|   |

|   |

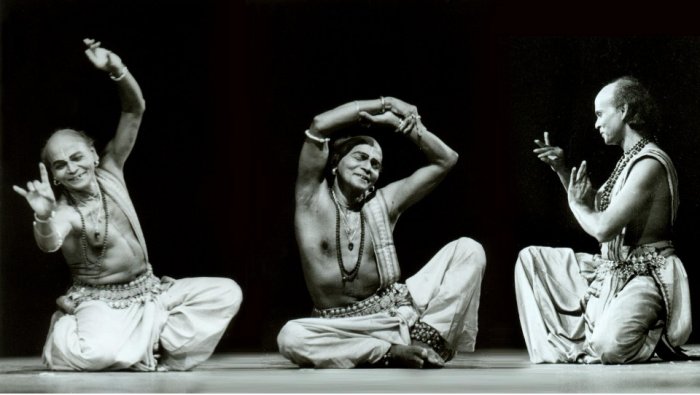

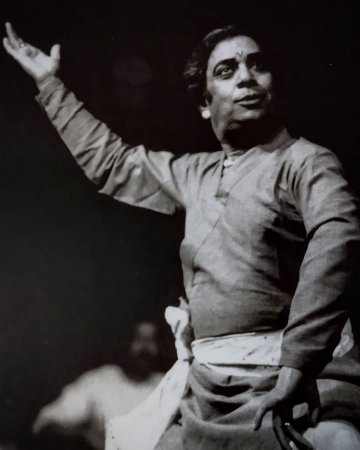

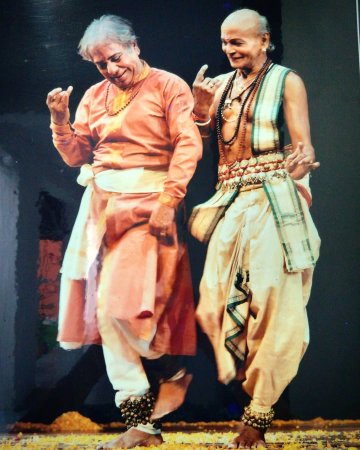

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Two post war dance stalwarts - So different yet alike July 10, 2020 But for Ratikant Mohapatra's invitation to participate along with senior critic Dr. Sunil Kothari in a discussion, under the aegis of Bhubaneswar University, based on two Padma Vibhushans - Late Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra and Pandit Birju Maharaj - I would not have had a close parallel look at the career graphs of two dance stalwart gurus who, for all time to come, have provided the reference point for Odissi and Kathak respectively. Revealing for me were points of unexpected similarity in the two very different personalities. The starting point of their entry into dance however was vastly different in each case. For Pandit Birju Maharaj, born in Lucknow in 1938 to the exalted founding family of Lucknow gharana Kathak, as the only son of Achhan Maharaj (after seven girls), with legendary Bindadin Maharaj as grand uncle and uncles in Shambhu Maharaj and Lachhu Maharaj, each a stalwart, Kathak came as a birth right and almost unwritten dharma for the torchbearer of the gharana. On the other hand, born in Raghurajpur village in 1924 - 1926, (latter according to official documents) with his birth perceived as inauspicious due to death of siblings, leading to name being changed from Madan Mohan to Sabakhy Kela or low street performer, Kelucharan's inexorable childhood love for watching Jatras and dance taught to the Gotipuas, had to constantly contend with father Chintamani Mohapatra's (a Patachitra painter) firm belief (in keeping with the times) that dance was the last resort of the truly shameless and immoral.  Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra Photos: Avinash Pasricha, courtesy: Srjan Thanks to a sympathetic mother in Siri Nani, the barely five year old secretly joined Guru BalabhadraSahu's Akhada, for three years training in the Gotipua style, till his father, in 1932, left the boy with the Raas Leela troupe of Mohan Sunderdev Goswami. Till '43, working with Sri Radha Kunj Bihari Lal Party, excelling in Vaishnav themes and role of Krishna, Kelucharan became the guru's favourite shishya - till an unfortunate misunderstanding with him being wrongly blamed, led to his quitting the troupe. Life became a toil thereafter, labouring in betel nut farms, selling paan on the street, and honing, when time permitted, his percussive skills on tabla, khol and mardal. After stints in Kalicharan Patnaik's Orissa Theatres, and Radhakant Das Party, he was finally engaged in 1945 by Annapoorna B Theatre as a percussionist. In 1946, in Mohini Bhasmasura choreographed by Pankaj Charan Das as curtain raiser for play Benami, asked to don the role of Shiva in the absence of any dancer, Kelucharan's exceptional dance talents (of which he had never spoken) were accidentally discovered - credentials finally leading to his joining Kala Vikash Kendra in 1953 as dance teacher. But Odissi itself to be recognised was fighting another battle alongside, in which the guru himself was majorly involved. Achhan Maharaj was teaching Kathak in Delhi in 1946 in Delhi's Sangeet Bharti (initiated in 1936 as Delhi School of Hindustani Music). In the same forties when Laxmipriya (by then Kelucharan's wife) danced in Ashwini Ghosh's play Abhishek, with Kelucharan playing the mardal, the British governor general taken up with the performance asked what this dance was - and the Annapurna B manager Bauri Bandu Mahanti who really had no idea, said 'Odia Natta.' (This episode has been mentioned in Ileana Citaristi's book 'Making of a Guru'). After Jayantika meetings to arrive at a consensus on the central concerns of Odissi technique along with a concert format, the dance form by 1959-60 had come into its own, entering the pan Indian stage and soon after the world stage. A dance form which even in the late forties recognised hand symbols according to actions denoted through them like (cutting off your nose - "Naako kaati dibi") Suci mudra or will push you out by the scruff of the neck - "dhakka deikiri bahar kori dibi" (a reference to the ardha chandra hand pushing a person by the neck) to have catapulted to such an exalted status in so short a time makes a rare story in history of dance renaissance, and Kelucharan was a very significant part of this eventful journey. Though Kathak was an established classical dance, Birju Maharaj did not have it easy with his father passing away in 1947 when he was but a boy (though he had already performed in places like Mumbai, Kanpur, Patna, Allahabad, Kolkata with his father), and the mother had to face both penury and hunger, till Kapila Vatsyayan (then Malik) in 1953 got young Maharaj to Sangeet Bharti to teach. What with teaching and learning and keeping up with his daily riyaz, amidst having to shift living accommodation from Daryaganj to Minto Road Railway, to Raja Bazar and finally to Hanuman Mandir, life was not easy with the young master having to tread long distances every day by foot. By 1958, when Kelubabu was in Kala Vikash Kendra, Birju Maharaj had joined the Kathak wing of the Bharatiya Kala Kendra which was to become the later Kathak Kendra under the SNA, with Maharaj as the head of the dance faculty. After Shambhu Maharaj passed away in 1969, Birju was the acknowledged heir. The rest is history. Both, multi-talented geniuses, Guru Kelucharan's wizardry as percussionist prompted then Director of AIR Cuttack, P.V. Krishnamurthy, to appoint him as AIR's mardal expert, till dissuaded by musicologist scholar Kalicharan Patnaik who pleaded that such an act would deprive the world of dance of a genius. Very skilled also in drawing (I have seen an unbelievable variety of sketches of dance poses drawn by him, inspired by observing temple sculpture), Kelucharan's artistry obviously was inherited from the Patachitra line. With hard working hands of a craftsman of delicate aesthetics, even the cone shaped beedas he diligently made every morning to arrange in his pan box, were a work of art! He built his home in Cuttack with his own hands. His enactment of Mana Bhanjana and Balya Leela and his Raas Leela performances testified to his histrionic capacities, and the impact of Odisha's Geeti Natak could be seen in his approach.  Pt Birju Maharaj Photo courtesy: Kalashram Pandit Birju Maharaj's dance genius encompasses a considerable ability for playing the tabla and singing. With his histrionic skills, he is a raconteur supreme. In 1984, when the India Festival was held in the then Soviet Union, as part of a large troupe which was sent by the ICCR, I had the opportunity of being witness to an unofficial one man show in Moscow at the hotel where the entire Indian troupe was put up, when after dinner, a sizeable crowd gathered in the verandah and lounge of Maharaj's room, as with harmonium he settled down to regale us - singing, doing abhinaya and narrating incidents from his past, holding the gathering mesmerized. Recounting a scheduled AIR singing concert, when his tablist failed to turn up, he described how as a single man, he shifted from playing the harmonium and singing to a bit of tabla play and then back to the harmonium and singing, he completed the show! Typical of his mischievous sense of humour, he silently accepted the bouquets and occasional comments of criticism of percussion suddenly going silent, from listeners who never learnt the secret of the show! As the best of performers, both gurus have transported many an audience. I remember an evening at the Kamani when Pandit Birju's Maharaj's Thaat, which today gets no more than perfunctory space in a Kathak recital (it is an intensely internalised process with minimal expression calling for deep involvement) went on for almost half an hour- emulating dance attitudes in sculpture, painting, miniature paintings and what have you - the sheer brilliance leaving the gathering awe inspired. He has himself spoken of how on being subjected to a most recalcitrant audience in Jhansi, Maharaj with images of Rani Jhansi evoked through galloping horse rhythms and a quick stepping round the performance area, soon had the audience eating out of his hands. I am reminded of Kelucharan Mohapatra taking the aesthetically set open air performance space in O.P. Jain's farmhouse, with a large gathering watching. As soon as Guruji made a slow entry emulating Radha searching for her beloved Krishna in the ashtapadi "Pashyati dishi dishi rahasi bhavantam" electricity failed and without even as much as a blink, Guruji went on miming that one line for over twenty five minutes in different ways - slowly coming down the steps and looking everywhere. Later I heard the singer say that his throat almost gave up repeating that one line countless times! Guruji went on unperturbed till the lights came on and he continued as if nothing had happened! Who has not thrilled to the evocative appeal of his "Kuru yadu nandana..". That ability to transcend body and gender and his own persona to become that which he is showing is what great art is all about. A computerised feel for laya, is another common feature of both gurus. In the Soviet Union again, asked to tailor a taal vadya kutcheri, I saw Birju Maharaj ask all the Russian percussionists to demonstrate short rhythmic sequences on their respective instruments. Within ten minutes, he had found out that their rhythm structure was largely founded on 11 matra cycle. And then he asked the Indian drum players to do likewise - and within half an hour the entire event had been rehearsed and set - and in the evening during the festival, proved a great hit. The most striking part of both these greats, given the lack of high formal education, lay in the perspicacity for deciphering the body and its movement - relating to both the dance forms. The fine tuning and streamlining of the angika aspect in Kathak is one of the finest contributions of Maharaj. I have heard him give a half an hour discourse on just the elbow which tailors hand movement but which should do so unobtrusively. Without jutting out unaesthetically, the shoulder should be discreetly tucked away from the audience. The oh so slight body weight shifts in executing footwork, and how the body needs to develop an ability to communicate beyond its physical limits, was explained to a gathering with Maharaj taking on the famous "Yatho hasta tatho drishti" from the Abhinaya Darpana - When the eyes follow the hands it is not in a concentrated squint but more as an indication of the direction the hands are moving in, taking the audience beyond just the limits of the body. "If what I am showing in dance remains confined to the limits of my body, I am no dancer. What I say with my body has to transcend and reach beyond." What a profound thought! And the reality of what Pandit Birju Maharaj was talking about is shown not just in his own dancing but came to me in a flash while I saw Guru Kelucharan conducting a workshop on the AIFAC's stage in Delhi, putting dancers of different levels through their paces in executing the Odissi Bhramari - both sadharana and vipareeta (clockwise and counter clockwise). Suddenly, putting the mardal aside, he came to the centre and taking a chauka stance, he retained it perfectly at the same level as he took a turn. The power in that pirouette was for me like the entire space where we were seated going round. The guru's feel for the body in Odissi was extraordinary. Kelucharan's insistence on the meridian (imaginary line from top to toe, dividing body into two halves) being preserved while executing a tribhangi, with the isolated torso shift being to one side, automatically creating a hip deflection was the central point of his theory in technique. Deliberate hip deflections to form a tribhangi for him were taboo. The angashuddha seen in all his students spoke for his meticulous concern for the dance profile.  Pt Birju Maharaj & Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra Photo courtesy: Kalashram A keen observation of life all round, is a quality characterising the work of both gurus. Even today, Maharaj sees everything around him in terms of rhythm and movement, and his ability to compare any rhythmic arrangement of bols through some action in daily life of animal or man, is well known. Teaching tiny tots tata thei, thhei, ta, tatheita, subzi poori, aur kachauri, with rhythm draped in terms referring to favourite snacks shows his way of reaching out to youngsters. Guru Kelucharan on the other hand, in all his compositions, has bodily attitudes he comes across in life. In a strange coincidence, with the dance drama craze in late fifties and sixties, both Gurus were involved in creating compositions in this genre for their respective institutions. Kelucharan Mohapatra's Konarak Jagaran was staged in 1958 and the same year Mahanadi was created. In 1962 came Sakhi Gopal, Krishna Gatha, Kumar Sambhav, Shakuntala (1960) and then Meghdoot. About the same time, Malti Madhav in Kathak with Lachhu Maharaj's choreography had Pandit Birju Maharaj taking on two roles. His own choreography of Kumar Sambhavam with music by Satish Bhatia in 1962, was followed by Maharaj's composing of Gitopadesh (1965), Krishnayana (1966) and based on Mirza Ghalib's poetry was Hota Hai Sabo Rosh Tamasha Mere Aage under the aegis of the Kathak Kendra. Apart from dance drama work, both maestros were at their creative peak between 1965-1990. The exceptional command of the Gurus, earned each of them the full support of the government. In Maharaj's case the Kathak Kendra, and in Guru Kelucharan's case the Odissi Research Centre rose to be top institutions in their respective dance fields. This support with musicians and all the paraphernalia needed for daily functioning being provided after, left both the stalwarts free to devote themselves to creative work. And with the institutions came talented persons who fed and inspired the ideas of the two Gurus. In Maharaj's case, late Keshav Kothari and later Jivan Pani, Directors of Kathak Kendra, ideationally enriched his art a great deal. Rising beyond representational art, Birju Maharaj's compositions like Laya Parikrama, Nritta Keli, Yati Darshan, Nada Gunjan (where an entire musical play showing only the dancers' feet clad in bells of different sizes for the notes of Mohana Sa, re, ga, pa, dha, sa) and Sampadana (portraying film being edited on the editorial table, the dancing figures moving forwards and backwards as it happens on the editing table) were works of sheer brilliance. Before entering the Research Centre, Kelucharan had absorbed ideas from Durlavchandra Singh, Dayal Sharan who taught him the basics of choreography and composing, Suren Mohanty, Kalicharan Patnaik, Shyam Sundar Kar and even P.V. Krishnamurthy. In the case of the Odissi Research Centre, musicians like Balakrishna Das and the inimitable Bhubaneswar Misra with whom Guruji shared a special bond, became valued fellow travellers in the making of a repertoire for Odissi. The music of Bhubaneswar Misra and its dance portrayal by Guru Kelucharan seemed made for each other - with Pallavis in Mohana (1965), Shankarabharanam (1965), Saveri (1966), Arabhi (1972), Hamsadhwani (1978), Khamaj (1979), Bihag (1981), Bilahari (1983), and along with this an entire suite of Gita Govind Ashtapadis -not to speak of Oriya compositions like Nahaike karidela, Dekhibo para asare, To lagi gopa danda manare Kaliya, Prana sanginire, Ahe neela sailo, Brajaku chora, Leela he nodhi to name a few. Kelucharan's profound choreographic genius has provided for Odissi a repertoire which is still a large part of what is presented. Genius is not a frequent occurrence. While a Kelucharan or a Birju Maharaj may not be on the horizon, both these gurus have ensured through hard work, a long line of highly trained students to carry forward their rich legacies.  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |