|   |

|   |

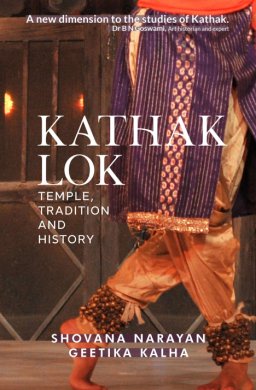

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Kathak Lok: Dimensions of temple tradition and history in Kathak September 6, 2022 A lively evening at the Multipurpose Hall of the Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay Enclave in India International Centre, marked the release of the book 'Kathak Lok' on the temple tradition and history of Kathak, authored by retired civil service officer cum Kathak teacher/performer and choreographer Dr. Shovana Narayan, and Geetika Kalha, an Indian Administrative Service Officer for over thirty years, with a background of history and extensive work on revival, documentation and dissemination of Indian art. On the discussion panel headed by the Moderator who was none other than Dr. N.N. Vohra, former Governor of Jammu and Kashmir, were distinguished persons like Ambassador Pavan Varma, well known art personality and retired bureaucrat Dr. Ashok Vajpeyi who has served as chairman of the Lalit Kala Akademi, and Art historian, critic and former Vice- Chairman of Sarabhai Foundation, Ahmedabad, Dr. B.N. Goswami. With Dr. B.N. Gowami's comment, "A new dimension to the studies of Kathak", prominently printed on the cover of the book, not to speak of Art historian and Founding Director of the IGNCA, late Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan's observations, "Absolutely stupendous work: field work most impressive" dominating the back cover, the work starts off with a heavy vote of confidence - which, whether upheld or not, will be known in time after research scholars and others read and respond to this work. Even as reactions are awaited, the panelists responded to the work in different ways. Dr. Pavan Varma felt that the information provided in the book, backed by much field work, had to be viewed against the backdrop of the edifice of India's cultural and political history - which all said and done, in a colonized country, was designed to maintain the Colonizer's preferred western-normative framework in Indian discourse, and which in independent India, needs an unbiased relook. And any researched additional information adds valuable material in helping reassess history in an Indian perspective with an indigenous worldview. After all, one cannot forget that the oldest theory of aesthetics is the 'Rasa' concept, spelt out in India's Natya Sastra. Unfortunately, with the distortions of a colonialized mind, many of us have very little knowledge of what our old texts like Harivamsh, Vishnu Purana, Bhagavat Purana or Gita tell us about culture. For Ashok Vajpeyi, the greatest point of departure in the book was that it spoke of Kathak Lok and Kathak villages, and this entire approach with villages and people who called themselves Kathak, away from the gharana politics which has presided over any Kathak discussion, was very welcome. The word Kathakaar applied to story tellers, here refers to people who practiced a form of worship in the temples comprising dissertations of poetry and dharmic literature along with singing and dancing in a totality which contained ingredients which are part of modern Kathak. The tradition is still alive in some of these villages according to the two researchers. Dr. B.N. Goswami in a lighter, modest note began by saying that it was not often that one was asked to talk before a learned gathering on something one knew nothing about! But in the process, his references covered quotes from poet W.H. Auden to Aristotle. This study with two seekers, one a classical dancer with a background in Physics, and the other a civil servant with a background in Indian culture, was not undertaken with the idea of grappling with gharanas in Kathak, chandas, rasa, sattvika or rajasika - but just out of curiosity to discover what the mention of Kathak Lok and 'Kathak Villages' that they had heard about, meant. What their journey has yielded in terms of who a Kathak was, is not in favour of, or against gharanas. But, did the germs of Kathak lie in these villages? Dr. Goswami mentioned skilled craftsmen in interior areas, who still earn a pittance for their proficiency - perhaps a reference to the fact that the starting point or sources of a movement often lie in obscurity, unrewarded. After going through the book, one realizes that there is more to these Kathak Lok than envisaged.  What seemed more than a coincidence in a hitherto unresearched field, covering over 7000 kilometres, was first locating Kathak Lok villages on the map, centered in the Jhusi area (corresponding to the area of the ancient capital city of Pratishthanpur where, according to the Natya Sastra, natya was introduced by King Nahusha) lying at the confluence of the rivers Yamuna, Ganga and Saraswati near Allahabad of U.P and western Bihar. This along with land records of Handia Tehsil thirty kilometres from here, with a large lake called Kathak Tara - and Handia is the place where Lucknow Gharana trace their ancestry - seemed promising. But what followed was a blank with vacant lands of Chak Kathak, and village Paraspur with no Kathaks - who, however, were described by the locals as a Brahmin community excelling in classical music and devotional songs accompanied with dance movements. Even the Sanskrit dictionary, Shabdakalpadruma, quoted by Shovana, describes Kathak Lok as men expanded on what religious texts say, to the accompaniment of instruments, according to rules… as experts in delineating the Katha through appropriate bhava. Raghunandan Prasad, a landlord from Paraspur, added the interesting information that Godai Maharaj alias Samta Prasad, Kanthe Maharaj as also the shenai maestro Ustad Bismillah Khan were all Kathaks! That Kathak Lok referred to a community of persons following a certain devotional calling, and not a dance form was obvious. Abandoned by Kathaks and with parts occupied by Yadavs now was Jagir Kathak, a stretch of 100 acres constituting a village granted to Kathak Lok, by rulers of Tikari State. So too was Kathak Bigha now devoid of Kathaks, donated by Tikari State whose patronage would seem to have continued till 1940. In Kichakila where Kathak Tara lake is located, the ancestral home of Late Pandit Birju Maharaj (which he curiously never visited even to pay homage at the Sati Sthal where Maharaj's great-great-great-grandmother committed Sati) again one found no Kathaks. Then there was Nasirpur Kathak, another Jagir according to the oldest land record of 1916, now empty and abandoned. Partly occupied by Yadavs, none could say why the Kathaks had left. One Pt Abdul Hamid Shastri, and Nabi Karim Bacha, a Kabirpanthi and Bhajan singer offered the information that Kathaks, Brahmins by caste, largely sported the name of Misra or Mishra and that a few of these traditional Kathak Lok lived in nearby villages Anaie and Kalan. The authors attended a pravachan of Ramcharitmanas through classical Hindustani music by Abdul Hamid Shastri, who informed them that his nephew who presented Kathak dance had learnt from Pandit Shyam Mohan Mishra of Gorakhpur. Village Kathak Purwa with a beautifully planned multi storied Madrasa and an almost entire population of Muslims, provided no direct answers as to what had happened to the Kathaks. Conversion into Islam during the British raj explained as an act to overcome the slur on Kathakiyas of being associated with Paturias or dancing girls, was neither here nor there - for it also led to the non acceptance of dance in the converted since Islam did not encourage dance, and it resulted in the Kathaks not continuing their profession. The first meeting with a lone surviving Kathak Lok family, still earning its livelihood from performing arts was at Gaur Kathak - with three brothers of a Kanyakubja family, Sachidanand Misra (gayan), Karunakaran Misra (gayan) and Satyendra Kumar Misra (tabla), whose forefathers were gifted 250 bighas of land by the Maharaja of Nepal. Shovana Narayan and Geetika Kalha were treated to a fine rendition of raga Brindavani Sarang. Further proof emerged from the meeting in Bodh Gaya collectorate where the village Isharpur (a colloquialisation of Ishwarpur) where a crumbling 1911 register mentioned the village gifted to a Kathak, Ram Dayal Raut on the orders of Tekari Raj, made by the Mughals in 1719 -'20. Once occupied by 36 Kathak families, by 1911 only 14 families still lived there. The still existing Kathak families also claimed having shifted from other villages to Ishwarpur. There was no answer when asked why the village was not named after the Kathaks - though the families asserted being Sama Veda Brahmins skilled in the arts of Vadyavidya, Nrityavidya and Natyavidya. The tradition of dance had however enigmatically disappeared in the last couple of generations - though Poojapath, music, Dhrupad, Khayal and Pakhawaj were still practiced. A professional Khayal performance was presented to the authors. Hariharpur / Kathakauli - code 193565, a part of seven villages, granted to Pt. Mohan Misra 250-300 years ago by the Nawab of Azamgarh, again provided no answer on why dance had been abandoned. In Pratappur Kamaicha and Lambuaa villages, Pt. Ashok Maharah, a relative of Pandit Birju Maharaj, spoke of 32 families engaged in temple seva with Kathaks reciting and expanding on Padas from Vedas, Ramcharitmanas and Surdas Padas, Meera bhajans etc. The public gave them money, and they also had earnings from weddings where blessings would be showered on the couple through reciting and singing padas from Ramcharitmanas, or recalling of Krishna's childhood antics. Over time, the content of the dance, as also the costume would seem to have changed, with the kurta / pyjama becoming the more convenient.This was also the time when the younger generation of male Kathaks began to associate dance with women and hence unsuitable for males. In Kathak Bigha in Amas (located with some difficulty), in a house next to the Shiva temple, the researchers met Vinay Pathak, son of Kanhaiya Malik who could trace his ancestry right from his great grandfather's time, and the village being granted to them was confirmed by land records. His ancestors were Kathaks who practiced gayan/vadan and nritta as against Kathavachaks who were reciters and sermonisers. Meeting four generations of Pt Kuldeep's family in Village Kathikanke Purwa finally established the fact that seva with or without nritya in temples comprised art forms, not in a presentational glamorous format. They were aids to substantiate what the sacred texts mentioned and spread amongst the general public they helped inculcate 'dharmic' principles upholding the code of conduct of a people. Confirmation in the census of 1892 by William Crooke, shows that as late as the near 19th century, places in the Gangetic belt like Benares, Pratapgarh, Ghazipur, Siwan, Gaya, Rae Bareilly, Sultanpur, Allahabad, Gorakhpur, Azamgarh, Faizabad had Kathaks (988 total number). What Shovana Narayan and Geetika Kalha were treated to by way of demonstrations and temple presentations by these Kathaks confirmed that the germs of Kathak dance as it exists now, were already there in what they saw in presentations from these Brahmin clans of Kathaks, for whom Ayodhyapuri is special as the birth place of Ram. Ashtayam seva in Ayodhya comprised Mangala Aarti, Vallabh Aarti, Shringara Aarti, Rajabhoga Aarti, Utthapan Aarti, Sandhya Aarti, Byaru Aarti and Shayan Aarti and Nritya Seva was during Mangala Aarti, Shringara Aarti and Sandhya Aarti and sometimes during Byaru Aarti. A string of examples from programmes witnessed are given in the book. At Charita Mandir, Satya Prakash, Pracheta Mishra at Swarga Dwar temple (now under Pt. Pracheta Mishra) danced to mnemonics kran dhadha dhadha. Abhinaya was presented to the words "Laal moriakhiyan neend jhokiaji" along with Paran kitataka thun thun natikitata ta and other pieces. Pt. Premnath Mishra alias Kuldeep treated them to "Chalo dekhiyan siya Raghubir, jhoolan wa jhool rahe" sung Khayal style. At Raamacharita Bhavan temple, a 32 year old Kathak Pt Mukesh Misra, portrayed Sita, in an uncharacteristic ched / chad role, refusing to join Rama on the jhoola because of having lost her earrings! The Kathaks also did footwork to mnemonic phrases. At Dashrath Mahal temple, sixty year old Ravi Prakash Mishra who has been doing seva for the past forty years, ever since taking over from his father, presented "Sawan aya piya ghar aye" showing rain, arrival of the beloved and the joy of tears - this joy was the ecstasy of seeing the God who was the object of love. The younger brother did abhinaya to the line "Tose lage nazariyan" (when eyes meet with the Lord), also presented a simple tukra, rela and tihai. Shovana comments on the many interpretative ideas in the abhinaya. She is struck by the seamless dance/music while interpreting a line deenam dukh haran div santan hari. Pandit Bhanu Prakash Misra at Madhuri Kunj temple presented "hindole jhoolat dore sarkar lali mere laalki" seeing little Laalki everywhere. Since 1812 when the temple was built by Maharani of Bheeshmapur estate, his family has been in charge. Pandit Omkar Maharaj presented gat nikas and footwork. When Jagdish Prasad Mishra presented kavits and padas at Raghunathji Mandir, the author mentions that no ovations of claps followed from the onlookers - instead whoever got up did so to offer 'dakshina' to the presenters. The book quotes from Prakrit and Brahmi inscriptions, from Jain manuscript of Harshacharitabhanabhat, from 11th /12th century author Kaiyata of Mahabhashyapradipa - all mentioning Kathakas as reciters, rhapsodists, followed by Sharangadeva's mention in Sangeeta Ratnakara in verse 1348 kathaka bandidinashchatre vidyavantah priyamvadah. The author also quotes several English writers who have mentioned Kathaks - Emil Schlagintweit (1880), Arthur Berriedale Keith (1879-1944) in his book on Sanskrit Drama, who refers to Kathakas and Dharakas who expand the great texts in vernacular for edification of the people, Norvin Hein in his Miracle Plays of Mathura sees a continuity of some sort between modern Kathak and Kathakara profession, Margaret Walker (2014) who says that Kathak dance as we know it today came into existence only in the 19th century. The book has two areas the findings of which are bound to raise hackles in some quarters. One is the statement that in Rajasthan even after travelling 2000 miles, no trace of villages named Kathak, nor a hereditary line of Brahmin Kathakas was discovered by the researchers and even William Crooke's census of 1892 makes no mention of Kathaks. Even in Churu and Sujangarh and the villages of Lodhsar and Badawar, the home of the Jaipur gharana Gangani family, they found Charans of whom it is said that they walk in 'Koolhatala' (born with a sense of rhythm in their blood) - said to be the hallmark of the Jaipur gharana Kathak. The summing up is that dance exponents of the present day belong to the Nagarchi, Damami or Dholi community. Dipping into the excellently maintained archives in Rajasthan States, (Jodhpur Mehrangarh Fort archives) it is pointed out that Kathaks like Shivprasad of Alwar and six others were honoured in the court. Neither Kota nor Udaipur records mention Kathaks. During the time of Maharaja Anup Singh of Bikaner (1638-1698) a Jeevandas Kathak is mentioned as an offshoot of the Benares Gharana. But with no further corroborative material, this one time mention led nowhere. From 19th century, rulers of Jaipur State extended patronage to Kathak dancers and thus rose the Jaipur gharana with its special features. Dholis have been drummers and singers. The Gangani family ancestors were great drummers by profession. The final statement is, "It is to their credit that with almost no local patron, the artistes from Churu, Sujangarh and Rattangarh regions of Rajasthan, have in a span of less than two centuries, adopted the art of Kathak dance and taken it to great heights." Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (1822-1887) is said to have learnt Kathak from Pt Durga Prasad and Pt Thakur Prasad of Handia. Rasleela of Mathura and Braj, fired the Nawab's imagination and Raas produced in Awadh court was more theatrical. Rahas took the form of dance dramas - Bal Leela, Kali Naag Leela, Makhan Chori, Kans Maru, Cheer Haran. The Nawab himself trained Kayam Khan who in turn trained the Begums. While the court had a fascination for the dance, the final statement in the book that the authors found nothing to support the claim of Mughals having influenced and shaped Kathak as a dance form, is strange. This absolute statement was criticized by all the panel members in the book release function. Why be defensive about what contribution came from the Mughal court, asked Pavan Varma? What about the Thumri which as an essential part of the dance, became a central point for abhinaya? Notwithstanding the tawaif having been looked upon by the British as a lowly person (on which there is a whole chapter in the book), can one dismiss how music and Urdu poetry contributed to Kathak? Dr. B.N. Goswami had the last word when he said that cultural history is layered with art forms being influenced by different sources. The feeling one gets while linking very old sculptures to Kathak stances, with a concluding statement, "These sculptures indicate the style of dance practiced by the Kathaks has come down unadulterated from ancient times" with a whole chapter dedicated to all terms used in modern day Kathak, of which only less than half a dozen are said to have their origin outside of Sanskrit, would seem to suggest an overwhelming desire to link Kathak with the Natya Sastra as the oldest of dance forms. As the oldest text detailing the skeletal system with movements associated with each, all dance forms will find some commonality with the Natya Sastra. Does it matter, one way or another? But no one can fault the authors for the painstaking, diligent research on whatever findings they unearthed. But for the gharanedhar Kathaks, Kathak Lok presents a whole new concept and a new dimension of Kathak .Whatever the reaction, that Kathak research has acquired a hitherto unknown, entire area of information, cannot be doubted.  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |