|   |

|   |

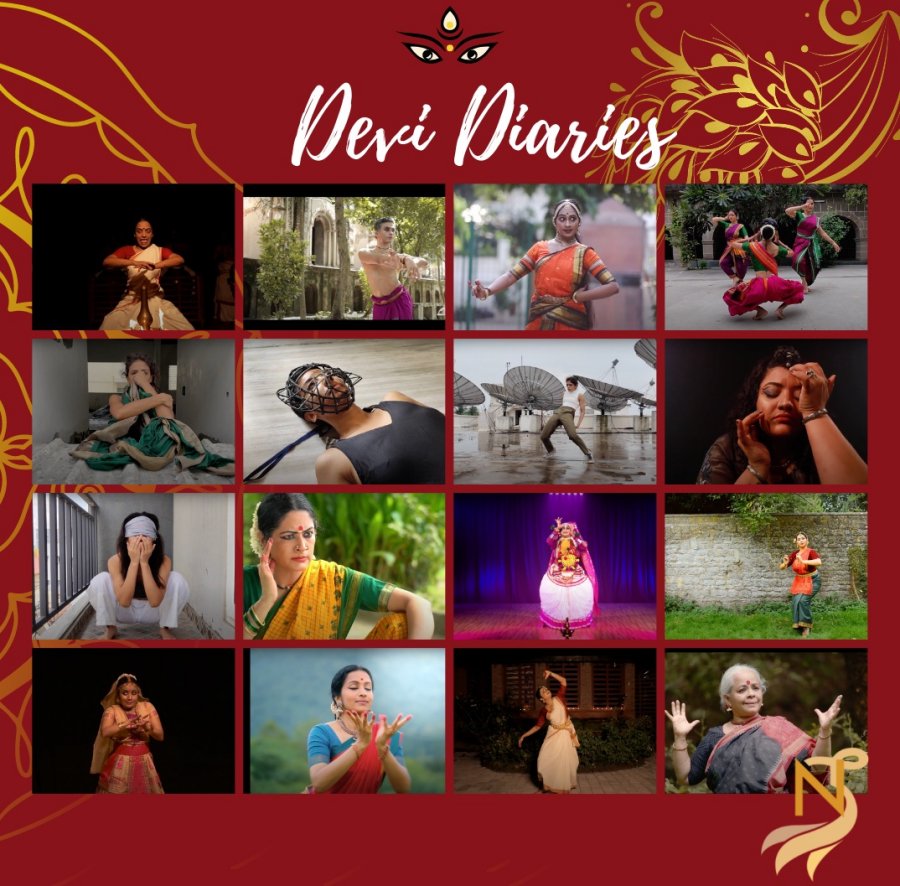

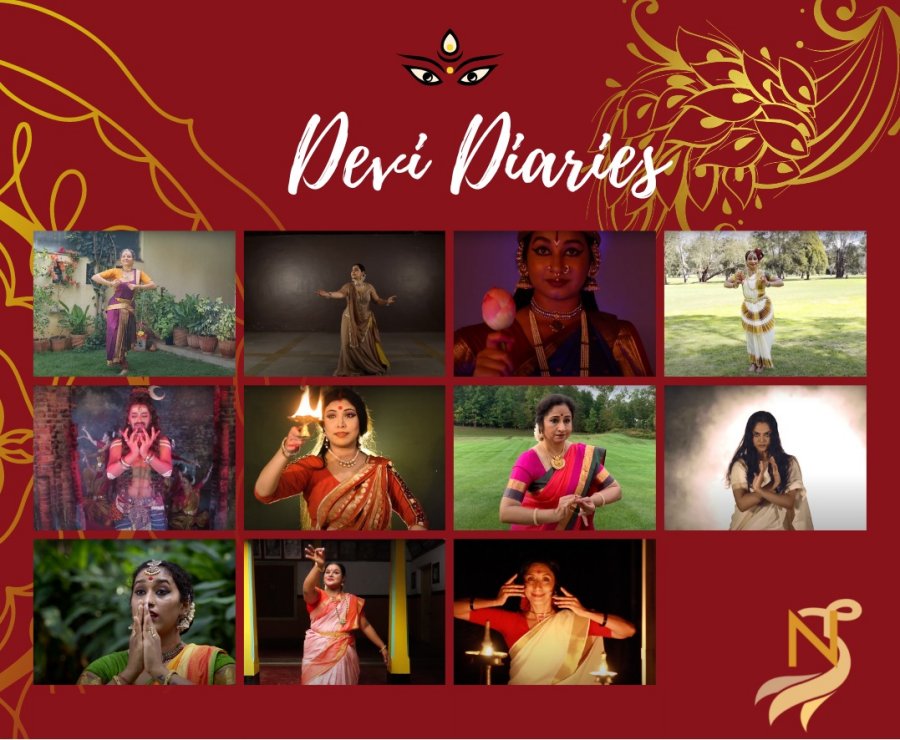

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Bewildering variety in Narthaki's Devi Diaries continues November 28, 2021 Dance expressions built round manifestations of divinised female and male energies EVERYDAY WOMAN After such a varied impression of deified manifestations witnessed in Devi Diaries, how can one forget the everyday woman in real life, whose lot, to say the least, leaves much to be desired? Narthaki, very rightly felt that sans this realistic touch, the project on the feminine mystique would be incomplete. Five young modern dance practitioners, (considering the fact that generally as a group, artists of this genre like to function in their own orbit) generously responded to Anita Ratnam's invitation, and these individual takes on woman in everyday life, make for a very interesting contrast. Flattened on her back on the floor, face secured in a steel mask with grills, Paramita Saha's goddess, the Dayvi Everyday in her home, raises herself to face yet another multitasking day, hurrying through household chores and much else - not losing her nurturing personality, or sense of joy in dancing within the small space of her home -looking at the outside world from her balcony- her equanimity and optimism undaunted, even as she faces daily challenges from systemic forces of patriarchal oppression. Apart from a convincing dance portrayal of Paramita's brief glimpse into the Everyday Woman, the work was complemented by good camera work catching all angles with clarity. There is a bit of the female in every male just as there is the male aspect in every female. But divinising and philosophising about the concept of male and female energies existing in togetherness aside, why is woman still fighting for coexistence with man? This is the question posed by Snigdha Prabhakar. Snigdha's vigorous dancing on the terrace amidst several dish antennae of the building before shifting to the interiors of her apartment, seemed to have little to do with the subject she was dealing with. The dancing seemed totally unrelated to the aspect of woman struggling for co-existence and equality. Anjana Ghonasgi's Ahalya - The Unblemished One (inspired by Chitra Divakaruni's and Kavita Kane's rewriting of mythological episodes with female characters invested with a stronger voice) made a bold statement. Based on the well known heroine from the Ramayana episode, the first part with dancer seated with legs stretched in front, communicating with just hand movements in tightly held mudras familiar to the classical vocabulary, conveyed the woman, conditioned and tailored by rigid orthodoxy and societal conventions. The tone changes with the unadorned dancer in workaday getup, assuming an erect posture in the second half, with freewheeling movements, conveying clearly the discovery and opening out of the person she really is - after chipping away at layers of her convention ridden personality - ending with a bold declaration, head high, that as the real woman, warts and all, she is her own person - and not afraid of her sensuality. I found Ronita Mukherji's Nari inspired by the poem "Miracles in the Mundane" written by Shetal Mehta, an unusual presentation. "Nari is a digital journey of a single day" the dancer says, portraying woman during this pandemic, enclosed within the four walls of the home. Coming to Modern Dance from years in Bharatanatyam, and familiar with the classical Navarasa theory of cultural aesthetics (shown in fleeting facial expressions in the presentation), the dancer's overflowing energy having to find expression within the present cramped space of four walls of the house, goes through another set of emotions emerging out of this isolated condition, where in the camera eye, she feels is a peeping Tom. The dancer diagnoses these newly felt emotional states as "Challenged, Defiant, Depressed, Choked, Surreal, Distortion, Fear, Angst, Exhaustion and Power." While the alap vocals by Nithya Shikarpur make for evocative accompaniment, the camera work could have been more resourceful in catching the dancer's moves - starting with a meditative quietude, moving on to the narrow spaces, like the edge of a cot, nimbly getting round corners and very restricted spaces. Seher Noor Mehra's Bhumi Decoded is relevant to today's world, where Bhumi Devi, the Earth, bears the brunt of being subjected to the worst misuse. Exploited and manipulated, Bhumi continues to sustain this ungrateful, unthinking humongous human population. Seher is inspired by Khadiravani, the Buddhist Bhumi Devi. She is the Goddess of the forest, who today presides over denuded concrete jungles. This unravelling of the earth story manifests in the dancer using as metaphor, yards of cloth, at times trailing behind her, at others spread on the floor she treads on or often gathered by her - with the entire lot in her hands bunched on her torso. From moving amidst azure greenery on both sides, she is reduced to balancing and performing on concrete slabs. An acknowledgement of Bhumi's bountiful giving nature, in the face of exploitation and manipulation.  Collage by Seher Noor Mehra MOOLA DURGA Facing the vast expanse of the Hooghly waters in Kolkata, Samrat Dutta's frozen stance of a broad plie, poised on a narrow cement platform on the ghat, seems to acquire an even larger dimension, as he offers salutations to Moola Durga. Similar to the Southern School of Tantra (Shree Kula) and Gaudiya Tantra (Kali Kula) are Devis Jagadhatri and Gandhaswari, worshipped in Bengal. In a presentation conceived and choreographed by Samrat, the Sanskrit Dhyana Mantra provides the textual base, set to music in raga Bhairavi and tala chatusra ekam, evoking Simhasta Sashishekhara Marakata peksha, the three eyed Devi, Durgatinashini, seated on a lion, with moon on her forehead, with Uttariya and Kankana on wrist. Apart from the vibrant nattuvangam by Santanu Roy, the majestic, excellently profiled Bharatanatyam by dancer Samrat, in both the pure dance and expressional segments, radiate with strength and dignity. RURAL AVATAR OF BHUDEVI Different from Bhudevi worshipped in Andhra temples, it is a manifestation from Andhra's folk tradition of Bhudevi largely worshipped by the peasants, that Purvadhanashree, in the Vilasini Natyam mode pays obeisance to, in a composition in Telugu, worked out in consultation with her mother Kamalini Dutt. Turned out in an Andhra handloom saree tied high, peasant fashion, with the ubiquitous water pot in hand and hair in simple knot decorated with flowers, amidst a rural setting, the dancer brings into play her delicate and resourceful abhinaya while appealing to the Mother, not to forsake her suffering devotee. "Neevu nannu mariachi naavaa?" Have you forgotten me, she asks."Of what use these eyes which do not see your resplendence, ears which do not hear you, lips which do not sing your praises or hands that do not serve you?" Alternating with the devotee's entreaties are visuals of the dancer in full regalia as the Goddess, seated in all her glory blessing devotees. Gopika Varma's serene homage in Mohiniattam dance to Attingal Bhagavathi (family deity of Travancore's royal family) is through one of Swati Tirunal's Navaratri Keertanams penned in Sanskrit, "Pahi Parvatha Nandini" sung on the last day of Navaratri. The dancer's choice of venue rings with echoes from the past. It is the Kutira Malika, Swati's palace in Thiruvananthapuram, where the royal composer created innumerable compositions, particularly in that part of the palace mandapam opening out to a view of the Padmanabhaswamy temple, with the composer imagining himself as the nayika yearning for Lord Padmanabha. The mandapam houses the ancient Saraswati image from Padmanabhapuram temple, said to have been worshipped by Kamban himself, and handed over to the Travancore royal family. Sandra Pisharody's homage, again in Mohiniattam, is based on Niram, a Kavalam Narayana Paniker composition on Kali, set to raga Dwijawanti and adanta talam. Kerala's Kavu tradition with Mother Goddess worship has a considerable following - Teyyam, Mudiyettu, Tiyattu to name a few, being examples of the same cult. Invoked forwarding off ills and healing, Malappuram's Mookuthala Bhagavathy temple and Palakkad's Parakkat Sri Bhagavathy temple are famous Kavu worship centres. Kavalam's composition gives a detailed description of the Goddess from head to toe - With feet ornamented in gold anklets, tresses like dark clouds, glowing third eye, two arms holding sword and trisula, and one hand holding demon Daraka's severed head, a stomach like a banyan tree and a mouth which reveals protruding teeth and tongue, the Devi is not without her fearsome aspects. But the involved dance, rendered in the open, against dense foliage of trees in the hinterland, in a fine blend of the interpretative, punctuated with teermanams, is replete with adoration and devotion. Far from the nimble bodied, costumed, bejewelled dancers, Jaya Rao Dayal's distinguished presence with her undisguised grey hair, dressed in her everyday attire (neatly draped Odisha saree in this case), addressing the Goddess of the Aranya, seated right in the middle of a forest, is for me perhaps one of the most striking of the Devi homages. For this devotee, Devi in her all-pervading presence can have her home only in the forest. With the accompanying music comprising a Telugu translation of the Aranyani Suktam by Vasu Nyayapathi set to a ragamalika score, she asks the Goddess why One presiding over the entire universe, chooses to have her home in the unpopulated (Nirjana Aranyana Nivasam) forest. With moving hands holding mudras and a very sensitively communicative face, holding mudras showing animals inhabiting the forest, she asks in the dark of night, "Neeku bhayame leda?" (Have you no fear at all?) 'Vishwam okate undi' - The world is one and in these surroundings I can think only of you. A very moving bit of dance theatre. This entire effort has led to dancers stepping out of rigidly laid boundaries of dance forms. Presenting Meenakshi Stotram based on Meenakshi Pancharatnam, Debanjali Biswas presents in the Nata Sankirtan style of Manipuri, a composition by R.K. Upendro, with the music a mix of the Manipuri singing by Thokchom Lansana Chanu with Carnatic music interventions by Vrinda Kandanchatha. Moving between dimly lit interiors and bright daylight outside, the photography delights in light and dark contrasts. Anwesa Mahanta's Prakriti Darshan, an excerpt from her own production Prakriti Purusha based on Bhakti literature of Sattriya dance, is built on the bedrock premise of how the Indian mind looks at creation, with female energy as the microcosm activating Purusha, the male energy. Anwesa is one of those highly involved dancers who, apart from delving into texts on Sattriya, brings out both the lyricism and the forceful aspects of Sattriya. And here with the music delightfully complimenting the dance, set to raga Vasanta and Sham in Ektali and Sutkala, her movements, given the dancer's total inner involvement, highlight the lila or play of creation (with animal life like fish, deer) set in motion by Prakriti's role in activating Purusha. Against a backdrop of luxuriant green of densely grown trees, under a blue sky, Divya Nayar's Neelayatakshi (an excerpt from Neelayatakshi Suprabhatam), sets the right tone, gently waking up the still slumbering Goddess - for the birds are chirping and fragrant flowers are awake with the sun impishly revealing his shining face in the sky - and it is time to get up. The Tamil words, beautifully sung in viruttam (for any rhythmic element would have jarred against the ambience of the item) with Divya's soft abhinaya are well matched in tone.  Collage by Seher Noor Mehra Rendered on the green patch of lawn outside the verandah, with potted plants and climbers going up pipes, Deepa Raghavan's Bharatanatyam prayer to the Goddess, Ranjanimala (a garland of Ranjani) derives as much from her neat technique with sensitive abhinaya as from Tanjavur Sankara Iyer's musical composition rendered by vocalist Karthik Hebbar, knitting into one composition, subtle variations of ragas woven round Ranjani, along with solfa passages and taanam marking punctuation points. Set to raga Ranjani, the opening, beseeching the Goddess to soothe and calm agitated hearts, describes her soft lotus eyes (mridu pankaja lochani), and delicate gait (manda agamani). Unobtrusively moving to raga Sriranjani the Goddess is visualised as Maara Janani, creator of the Love God. The song changes to Megharanjani as the Devi is visualised as protector of the clouds and rain, and the music smoothly moves on to Janaranjani when the Goddess is seen as the protector of the people. Trust Kumudini Lakhia, the Kathak guru, to veer away from much tried themes, without departing from the traditional Kathak technique. She choreographs for her disciple Rupanshi Kashyap, using late Avinash Vyas' composition in Gujarati "Maadi Tharu Kanku" saluting the powerful Goddess Amba who protects and influences her children on this earth. The main feature of the typical regional flavour of the piece, apart from the dancer's lehenga with dupatta draped the typical Gujarati way, is in the exquisite singing by the folk singer from Gujarat, Osman Mir Sa'ab. Not taking away from Rupanshi's dance, how can one refrain from reacting to such a dulcet voice! Pranamya Suri's Kuchipudi, in the usual mould, extols uniquely, Neela Devi praised by Brihaspati, Vayu and Matarishwa, who resembles the Dark Blue Lotus (karu neydal pushpam). Holding Lord Krishna Himself (who wins her hand after overcoming seven bulls) enthralled with the power of her bhoga sakti, Neela Devi, also known as Nappinnai (according to scholars, the forerunner of the later Radha), has the Lord resting on her bosom, when Andal sings her Tiruppavai. Apart from dancing on a stark white canvas, with the dancing figure standing out, the photography uses paintings of Krishna, and interiors of a temple, as door after door opens out leading to an inner shrine housing the Devi. All the way, from Natya Sudha Dance Company, Tara Rajkumar's school for Mohiniattam set up in distant Australia, comes a contribution for the Devi Diaries! I remember distinctly, seeing Tara's delightful Mohiniattam way back in the sixties! Based for years in Australia, Tara's selection for student Nithya Gopu Solomon is a Tulsidas dadra in Hindi, expressed through Mohiniattam technique set to Carnatic music involving ragas Kamboji, Kapi and Valaji! Hard to have a greater coming together of improbabilities! Authentic to the core with even kuzhitalam and kanjira in the accompaniment, Nithya's graceful dance in the wide spaces of a placid garden full of trees, ideally suits the mood of "Jaya Jaya Jaga Janani" (Hail to the World Mother). Manasa cult pertaining to worship of the snake Goddess is common to many areas in India, and folklore abounds in a culture which binds man, religion and nature into one. Offering prayers to this protector against serpents, Goddess Manasa also known as Bisahari, Janguli and Padmavati in Bengali folklore, comes a neo-classical group production in Sanskrit and Bengali, based on an excerpt from Padma Purana written by Bijay Gupt, conceived and visualised by Subhajit Khush Das featuring fine dancers from his institution Subhangik - movements in a blend of Bharatanatyam, Chhau, and folk forms of Bengal Bou Naach and Keertan. Shiva in meditative calm luxuriates in the scenes of bountiful nature in Spring (Vasant), when romance in the air with a pair of birds billing and cooing, incites the God's lust. The spilling sperm of Shiva, too hot to be contained on a lotus leaf, seeps into the underworld to take birth in the form of the Snake Goddess. (This part, in the subtitles of the text appearing right through, makes for confusing reading). It is amazing how similar this myth is to the southern myth of how Subrahmania, Shiva's son was conceived. This Snake Goddess is Hara Gowrie, Mohini, and destroyer of enemies (sarva shatru vinashini) .The choreography with several dance images in simultaneity converging in one united frame and the way movements and music blend, not forgetting the venue of a backdrop provided by the walls of an ancient monument, make for a praiseworthy presentation. From the United States of America where Bharatanatyam dancer Sujatha Srinivasan is based, comes her Devi offering, based on Muthuswamy Dikshitar's composition Hiranmayeem on Lakshmi in ragam Lalita set to rupaka talam. Worshipped all over the Universe (sarvalokaika poojite), Goddess Lakshmi who rises from the ocean in all her resplendence as the ocean is being churned, the beloved of Narayana, rejoices in music (geeta vadya vinodini). Rejecting the idea of the deity as a bestower of material prosperity, Dikshitar conceives of her as One who blesses those seeking immortal treasures. Sujatha's interpretation, based on hand gestures and expression, in the venue of the vast panorama of a magnificent park with a lake and luxuriant greenery, tends to get overwhelmed, amidst this disproportionately expansive, glorious landscape. Regarding contributions from outside India, one must acknowledge that working amongst the stringent property rights when it comes to using recorded music and with no easy access to live Carnatic music, that dancers based abroad have contributed is to their credit. Again in the Bharatanatyam form with dance based on yet another Devi composition by Muthuswamy Dikshitar, Sree Rama Saraswathi in Nasamani ragam set to adi talam, Poojitha Bhaskar from Bangalore's Upadhye School of Dance, offers salutations to Lalitambika. Restricting her action to a grass covered even ground in front of a thick growth of palms with an umbrella of trees in the hinterland, the scene offers an occasional glimpse of a home in the light peeping between branches. The dancer's lively presentation is dotted with brisk teermanams set to solfa passages, providing a counterpoint to the expressional passages, visualising the splendour of the Goddess with her nose ring, and paying obeisance to the One who complements Shiva, and is served by Mahalakshmi and Saraswati. Srikanth Gopalakrishnan's vocal support and Somashekhar Jois' nattuvangam add to the total ambience. It is always interesting witnessing a Bharatanatyam dancer, in this case Deepali Salil, moving away from the idealised Devis full of beauty, power and what have you, to a Goddess like Dhumavathi - one of the Dasha Mahavidyas - treated thematically in dance interpretation, as far as my knowledge goes, only in the Guru Debaprasad line of Odissi. Like an old widow, inauspicious and unattractive, ever hungry, thirsty and inciting tensions, this Goddess is created by smoke from the fire destroying the world. There is no deified form as such, that the dancer can emulate in the dance, for Dhumavathi represents the metaphysical philosophy of truth lying beyond superficial formal prettiness, urging one to attain the state of being, experiencing life and its truth.With hardly any dancing as one understands it, the dancer, mostly walking in the open and through attitudes, evokes an aura - clad in widow's white, enveloped in smoke haze, with the musical support in a repetitive incantatory 'Dhumavathi Sarvangapathu' along with percussion. Strikingly minimal and different! Again striking a very different and evocative note is Sankhya Dance Company's Devi visualisation of Rakhumai, believed to be a reincarnation of Padubai, emerging out of a lotus. As the divine Mother of every Maharashtrian household, irrespective of caste or creed, Ovis in praise of her are sung by women of all societal levels, even while performing their household chores. Myth has it that Rakhumai, wife of Vithala of Pandarpur, left her abode and husband to pursue a life of her own. In the concept by Pracheta Bhatt, choreographed by Eesha Pinglay, the group presentation by her in company with two other dancers Mrinal Joshi and Radhika Karandikar is based on very moving score composed by Karthik Hebbar based on Marathi lyrics written in a variety of emotive tones, by Niranjan Parandkar. Very sensitively visualised, the opening shot of a dancer's hand in a slowly opening out mudra (signifying the birth of Rakhumai) is followed by an invocation to her through an Ovis, paying salutations and describing this 'gunashalini', 'Radhika'. After a brief stint of music based on rhythmic syllables and woman shown pounding rice and performing chores - even as one bhakta is offering heartfelt prayers to the Mother, comes the concluding passage in tones of entreaty pleading that Rakhumai comes to take her rightful place in Pandarpur for they, like Vithala without her, remain unfulfilled. How each dancer in a group with separate movements became part of one cameo of three dancers and the manner in which the camera (by Sejas Mistry) caught each dancer's expressional intensity separately, were points to be noted. Dancing in the courtyard of a temple in the outskirts of Pune, the arches of the building provided a fine backdrop for the dancers' movements. Altogether a mind numbing panorama of Female Divinity!  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |