|   |

|   |

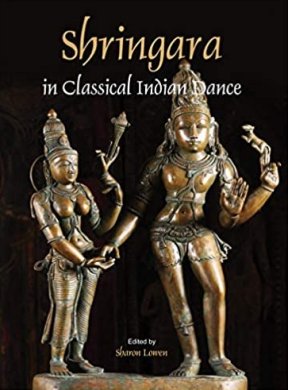

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Central to Indian aesthetic and philosophical traditions is sringar in all its facets October 18, 2022 A feature of the post Covid performance scene has been in the region of recently published books on dance. Close on the heels of Kathak Lok is Shringara in Classical Dance, brought out by Shubi Publications, edited by dancer/scholar Sharon Lowen. Its release function at the IIC Chattopadhyaya Multipurpose Hall drew a packed auditorium, and considering the all too often scanty audiences for dance performances, this kind of warm reception for book release evenings seems a bonanza. The start had two young dancers presenting Ashtapadis, suffused with the varying moods of love, in the Odissi style - the first “Pashyati dishi dishi rahasi bhavantam” wherein the sakhi, describing the state of Radha at home, languishing for her Lord, and clinging to him in her fantasy, requests Krishna to meet her forthwith.” The second Ashtapadi presented by young Vishnunath Mangaraj “Dheera sameere Yamuna teere vasati vane vana mali”, has the sakhi pleading Krishna’scase, describing to Radha forlorn Krishna’s eager wait, expecting and hoping in every soft leaf or feather falling to the ground, the gentle footstep of Radha. “Forego your pride and go to him.”  Given the combined sensual/spiritual approach to realizing divinity, India’s philosophical traditions and Arts have reveled in celebrating love in all facets and shades. Presiding over the release function discussions, Dr. Karan Singh stressed on how there could be no Indian art without divinity, and also how Indian thinking likened love’s ultimate fulfillment (Ananda) to the realisation of Godhood, pointing out “Even our Gods love to dance.” Sharon Lowen, the hostess for the evening, gave an introduction to the chapters in the book, contributed by reputed persons in each form, on Shringara. Shovana Narayan, the Kathak specialist, quoted freely from literature and poetry, in support of how wide ranging the word sringar was. The evening had its high point in Sonal Mansingh’s words, regarding her understanding of sringar rasa, which came from delving into the root of the term sringar, to fully coming to grips with its connotation. This entailed searching for and looking into ancient references from literature in Sanskrit, in Hindi and what have you, and even in all arts. What came out was one of the most erudite statements on sringar covering a vast sweep on how the Indian mind has looked at sringar. The nomenclature classical, when applied to our dance forms, is not without its undefined areas. Vilasini Natyam, the dance of the Andhra devadasi, which Dr.Anupama Kylash elaborates on, in the chapter in the book, with all its wide ranging repertoire and artistic range and subtleties, has for some reason, not been formally recognized as ‘classical’, while Sattriya has only lately in 2000 AD been certified as classical. And they were both passingly referred to as ‘folk’ traditions. Lakshmi Viswanathan, one of the most accomplished Bharatanatyam dancers trained in the Tanjavur bani, with the reputation of being one of the finest exponents of sringar in abhinaya, in her introduction on Sringar in Natya at the start of the book, mentions an important aspect of these dance forms, learning to adjust to changing needs of time. In the past, these arts practiced strictly under the Guru/shishya system, with taste shaped and dictated by royalty and nobility, the musical richness of a varnam sung and performed by the court dancer to evoke a ‘wonderful make believe world of erotic fantasy’ - had the performer’s fulfillment in the aesthetic joy or rasa experienced by the well informed rasika sabha. But today, while performing these old varnams, says Lakshmi Viswanathan, “the pertinent question is who is performing, and for whom, and where.” Being faced with the dilemma of credibility in the new context, the age old way of addressing the God, as the sole Nayaka, the dancer as eternal Nayaki seeks, demands an approach that dancers coming from a variety of cultural backgrounds today, unlike the Devadasi of the past, may not be comfortable with. So Sringar as the Rasa Raja has had to try hard to find ways to communicate with a varied, cosmopolitan audience. Dwelling on the subject of Sringar as Rasa Raja, retired Senior Director, Central Archives Doordarshan, Kamalini Dutt, also referring to how ancient the art form of Bharatanatyam is, mentions detailed references found in the Sangam poetry of Silappadikaram, with poet Ilango Adigal describing a Tamil people, living close to Nature, with both non religious and religious poetry revolving round the concept of love. Shaiva Sidhantam on the other hand, according to Sage Agastya’s Shiva / Shakti tantra, treats sringar at the metaphysical level, comprising the manifest and the unmanifest . Bhakti sringar and madhura bhakti with nayika/nayaka bhavam compositions became common. Kamalini mentions how even as the devadasi system of dedicating girls to temples to serve the Lord has now ceased, the tradition, with dance rituals conducted in the temples, still survives in Sriviliputtur and Srirangam temples. Apart from touching upon technical aspects of abhinaya centered round sringar in works like Jayadeva’s Gita Govindam and the Kuravanji Natakams, not to speak of the plethora of Varnams, Padams, Javalis, the chapter briefly mentions how sringar can be of two types - Sreyas which is uplifting, elevating and leading to spiritual fulfillment, and preyas which is pleasurable, but not sublimating. A great deal of poetry like the Andal Pasurams is centered round the pleasure of male/female relationships, while Nammalwar’s bhoga would mean “to unite with God consciousness”. The writer quotes late Balamma for whom no other emotion than sringar could reflect the mystical union of human with the divine. The chapter refers to the contemporary dancers who are re-visiting mythological characters like Seeta, Draupadi, Shoorpanakha and looking at them with an understanding centered round universal values. This chapter, in keeping with a writer who dealt with television, is illustrated with some of the finest photographs of renowned dancers. Professor Anuradha Jonnalagadda from the Sarojini Naidu School of Arts and Communication at Hyderabad, writing on Kuchipudi derived from the Yakshagana theatre, mentions how its highly dramatic character, first restricted to only male performers has undergone many changes with Gurus like Laxmi Narayana Sastry who first introduced women performers into the Kuchipudi fold - with later Guru Vempati Chinna Satyam greatly favouring the female performer as most suited to the dance form. The Kalapams, the main aspect of the Kuchipudi repertoire, with reputed performances in streevesham by legendary dancers like Vedantam Satyanarayana Sarma, whose renditions as Satyabhama made history, acquired a new flavor when rendered by female dancers - with the more bold and exaggerated gestures of men masquerading in female roles, changing to more underplayed mannerisms by women who were not playing cross gender roles. Guru Laxmi Narayana Sastry was also responsible for enriching hasta mudra in abhinaya, and his elaborate abhinaya paddhati, became a new performance manual for Kuchipudi dancers. Texts like Rasamanjari and Abhinaya Swayambodhini were translated into Telugu for dancers to equip themselves with better information and with solo depiction acquiring a new place, aside from the dance drama, sringara depiction was given more space for imaginative individual elaboration. Writing on Vilasini Natyam, comprising the ritual/ceremonial and operative dance legacy of the Telugu Kalavantulu , as the devadasi in Andhra region was called, Dr. Anupama Kylash (trained under Swapna Sundari specializing in this dance, and Kuchipudi learnt under Dr.Uma Rao), touches on how all great minds in art, from Anandavardhana to Bhoja, call shringara as the Rasaraj, its sweetness and bliss enjoyed by all creatures – rustics, animals, birds. Anupama quotes her guru Swapna Sundari on shringara “as a state of mind beyond conjugal love alone, for it is a central sentiment from which other Rasas cannot disengage…” She further speaks of love and fear as primal instincts and that love perhaps suggests its range better than the word shringara. Amarakosha, a compendium of Puranic words in Sanskrit, in its suggestion of synonyms, shows how Vilasini Natyam in all its aspects becomes a glorious celebration of shringara; the entire dance legacy of the Telugu Kalavantulu had its death knell in the devadasi abolition act of post independent India. Recasting this dance legacy with the help of historian Arudra, Swapna Sundari has helped revive parts of their traditions, Alaya Sampradayam (temple tradition, Asthana Sampradayam (court tradition), and Ata Bhagavatam which is the operative tradition of plays presented on special occasions. Her work helped reinstate the right of Melukoppu (waking up the Lord) to Lalis, Dasavatars of Lord Vishnu based on sambhoga sringara or intimate conjugal love, and Hecharikas rendered before the palanquin enters the temple. Perceived as the half divine consort of the temple Lord, the range of the shringar she could present had no restrictions, and the details mentioned in the chapter make for interesting reading. Swapnasundari is quoted saying that this shringar could not be translated through just an outward expression. What it needs is an inward explosion! Shringara in Mohiniyattam, states dancer Bharati Shivaji, with its utterly feminine Atibhanga graceful sway of the torso, delicately quivering eyebrows and foot movements with the heel touching the ground and hands moving in semi circular fashion, has a singularly captivating quality. Accompanied by Kerala’s Sopanam style music (initiated by Kavalam Narayana Panicker, who felt that the Carnatic music being used was taking away from the regional flavor of the art form) and the edakka as percussion, bhakti sringar of Mohiniattam has a uniqueness which makes it particularly suitable for expression of Ashtapadis. As a matter of fact Ashtapadi singing had a tremendous influence on the music of Kerala. Details of aharya, so specific to Mohiniattam in its all off white and gold combination, create a pristine quality of peaceful grace, over which the ashta rasas (eight emotions) sit with grace. The writer mentions these rasas epitomizing Lasyeswari, the fountainhead Devi from whom the King of rasas, sringara originated. And sringara in both its vipralambha and sambhoga manifestations becomes the main concern of the Mohiniattam repertoire. In a dance form meant only for female performers, the aspect of auchitya or high sense of propriety in seeing that ratibhava in performance never crosses the bounds of dignity is very important, says Bharati. Bhakti Sringar finds one of its finest definitions in the chapter on the Sattriya tradition, by dancer Anwesa Mahanta, and let us not forget that Sattriya presents the one and only example of the ritualistic version of the dance co-existing with its proscenium version which had its beginning only in the late1950s. She begins with the quotation from Taittiriya Upanishad on rasa, Yadvai tat sukritam raso vai sah, Rasam hi evayam labdhvanandi bhavati, where rasa took on a metaphysical dimension relating it to the supreme divinity Brahman – while centuries earlier, Bharata in his Natyasastra had expounded it as aesthetic relish. Founder of Sattriya, Srimant Sankaradeva (1449-1568) with his single minded devotion to Lord Vishnu as Krishna, embraced both ritual and proscenium art as essential parts of the same pursuit, thereby bringing about a change in all social behavior too. Hence says Anwesa, “...the rasik experience of the Sattriya dance, music and literature, nourish a performer or an audience to grow through mixed emotive fluids offering tripti (a sense of satisfaction), and moksha.” The indriyas get involved first and the emotional content leads to jnanendriyas being awakened to the Krishna consciousness. In Sankaradeva’s Parijata Harana Nat, Satyabhama would represent sensuous love while Rukmini in her humility and selfless devotion is the epitome of bhakti sringar. Ultimately, no matter what form it takes, realizing Krishna within you, whether through sensuous love or spirituality is what comprises the thematic content of Sattriya dance tradition. The texts of Sankaradeva and Madhavadeva which make up the repertoire of Sattriya dance, and the bargit songs of Sankaradeva, with love’s culmination in sambhoga sringar forming the content of lyrical compositions of the padas. Anwesa refers to the circular pattern the choreographic structure in Sattriya takes. This is the Akhanda Mandala “which is a governing choreographic structure in the ritualistic context of Sattriya dance.” Even on the proscenium platform this circularity and stillness represent an organic mix of microcosm within a larger holistic sphere of macrocosm. The dance technique in Sattriya for male and female dancers is different, starting from the basic stance where the body and energy flow in the Purush Ora and Prakriti Ora. If the males in the Sattras were expected to be proficient in both male and female roles while enacting the plays of Sankaradeva, today, with so many women performing the dance, one finds female dancers adept at performing both Prakriti and Purush roles. The writer sums up “…the constant shuffle between humane and divine, in the form of Rukmini, Sita, Gopikas and so on constantly experience the duality of aakar and nirakar, in their premapurna hridaya of Krishna - as murari and yet as the parama purush, govern the sentiment.” She quotes Harsha Dehejia who says that “sringara rasa is ultimately an acquaintance with our primal selves, making us travel from the human to the divine from dvaita to advaita.” Dancer/choreographer Dr.Shovana Narayan, in the penultimate chapter on sringar in Kathak refers to its wider connotation which goes much beyond just erotic love, as it is normally defined, thereby forgetting its large canvas including friendship, emotions involved in maternal love, hues of emotions in love from joy of fulfillment to pain of separation and much else. Shringara, the term also refers to ornamentation and here starting with the Adharam Madhuram chant of Vallabhacharya’s Madhurashtakam, to the enormity of Shiva’s ornamentation as mentioned in the opening verse of the Abhinayadarpan - draped with the entire canvas of the sky, with the earth as his garment, with the moon and stars as ornaments, not forgetting the solah sringar getup of woman, sringar has no limits. Shovana brings in quotations from Bhojpuri, wherein Shiva’s homely Bull asks for a headdress with strings of black and yellow wasps, necklace made of Patanjali’s snake with a bell hanging from it, tail adorned by colourful butterflies, deerskin seat on the back, and knees adorned by glistening frogs’ eyes. And to set it all off, a swig of bhang! After that touch of humour, Shovana refers to the Viniyog, Samyog (separation, union) moods of sringar as love, which poetry and dance revel in - with Krishna and Radha as the universal symbols of eternal love. Apart from Jayadeva and Vidyapati, the thumris of Bindadin, padas of Meerabai and Surdas, and the entire theme of “Kanha bin sooni olage nagariya” are central to sringar in Kathak. Going beyond the pale of the physical, with the idea of one being submerged in the identity of the supreme one is the poetry of Kabir, with lines like “lali mere lalki, jit dekhoon tit lal, Lali dekhan mai gayi, mai bhi ho gayi lal” about the redness of illumination where the entire world is suffused in redness, says the final word on sringar. Manipulating in several tantalizing ways the veil or choonar, to suggestively express sringar, is part of the Kathak repertoire. As the book promoter, Sharon Lowen’s writing on Shringara Rasa in Odissi forms the last chapter. Referred to between 2nd century B.C. and 2nd century A.D as the dance of Odhra Magadha, after early Buddhism of Lalitgiri and other places, Shaivism abounded from the 7thcenturyA.D, till Anantavarma Chodaganga’s temple in Puri dedicated to Lord Jagannath from the 11th century onwards, along with Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda became the central aspect dictating Odissi worship and literature and the arts. This is also the time when Maheswar Mahapatra’s Abhinava Chandrika (always mentioned as the primary source material for Odissi), was written. Sharon points out how Jagannath identified with the Krishna identity as a Vaishnavite deity, embraced Buddhist, Saivite and Tantric forms of worship. Music and dance became part of temple worship and Jayadeva’s work made Jagannath the main deity presiding over sringar, with the dance offered at the time of Bhog, and the Bada sringar when the ritually adorned God was offered love songs comprising the Ashtapadis by the Maharis in the privacy of the inner enclosure where the Gods were housed. Only the Gita Govind text could be offered to the deity according to the royal order. Special talas were prescribed for the dance seva. The chapter gives a brief account of festivals in which Maharis were involved along with the Gotipuas. During the neo-Vaishnavism of the Chaitanya era, sakhi bhava or the worship of Krishna as female devotee saw the Gotipuas leading to bandha nritya with the acrobatic karanas. Texts like Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda as part of the rituals, and Oriya compositions by poets like Upendra Bhanja, Kavi Surya Baladev Rath (whose Kishorchandanana Champu as a treasured part of Odissi music, poetry and dance has also made the champu one of the singular aspects of Odisha’s music) and Gopalkrushna Pattanayak made sringara the central concern of Odissi. The chapter apart from referring to the Sahaja cult versus the Vaishnava cult, gives the full translated text of a Champu “Kharapa tu hela re” and a song based on Gopalkrushna Pattanayak’s poetry “Patha chadi de.” The book makes for varied reading on the sheer range of how sringar, as the central concern, is treated in Indian dances.  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Response * Leela-ji, I can't thank you enough for your detailed, thorough sharing of the contents of my Shubi publications, 'Sringara in Classical Indian Dance' book and the supporting presentations at the book launch. I also appreciate the significant efforts you took to do so while still recovering your health. Very much appreciated. - Sharon Lowen (Oct 28, 2022) Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |