|   |

|   |

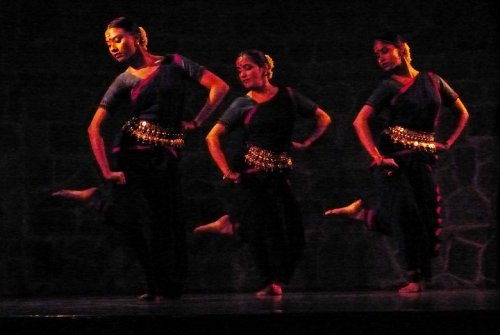

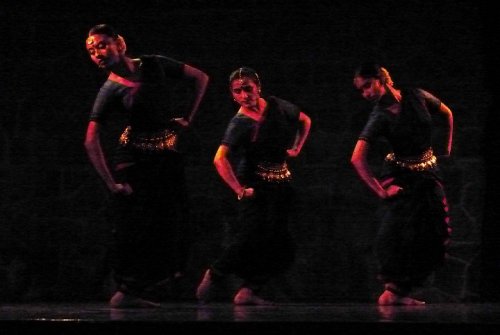

Dancing in Stillness - Shrinkhla Sahai e-mail: sahai.shrinkhla@gmail.com Photos: Avinash Pasricha April 14, 2019 Three dancers emerge on stage, moving in silence. The slow, elaborate head movements gradually expand, spanning the torso and forming distinct movement patterns with pointed gazes. The musicians wait quietly, the audience watch with abated breath as the dancers move to the sound of stillness. The regular Odissi outfit, sans ghungroos, indicates an exploration of traditional aesthetics with a minimalist soundscape. For Singapore-based dancer and choreographer, Raka Maitra, her latest production Pallavi in Stillness is a move away from music and a dive into the detailed geometry of the dance form. Performing in Delhi after a long hiatus, the artist presented a composition that reimagines the fast-paced Pallavi from the classical Odissi repertoire as a meditative, slow study of postures, movements and silence. Blurring boundaries A disciple of Odissi dancers Madhavi Mudgal and Daksha Mashruwala, Maitra has also trained in Seraikella Chhau under Shashadhar Acharya. She positions her choreography at the edge of the classical and contemporary, blurring concepts and melding movements. Reflecting on her artistic journey, she points out that moving away from India was an important factor in discovering her own niche. "The disconnect from the roots is also important at times to start afresh. Moving to Singapore gave me an opportunity to begin my training and build my own practice with a new perspective, the way I wanted." In Singapore, Maitra started out as an associate artist with The Substation - an art space that supports experimental artists and in 2014 she founded Chowk Productions. As the Artistic Director of the institute, Maitra has designed unique methods of training. The dancers focus only on learning Pallavi- the technique-based composition from the Odissi repertoire. "The technique of pure dance interests me the most," says Maitra, "we don't train in abhinaya even though I love watching it."  The pace remains slow, measured and consistent throughout the work, which also brings in some monotony. The performance skirts any high points and the rhythm sinks into familiarity, not offering many surprises. "I didn't want to create any such moments," says Maitra, "I know it is a risk and maybe people expect that but I like challenging myself and wanted to see whether this would work the way it is." Sound and silence Another unique aspect of the practice at Chowk is that the dancers train in silence, they do not move to music. With a dearth of musicians for Indian classical dance in Singapore, Maitra started developing her compositions in silence. This later became an integral part of her process. The sound design for all her productions are done towards the end, when the choreography is ready and can be danced to any music, or without it. "I develop the work for about three months in silence, and then three weeks before the performance the musicians join in." For Pallavi in Stillness, music is bare and sound is used to support the movements. The Tibetan singing bowl makes its way into the work, followed by humming, alaap, body rhythms, bells and other unusual elements. Trained in theatre, the trioŚLakshman KP, Uma Katju and Caroline Chin create a sound design that compliments the choreography yet remains inconspicuous. While ghungroos were used in the same piece when it was performed earlier in Singapore, Maitra decided it was 'very noisy' and for the first time, at the performance in Delhi, the ghungroos were removed. Bodies in space Alongside Karishma Nair and Sandhya Suresh, Maitra was one of the dancers in Pallavi in Stillness. The trio mostly move as one unit throughout the piece. It might have lent more variety to the visuality of the work if there were more formations in space as well as have each dancer explore distinct patterns and then return to the trio as a compact entity.  Maitra prefers her role as a choreographer over dancing on stage. "Even when I was learning at Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in Delhi, I knew I did not really want to be an Odissi dancer, I wanted to create something with Odissi. I got into choreography because I was clear I did not want to do the pure classical." She trained in Bharatanatyam initially and it was only in her 20s that her tryst with Odissi started. "Doing a traditional piece gives me a lot of joy, but not on stage," she says, "I was also fascinated with the contemporary dance work and wanted to explore that." The production is part of a trilogy of which Pallavi in Stillness is the third one. The first piece focused on the chowk (square stance) of Odissi, the second one explored another fundamental aspect of Odissi-the tribhanga (the tri-bent posture), accompanied by speedy rhythm work. Pallavi in Stillness evolved out of a focus on the torso movements, eyes, and stillness. Deconstructing the basic geometry of Odissi, the movement of the arms emerge only towards the concluding part of the piece and hand gestures are avoided altogether. "I do things instinctively, in all my pieces I have never used much hand gestures," explains the artist, "A classical piece is tightly knit with the music, history, postures, but when you isolate the hand gestures, they become decontextualised and cannot stand alone without the overarching classical structure." Repetition is used strategically in the choreography, with recurring movement patterns undercutting the gradual build-up of rhythm work. Deeply inspired by the legendary Odissi guru, Kelucharan Mohapatra's Pallavi compositions, Maitra reflects, "Each one of his Pallavis is unique, it has a thread, the elaboration increases within the composition, and there is a recurring body movement which gives it a unique flavour. That's why repetition is important, otherwise a Pallavi can become boring. I try to keep that thread, where I start with a movement, it evolves as the piece progresses and then I return to it." Gazing ahead Maitra usually develops the choreography on the floor, alone, in silence, and then teaches the dancers. Influenced by the Indonesian choreographers she has collaborated with, she developed many solo pieces and started producing ensemble work in 2011. "The Indonesian choreographers are very open, and you are allowed to fail. When you try something experimental it is important that you have the space to risk failing. Sometimes, in India this is hard because people can be unforgiving." Simplicity and courageous choreographic choices make Maitra's work unique and promising. Including more elements of surprise and playfulness could spark another layer of edginess to her oeuvre. Her fundamental premise is to never underestimate the audience or play to the gallery. "I feel that audiences everywhere are intelligent. If the piece has rigour and honesty, people will connect to it. So, I don't try to please the audience, I think they will respect my work, even if they don't like it, they won't dismiss it." Plugging into the absence of Indian classical-based contemporary work in Singapore, Chowk has emerged as one of the few dance ensembles working in this field. Maitra is of the firm belief that one cannot be a part-time dancer. Her vision for Chowk is to create a platform where classically-trained Indian dancers create contemporary work and can pursue dance as a sustainable career. Shrinkhla Sahai is an arts writer, educator, media professional and Therapeutic Movement Facilitator based in Delhi and Bangalore. |