|   |

|   |

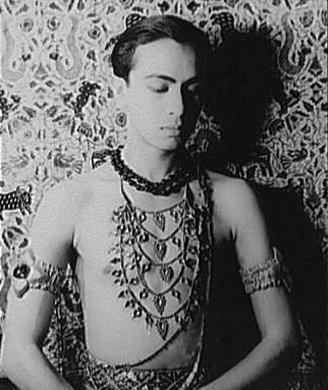

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Some refreshing moments on Internet August 20, 2020 With tastes tailored to watching live programmes, it is only lately, thanks to the pandemic that one has been forced to take in virtual discussions and exchanges, and while one must admit to still finding it difficult to watch traditional dance performances online, one must admit to some totally unexpected, interesting moments - in some of the interactions. One such episode sponsored by Jaywant Naidu from Hyderabad on 'Remembering Ram Gopal' with two main participants, namely critic and dance historian Sunil Kothari and veteran Kathak guru and performer Kumudini Lakhia provided some unintended moments of fun. After Jaywant's introduction, Sunil Kothari, as is his wont, was voluble with his diarising and volley of information on Ram Gopal, stressing on the fact that what Ram Gopal danced was vintage 'classical' - and that he was one of the earliest known dancers responsible for popularising Indian classical dances to western audiences. Following this strong reference to Ram Gopal's classical credentials, Kumudini Lakhia in her forthright fashion butted commenting that since she had to fulfil another commitment, she would like to have her say before leaving.  Kumudini Lakhia (Photo courtesy NCPA, 1976)  Ram Gopal (Photo by Carl Van Vechten, 1938) In what turned out to be an absolutely absorbing intervention by one who, as a fully trained Kathak dancer became the main dancer of Ram Gopal's troupe spending years with the master travelling, the opening remark, almost repudiated Sunil Kothari's painstakingly erected edifice of Ram Gopal's classical credentials. "Ram Gopal was never a great dancer," began Kumudini, elaborating on his very elementary grasp over technique of rhythm. Anything that went beyond 1, 2, 3 and 1,2,3,4 counts was beyond him. And since Kumudini's husband Rajanikant directed the music for Ram Gopal's compositions during a period, she knew how anything in 'khandajati' was taboo and Ram would say "change the music, this is no good" because he just could not understand how the arithmetic of multiples of 5 worked. But notwithstanding,what made Ram Gopal almost 'too beautiful to be a man' she said, was his supreme showmanship along with a refined sense of aesthetics, extreme intelligence, and an uncanny feel for how to hold the dancer's body and use movement angles to greatest advantage on stage. His understanding of stage space and the dancer's body in relation to it had few equals. And as a choreographer working with a group of bodies on the stage, he had few parallels. Having travelled with him and his troupe for quite some time as its main dancer to Italy, France, England, New York (she mentioned City Centre Theatre which is no more) and several other countries where she also met innumerable Russian dancers, Kumudini attributed her entire approach to presenting classical Kathak in group form, to her years of experience dancing with Ram Gopal. That Ram Gopal most certainly trained for classical dance under the greatest of traditional gurus, was known. But, the Guru disappeared thereafter, when he patterned an item for the stage. He dressed up, with his own creative imagination,what he had acquired from these masters, presenting the dance/dancers in an entirely original way. And Ram Gopal's influence led to Kumudini's thinking that the performed dance had to be 'free of Gurus' and that the 'Gods could be given a rest' - prompting a production like 'Dhabkar' (pulse). The 'sastras will give you the theory. But the individual dancer has to look for the pulse of the dance and find it.' Her entire search had been for that pulse - even in plain rhythm. She also acquired the precious reading habit seeing Ram Gopal's wonderful library. His excellent taste in costumes, in the way he himself was invariably turned out, the way he lived, all made a tremendous impact on Kumudini. The dancer said that what she had gained as a feel for good taste 'was more than what her mother could have taught.' Nothing but the best would do for Ram and that his rare costumes are preserved in museums abroad even now, proves his exceptional feel for costume aesthetics. Sunil Kothari mentioned that this man had such confidence in his own abilities that other highly accomplished dancers being praised, never made him feel threatened, and at the same time he had no ego problems. He often went to see Yamini Krishnamurty's dance which he admired. Kumudini spoke of 'this very sweet man's rare sensitivity for the comfort of his troupe.' In those days in places like Germany, hotel rooms were not provided with attached bathrooms and in all such places, Ram Gopal always chose a room with a bathroom for himself, making the facility available for the members of his troupe. He came across as a large- hearted rare individual. Sangeetha Chatterjee under her institution Kalpataru Arts has been arranging discussions with scholars and dancers on the aspect of 'Resurgence' during the pandemic. In her earlier pre-pandemic programmes like Saksham too, she has arranged discussions pertaining to the performative part of a performing art, which presumably has to change in content, when the medium of its presentation changes. The Resurgence discussion with Arshiya Sethi, ever full of ideas, was interesting - for here is a person who from writing, promoting, setting up institutions for presenting dance, as a two time Fulbright scholar, has dealt with dance in every which way. And from taking dance to prisoners in jail, to experimenting with the camera to create dance videos, there is nothing that Arshiya has not tried and she is perhaps the ideal person to talk on how to turn impediments into opportunities for thinking in new ways, leading to a resurgence.  Arshiya Sethi  Sharmila Biswas The other thoroughly enjoyable interaction by Kalpataru was with Odissi choreographer / dancer Sharmila Biswas -who is known for challenging time sanctioned ways of teaching and performing through her painstaking research into aspects of Odissi. What made this session particularly interesting was that it pertained to Odissi teaching for the young and with children joining dance classes from the age of eight, the challenge was to teach in a way which makes them feel engaged in activity which is natural, enjoyable and something they can relate to. At the same time, the classical verities need to be kept in mind and Sharmila's method works at arriving at a painless and automatic absorption of what the Sastras prescribe, but without that feeling of rigidity and studied distance. Unfortunately, as Sharmila herself remarked, there is no Natya Sastra or Abhinaya Darpana written in simple language for children. Since all of us are communicating to ourselves all the time, vocalising thoughts is the first part of Sharmila's 'Vachika' which a youngster needs to understand. In a sentence 'Dheera sameere Yamuna teere', each word is expressed through a mudra, and in the classroom teaching the import of how emphasis on a word can subtly alter the meaning, gets lost. But if the child takes a sentence like Today I want to play with my friends and is asked to act it out several times, with the accent changing on to another word each successive time, the understanding of the tone of the text becomes better. And Samyuta and Asamyuta hastas taught with the mudras, and acted out with changing emphasis - makes the gestural language seem much more natural to the child. Children love couplets and using these with rhythm can be fun while indirectly familiarising them with words in Sanskrit and the Sastras, otherwise tedious to learn. And one loved the children looking at the crows outside in the garden and doing their own little dance interpretations on what they saw. Our dance classes which involve a child's purely unquestioned 'anukarana' (imitation) in the beginning, if converted into a process of 'anusarana' (followed with more understanding), it would be more relatable to today's child inclined towards posing questions on the why of a movement. And Sharmila makes class fun, lacing the imitative process with a gradually deepening awareness in the youngster, where a certain strictness (like preserving the chauka) is offset with a freedom of interpretation in a blend of the theatre and dance techniques. To offset the rigidity of a body made to move in very formalised techniques, Sharmila allows the kids informal folk dance sessions like Sambalpuri dance which imparts a quality of abandon to movement. So too the abhinaya sensitivity, for the more advanced youngsters, allowed freedom of interpretation, evolves with a natural awareness for nayika levels - uttama, madhyama and adhama nayikas - without making it one flat type of interpretation which more often than not happens. And allowing the evolving dancer of today to understand shades of meaning in the text and interpret through one's own imagination to start with, means an approach that large classes of today have little time for. So too working on the character and expression of talas is an aspect that the present pandemic with less performance opportunities, allows. But what was significant in the demonstrations of the students was the way, even the younger ones, performed with a feel of having made the language their own. And to watch each Friday, one of the young dancers presented by Orissa Dance Academy in its festival 'Udayraga' with each performer given only about 18 minutes, it is heartening to know how many young dancers are emerging. Aruna Mohanty makes it a point to give her young students chances to perform. And one is astonished at the excellently trained youngsters. But my fear is, where are the platforms to give all of them a fair chance?  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |