|

|

|

|

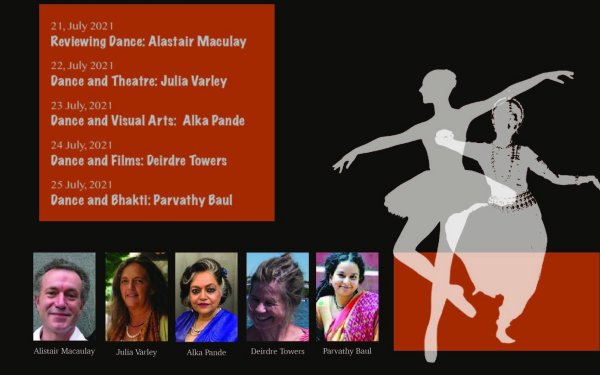

Dance across genres - Ileana Citaristi e-mail: ileana5@hotmail.com August 7, 2021 The five conversations held on-line with internationally renowned speakers for five evenings from the 21st to the 25th of July 2021 have energised my spirit in these dull and monotonous days. It was all about ‘dance’ under different perspectives, seen in a larger canvas, out of the usual confines of regional style and single variety. The event ‘Dance across Genres’ was meant to be in celebration of Art Vision silver jubilee, Art Vision@25 and was in tune with the original premises on which Art Vision was founded in 1996 by a group of artists belonging to different disciplines such as theatre, film, dance and literature with the purpose to have a common ground for exchanging ideas and experiences. Of course, during the course of 25 years much more has been added in terms of happenings, festivals, events and dance productions, but the original purpose to address art and artistic expressions from different perspectives has remained all along.  I had met the first speaker, Alastair Macaulay, during his visit to India in 2011. He was touring different institutions eager and curious to watch the dance practice and training in different styles. But it was the Odissi one which mostly attracted him and after a short permanence at Nrityagram in Bangalore, he came to Odisha and one day came also to Art Vision, sitting quietly and watching the classes in progress. Not many dance critics and historians from the West have dared to bridge the gap between the two cultures by trying to understand or at least expose themselves to an alien form of expression. Alastair belongs to the group of those few; his journey and expertise as chief dance critic for the New York Times having exposed him not only to the best of Western dances but also to quite a few Indian dance performances about which he wrote and commented. He titled his talk ‘For whom does the critic write (and why)?’ “Criticism of any art must be written for the general reader, to enlarge the world of thought and debate that surrounds each art - to enlarge culture itself. Dance and other arts must never be just for well-informed insiders.” Video: youtu.be/R3BrRSQ--rg During the talk Alastair, far from appearing as a ‘star’ icon, came out as a very sensible, human and vulnerable person. Admitting that the possibility of pleasing everybody from the part of a critic is out of question and it would result in writing blunt and boring sort of reviews, he stressed on the importance of reacting to the more intimate feelings in writing a review and externalising them through the writing, being free from the compulsion to have to please anybody. He brought out moving examples of dancers and play writers who had, during the course of his career, wrote back to him saying that his reviews, no matter either negative or positive, had meant a lot to them and even he showed a small token of thanks from one of them which he has framed and kept on his table! He described the different stages in the process of writing a review going from description to analysis, contextualisation, interpretation (including in it not only the meaning that the dancer intended as it is described in the opening pamphlet but also the meaning felt by the critic himself) ending with evaluation which according to him is important as a means of ‘connecting the heart (feeling) with the head (judgment).’ Writing a review for him means to understand his own opinion better, his own mind better and his own feelings better; he takes it as a great responsibility, the critic writes a page of ‘history’ which is there to last beyond the life span of the performance and the performer. Among the different questions which came to him after the talk, I would pick up the one about the ‘ethics’ which a critic should follow in his or her profession. In his answer he pointed to one of his main rules ‘to never meet or become friend with the artist about whom he was going to write or had written a review.’ He would never go to meet him or her in the greenroom after the performance or mix with him or her later on. Well, I thought something to ponder upon in the Indian scenario! The second evening, the conversation on ‘Dance and Theatre’ was with Julia Varley, a veteran actor of the Odin Theater of Denmark. I had met Julia in January 2004 in Hostelbro when she invited me to take part in the Transit Festival, a festival organised by her dedicated to women in contemporary theatre and again in the two subsequent sessions of the ISTA (International School of Theatre Anthropology) organised by Eugenio Barba, Odin Theater director, in Seville in November of the same year and Munster (DE) in March 2005. Video: youtu.be/1PqZ-PV1mFI She titled her talk ‘Thinking with the feet’ and dealt with the common principles for theatre and dance in her experience as actress at Odin Theater. “The performance civilisation of European origin suffers from the division between theatre and dance almost as though these were different universes of expression. They are in fact a single world which develops into distinctive genres and yet is rooted in the experience of how to let the performer’s body-mind become scenically present.” Based on this assumption, her talk started with explaining what she calls ‘organic dramaturgy’, a dramaturgy which has to do more with the impulsive reactions of the body than with the rational and intellectual ones. Through excerpts of practical demonstrations from a video recording of a session of ISTA of 1996, she described different stages in the procedure of a composition in relation with music, text, meaning and audience. The possibility of reducing an action to its impulses by maintaining its intention and meaning is what, according to her, distinguishes ‘movement’ from ‘action’; the outer form may vary but the intensity of the physical presence remains. Through the training the actor works on the common principles which underline his or her physical presence more than on narratives or stories, such as ‘how to find balance out of the centre’, ‘how the balance changes in the way of walking in different dance-theatre traditions’, ‘how to moderate the presence with soft and strong energy’, ‘how to work with different types of rhythms’ or ‘how to perform equivalent actions with different parts of the body’. Her demonstrations revealed how important is the music in her work, even a literary text is primarily put into music and then, when the musicality is removed, it is still the memory of the music to determine the accents, the emphasis and the stresses to be used in the actions accompanying the text. Using the text or the spoken language not in relation to their actual meaning but to the musical flow which is generated by the uttering of the words. It was interesting to hear how the process of composing a character or a play starts from an act of listening and reacting to an external element which can be a sound, a music, a poem or an object and slowly from the improvised reactions one come to discover how that particular character is taking shape. I observed at this point that this process seemed to be just the opposite to the one followed in the training of Indian dance since here the starting point is a very rigorous and precise grammar of the body and it is only at the end of a long period of internalisation and repetition that a sort of ’improvisation’ or spontaneity can be achieved. To this observation she replied that although one talk of spontaneous reaction it has not to be forgotten that the body of the actor has undergone a specific training and it is the particular type of training which is revealed through what his body improvises in response to the external stimulus. Rigour, discipline, repetition and rehearsal are common elements to both the processes. As common is the importance of the guru-director whose presence acts as an external eye who guides the actor-dancer and exempt her or him from the task of examining oneself. The third conversation was on Dance and Visual Arts and related to dance as ‘designed movement in space.’ Alka Pande, the art historian who is at present the consultant art advisor and curator of the Visual Art Gallery at the India Habitat Centre in New Delhi, titled her talk as ‘Dancing with Line’. “As a painter uses the brush to etch lines so does a dancer use the body to draw lines using the body as a brush.” Video: youtu.be/o5Wb2TMOiRI Her interdisciplinary presentation took the lead from the book of the renowned art historian Dr. Kapila Vatsayan titled ‘The Square and the Circle’ and from the ancient Shilpa Shastra texts which describe the human body in terms of lines, diagrams and geometric patterns. In her illustrated conversation she took us through a visual journey from the diagrams of the shastras through the dance sculptures carved on the walls of the various nata mandapa in the temples of South and North India to the pictorial representations of dance by contemporary Indian and Western painters of the 19th and 20th century. From the soft and curvilinear lines of the dancers depicted by the Impressionist painters Toulouse- Lautrec and Henri Matisse to the more geometric and stylised figures by Roy Lichtenstein and Keith Haring and the exuberant and colourful ones painted by M.F. Hussein, her presentation ended with the images of contemporary dancers such as Akram Khan and Chandralekha who had the courage to ‘break out’ of the traditional lines and to create their own designs. In reply to a question on the origin of the raga-ragini paintings, she observed how the artists of the past were Rishis who would meditate and draw inspirations for their art, either painting or sculpture or poetry, from an inner vision which would correlate emotion (rasa), knowledge (shastra) and inspiration (dhyana) in the creative process. The interrelation between all the arts is well exemplified in the story of the pupil in the Vishnudharmottara Purana who goes to the master for learning the art of painting and the master asks him if he knows the art of sculpting. To which the pupil asks the master to teach him the art of sculpture to which the master asks if he knows the art of dance and being asked to be trained in the art of dance the master asks him if he knows the art of music. An entire universe of correlations and interdependence which unfortunately in today’s world seems to have been lost and fragmented. The conversations of Dance across Genres continued on the fourth evening with Dance and Films bringing us into the heart of another important and interesting inter-relationship between the two art forms. I was in touch with Deirdre Towers, the speaker of the evening, in the early 90s when I was curating the Festival of Films on Performing and Visual Arts at Bhubaneswar and the Dance for the Camera special package for the MIFF at Mumbai. She was at that time the producer of the internationally touring Dance on Camera Festival of the Lincoln Center in New York, one of the oldest dance film festivals and she used to suggest the names of films to show for my own selection. Deirdre titled her presentation as ‘Could we be entering the golden age of dance films.’ Video: youtu.be/QPWzKrHdVv8 “Mining the treasures of dance film history to pinpoint techniques and mindsets that can be applied to contemporary dance films and exploring ways that dance films could be presented to expand our audience”. With her vast experience and exposure to dance films as curator of dance festivals for many years, Deirdre presented an excellent selection of excerpts from various dance films to illustrate the infinite possibility of utilising the camera in relation with the movements and intentions of the dance. To illustrate in how many ways the camera ‘can dance with the dancer’ Deirdre brought in excerpts of films spanning 100 years. From the silent film ‘A study in choreography for the camera’ by Maya Deren (1945) whom many considers as the mother of dance films to the fairy tale of the ‘The red shoes’ by Michael Powell (1948) to the ‘9 variations on a theme’ by Hillary Harris (1967) up to the latest ‘Bhairava’ (2017) directed by Marlene Millar and performed by Shantala Shivalingappa, the selection offered a variety of creative collaborations between the film director and the choreographer. Interesting was the observation of how the choreographer should work “as an editor anticipating how one can go from one mind set to another, one universe to another”. This is perhaps the most difficult thing to adopt from the part of a choreographer habituated to create dance for the stage where the logic of continuity which links one scene to the other is dictated by the development of the subject matter whereas the eye of the camera introduces a different logic and order of continuity and also dictates what and how it has to be seen. As equally interesting was the excerpt from Thierry de Mey ‘Rosas dans Rosas’ (1996). Thierry de Mey being a music composer and film maker all in one, starts his work by filming the sound of the dancers first and that becomes the music score on which he choreographs his camera work. She curated the selection of films not much from the chronological point of view but as she says with the purpose of showing different aspects of the film making, the landscape, the relationship with the dance and what one can do in the screen that one cannot do on stage. While she emphasised on the creative aspect of the collaboration at the same time she also launched an appeal to the dancers to give the ‘videography’ of each choreographic work the same importance which is being given for example to the light design or to the music composition. It is the responsibility of the dancers to call in the videographer and make him part of the creative process, giving him precise indications about the intentionality and meaning of the composition because while the live performance lasts only until it lives, it is the visual documentation which finally will remain for posterity. Something to be kept in mind! The befitting finale of the series of five conversations was the session on ‘Dancing bhakti’ with the Baul singer and practitioner Parvathy Baul. Parvathy is equally inspiring when she sings as when she talks; she has an inner and outer poise which conveys a sense of fulfilment in those who listen. “When the voice and body movements get together and start working in the performer’s body their relation is so powerful that a complete spiritual experience arises both for the performer and the audience”. Video: youtu.be/fADwLSrtakE Originally, the Baul masters were linked to the shakta tradition and their purpose of moving the body while meditating was to awaken the energy from the lower part of the body through the stamping of the feet and to bring it up through the various resonated in the body combining the process with exercises of inhale and exhale in a sort of ‘dancing pranayama’. Dance as spiritual mean of absorbing and calming the mind through the integration of breath and physical movement. The addition of poetry, music and aesthetic happened with the advent of the Vaishnava tradition when dance became a means of expressing the bhava incorporated in the song. The Baul singer sings and dances at the same time and the dance although based on certain basic pattern of movements, is not linked to a fixed libretto but it is a spontaneous outpour of devotion urged by the song. Being a trained dancer in Kathak style and a visual artist, Parvathy had to completely shift her understanding of the purpose of moving the body while embracing the Baul. The Baul training revolved not much around tala and beauty and precision of movements but on control and awareness of breath. The foot had to become light in raising it from the ground and even the nupur, the sacred symbol of transmission from the guru to the disciple was not the heavy lines of bells of the Kathak style but in the shape of an anklet that binds you to the ground. The training consists in the imparting and practising certain kriyas or secret movements which connect with the elements of the cosmos: the footwork with the element of fire, the movement in space with the element of water and the spinning movements with the element of ether or akash. The knowledge is handed down orally from the guru who is at the same time the spiritual and the dance guru since both the dance and the spiritual experience are combined and one is obtained through the other. This experience is not relegated to certain moments of the day but is nirvananataka, a continuous condition of surrender and the dance as a total act is complete only when this status manifests itself in every moment of the day and night. This is the moment of ‘un-learning’ when all the training and its components disappear and the surrender or bhakti is complete. After this engrossing and inspiring words, Parvathy ended with a homage song to the mysterious ektara, the humble one-string instrument capable of transmitting the cosmic sound from the ethereal world to our own.  Dr. Ileana Citaristi is an Italian born dancer, who trained under Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra in Odissi and under Guru Hari Nayak in Mayurbhanj Chhau. She founded Art Vision in 1995 in Bhubaneswar. |