|   |

|   |

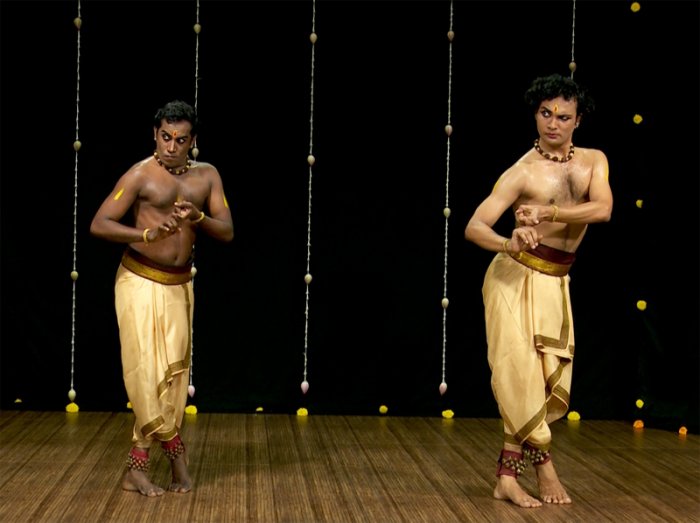

Social Media and the Shatripu - Anand Satchidanandan e-mail: anandajayalakshmi@gmail.com Photos courtesy: Bharata Kalanjali September 11, 2020 The sudden spurt in online performances and digital marketing pieces makes certain sahrudayas question what is the purpose of natya vs. classical dance today - does it only revolve around the artist's perfect formations, "collaborations" and "concepts"? Can't the performance go beyond just a personal experience? What is supposed to be the viewer's takeaway? Are they just supposed to like, share, and subscribe or actually take the effort to reflect on their actions? Most of us have heard (and few have experienced) that natyam as per the Natya Shastra has the potent ability to mentally and socially uplift those who witness it - compared often to that of performing a "yagna" of the body and soul. This was also the main need/requirement it fulfilled in the temple festivals, court gatherings etc. The Nartaka or Nartaki becomes a prism through which the audience can see the best and worst of themselves, played out through the characters presented on stage. The Itihasa, and Puranas are presented time and again to help educate, evaluate and elevate every person's dharma - from the kings to the common man. But it's quite a different story today. While many a case study speaks to the ability of social media platforms in bringing about transparency and agency for civic wellbeing, the classical arts (especially natyam) have turned mostly into a grand showcase. There is no use blaming the platforms, because that was precisely what they were supposed to do. Here, the dancer's 'showcase' and his/her ability to capture millions of netizens in 30 seconds or less - has eclipsed its content. Alternatively, allow me to share one recent online performance that was able to tweak the narrative of a Bharatanatyam piece (within the traditional format and vocabulary), to address millions digitally at a safe distance - a good marriage of both worlds! 'Shatripu: Mukti Perum Vazhi' by Gurus VP Dhananjayan and Shanta Dhananjayan on Sept 4, 2020 was a curated presentation that was in the works for 2 plus years. "The idea stemmed from a sanchari in our Kharaharapriya Nrityopaharam, but it was only now that I had the time to give it form," shares the Natyacharya. Like a kurinchi tree that blooms only every 12 years, this Nrityopaharam in a varnam format, chose this lockdown scenario and a digital medium for its birth - and how aptly so! 'Shatripu' or 'Arupagai Agatral' is a piece that explores not the usual pangs of separation, sringara, or even bhakti towards a particular deity. It takes a hard look at ourselves and at the 6 vices - kaama (lust), krodha (anger), moha (greed), lobha (miserliness), madha (arrogance) and maatsarya (jealousy ) mentioned time and again in the Vedas in preventing us from any progress in life. No gendered notions here, but just the self vs the Self. From today's political and financial news, to those detective series we read and watch - the seed of malicious intent can almost always be traced to these 6 villains. Such a blessing that our Vedas and Maha Yogis had identified this for us long before, and yet such a travesty that we have yet to learn our lesson! Knowing these basic human traits that cut across all strata, and more importantly acknowledging their presence when it slips in unannounced in our own minds is the first step to reconciliation. "One should try to get rid of them from an early age with the right kind of moral education," says the Natyacharya, "Natya, being a visual medium of education leads us to Bhakti maarga, (path of devotion) and should be used to communicate this philosophy through creative ideas." And a creative collaboration it was.  Orchestra The link opened to an aesthetically decorated stage, with professional lighting and live musical accompaniment balanced beautifully for the screen. After the customary introductions, the lead dancers of Bharata Kalanjali, Uttiya Barua and Sivadas Rajan presented a Panchanadai alarippu composed by Shanta Dhananjayan. The piece had interesting alliterations of the traditional alarippu adavus in different jaatis, making for an intricate start to the evening. The evening concluded with a remembrance to Natyacharya CK Balagopal by his daughter Prithvija with the well-known Hindolam Khanda Eka Thillana. The main presentation of the evening was a new Nrityopaharam entitled 'Arupagai Agatral' (expel six enemies). The lyrics were in simple chaste Tamizh penned by Nirmala Nagarajan of Kalakshetra, and tuned by Dr. Vaanathi Raghuraman. Couplets for each of the vices had a very similar treatment to the Tirukkural - describing the vice and its effect on us. The beauty of the kavitvam came to light with a recitation of the verses first, followed by melody and finally finishing off with swarams or jatis. The swara (musical notes) passages were composed by Shanta Dhananjayan and jatis and natya composition by V.P. Dhananjayan. Another interesting choice was the usage of 'jati-sanchari.' "We did not use the usual format of varnam pattern, but used the jatis as communicative expressive narration of certain ideas taken from the Puranas, Panchatantra and contemporary incidents." Kaama (lust) was elucidated through a quick jati-sanchari of Indra's escapade with Ahalya. Krodha (anger) brought back the well-known Panchatantra tale of a mother beating her pet mongoose for having harmed her child, when it had in fact defended the child from a snake attack. Moha (greed) was a contemporary take on present day politicians and businessmen who seek to possess material wealth and power only to pass away alone. Lobha (miserliness) recalled the nose ring episode that made Purandaradasar realize his miserliness. Madham (pride) showed a quick exposition of how an arrogant student, who disrespects his Guru, meets his doom in no time. Lastly, maatsaryam (jealousy) also hit close to home - recounting the unhealthy competition between two dancers a la Vanjikottai Valiban.  Sivadas Rajan and Uttiya Barua The uniqueness of the jati-sanchari composition lies in its efficacy - testing the Nartaka's ability to communicate with minimal gestures, time and iterations. Announcements of the sancharis ahead of time helped the trained eye to follow through on its quick delineation, but could likely be missed by a wandering audience. The seed of creativity, however, has been sowed again by the innovative dance couple for the community to consider - very similar to the swara-sanchari innovation in their Attana Nrityopaharam way back in 1967. The performers per se showed strong dedication towards the task at hand. The nritta passages had signature new adavus, hinting at the sthayi bhava to follow with the usage of specific hastas and adavus. For the right rasottpatti, a medley of ragas were chosen from Kamavardhini (Pantuvarali for kaama - lust), Kannada (krodha/anger), Ratipatipriya (moha/greed), Kuntalavarali (lobha/miserliness), Mukhari (madha/pride), and Vaagadheeshwari (maatsarya/jealousy). One notes that while depicting a series of vices, it is easy to slip into a single-faceted approach and mukhajabhinaya. The lines get especially blurry between kaama, moha and lobha, all commonly driven by a unappeasable want to own. Krodha and maatsaryam by Sivadas Rajan, and moha by Uttiya Barua showed good balance of angika and mukhajabhinaya, displaying the different stages of intoxication and repentance in quick succession. The need for such innovations is self-explanatory. Its presentation takes us to the first level of realizing that the enemy and obstacle to spiritual growth lies within. Multiple puranas, itihaasa, slokas, tevaram, paasuram and prayers across religions speak to this. But what is truly noxious, which we encounter every day, is the surreptitious manner in which it infects the mind, clouding all objectivity and judgement. In most cases, all this happens behind the veil of civility. This duality can be explored more by the performers of this piece. In this way, as one pens his thoughts, one realizes there is a strong resemblance between the Shatripus inside and the Corona outside. It can come from anywhere, anyone, anytime, only vigilance and distancing can help. The time has come to better enable the divine art form to educate, evaluate, and elevate this truth. The credits include: Nattuvangam by Shanta Dhananjayan, vocal by Shalin M Nair, violin by R Kalaiarasan, mridangam by KP Ramesh Babu, stage and technical direction by CP Satyajit. Anand Satchidanandan is a Bharatanatyam practitioner, Director of the Shanmukhananda Natya Vidyalaya, Mumbai, and Associate Director of Consumer Science & Research at Nepa India. |