|

|

|

|

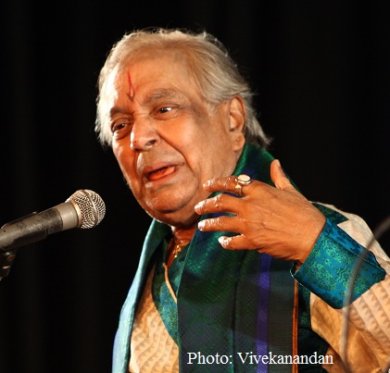

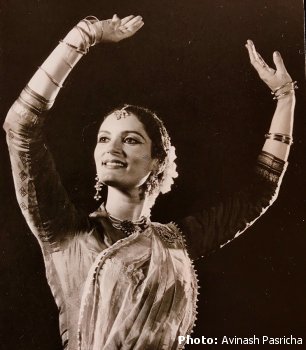

Reflections on the imaginative genius of Pandit Birju Maharaj - Laurie Eisler February 25, 2022 The imagination is what defines space - it dictates and helps project the kind of presence which says 'I am here, take notice.' Imagination enlivens space and makes it tangible, more visible, through the force of a dancer's concentration and focus. The imagination establishes communication, and activates kinetic energy, charging the audience. That's what dance is about - this is the common point - this is what is most primal. - Murray Louis, contemporary dancer, International Dance Festival, New Delhi 1990. The legend, the "Emperor of Kathak", Pandit Birju Maharaj, ascended to the abode of the Devas on January 17, 2022. In the wake of this tremendous loss, social media platforms have been flooded with tributes, live performances, and panel discussions. An eight hour memorial service was held on his birthday anniversary (February 4th) at Kalashram, his teaching institute in New Delhi. Maharaji is acclaimed for his talents not only as a dancer and teacher, but as a choreographer, vocalist, percussionist, instrumentalist, composer, painter, and poet. He was remembered most fondly for his charm, childlike wonder, humor, and lively imagination. It was this quality of imagination that audiences and students of all ages and nationalities reminisce about with such affection. They delight in his keen observations of nature, animals, and people, from which he would improvise spontaneous and often humorous parodies. (For example, a bird's call would inspire him to create a rhythmic tihai. Or he'd see two friends walking, with one versus two hair braids, and would imitate how that changed their gaits.) Maharaji created clever explanations of tihai-s which he could rely on repeatedly as classic crowd pleasers, such as an argument between a lazy and an active friend; a hen with her chicks trailing behind her; the different gaits of a cow, deer, and lion; children playing with a ball, etc. An onomapoeic paramilu tukra (taga naga tari kuku taktak) which imitates the sounds of a frog, cuckoo, and cricket, or alternatively, the journey of a river. Audiences of all ages thrilled to his spectacular gat-bhav of a peacock, joyously dancing in the rain. These descriptive images made his performance accessible, and established a special rapport with audiences worldwide. Not surprisingly, Maharaji integrated his use of imagery into his teaching methods as well. As a former student at the Kathak Kendra, I can personally speak to this. I had the great privilege of enrolling in Pandit Durga Lal's class from 1986-87, and then Maharaji's daily group classes from 1987-1990. His passing rekindled memories, and the desire to explore more deeply this theme of the imagination. There's no question that Maharaji had god given gifts which he developed to an extraordinary degree. Yet, what exists in the heritage of Kathak itself which serves as a historical precedent for his genius?  Farmaishi: From mehfil to proscenium Birju Maharaj grew up in a family lineage of Kathak masters, immersed in the intimate environments in which Kathak flourished, before Independence in 1947. These settings were called mehfil-s, and consisted of court darbar-s, private homes, and in the (now marginalized and denigrated) courtesan or tawaif quarters. The audiences were small, and usually formed of art connoisseurs. We see these contexts depicted in films (some choreographed by Maharaji himself) such as Janak Janak Payal Bhaje, Moghul-i-Azam, Umrao Jaan, Devdas, Bajirao Mastani, and more. A crucial ingredient in these mehfil-s was the tradition of farmaishi. This Urdu term translates as a "request", wherein an audience member requested of a performer a specific item, be it a chakradar tihai, gat, tukra, thumri, a certain raga, etc. The audience or patron could literally shape the course of a performance by requesting certain items as a farmaishi. Performers actively interacted with their audience. In this era, the patronage of the courts in North India fostered a lively cultural interchange, and invited friendly competitions between Kathak dancers. This supportive environment drove performers to excel technically, and to create new compositions as entertainment for their patrons (some of whom, like Wajid Ali Shah in Lucknow were composers and lyricists themselves). Within the court setting, the tradition of solo tabla performances also strove to entertain, featuring short compositions named after their character. These short rhythmic passages would often imitate nature (pigeons, deer, galloping horses, etc.). The introduction of the railway became the popular showpiece called a rela (though another interpretation of the word is literally a "rush" like a river). Since the tabla is the mainstay of Kathak accompaniment, it's not surprising that there would be an exchange of these analogies. Varieties of the rela are common to Kathak footwork to this day. Any audience member emotionally overcome by the artistic excellence of the performer could at any point exclaim appreciative praises and compliments, referred to as "tareef karna" (e.g. the well-known "kya baat hain"). Their praise would encourage and spark artists to reach greater heights of inspiration. Often there would be a special patron, sitting front center, to whom the performer would give acknowledgment (salaam). In Post-Independence India, when teaching institutions were created by the new government as a means to promote the arts, larger auditoriums were built which dramatically changed the intimate dynamic of audience participation. As in Western symphony halls, the proscenium halls expect audiences to remain silent until the finale. Maharaji started teaching at one of these institutions in New Delhi, the Bharatiya Kala Kendra, when he was just fourteen. He began choreographing dance-dramas for companies of dancers on larger stages such as the nearby Kamani Auditorium. Naturally, in this setting, the tradition of audience interaction through farmaishi waned. And although the solo tradition also continued, it became more difficult for a lone dancer on a huge stage to engage the audience in the same way. So how did Maharaji manage to spellbind large audiences of all ages and nationalities, many of whom had never seen Kathak before, in these contexts? How did he create as intimate an atmosphere in Carnegie Hall as would occur in a private party with only tabla and sarangi as accompaniment? Here we come to Maharaji's genius. I submit that he intuitively drew on his roots, based in this ethos of farmaishi, yet he expanded and refined the tradition to adapt to new environments. His flexibility reflected the openness of the genre of Kathak itself, which allows for constant revision and innovation within traditional parameters. Improvisation, the very heart of Kathak, spurs the imagination to adapt to the moment, and it is this quality which is most prized in performance. Thus it was natural for Maharaji to intuitively respond to the particular audience in front of him, no matter what the demographics were. For instance, in an Asia TV tribute, dancer Aditi Mangaldas reminisced about how, in New York's Lincoln Center, Maharaji peeked at the audience from backstage, and accordingly made last minute edits just moments before the company went onstage. Or, as his student and concert presenter in the U.S., Rita Mustafi mentioned in a Narthaki tribute panel, he'd spontaneously improvise a tihai inspired by a cough in the audience, or acknowledge a baby's cry with "Haan, beta?", drawing laughter. Maharaji rolled with the times. In 2012 at NY's Symphony Space, he spun a rhythmic tale of tapping on a cell phone, getting a busy signal, dialing several more times, then picking up with a "Hallo?" And as a nod to the mehfils of old, often the first few rows of the audience would be lit, so that he could connect visually with other renowned artistes and rasikas, who had a more sophisticated grasp of the nuances of the form. As we have seen, Maharaji had a gift of connecting with his audiences through humor and colorful images. How did this manifest in his approach to teaching?  Photo: Laurie Eisler Creative imagery in teaching: Making connections Maharaji was known by his students for his patience, humor, affection, and most of all for his detailed explanations of the technique and feeling of Kathak through the use of mythological stories and philosophy, socio-cultural references, and most of all, his expansive range of imaginative analogies, or images. The classroom allowed for even greater freedom of imagination than the pressures of the stage. When a dancer visualizes a specific image while performing a movement, its quality and feeling tone immediately transforms. Imagine spinning into a "sam" (a final pose, freeze-framed) while picturing gently placing a flower with a hand gesture. There is eye-hand connection as well as a bhava or expressive feeling, of delicacy, love, beauty. It is a mindful, intentional gesture. Another image Maharaji suggested while teaching the slow introductory Amad, was to think of strumming an instrument like the veena when stretching the arm back in a high diagonal, with a subtle flick of the fingers. Immediately there was a specific focal point, creating a link and making the movement precise, light and quick. Or to convey the gait of a village maiden carrying a water vessel on her head in Panihari gat (unfamiliar to city dwellers), he would have students try walking with a book on their heads, and then carry the image of the added weight in their minds as they danced. The use of imagery enhances what Maharaji called "involvement". This may be what the ancient Sanskrit text Abhinaya Darpana famously describes in the oft-quoted, "Where the hand goes, the gaze follows; where the eyes are, the mind follows; where the mind goes, bhava follows; and where there is bhava, there is rasa". It is a presence, an inner-directed focus, an integration of mind and body. In the martial art form of Kerala, Kalaripayattu, there is an expression: "The body becomes an eye", meaning every cell in the body is awake and mindful. Maharaji embodied this, and strove to convey it in various ways to his students. He'd say, "At any moment while dancing, if you stop, that pose should have beauty of ang (lines, alignment), like a freeze-frame photograph". He'd suggest, while dancing Natawari tukras with slow spins, "Imagine showing off a jeweled belt, with a diamond at the hip. When one wears new jewelry, one moves the head and neck differently and is conscious of beauty." There are countless examples of the idea of 'connectivity', often infused with a love for the body as a temple of beauty. Many of Maharaji's instructions linked different body parts, from the feet up. He'd speak of how he loved his feet, and when performing footwork, would imagine massaging the earth. When striking a pose looking down, "the nose should connect with the big toe". Or, when depicting shyness during bait ke bhav (seated), he'd point out how first his foot would draw inwards towards the safe cover of his lap-shawl, and then he'd avert his eyes modestly under the ghungat (veil). The gesture started with the foot. Another example of his use of the term "involvement" had to do with the engagement of intrinsic core muscles in the torso. He would show his students his back, which was astonishingly toned and articulated with muscles most people wouldn't be aware existed. His approach wasn't about flinging the limbs about like a windmill. Instead, movements were initiated from the core, from the chest, from the heart. Maharaji communicated this inner directed focus through many varied images. Since the sam is so infinitely crucial to Kathak, he'd describe how to increase its impact by first drawing the hands in towards one's center while contracting in the torso, and then "springing out", extending like a bow and arrow, or with a string between the hands, arriving precisely on the final beat. The effect was striking and powerful. Spiritual content On the occasion of Saraswati Puja, in a moving speech to his young students at Kalashram, Saswati Sen advised them to remember the loving manner of his teaching. She emphasized the depth of his teachings, the deep well of his spiritual wisdom. Much of the images Maharaji would share in the classroom were of a philosophical and spiritual nature. For instance, when describing the union of polarities in the male/female Ardhanarishwara (Shiva and Parvati) item, he'd draw the analogy in movement of tandava and lasya, force and softness, hero-heroine, saying, "You don't have to go outside of yourself. They meet in the movement". On a similar note, he drew on Hindu mythology to demonstrate how to "collect" one's vital energy and maintain the central axis while performing spins: in a contest between Ganesh and his brother Subramania for who could circle the universe faster, Subramania took off on his peacock, while Ganesh decided to take a turn around his parents, thus winning. The universe is contained within ourselves. Perhaps the most indelible impression, for me, remains a teaching moment during the subtle introspective sequence called thaat: "The facial expression will come naturally if you think of your body as an oil lamp. The dipa is at your heart, the wick arises from there, the flame lights up your facial expression with its flickering, and subtly moves the neck, lips, eyes, and eyebrows. Do not exaggerate the movement, because then the lantern will shake, and the flame will go out". Maharaji's flame will never go out. It is lit for eternity, carried forward in the legacy he has gifted to thousands of his students and to the world. Acknowledgments: Much gratitude to American Institute for Indian Studies for supporting my studies with grants from the Smithsonian; to Shubha Chauduri at the Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology, Delhi; Deepti Gupta for video transcriptions; Tributes panel on ICAN GOVERN Insights 46; Tributes in the February 2022 Narthaki newsletter; articles by Navina Jafa in The Wire, Indian Express and elsewhere; discussions with Ustad Zakir Hussain, Navina Jafa, Miriam Phillips, Veronique Azan, and many more!  Photo: Avinash Pasricha Laurie Eisler can be contacted on Facebook or at laurieeisler@gmail.com Responses * What an amazing, insightful and heartfelt tribute! (March 3, 2022) Post your comments Please provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |