geometry, and articulation of the central stylistic concerns like araimandi, alidham and pratyalidham, along with attami neck movements, with eyes following the hand movements, made for a sparkling start. This was followed by a Krishna Kavutvam a creation of Sucheta, the dancer's guru. The Marathi Mi Krishna payila showed the Gopi enjoying the beautiful form of her beloved Krishna, clad in his pitambar with tulsi mala, this naughty child who grew up to be the beloved of Radha - the dancer's speaking eyes even marking nritta summations with eye movements were very communicative. Verses from Adi Shankara's Saundarya Lahiri depicting all the major sentiments reflected in Parvati's eyes, as she gazes upon her husband, set to a ragamalika format, comprised the varnam, the centerpiece of the recital. While Parvati's eyes reflect her love for Shiva, there is a wonderstruck expression - vismayavati - as she thinks of his having consumed the entire Halahal poison, contained in his throat. But Ganga perched on his locks angers her and she is filled with jealousy. The snake adorning his neck causes Parvati fear. The power of his third eye which burns to cinders the object of its gaze, when it burns Manmatha rouses the Devi's compassion. The jatis set to various gatis, were rendered with impeccable timing with the sparkle of eyes and head movements, following gestures. While acting as punctuation points between expressive passages, the rhythm patterns also acted as a summation of a mood. Thus Parvati's angry mood at Ganga, followed by the khanda rhythm pattern echoed the aggressive mood. The music, while recorded, had a tuneful singer, though the balancing of other instruments and mridangam could have been finer.  Apeksha Niranjan A mixed inheritance (a Polish great grandfather) explains partially the dancer's ease with various languages - Sanskrit, Marathi, Hindi, English et al. The next item comprised dancing to Polish Folk Music. Here, the heroine, put off by the hero's flirtations with another girl is however reconciled when he comes back to explain that she alone is his true love - and she begins to dream of her wedding. The dance narrative set to Bharatanatyam had a certain light hearted entertainment value. After this, the mimetic items tended to be one too many and audience interest began to pall. Set in the vatsalya mode was the mother searching for the child who had disappeared after being reprimanded for partaking of food deemed as Prasad for the God in the temple. After anxious moments, she finally catches up with him, again in the process of indulging in mischief of another type. The dancer particularly mentioned the name of Smita Mahajan, yet another student of Sucheta Bhide Chapekar, who she is indebted to, who runs the dance institute Artitude and whose music compositions pertain to both the Hindustani and the Carnatic styles. The Surdas Bhajan in Shivaranjani, Akhiyan Hari darshan ki pyasi, of the blind devotee thirsting for a sight of his beloved Krishna, with sightless eyes treated to a flash of images transforming them to seeing eyes, was rendered with involvement - though by that time, audience ennui was beginning to be felt. The Tillana again was a composition of Smita Mahajan. Altogether a vivacious dancer! TRACING INTIMATE RELATIONSHIP OF WOMAN AND FIRE IN AGNEYA Photos: Sangeeta Banerjee, One Frame Story  Holika by Shree Mahamaya Arts & Culture Presented by Shree Mahamaya Arts and Culture, Dr Sreemoyee Gangopadhyay's concept of Agneya is fashioned round woman's relationship with fire from birth to death. Whether during Puja, Utsav, Vivaha, Yagna or Chitaah, the Indian woman has fire as an inseparable concomitant of life. Trained in the Debaprasad style of Odissi, Dr.Gangopadhyay dips into mythology, drawing from its episodes, a social view point associated with life even today, portrayed through multiple dance styles like Odissi, Bharatanatyam and Kathak.  Agneya by Shree Mahamaya Arts & Culture  Sneha Dev as Surya in Pranamamyaham Presented at Habitat's Stein auditorium, the opening scene for Agneya comprised homage to the fire god Agni. Pranamaamyaham or Salutation expands on the first line in the Rig Veda (Agnimile purohitam) offering prayers to the Fire God. Conceived in the Odissi style, the scene culminated with the image of the Sun God astride his horse chariot. The mardal, voicing of rhythmic syllables and the fanfare of music added up to a dramatic start, though one felt that amidst the grace, the taut power of the Debaprasad style of Odissi with its definitive chauka and strongly etched poses, very suitable for this subject, could have been accented more. The next Prajwalan scene in the Bharatanatyam style, jointly presented by dancers of SMAC and Navadrishti, visualized Agni as a symbol marking all the significant points of a woman's life. Thus the marriage vow with the couple going round the fire, and Agni as the symbol of purity was depicted through a Jatiswaram like musical composition pinned on solfa syllables. Movements had a lot of the Padma Subrahmanyam sukhalasya. Fire, finally marking the extinguishing of all mortal remains of a jiva, was sensitively treated in the choreography.  Yagnaseni by Soch Trust The following Yagnaseni scene was built round Draupadi who was born out of fire, and it was the smouldering inner fire of her anger (Krodh ki Agni) at the insults she suffered in the Kaurava court that led to the complete devastation of a kingdom through the Kurukshetra war. Choreographed in the Odissi form by Soch Trust, the scene, understandably, was full of theatre. Convincingly portrayed, the scene concluded with Dushasana's killing by Bhima, with his blood anointed on Draupadi's loose hair, fulfilling her vow that only after this act, would she tie up the tresses by which she had been dragged to court.  Agni Pariksha by Jhankaar Agni Pariksha or trial by fire in the Indian concept is based on the belief of fire as the ultimate purifier. The explanation by apologists offers two points for Rama's insistence on putting wife Sita through the fire test. One, that he knew very well that a person of Sita's purity could not be touched by fire, and two, that it was the best way of proving to his subjects of Ayodhya, that despite incarceration in Ravana's kingdom, Sita's virtue remained untouched. Be that as it may, the scene by Jhankaar in the Kathak style, lent itself to the kavit, chakkars and opening of the ghunghat in typical fashion rounding it up with dizzy chakkars, with some peir ka kaam.  Dakshayani by Nityanjali Creations Dakshayani - Blazing Retribution by Nityanjali Creations saw a blend of stylistic features, with Parvati epitomizing Nari Shakti, throwing herself into the Yagnakund of Daksha's sacrifice, with Shiva driven insane by the torture of losing his wife, carrying Dakshayani's burnt body as pieces drop off in various places to become famous Shakti peethas. The final scene touches on the metaphorical cleansing of Earth by the burning of all sins with the rains. One may cavil at the type of melodrama accompanying a performance of this nature. But it most definitely had an appreciative audience! Abhilash Talapatra as compere did a commendable job, with clarity of voice and pronunciation of the Sanskrit hymns flawless.  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |