|

|

|

|

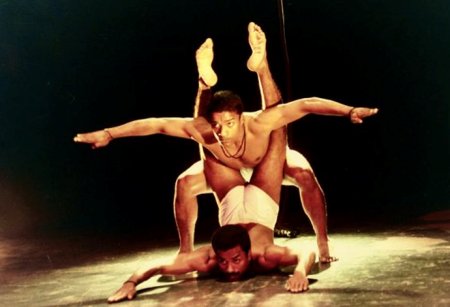

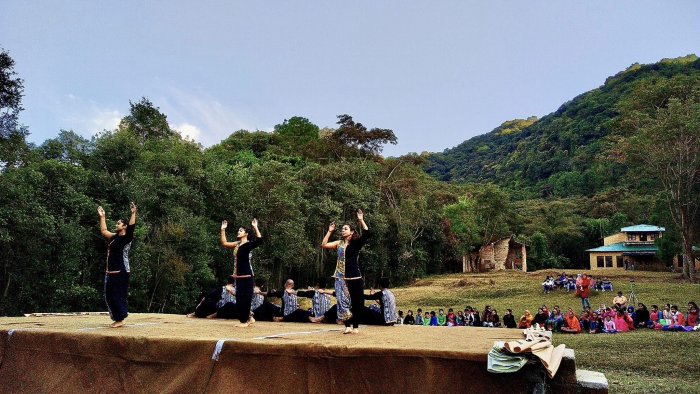

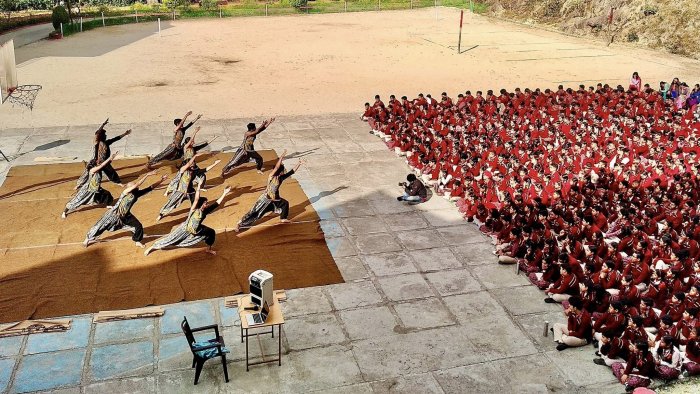

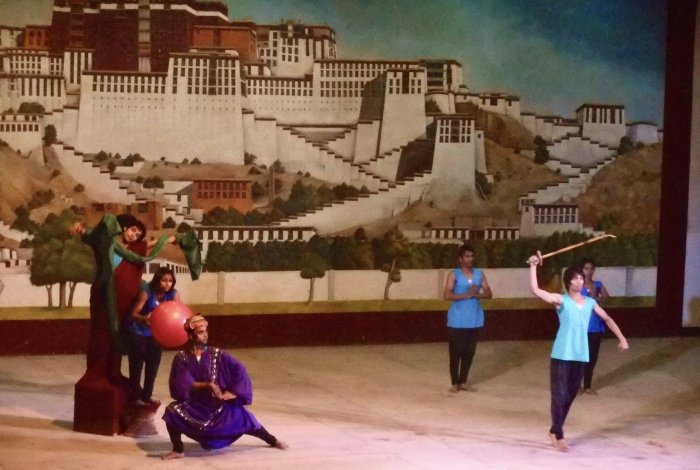

CHAALI... taking dance to her audience - Bharat Sharma e-mail: bhasha.dance @gmail.com From Narendra Sharma Archive December 12, 2024 Performance thrives in Live Performance - this is fundamental to any Intangible Art. At a fundamental level, it is a conversation between the Body and the Viewer in a defined space of culture. This is primal, if we take stick figures etched in Bhimbetka Caves near Bhojpur in Madhya Pradesh as manifestation of community and participatory exuberance, or sophisticated articulation of an individual's craft of the sharira to the rasika, as expounded in the rasa theory in the Natyashastra (5th century BC). From time immemorial, the relationship between dance and her audience has been crucial for the survival of oral traditions. Dance as Live Performance is also linked to life cycle of humans - dance is lived while the body has breath. Dance gets activated at birth and dies at death, leaving traces in memory of viewers, or remembered through traditions passed on by generational lineages. These memories of the dancing body are affirmations of the ethereal nature of performance. Dance can be kept alive, in Time and Space, through a system that brings together the dancing body and the viewer to converse. These eco-systems of performance can then be termed as support system within a culture. In modern times of a globalized world, the relationship of performance and audience across cultural contours has become tenuous and complex. The performance memory of an Individual has become more crowded due to media overreach provided by communication technology. Overloaded with information, the eyes are bombarded with images every day in 2-dimensional avatar, on the mobile phones we carry in our hands. Film industry has further squeezed the space of performance by its 'online presence' - we do not feel the necessity anymore to make an effort to go to a theatre, to see dance. At the cusp of India's Independence, there was much talk on the patronage system for the performing arts - of the princely states, the community support, private philanthropy and new state agencies of the emergent nation. Some ideas foregrounded were - Hindustani music supported by the princely States in north India; temples supporting classical dance forms in the south; Parsi theatre in the west and Jatra in the east, attempting to make a profession out of theatre; folk dances attracting community support; popular dance drawing sustenance from film industry; 'voluntary support' to new performance manifestations; and so on... However, there were gaps in addressing issues of expanding performance opportunities in the public domain and developing systems to generate income through performance. The state was found cautious in entering the realm of organized support for live performance, as traditions were sought to be discovered in nooks and corners of the country. All cultural thinkers in 20th century acknowledged the staggering diversity of art forms in South Asia, in terms of languages, story-telling traditions, expressive forms and artistic practices. Urbanization, as a legacy of colonial pasts, saw fragile middle class pitted against the historically rooted caste system in the countryside. Given these anxious promises of freedom, India's modernity had to negotiate all this, and much more. As a choreographer and dancer, one was lucky to witness momentous happenings in the formative years of nation building in the capital. Born in the 50s, my parents provided the bridge over events before and after Independence. As much as Delhi became a center of power, the peripheries had their own tensions and pulls, akin to a bicycle-tire having a hub and spoke. As ideas were absorbed by the center, the power also disseminated to the periphery in myriad colors. My father Narendra Sharma was a student of Uday Shankar at his seminal center of creativity in performing arts, established in inter-war years at Almora, Uttarakhand (1939-43) in the foothills of mighty Himalayas. This unique school trained a generation of artists that left behind lasting contributions in their respective disciplines. My father stuck to dance following his training in choreography, and after a meandering and tumultuous career in Kolkata and Mumbai, he settled in Delhi in 1954. In Mumbai, he married Jayanti, a migrant who fled from Karachi after the Partition, and she became a singer, dancer and costume designer to her husband's prolific artistic journey. I was in my mother's womb, like Mahabharat's Abhimanyu, when my father began conceiving a massive spectacle based on Tulsidas's Ramcharitmanas - an epic dance-theatre condensed in 3 hours - from Ram's childbirth till his coronation in Ayodhya. Mounted at Ferozeshah Kotla Stadium, the press acclaimed this choreography as the first big post-independent production, that too by a professional group supported by a corporate entity - DCM. This production is still performed on every Dushehra in Delhi, becoming an essential feature of annual cultural calendar of the capital. This Ramlila was launched in 1957. The very next year, in 1958, Sangeet Natak Akademi (SNA) organized National Seminar on Dance which became a benchmark for next few decades in shaping interventions by state agencies. I recently re-read the two volumes printed by the SNA in 2013, edited by Dr. Sunil Kothari. This reading in retrospect, gave fascinating insights on the full-range of thinking process of pioneers, scholars and dancers, at the dawn of Independence. I realized a whole range of contemporary issues were already sorted out, and articulated succinctly by some of the finest minds of the times. My formal entry in performing arts was in 70s when my father setup Bhoomika Creative Dance Center as an independent dance company, which celebrated 50th year of founding in 2022. By the time I finished college in 1977, I had already earned a place and name for myself as dancer in innovative choreographies of my father. Athletic and young blooded, there was always a thrill to be on stage, of being appreciated and critiqued. The sweat that flowed from every cell of my body after each performance reaffirmed a profound sense of liberation and life affirming values. However, given the kind of dances Bhoomika presented, opportunities were far and few, despite attracting sufficient critical acclaim each time the group appeared on stage. These gaps, between performance and lack of opportunity, were deeply painful. And this angst continued to bite inside my sinews and psyche for the rest of my career. Years of practice for path-breaking new ballets would end up in handful of performances. I wanted to dance, and pursue a career as live performer, for all its worth. One craved to be on stage, and the denial became frustrating as time passed by. And soon I came to know I was not alone in this state of being. In the 90s, I moved out of Delhi to seek answers for myself, and this journey took a turn towards the South of India... I went to Bhopal and tried my hand at acting. That helped me to still keep moving on stage, in theatre, if not in dance. Thereafter, in 1993, I moved deeper southwards... I joined the first team of India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) as Programme Director in Bengaluru, to setup a private grant-making agency, based on the philosophy of philanthropy. This was a learning experience. After being on one side of the table, as grant-seeker, I found myself planted on the other side of the table - as grant-maker. Performing arts in India altogether looked different thereafter. As I conversed with practitioners and witnessed whole range of art activity across disciplines, issues looked more intriguing. Fund-raising from the corporate sector and grant-making in the arts had different set of issues. Proposals received through a transparent public process revealed an underlying mindset in the arts field which was more obsessed with preserving the past than to grapple with issues of the present. Dance world was found to have special problems, needing separate attention. However, Bengaluru was quite an open city, having a liberal and receptive outlook to new approaches in choreography. After networking artistic groups, press, intellectuals, foreign agencies and NGOs in the city, within a decade, the city began attracting practitioners from India and abroad, with an appreciative and stable audience presence in auditoriums. City became a hub, if not the spoke, of contemporary dance in the South. There was constant refrain from dancers of lack of opportunity to perform consistently, and I could feel from within, their pain. This was across all genres of concert dancing - classical, modern, dance-drama, ballet etc. One classical dancer confessed privately that she had stopped teaching as her students became emotional wrecks after years of training, as they were unable to perform on stage either as soloists or by ending up sporadically in chorus groups behind prima donnas. In non-classical formats, situation was even worse. Theoretically, good performers or productions should get the natural life span on stage, to mature or thrive in the public domain before winding up. At another level, on ground, most performances were limited to personalized social gatherings in urban areas and metropolis, with little access into community spaces of semi-urban/village outlets. In any case, there was no professional systems for dance anywhere in the country to talk about. My urge to dance, and to be a hands-on activist, remained sublimated for long. Table job looked restrictive at times, and I decided to quit to get back to the field. This time I preferred to enter a domain that remained unaddressed at fundamental level in performing arts - of developing support systems for dance to expand opportunities, especially innovative choreography. As a stepping out grant from IFA, I decided to work in this critical area. To begin with, I looked for possible models to emulate. In theatre there were many - NINASAM's Tirugata in Karnataka; Jatra in Assam, Bengal and Orissa; theatre circuits in Maharashtra were sustainable and successful, but all operated within their specific linguistic milieu like Kannada, Marathi, Bengali, Oriya... Outside India, I had observed the remarkable model of Riksteatern (National Touring Theatre) based outside Gotemburg, as a guest of Swedish Institute in 1992. An entire institution with dedicated infrastructure was built through state support, to help produce dance and theatre productions that could travel for months and years, on dedicated trails of organized performance circuits - on highways, in buses - connecting scores of theatres, performance spaces and venues across Sweden. Dance had the advantage to cut across linguistic barriers within a region. I was reminded of a tested model to emulate in India. Sachin Shankar was a classmate of my father at Uday Shankar's Almora School. The duo setup a partnership 'Sachin Sharma' in Mumbai to choreograph 'song-and-dance' sequences in commercial films, only to earn and spend on their dance group New Stage in 40s. They split before my father re-located to Delhi, but Sachin Shankar's Ballet Unit flourished in Mumbai. In 70s and 80s, Ballet Unit bought a Tata mini-bus that could carry basic equipment of lights, sound and artists. Ballet Unit toured for months across India giving performances in nooks and corners. Sachin Shankar wrote an article in twin-volume of SNA's Seminar of Dance in 1958 referred above. He termed his dance as 'Modern Ballet'. In a personal interview, he told me the reasons to buy the mini-bus - when the group was not performing, he would rent out the bus to tour operators to earn income. For performance tours, he gave another example of his successful intervention. He used to book a year in advance, an auditorium in thickly populated central Kolkata for a month. There his dance productions were assured of ticketed and sold-out performances. Before and after this season in Kolkata each year, he used to tie-up with series of venues to give performances enroute and back, between Mumbai and Kolkata, traveling in the mini-bus with artists and equipment. In the process, he found ways to break even the expenditure on these performance-circuits, and made profit at times. With these models in mind, I embarked on a 9-month research project in 1999 and travelled the culturally fertile coastal region of the South along western coast and ghats from Goa down to Kerala. Peninsular India was found to be politically stable, and art groups were plenty, in smaller towns and villages, doing exemplary work within diverse communities. Several had captive audience bases, modest theatre and dance infrastructure, requisite intellectual tradition for participatory action, and latent cultural economy to support the arts. It took time to find partners, but meeting people personally on their home turf had its own benefit. One link led to another. Much travel happened on public transport to meet and converse with a range of potential organizers, art groups, NGOs, educational institutions, tourist outlets and individuals. Field research included an analysis of audience perceptions across regional, linguistic/cultural and urban/rural boundaries; survey of repertoires of dance groups in India; networking individuals and organizations to host residencies; evolving strategies to access audiences; and planning logistics in terms of performance venues, stay and food. As the performance network evolved in a positive frame, need was felt to have a name for the project to facilitate easier communication. Chaali is a term that is found quite often in traditional performance terminology. I took recourse to my training in Mayurbhanj Chhau of Orissa, where Chaali as a term described the first series of 6 stylized walks. These leg-gestures were special as they were rendered by walking constantly from one point in space to another. Chaali then became the metaphor behind the project - of extending the space of dancers through travel on highways and roads to reach audience, from one venue to another. Yet again, as against the dominant industry of Sports, performance circuit of dance was given a feminine persona - '... taking dance to her audience.'  In Anantpur, Andhra Pradesh Round I, of almost 40 days, was undertaken between January 24 and March 5, 2001 by a 10-member nationally and internationally acclaimed dancers/groups, and covered approximately 5000 kilometers that travelled along the coastal corridor of Goa, Karnataka, Kerala, and through Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. The 37-event circuit (with 18 performances and 19 workshops/lecture-demonstrations) traversed national, state highways and narrow roads, and passed through metropolitan cities, state capitals, small towns and villages. In Round II, 15-member acclaimed dancers/groups again ventured forth between November 10 till December 22, 2002 to hold residencies, performances and workshops, traversing a similar route through the states for a 40-day and 41-event circuit (31 performances and 18 workshops / interactive sessions). The group this time travelled more than 6000 kilometers. Performances were mounted in varied spaces - well-equipped theatres, open air spaces, black boxes, makeshift stages, studios, art galleries and tourist complexes. Light and sound equipment was carried in Tempo Traveler/Swaraj Mazda mini-bus that maintained basic standard of aesthetics of presentations. On a typical day, the group would arrive in a town/village to give a workshop in morning, set up the stage in afternoon, perform, dismantle, pack up and rest, only to move to the next destination the following day. Over 18,000 people as audience were accessed in two rounds. A network of individuals and organizations in local settings made admirable efforts to host residencies and present choreographic works. Workshops and lecture-demonstrations played a crucial role in furthering goals of project. It fostered dialogue with local artists (with theatre groups and dancers), addressed issues related to work of voluntary organizations (working with people with disabilities, street children and NGOs) and gave inputs to local dancers on varied techniques (traditional styles, improvisation and composition). These performance circuits got substantive and impressive coverage from media, especially the vernacular press.  Samudra, in Chennai, Tamil Nadu There were other facets in the two rounds which need separate mention. One tended to avoid state capitals (like Bengaluru, Chennai and Hyderabad) as that required large budgets and influential local sponsors. But to our rescue came the network of Alliance Francaise who had compact auditoriums in most state capitals. All came forward to offer their venues for free. In Goa, we had a resourceful partner in Crisologo Furtado, a painter, who had solid grasp of opportunities available in the state. In both rounds, he took the entire responsibility of networking and worked out a model where the performances/workshops paid for itself.  In Margao, Goa Chaali took care of all costs of travel by rail and road for the artists, to and from their home, plus a decent and assured consolidated fee for the entire engagement with the project. The aim was to provide artists a large volume of performance opportunities within a short span. For the hosts, Chaali took responsibility to enter each town/village, taking care of stay and food. Local groups were responsible for presentations, audience presence and public outreach. Some groups had ticketed shows, and the money went back to the groups who organized the event. These two rounds were supported by IFA, Bengaluru and BSA Cycles, Chennai along with a network of art groups, NGOs, schools, institutions and individuals. In first round, 40% of total expenditure was recovered through performance fees and other means, and in second round this proportion got better to 60% of the total budget. Given the enthusiasm of hosts, there was every reason to build upon this cultural economy in future. Dance groups who travelled in both rounds included Samudra from Thiruvananthapuram who toured with their acclaimed productions - 'Jalam' and 'Sound of Silence'. From Kolkata came Dancer's Guild who brought excerpts of choreography of Manjushri Chaki Sircar and Ranjabati Sircar. From Bengaluru, Bhoorang travelled with works from Bharat Sharma and Tripura Kashyap including 'Jatakmala' and '100 Footsteps'. Equipment and technicians were provided by theatre group Koothu-P-Pattarai from Chennai. The last performance of the second round in University of Hyderabad campus had an impact, which opened up yet another avenue. Sarojini Naidu School of Arts of the University offered me a post of Associate Professor, Dance and I soon shifted base to teach at the university. There I tried in vain to gift the entire Chaali project to the arts school, making an argument that such a network could be useful as an innovative educational tool for art students to work all over the South in diverse cultural settings. By 2005, Chaali folded up in South India... After the demise of founder-director Narendra Sharma on Makar Sankranti in January 2008 after a brief illness, I re-located to Delhi to work as the new director of Bhoomika in July 2009. My professional upbringing in dance was closely associated with the ebb and flow of the dance company since the 70s, before I quit in 1990. Returning to the capital after a gap of 18 years to reconnect was unsettling. There was no choice but to re-draft the trajectory of Bhoomika altogether in its new contexts. To begin with, the studio in East Delhi where the choreographer worked since 1982, his karma bhoomi, was re-christened NarenJayan Studio, combining the first names of my parents. A new professionally sprung wooden dance floor was laid, with donations from colleagues and the students. This became the new hub for future interventions. Chaali in South India was too valuable an experience to forget. I took that as a fulcrum to explore possibilities in the North. For this another intervention of the founder-director came to rescue. At the time of his demise, he was the President of Woodlands Society, Andretta - a village in Palampur district in Himachal Pradesh - where he had been visiting for long for artistic pursuits. Andretta was developed as a village for art practice by eminent artists like Norah Richards (Theatre), Bhabhesh Sanyal (painter) and Gurcharan Singh (potter). This idyllic village with an expansive view of Dhauladhar Ranges of the mighty Himalayas, often reminded the choreographer of his days at Almora where his dance journey started. He often dreamt of setting a school of choreography in rural settings. Bhabhesh Sanyal, who was then President of both the societies - Woodlands Society and Bhoomika - had invited him in 1975 to pursue the idea, as he himself dreamt of Andretta as an artist collective in natural settings. Andretta was ideally placed in a milieu with a hoary past - within a range of Kangra School of Miniature Painting, and princely families in Kangra City tracing their family lineage to the days of Mahabharat! Norah Richards, the founder of Woodlands Society in Andretta was an Irish lady, who had campaigned for India's freedom in England between the two world wars. She migrated to India from Lahore after the Partition and chose to settle in Kangra Valley. She later taught English literature and drama at Punjabi University, Patiala. A firm believer in rural reconstruction having local roots, close to Tolstoyan perspectives, she donated a part of her estate to the university. Punjabi University has now converted her mud house in the estate into a museum where a small open-air theatre built by her still stands. In early 90s, Amba Sanyal, theatre person and costume designer, and her partner, Prof. K T Ravindran, urban designer and architect, started thinking of constructing an art center in the estate, exploring local materials with organic architectural features. Amba's father, Bhabhesh Sanyal fully endorsed this intervention. After his demise in 2003, Norah Centre for Arts (NCFA)/B C Sanyal Retreat (BCSR) was finally built with support from Ministry of Culture, and matching donations from well-wishers and eminent artists. Given these underlying threads embedded in Bhoomika's history, it was now time for me to translate the experience of Chaali to conditions in North West India. In March 2011, with Bhoomika's dance company as a focal group, my work began by taking NarenJayan Studio in East Delhi, largest parliamentary constituency of Delhi, and NCFA in Kangra Valley, the largest constituency in Himachal Pradesh, as two poles to explore possibilities of setting up a fresh performance circuit connecting the two. I soon began traveling to explore conditions in Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh, Punjab, Haryana and East Delhi, to find partners to network. I found the conditions on ground in these areas at total variance with the ones experienced in the South. To begin with, awareness on dance was problematic. Besides Bhangra and a bit of Kathak, people only talked of Bollywood Dancing. Rich folk traditions, no doubt, were respected and part of people's lifestyles. There was total absence of awareness of Indian Ballet or new choreography outside narrow pockets. There was dearth of 'voluntary groups', of artists or NGOs, who were interested in Bhoomika's new dances. One reached out to officials in state governments who initially were receptive, but not willing to commit anything formally. There was a strong 'insider / outsider' perception that was ingrained in populace, especially in Himachal Pradesh. Despite this difficulty, a two-week performance circuit was knitted together in 2011, starting from Andretta, and winding down to select venues in Chandigarh, Haryana and Delhi. Bhoomika was willing to take some risk from its own savings to initiate this version of Chaali. One week before the tour, most of the venue partners and officials - in Shimla, Chandigarh and Haryana - backed out, although a handful of organizations around Palampur remain committed. The entire tour was shelved, and forced me to return to the drawing board to re-think issues. This time, the 'hub and spoke' idea had to be re-framed. After a gap of one year, Chaali was relaunched by focusing activities in and around NCFA, Andretta. I had by then got elected as Secretary of Woodlands Society. Andretta, by virtue of being traditionally a potter's village and abode for contemporary visual artists in recent times, luckily got declared a Heritage Village by Himachal Government. Members of society strongly advocated working in community on issues of arts, environment protection and climate change, especially related to fragile eco-system within the state.  In Andretta, Himachal Pradesh - Chaali/North India  In Palampur, Himachal Pradesh Bhoomika, being a dance company, had the natural capacity to travel and access audiences in neighboring villages and towns. A decision was taken to circumvent activities within the boundaries of Kangra Valley with Andretta as a core hub. The tract between Dharamshala till Mandi, and the highway connecting two towns, was growing with significant presence of educational institutions, voluntary organizations and tourist complexes. The quality of education in primary and secondary schools, especially government schools in Himachal, had already hit a high on national indexes, almost next to Kerala. Bhoomika had recruited fresh lot of young dancers who were undergoing vigorous training in 2012 at NarenJayan Studio. A fresh phase of training was planned by organizing a two-week intensive residency as Andretta Reyazshala at NCFA from May 5-20, 2012, with a 12-hour daily schedule in Yoga, Mayurbhanj Chhau, Modern Technique, improvisation and composition, discussions and film screenings. With conducive climate, inspiring ambiance, nutritious food and water, dancers felt energized by focused learning in natural environment, outside the crowded and dissipating humdrum of metropolis. Other issues came into play - new dances with fresh themes had to be made for the uninitiated in rural and semi-urban milieu in Kangra. For new themes, one took recourse to literary content generated by Chakmak magazine in Hindi for children, brought out by the influential Eklavya project based in Hoshangabad, Madhya Pradesh. Since Eklavya had done pathbreaking work in People's Science in rural areas, with inputs from Social Scientists, the range of themes were found apt and fertile to be explored in dance. For next rounds of Chaali, Bhoomika took up themes exclusively from stories generated by Chakmak magazine, which in turn brought a qualitative change in choreography. Ground work on new themes and fresh choreography was done in Delhi beforehand, but completed in Andretta. On the concluding day of Reyazshala, an impromptu showing was done for village folk and select group of potential partners from nearby institutions. It was now time to look for partners in the valley to carve out a performance circuit.  In Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh  In Rajol, Himachal Pradesh One contact led to another. First major contact was the Principal of DAV School in Palampur. He turned out to be a boon with whom a major collaboration was built over the next decade, whereby he opened possibilities of performances in a series of DAV schools all over Kangra, with additional teaching assignments in their schools as follow ups through the year. Soon other principals of government schools, colleges and private educational institutions got interested in hosting performances, and NGOs around Dharamshala and Rakkar found value in collaborating. I visited each venue to meet leaders personally and plan logistics. Funding for such a project was a major hurdle. There was absolutely no money locally, private or public, although some provided help in kind. Corporates had little presence, and funds under Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) was a far cry. Luckily, Ministry of Culture at the center had just announced a new grant scheme - Cultural Functions Grant Scheme (CFGS) - which gave flexibility for groups to do innovative projects. Once our application was accepted, a modest grant gave the green signal to begin Chaali in the North. There was another substantive development in terms of collaboration with a women's organization, Jagori Grameen, to align with themes of their choice. They provided series of venues within their network in remote areas of Dharamshala/Sidhbari area that helped Chaali reach government schools and NGOs in remotest areas. To our surprise, some girls in schools were exposed to live performance for the first time in their lives. In Dharamshala, contact made in an earlier round with Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA), helped to reach residential children of Tibetan Schools in Chauntra, Lower Dharamshala and Tashi Jong. Within 8 years, 6 more rounds of performance circuits have been organized in Kangra Valley. Given the mountainous region with winding roads, the strength of the dance company was curtailed to 8-10 members to fit in small Tempo-Traveler/Tata Winger. Since floors for dance were uneven, light-weight dance mat of 30 feet by 25 was always carried to let dancers feel comfortable during performances. Since power supply was erratic, battery-operated speaker system was always carried for uninterrupted presentations. Props and costumes were always meagre, and the setting up of stage took barely 15 minutes. Since the principals preferred to have performances in school hours, 50-minute modules were danced in broad daylight. This efficient, street-theatre kind of format allowed 2-3 performances a day. Audiences varied from 100 to 1000 members in a venue. Series of performances and workshops (about 200) have been hosted by partners whose support has been very consistent. Some are: DAV Schools - Palampur, Hamirpur, Alampur, Bankhandi, Narwana, Dharamshala; Kendriya Vidyalaya - Holta Camp, Alihal, Gohju; Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalaya, Paprola; Tibetan School of Performing Arts (TIPA), McLeodganj; Tibetan Village School, Chauntra, Lower Dharmashala, Tashi Jong; Greenfield School, Nagrota; Chinmaya Organization of Rural Development (CORD), Sidhbari; Aavishkar, Kandbari; H.P. Agricultural University, Palampur; National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT), Kangra; Govt. Senior and Secondary Schools (girls and boys) - Palampur, Kandbari, Saraswa, Hatli, Rajol, Chateharh, Tangroti, Rakkad; CSIR Complex, Palampur; Cambridge School, Palampur; Himachal Central University, Shahpur; and many more... In Round VIII in November 2019, Himachal Government got interested in Chaali for the first time, and included a 10-day (10-performance) circuit in their flagship multi-disciplinary Trigart Cultural Festival all over Kangra Valley. As usual, the response from partners and audience was overwhelming. However, no long-term commitment from the local government has been forthcoming. With erratic funding from outside the state, Chaali is unable to keep active the enthusiastic network alive, to tour on a regular basis. This raises the issue of arts funding for performance in India, in general. Systematic investment from public and private sources is still a pittance. There's still resistance to fund innovative projects in performing arts, especially dance. As such, it will be pertinent to re-asses the recommendations made in Volume 2 of the SNA Seminar on Dance of 1958 - barring seeking support for specific styles, there was no indication whatsoever on future of dance. This promise of Independence still remains unfulfilled. Projects like Chaali are still begging for attention from donors, despite being on the ground for 25 years. Performance thrives in Live Performance, was my original dictum of this paper. In Indian contexts, Chaali was initiated as a research project in 1999, to evolve support systems for dance across regions. This time-tested model is now waiting for takers...  Bharat Sharma's career in dance spanning over five decades is marked by diversity of experiences as performer, choreographer, teacher, writer, composer, film-maker and arts administrator. He currently leads Bhoomika, New Delhi. Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will be featured in the site. |