|   |

|   |

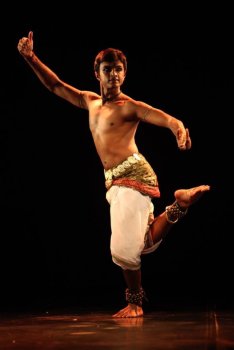

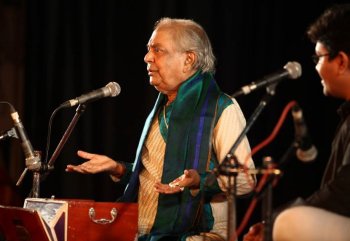

The primacy of male and female energies in the Dancing Male - Dr. Ketu H. Katrak e-mail: khkatrak@uci.edu Photos: Vivekanandan December 26, 2013 I can say everything is rhythm. Life is rhythm. Rhythm is God. - Pandit Birju Maharaj The rasikas on the final day (December 22, 2013) of PURUSH: The Global Dancing Male, were entranced by stupendous performances at Chennai’s Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan that evoked via movement, music, sound, lighting,words, and use of space several important provocations that this 5-day conclave of papers and performances had raised - what makes a man or a woman? How much of our gendered identities as man and woman are determined by external clothing and accouterments, and how much by our inner sensibilities? How do we inhabit our external physical male and female bodies and our unseen male and female energies that breathe through our muscles and bones? How do we explain the power and beauty of a male dancer in stree vesham transforming into a female, even as we enjoy male dancers performing tandava and lasya in equal balance? How do we take further our notions of sexuality by recognizing the significance of crossing boundaries of narrow definitions of sexual identities as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, and transgender? How do we redefine what is considered “normal” in society? How do we confront regressive legislations as the recent passage of 377 criminalizing homosexuality by India’s Supreme Court? How do we find the courage to openly respect and include the many personal and sexual choices in our human community? The evening’s magic began with Hari Krishnan’s choreography of Uma, danced in stree vesham by N. Srikanth with memorable subtlety, beauty and grace. The evening’s feast ended with the legendary Kathak maestro, Pandit Birju Maharaj performing Baithak Bhav in which he captivated spectators with his soulful singing and abhinaya, speaking with his eyes, voice, and torso. In between Uma and Baithak Bhav, two artists - Parshwanath S. Upadhye’s Bharatanatyam rendition of Purushaardham: the male half, and Kalakrishna’s Andhra Natyam portrayal of Navajanardhana Parijatam and a group dance of the warrior clans of the 11th century, in Perini Shivatandavam--were engaging and entertaining in different ways. Hari Krishnan’s choreography of Uma began strikingly as the audience watched six figures in black, one in a tasteful black sari and veil, both with shimmering gold design, making their way down the aisle towards the stage at Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. First, they stepped in front of the curtain, then as the curtain lifted, the male dancer, N. Srikanth in stree vesham, took the center as the other six sat three on each side facing center stage in a unique arrangement characteristic of choreographer Krishnan’s creative use of space. Srikanth is an award-winning Bharatanatyam dancer specializing in performing female roles, and a trained actor who has performed in the Bhagvata Mela dance drama of Melattur, Tamilnadu.  N. Srikanth  Vaaraki, Hari Krishnan, Nagaraj Two singers, Subhiskha Rangarajan and Vaaraki Wijayaraj, amazing Carnatic vocalists from Canada (who sounded like they had just walked in from their homes in Mylapore or Adyar), faced one another as their soulful sounds reached the audience from two sides, along with flautist Nataraj on one side, and mridangam player Nagaraj on the other, with Krishnan in the center of one row as the energetic nattuvanar. An additional touch, characteristic of Krishnan’s thought-provocative choreography was to include Apsara Reddy, seated across from Krishnan on stage, a Chennai based transgender woman, now a successful TV host for the show Natpudan Apsara, to read the English translation of the song. The presentation had very original costume design by the talented Rex, evocative lighting design by Victor Paulraj, and research/translations by Davesh Soneji. Chennai rasikas were fortunate to enjoy this work Uma, commissioned originally in 2006 by the Can Asian International Dance Festival, premiering in Toronto as part of the Gender Transformations Festival that featured cross-gender dance traditions from around the world. Uma was created by Krishnan as a contemporary tribute to the tradition of stree vesham, female impersonation in South India. Krishnan’s many contemporary Bharatanatyam based choreographies, like Uma raises compelling questions about narrow and normative definitions of gender and sexuality, and celebrates multiplicity of identities away from limiting definitions of male and female roles, of sexuality, as indeed of other categories such as nation. In Uma, with his signature playful seriousness, Krishnan deconstructs many aspects of the javali. He plays creatively (as noted in the program) with both traditional and contemporary notions of woman, “as virgin, vamp, lover, mother, wife, mistress, celluloid goddess diva and temple Goddess Devi.” His choreography subtly dramatizes the many dimensions of “the diva and the Devi” rendered exquisitely, with technical rigor and subtle charm by the male dancer. The transformation was complete as Srikanth’s aura and expression convincingly conveyed a delicate yet strong, coy yet defiant female, playing with a long braid, holding the audience spellbound. This use of stree vesham raised questions about the external accouterments that “make” a man or woman recognized as such in society, and the inner energies of male and female that we all have and that can be accessed and performed. Stree vesham, where a man impersonates a woman is found in other performance traditions - for instance, in contemporary Asian American dramatist David Henry Hwang’s Tony award winning drama, M. Butterfly. Here, an elaborate disguise of a Chinese man as a woman named Song is maintained throughout until the dramatic conclusion. His male French lover, Gallimard’s acceptance of Song as his female mistress lies in Orientalist stereotypes of East and West, man and woman, homosexual and heterosexual. Hwang connects the sexual stereotypes to those of national identity. Hence, for the European Gallimard, his Chinese lover Song whom he believes to be a woman was entirely satisfying because s/he knew how to give him pleasure. Song fulfilled all of Gallimard’s fantasies of possessing an “oriental” mistress. This worked also because as explained by Song himself, as an “Oriental,” the West could never accept him as a man. Like Song, Asian men were feminized and this notion of a docile, submissive female was projected from a gender stereotype to national and regional notions of the East manufactured by the West. Hence, sexual notions of the Westerner as masculine and powerful contrast to the Orient as passive, and female, including feminized Asian men. Hwang plays with sexual and gender identity as layered, nuanced and fluid. Song’s male gay sexual identity can take on the qualities of being female, and Gallimard’s heterosexual maleness is quite likely in denial about his own gay desires - after all, he was the lover of the man Song who dressed as a woman. Hwang challenges the narrow limits of male and female, homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual identities; rather, M. Butterfly pushes rigid boundaries among narrow sexual definitions and among limiting stereotypes of East and West  Parshwanath Upadhye  Kalakrishna The evening’s second performance, Purushaardham by Parshwanath Upadhye was remarkable both for his striking combination of tandava energy with gentle lasya grace. His dancing demonstrated high technical virtuosity in movement along with a fluidity, precision, and beautiful expression.Upadhye, trained in Bharatanatyam under Kiran Subramanyam and Sandhya Kiran, is also accomplished in karate (black belt). Apart from his talented dancing, Upadhye is trained as a Carnatic vocalist, and holds an MA in Kannada Literature from Karnataka University. He is the winner of several national awards. Upadhye was followed by Hyderabad’s Kalakrishna who specializes in Kuchipudi, Andhra Natyam and other temple dance traditions of Andhra under Guru Nataraja Ramakrishna. Kalakrishna is an award-recipient from Andhra Pradesh State and national awards such the Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar (2009). Kalakrishna’s rendition of the temple dance Navajanardhana Parijatam in stree vesham re-creates this style performed in temples and courts by dedicated female artists. Kalakrishna is renowned for playing the lasya role along with effective footwork and abhinaya. Kalakrishna’s costume was that of a typical female dancer and externally the costume rendered him a woman. His style of dance at times came across as rather stiff though the entire rendition was powerful.  Pt. Birju Maharaj  Utpal Ghoshal, Pt Birju Maharaj, Anirbhan Bhattacharya The evening performances concluded with maestro Pandit Birju Maharaj’s incredibly nuanced Baithak Bhav. This style of conveying thumris requires the performer to sit and convey the meaning of the songs via his torso, arms, and face. Without footwork, the entire concentration is on the rendition of the bhava. As the line of poetry repeats, Maharaj’s high caliber artistry conveyed each word of the poem that came to life via his eyes and his absolutely captivating singing. The all-encompassing training in the performing arts of that generation who know the music from the core is apparent in Maharaj’s acumen in conveying the narrative and the emotion with clarity, deep involvement, and bhakti. His singing contains profound bhava. Maharaj also displays his own unique wit and humor in abundance - for instance, his recreation in bols and talam of the phone ringing in 10 beats, and repeating until the phone is answered with “hello.” At another point he spontaneously wove into his abhinaya the microphone that was hindering his arm movements. He gazed at it angrily questioning its metallic presence before him when in fact it was Krishna that he was imagining before his eyes! Maharaj commented that bhava must be captured first in voice; only later will it emerge in movement. He shared some charming stories of his own childhood, along with explaining the intricacies of rhythmic patterns. He asserted that there is rhythm in everything and certainly in bols. The artist needs to study how bols move rhythmically up and down. The rhythmic structure creates images and scenarios that are performed such as a street, or the ocean dancing, or the air, leaves and flowers dancing. One can say everything is rhythm and “rhythm is God . . . I learn from nature and its rhythms” commented Maharaj as he presented in abhinaya a bird bringing food to its baby birds. He portrayed Krishna and Radha on a swing, moving languorously, enjoying the rain drenching their faces and hair. The peacocks begin to dance in this environment filled with love and beauty. Maharaj’s sense of joy, his child-like charm, and his gift in creating characters as if fully embodied in front of his eyes were profoundly captivating. In conclusion, the issue of what makes a man or a woman was a compelling part of the entire evening: one dimension is strictly external, namely the clothing and accouterments that “make” a man or woman in society, giving them each a gender identity. However, we all transgress boundaries and express inner energies of male and female that can be accessed in performance as in life. After all, the balancing of these energies is as crucial in creating harmony inside the body as in society and in nature, and equally in the community of living beings. Dr. Ketu H Katrak is Professor of Drama, University of California, Irvine. |