|

|

|

|

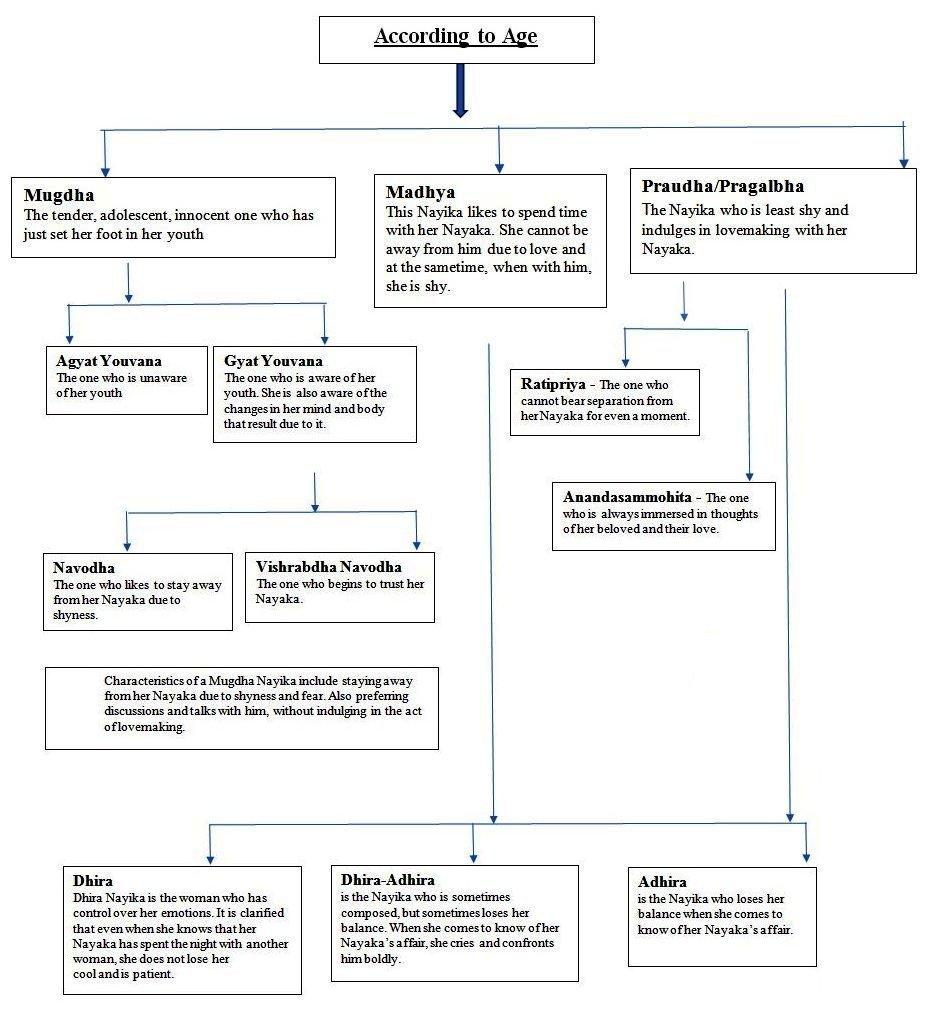

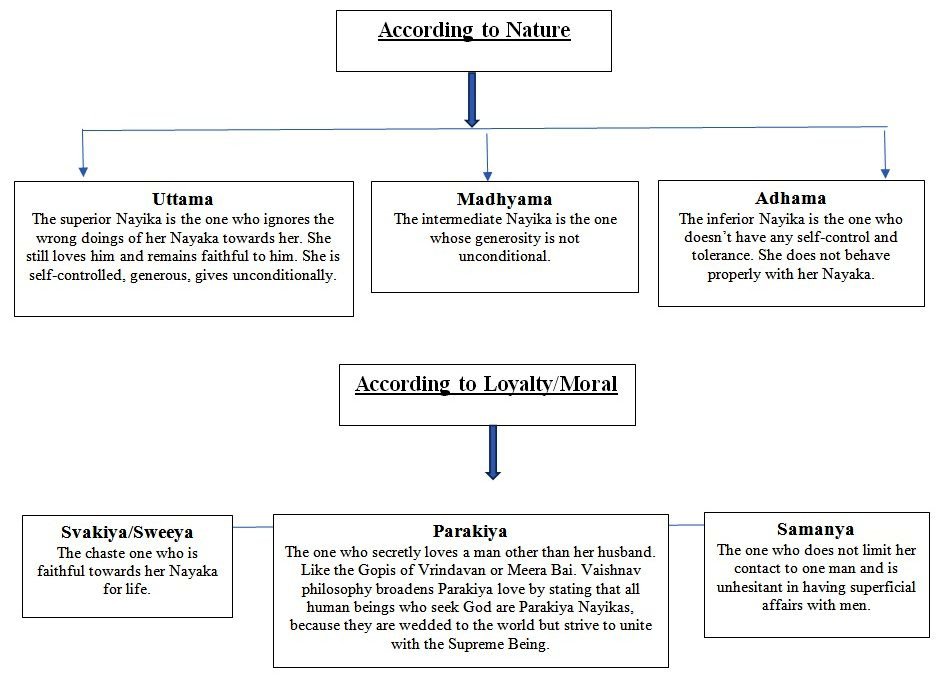

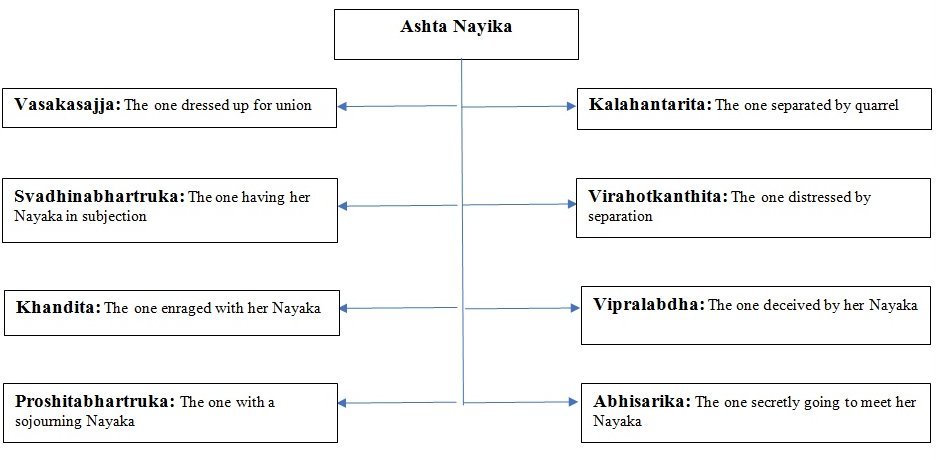

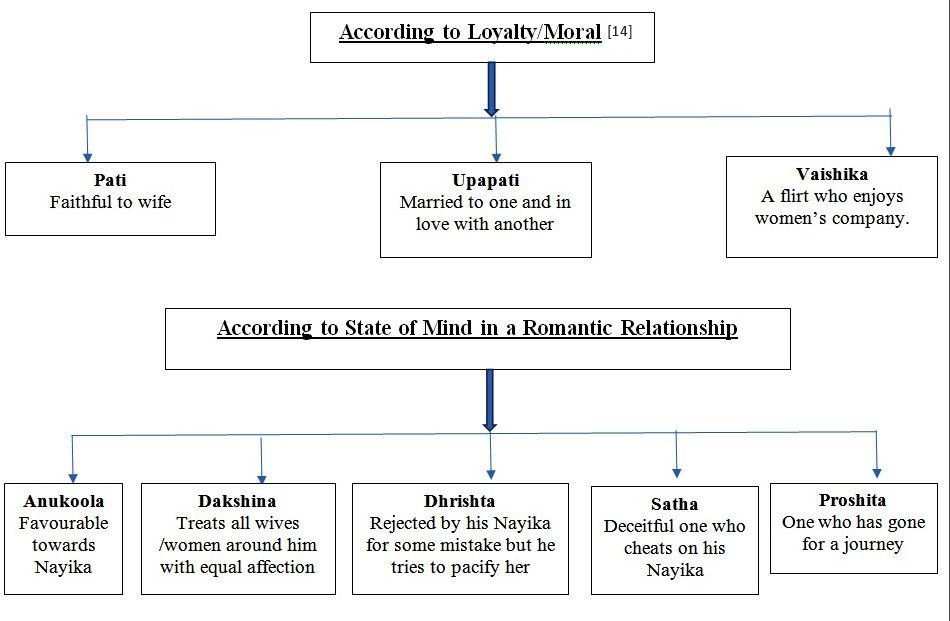

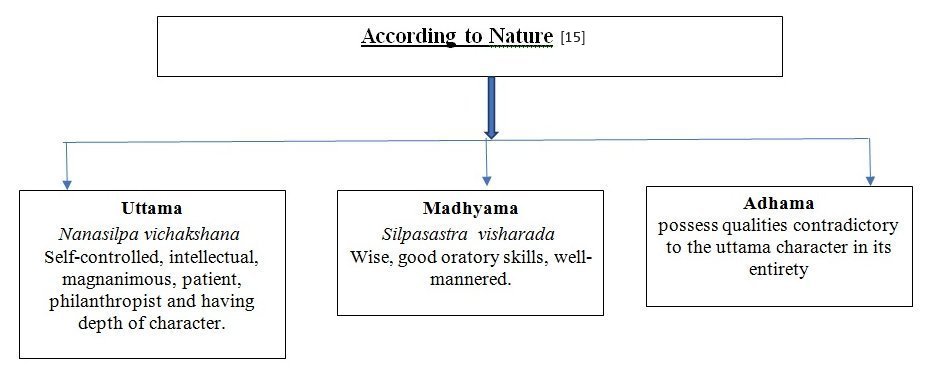

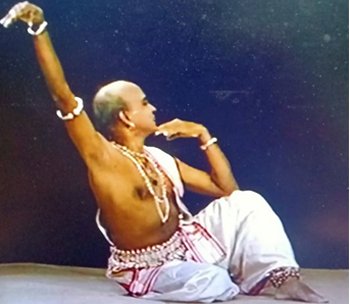

Gender study through Nayika Bheda as applied in Indian dance tradition - Srabani Basu e-mail: odissi.srabani@gmail.com April 14, 2022 (Srabani Basu started writing this article as part of the 'Indian Classical Dance Pedagogy' certification program that she has done from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte in 2021. She continues to develop it with further studies for research aspirations.) Introduction India is a country from south-east Asia that preserves an ancient yet rich cultural heritage of literature and performing arts going back to over two thousand years. This format of art that hail from different parts of the country consisting various styles of music as well as dance, have been refined and restructured post India's independence from British rule in the 20th century. These are recognized as Indian classical art forms and are dedicatedly practiced in the 'Guru-Shishya Parampara' or the teacher-disciple tradition. This tradition is predominantly influenced from Natya Shastra, which is an encyclopaedic treatise on the performing arts [1][2] written in Sanskrit by sage Bharata dated between 200BCE and 200CE [3][4].The text consists of 36 chapters with a cumulative total of 6000 poetic verses. The subjects covered by the treatise include dramatic composition, structure of a play and the construction of a stage to host it, genres of acting, body movements, make up and costumes, role and goals of an art director, the musical scales, musical instruments and the integration of music with art performance [5][6]. The Natya Shastra is also notable for its aesthetic 'Rasa' theory asserting entertainment as just a secondary goal of performing arts while primary goal being to transport the audience to a parallel reality experiencing own consciousness and reflecting on spiritual values [7][8]. The grammar or technicalities of Indian classical dance is primarily derived from Natya Shastra, while its choreographic elaborations on abhinaya or expressional aspects are largely influenced by episodes from mythological epics such as 'The Ramayana', 'The Mahabharata', literary creations by poets Kalidasa, Jayadeva as well as numerous regional folklores. A nuanced and vast discussion on gender can be found first in the Natya Shastra and further elaborated in several Sanskrit works on dramaturgy and poetics later till 15th-18th century[9], in which the female protagonist or the heroine is termed as 'Nayika' and the male protagonist or the hero is termed as 'Nayaka'. Various classifications of these heroes and heroines based on their characteristic attributes, physical appearance, social status, state of mind or behaviour in a romantic relationship etc - are described in detail here which is studied as 'Nayaka-Nayika bheda'. Many of these definitions or categories can be mapped with the characters as depicted in prior mentioned texts which were written in India before, during or even at a much later time frame of Natya Shastra. Such classifications are partially applied in Indian classical dance within the scope of the content it refers from these ancient works of literature specified earlier. In this article, I elaborate some of the Nayikas who are majorly relevant in India's dance tradition and their Nayaka counterparts to establish certain clarity on the gender nuances as perceived in pre-Islamic and pre-colonized Indian society. In this process, I also take the reference of conspicuous female protagonists of diverse and distinctive traits specifically from the Vedic period epics 'The Ramayana' (by sage Valmiki, approximately dated between 7th century BCE-3rd century CE),'The Mahabharata' (by sage Vyasa, approximately dated between 3rd century BCE-3rd century CE) and the medieval period poem 'Gita Govinda' (by poet Jayadeva, dated to 12th century). However, since any historic evidence of art or literature essentially reflects the social structure of that particular era and we are looking at this topic through the lens of 21st century influenced with sociological concepts such as feminism-women empowerment-gender equity, I try to seek answers to the pertinent questions: How do some of the present day Indian classical dance practitioners and scholars look at gender emancipation and its relevance with 'Nayika Bheda' illustrated in Natya Shastra and other related texts? How are some of the eminent female characters from Indian mythology perceived today? How does the uninhibited display of feminine sexual agency in these text references appear in contemporary times? How does the Indian classical dance pieces choreographed in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries specifically portray Gita Govinda's nayika Radha through the various shades of heroines?Apart from textual research, I interviewed eminent Indian classical dancers and dance scholars Dr. Rohini Dandavate, Dr. Arshiya Sethi, Dr. Kaustavi Sarkar, Dr. Janaki Rangarajan, Momm Ganguly, Uma Dogra, Rukmini Vijayakumar, Bani Ray, Subikash Mukherjee and Rahul Acharya to understand their viewpoints in this regard which are explained in later sections. Before getting started with the classification and definition of those 2nd century nayikas from Natya Shastra whose portrayals hold significant importance in present time Indian classical dance choreographies, it is imperative to touch base on the basic gender equity concept [10] of 21st century to continue further analysis on contemporary applicability of gender emancipation as found in the Indian tradition of literary and performing arts. While there are varied perspectives on feminism, prominent philosopher Simone de Beauvoir's remark 'One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman' presses upon the fact that men and women are born equal with only a different anatomy but society creates gender stereotypes imposing notions of masculinity or femininity plotted with restrictions. Although the individual interpretation may differ, feminism is fundamentally a vast range of socio-political movements, and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. It is a universal concept advocating equality of opportunity irrespective of gender and a liberating idea of equity across social-racial-religious divisions. With this brief overview of feminism, I shall further elaborate the nayikas from Natya Shastra who are majorly celebrated in Indian classical dance styles. Natyashastric Nayikas in the scope of Indian classical dance The primary classification of these Nayikas deals with their age, morals and nature but only in the context of a romantic relationship with Nayaka or 'hero'. The brief elaboration of the categories is as below [11]-   There is another category of Nayikas though, purely based on psycho-physical appearance. [12] These are Padmini, Chitrini, Shankhini, Hastini which is not directly related to love but neither does it mention any significant attributes of women in terms of knowledge or skills. For example - The Padmini woman has been described to be beautiful in appearance, her body having sweet odour and her complexion as the hue of gold. She is bashful, wise, generous and tender hearted. She is cheerful, her body and clothes are always clean, she eats and sleeps little. Her private parts are hairless. She has less of arrogance, anger and desire for lovemaking than other women. Further comes the concept of 'Ashta Nayikas' which is widely demonstrated in Indian classical dance through numerous choreographies on ancient classical texts such as Gita Govinda by poet Jayadeva, stories or situations from 'The Ramayana', 'The Mahabharata', compositions by poet Kalidasa, regional poems etc. Ashta Nayika literally means eight nayikas based on diverse mental states or 'avastha' in the course of their relationship with Nayaka [13].  While a brief elaboration has been given on the major classification of romantic Nayikas, the corresponding Nayakas need to be deliberated as well in order to understand the gender nuances in a better way. Natyashastric Nayakas equivalent to the specified Nayikas According to Loyalty, State of Mind and Nature, the basic classification approach of Nayakas apparently looks similar to the Nayika Bheda described in above section.   Dr. Parimal Phadke, a senior Bharatanatyam exponent and scholar, mentions in his article on Nayaka Bheda [15 ] - "It is interesting to note that Bharata gives vichakshana for Uttama characters and visharada for madhyama characters. So, the uttama characters are supposed to be skilled to the extent that they have knowledge about it and the Madhyama characters are supposed to be proficient enough to make a professional use of it.... Similar is the classification of the female characters. A significant point which I observed was that nowhere in the list of qualities of the superior female character, we find presence of intellect, skilful, proficient in arts etc." Adding to the same context, there are four more types of Nayaka derived from Uttama and Madhyama variety, a similar reference of which is noticeably absent in the Nayika's taxonomies discussed so far. These are: • Dhiroddhata - Brave and Haughty • Dhiralalita - Brave and Sportive • Dhirodatta - Brave and Magnanimous • Dhiraprashanta - Brave and Calm This categorization establishes the fact to a considerable extent that traditional choreographic content of Indian classical dance not only deal with the Nayaka's condition in love but it also derives his independent qualities, unlike the Nayikas who are commonly portrayed through the angle of romantic relationships. In this line of thought, myself as an Indian classical dancer and dance enthusiast would like to mention few of my observations on the most popular abhinaya choreographies in India's dance tradition that majorly revolve around nayika Draupadi during her infamous disrobing episode in the Mahabharata where her friend Krishna being the nayaka saving her honour, nayika Radha pining for her love of Krishna and yearning for union with him, nayika Sita getting abducted by Rakshasa king Ravana and her husband Lord Rama rescuing her by killing Ravana in war etc, in which all these heroines are portrayed in distress and the heroes play the role of their saviours. While various literary research on these and many other nayikas delineate them as strong personas with distinct knowledge-confidence-willpower-courage and decision making qualities that I would bring up in later sections, it is not observed much in the common choreographic content that usually celebrate valorous and generous nayakas. Although there are dance pieces choreographed in praise of Goddesses of power-wisdom-beauty-wealth same way as the Gods are glorified, a Goddess can't be typically categorized as a nayika. Continuing further on some of the questions specified in the introduction, I hereby elaborate not only the present day relevance of natyashastric nayikas but also interpretation of social status of women in ancient India through this subject along with other textual references as applicable. Interpretation of women's social status from 'Nayaka-Nayika Bheda' - Then vs Now! Knowing till this point, perhaps few questions may arise in the contemporary readers' mind that is influenced with the gender equity concept. Such as, considering the well agreed fact that art reflects society, does the 'Nayaka-Nayika Bheda' imply an oppressed social status of women in the time frame of Natya Shastra? Why a woman would be measured as 'Uttama' or 'Superior' for generously tolerating her lover/husband's wrong doings? Is it an attribute to be encouraged to live a respectable life? Or why the Nayakas aren't only classified based on romantic relationship like the Nayikas but their characteristic attributes are accredited as well? Even though all these questions sound admissible, it is important to note here that only a section of 'Nayaka-Nayika Bheda' which is significantly and commonly applied in content selection for the Indian classical dance choreographies, has been chosen in this paper for a detailed elaboration. Hence it would be an incomplete approach of questioning women's social status as a whole in the history of India itself without addressing various other definitions of Nayikas or women in general, few of which I touch upon further in later sections. However, since Natya Shastra is essentially an ancient text on nuances of 'performing arts', an attempt is necessary to identify the similarities of Nayika/Nayaka attributes mentioned so far with the depiction of gender stereotypes in the commercialized art forms of contemporary time frame post the formal origination of liberal feminism. Objectification of women universally in various modern mediums of popular art such as music videos as well as 'item dance' in Bollywood movies, portrayal of heroines as eye-candies with 'perfect physical beauty desirable to men' just as the love interest of the heroine popular movie-literature-theatre doesn't quite demonstrate the supposedly raised extensive social awareness on women empowerment. Rather this aspect conceptually has a striking resemblance with the Nayikas classified based on physical appearance in Natya Shastra. On the contrary, while women are extensively projected as pleasurable commodities even in television advertisements promoting products or services, it is an irony that manifestation of female sexuality in modern society still remains a taboo. "Sociological research on gender suggests that children are socialized into heteronormative gender norms from a very early age: elementary age boys are allowed to objectify girls, while girls are reprimanded and corrected for any displays of sexuality (Gansen 2017)... ...Popular culture is dominated by sexually suggestive music videos, ranging from Nicki Minaj's "Anaconda" (2014) to Missy Eliot's "Work It" (2002) (Karsay et al. 2019). In these music videos, women embrace their sexuality both visually and sonically. Sexually suggestive behaviour is labelled "deviant," because historically, women have been praised for their modesty and chastity (Anderson et. al 2019)...However, men, specifically White men, are not scrutinized for equally suggestive music videos. Instead, White men are encouraged to be suggestive, under the pretence that "boys will be boys" (Turner 2011). Both attitudes depict implicit biases influenced by racialized gender stereotypes: overgeneralizations based on a coalescence of race and gender (Crenshaw 1989)."[16] Another aspect I observe on the current day applicability of specified Natyashastric Nayikas is, love themes are easier to portray because of its eternal desirability compared to the more challenging depiction of other emotions and hence it might have been revived in numerous shades as the most common topic, be it in ancient or contemporary art. Correspondingly as far as different emotional states of a romantic relationship is concerned, it can have timeless pertinence to a decent extent regardless of any era for human psyche and that way some explicit Nayikas as well as Nayakas could still hold their due significance intact.Yet, over exploration of love themes inopportunely may create a limitation factor to interpret various other aspects of gender emancipation !While explaining her viewpoint, senior Kathak exponent-scholar-activist Dr. Arshiya Sethi rather prefers to approach feminist issue separately through gender specific studies keeping it aside from dance. She feels that the primary concern in Nayika Bheda as perceived in Indian dance tradition, is that the nayika is defined not with her multiple identities but with reference to only one identity, one role, one fractal of a very rich life. It is love with reference to a nayaka and hers is often a reactive situation, so where does her agency lie? In that term, she perceives it to be inadequate. Her perspective says that we have mosaics of multiple identities such as political-economic-religious-spiritual-social lives etc which don't get reflected in this format of Nayika Bheda and hence it is increasingly hard for her to keep accepting this text other than the fact when only the 'love' context has to play its role. According to Dr.Sethi, it is beautiful only from a particular aspect but inadequate from the wholeness of our lives in the 21st century. Referring to the earlier point I mentioned as to be further discussed on entirety of 'Nayaka-Nayika Bheda' from Natya Shastra which isn't fully covered in the context of Indian classical dance choreographic content, celebrated Odissi dancer and scholar Rahul Acharya emphasizes that women have always been treated with great deal of independence in ancient India. They played more important role in shaping the society than men, and that is the reason Bharata has given more variety on Nayikas than Nayakas. Acharya further specifies an instance that, compared to just 48 Nayakas, Natya Shastra chapter 23 'Vaishikopachara' and 24 'Stripungshopachara' talk about 384 Nayikas. This includes Dhira, Lalita, Udatta, Nibhrutta as independent nayikas as well as Bahira and Abhyantara nayikas who were connected with the king's court. Independent scholar women were Bahira nayikas who lived outside, they were considered as courtesans and were expert linguists having significant roles to play in state affairs. Abhyantara had access to the inner chambers of the king where secret discussions used to go on and they took part in it. He also reminds about the widely practiced ritual of Swayamvara - the right of a woman to choose her husband that can be considered as the biggest example of women's independence during this time. According to Acharya, oppression of women has come into play as a result of Islamic invasion and British colonization resulting in women empowerment, liberation, gender equality concepts or movements which didn't have enough relevance in ancient Indian society. Further to his view, as I contemplate the precolonial-pre Islamic society of India in the Vedic era which celebrated the rishikas or the intellectual women like Apala Atreyi-Lopamudra-Gosha Kakshivati or the proficiency of the courtesans such as Amrapali-Purasati-Barani in art, aesthetics as well as spirituality, it feels inappropriate to derive an over simplified conclusion labelling the entire subject and time of Nayika Bheda as irrelevant or regressive to the present time. [17][18] Interestingly, my thought is echoed by senior Mohiniattam exponent Momm Ganguly when she points out the fact that even though most of the religious texts from other religions are largely partial towards men, a significant matriarchal influence in Hindu texts can be found in the time of the Vedas. Concentrating on the section of 'Nayaka-Nayika Bheda' majorly relevant to Indian classical dance, senior Odissi dancer and scholar Dr. Rohini Dandavate explains that in order to derive the applicability of feminism in this context, it calls readers to develop a wide approach which encompasses 'various interpretations of the definitions'! Perspectives may vary according to an individual's upbringing, social conditioning, life experiences and outlook on the subject of feminism. The emotional nuances of nayikas and nayakas described in the Natya Shastra roots in the way of life envisioned by the author from that period in time. As a performing artist, in the present time when life experiences have evolved, it becomes necessary to understand the context and applicability of Bharata's concepts in relation to the underlying flavour of feminism and women empowerment of the present generations which discusses the women's right to 'make one's own choices'. Dr. Dandavate further clarified that the section of Nayika Bheda implemented in Indian classical dance primarily defines the various emotions of a woman as portrayed in a man and woman relationship, focusing on exploring a woman's affectionate side of nature. So as opposed to the usual concept of gender rivalry, another nuance of feminine qualityshe acknowledges here that lies in the immense strength of patience, forgiveness and maintaining poise even at the time of extreme rage, which is portrayed as the characteristics of an Uttama Nayika. An apt example of nayika Sita from 'The Ramayana' is cited by Dr. Dandavate in this context, where it is Sita's choice to accept and forgive her husband Lord Rama after enduring the public humiliation of 'Agni-Pariksha' (an ordeal of fire) at the island of Lanka, perhaps for the sake of her love and dedication for him, along with her responsibility as a queen! But at a later stage it is again Sita who, after raising her twins (Luv-Kush with Rama) as a single mother, chose to gracefully aloof herself forever when her faithfulness towards him was doubted through these children, because she wasn't ready to tolerate it anymore. Hence, she demonstrated empowerment in her way according to the situation, without deviating from her qualities as an Uttama Nayika. Similarly, a retelling of 'The Ramayana' from Sita's perspective, 'The Girl who Chose', written by celebrated Indian mythologist Dr. Devdutt Pattnaik sets forth certain choices made by Sita which presents views much alike to the ones explained by Dr. Dandavate. Despite Sita being commonly perceived as a submissive woman without her own voice, Dr. Pattnaik highlights in his book how as an Uttama Nayika she actually took control of her course of actions in various turning points of her life - be it not choosing her husband in her Swayamvara and letting her father king Janaka along with Lord Shiva's bow choose Lord Rama for her, OR accompanying Lord Rama in his 14 years of forest exile, OR crossing the safe boundary drawn by her brother-in-law Lakshmana in the forest for offering alms to the disguised Rakshasa king Ravana that led to her abduction, OR not accepting the mighty Hanumana's proposal to easily and safely carry her out of Ravana's kingdom Lanka prioritising Lord Rama's reputation as a prince to cross the sea and rescue his wife by killing Ravana, OR both the 'Agni Pariksha' situations mentioned in above section.[19] Parallel to seeking relevance of Nayika Bheda in modern time, as this article also tries to capture the limitations of Natyashastric nuances of Nayikas within scope of Indian classical dance that prevent to derive a holistic view on ancient India's social status of women and their sexual agency, few more distinguished female characters need to be mentioned from the rich Indian mythological and religious heritage. More mythological and religious references of feminine agency One such data point of the famous 'Panch Kanya' verse fits appropriate in which Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, Tara and Mandodari - these five Nayikas from the epics are venerated as ideal women and chaste wives in one view, despite their association with more than one man. It sounds to be an apparent paradox considering how female sexuality is practically stigmatized or misjudged in the present society. [20] Ahalyā draupadī kuntī tārā mandodarī tathā। pańcakanyāḥ smarennityaṃ mahāpātakanāśinīm॥ It means: 'Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, Tara and Mandodari Invoking daily the virgins five / Destroys the greatest failings' Among these five women, Ahalya-Tara-Mandodari are from 'The Ramayana' and Draupadi-Kunti are from 'The Mahabharata'. Although many layers are to be involved in detailed study of their character portrayal, I am going by a very brief background to introduce their relevance for this paper considering the limited opportunity that we have here to dive any deeper. Ahalya was cursed by her husband Sage Gautama for her infidelity with Indra (the king of the gods). Tara and Mandodari both were queens of the Vanara and the Rakshasa clans respectively and both were married to the brothers (Sugriva and Vibhishana) of their kings (Vali and Ravana) upon the kings' death. Kunti was married to King Pandu of the Kuru clan but she was empowered with a boon to summon any god of her choice to bear his son. She gave birth to Karna (prior to her marriage), Yudhishthira, Bheema and Arjuna from the gods Surya (the Sun god), Dharma (the god of justice), Vayu (the god of wind) and Indra (the king of all the gods in heaven) respectively. Her sons are the primary protagonists of the Mahabharata. Kunti's sons Yudhishthira-Bheema-Arjuna along with their step-brothers Nakula and Sahadeva from Madri, another queen of King Pandu- are known as the Pandavas, Draupadi being their common wife. Draupadi is the pivotal heroine of the epic who is said to be the one with a divine birth from fire, signifying her extraordinarily knowledgeable and fierce persona. Pradip Bhattacharya opens his book 'Pancha Kanya: The Five Virgins of Indian Epics. A Quest in Search of Meaning' with an assertion that this ancient exhortation is relevant in today's global world. The first chapter, 'Pancha Kanya: A Quest in Meaning,' travels through internet research, e-mailed reader responses, performances, and even corporation reports such as the Panchakanya Group in Nepal. It teases the concept of 'kanya' versus 'sati,' explores all of the variations to the exhortation, and concludes with the necessity of delving into the subject 'in the context of the powerful wave of feminism sweeping in from the West' ...It is this feminist 'eye' that sets Bhattacharya's analysis apart from most academic scholarship. Ahalya is not an innocent victim, as her later incarnations in various texts purport her to be. Bhattacharya delves into the Uttarakanda, Mahabharata version, Brahma Purana, Shiva Purana, and Kathasaritsagar. He even explores Pratibha Ray's novel Mahamoha (1997) and Anita Ratnam's dance composition, as well as the television Ahalya, for modern relevance....The analysis of the characters of Tara and Mandodari as strategists, politicians, visionaries, and no simple helpmates to their male consorts is brilliant and convincing... He methodically proves that Kunti was a strategist who made the alliances for her sons, who machinated Draupadi's marriage with all five, who ruthlessly had the Nisadha woman and her sons killed, and who disabled Karna. With a typical Bhattacharya twist he also plants a seed in the readers' minds that Dharma could be Vidura and that Kunti may have had four men rather than four gods as her partners; the work continues to be 'a quest in meaning' and fodder for the feminist...In Draupadi, Bhattacharya finds a woman who is not inferior to her mother-in-law in her machinations. Draupadi is also no Sita, she is a kanya, not a pativrata, a sexually independent woman, 'the goddess of the common people' (103; citing Prema Nandakumar). Through quotes from Mallika Sarabhai (Draupadi in Peter Brooks' Mahabharata) and literary citations, Bhattacharya concludes 'Draupadi's character speaks powerfully to oppressed womanhood today' (105)... The analysis again centres around the duo as powerful females, as creators of their own destinies, independent of any male partners...Bhattacharya summarizes the qualities of a kanya, as he unpeels layer after layer and draws parallels between these five women. The most significant question is reiterated, a woman's sexuality vis-a-vis her morality, necessitating the issue of a paradigm shift, 'sanitizing' the kanyas into satis in later patriarchal literature (113). [21] Rahul Acharya mentions that Valmiki Ramayana and Vyasa Mahabharata are considered as Itihasa or recorded history reflecting the society of their time. He too cites certain examples of prominent women from these epics such as Shakuntala, Subhadra along with Ahalya and Draupadi. Acharya explains the situations of Ahalya living in isolation in the wilderness of the forest due to the curse of her husband sage Gautama, Draupadi having enough confidence to confront and question the perplexed grandsire Bheeshma on how it was lawfully possible for Yudhishthira to pawn her in the game of dice while he himself already became slave, Subhadra choosing not to marry the primary antagonist of 'the Mahabharata' Duryodhana who was selected by her elder brother Balarama and instead deciding to elope and marry Arjuna being proactive in riding his chariot, Shakuntala agreeing to marry King Dushyanta only under one condition that her son would become the king - none of which could have been possible had these nayikas not been independent women both by their thoughts and actions. In addition to the above discussed references, Hinduism as the oldest religion of ancient India still practices worship of Goddesses reflecting shades of valour (Durga-Kali), knowledge (Saraswati), wealth (Lakshmi). Even though Goddesses can't be typically termed as Nayikas, but such celebration of the supreme feminine power don't quite diverge from the base idea of women empowerment.[22] Hence, the detailed nuances of 'Nayaka-Nayika Bheda' even outside the scope of Indian classical dance along with related literary references of that specific time frame is essential to be considered in order to develop an understanding on women's social status of that era before deriving a conclusion on the same as illiberal or oppressed. So to address the introductory question on women empowerment or gender emancipation as derived from the representation of women according to Nayika Bheda within the scope of Indian dance tradition, analysing a specific example of a nayika who is extensively celebrated in its choreographic content is essential to understand this topic further. Hence, I choose the textual reference of Gita Govinda written by poet Jayadeva back in the 12th century, for highlighting shades of Nayika Radha who has deeply influenced numerous compositions in most of the Indian classical dance styles. As celebrated Mohiniattam artiste Momm Ganguly expresses her thoughts on this epic love poem, she mentions that even though it was composed during the Vaishnava cult movement when the society has gone through different phases since the Vedic period and the patriarchal order has already got established pushing women towards a secondary position in the society, Gita Govinda demonstrates a liberating approach defying that social norm. In the following section, I intend to delineate the nuances of an empowered woman portrayed in Radha from Gita Govinda. Gita Govinda's Radha in various shades of the Nayikas Gita Govinda is a dramatization of the love sport between Lord Krishna-the cowherd and Radha-the milkmaid. It is essentially a metaphor for the cosmic drama that unfolds in both human and divine level which move concurrently throughout this epic romantic poem with great beauty and complexity. I delve into some of the verses from Gita Govinda to understand the feminine agency aspect in portrayal of the Nayika or the female protagonist Radha. To begin with an example, in the sixth Ashtapadi (eight-versed couplet) 'Sakhi He' of this magnum opus, Radha expresses her burning desire to reunite with the male protagonist Krishna in an unhesitant manner to her confidante. She reminisces a blissful evening spent with her beloved and says: 'Alasa Nimeelita Lochanaya Pulakavali Lalita Kapolam'/ 'Charana ranita mani nupuraya paripurita surata vitaanam - mukhara vishrunkhala mekhalaya sakachagraha chumbana daanam'! which means 'My eyes close languidly as I feel the flesh quiver on his cheek'/ 'jewel anklets ring at my feet as he reaches the height of passion, my belt falls noisily; he draws back my hair to kiss me'[23]! It is also significant to note that Radha has been portrayed as an Abhisarika Nayika in this specific poem where, she is the one who sets aside her modesty and secretly steps out to meet her Nayaka. As far as an alternate perspective is concerned, thus Radha too emerges as a strong-willed woman through her unwavering expression of agency, though in a dissimilar fashion from what we observe in Sita. As stated by writer Namita Gokhale [24]: "Radha is an all-too-human goddess, a sublime yet sensual emblem of mortal and divine love. She is subversive in that she possesses an autonomy rarely available to feminine deities. She lives by her own rules, and not those of the world. She is the essential Rasika, the aesthete of passion, and her wild heart belongs only to herself... ...Radha, the bucolic milkmaid, follows the dictates of her heart, of her instincts, of her passion, to seek union with her innermost self. She is her own mistress even in the act of surrender to her beloved. And it is this aspect of her that is worshipped, if not emulated, in shrines, temples and festivals all across India even today." In the above context of Radha following the dictate of her wild heart filled with passion and surrender for Krishna, a verse from the fifth Ashtapadi 'Raase Harim iha' expresses her feelings as a Virahotkanthita Nayika where she apparently is depicted as a woman pining to unite with her lover who doesn't acknowledge her eminence. Here she becomes indignant after seeing Krishna enjoying affectionate exchanges with all the Gopis in the groves of Vrindavan. She immediately departs for another part of the forest, feels wretched but still tells her friend- 'sańcarad-adhara-sudha-madhura-dhvani-mukharita-mohana-vamsham | chalita-dg-ańcala-chańcala-mauli-kapola-vilola-vatasam | rase harimihavihita-vilasam smarati mano mama kruta-parihasam'. It means 'How astonishing it is that in this räsa festival, Madhuripu (Krishna) has abandoned Me and He is roguishly amusing Himself with other alluring girls. Despite this, again and again I remember Him in My heart. He fills the flute resting in His lotus hands with the nectar of His lips, nectar that streams forth as a sweet suggestive melody. When He glances flirtatiously from the corners of His eyes, His jewelled headdress quivers as His earrings swing against His cheeks.Over and over I remember Hari's attractive dark complexion, His laughter and His amusing behaviour.'[23] In this line of feminine agency with a different insight from a human level, Dr. Dandavate's opinion on a common woman's choice of forgiveness to a certain extent for the relationship/family/children's wellbeing barring the unscrupulous scenarios, is all about acknowledging her strength that strives for construction over choosing destruction. However, she also clarifies that from a different perception this can be termed as compromise which again establishes the fact that such judgements depend on how an empowered woman is interpreted by an individual. In stark contrast to the earlier verse, it is again Radha who condemns Krishna in her jealous anger in the seventeenth Ashtapadi 'Yahi Madhava' suspecting his infidelity. As a Khandita and Vipralabdha nayika she denounces him bitterly as he bows before her, pleading forgiveness. The verse says- 'Yahi madhava yahi kesava, ma vada kaitava vadam | tam anusarasarasiruha-lochana, yathava harati vishadam' which means 'Go away O Madhava, leave me O Keshava, don't plead your lies with me | Go after that lotus-eyed woman, she will ease your despair'.[23] While discussing on Gita Govinda in the context of Nayika Bheda, Dr. Sethi too acknowledges it to be quite progressive for its time as it talks about certain nuances that even 21st century India doesn't see that much as yet - it is an equal surrender by the male protagonist Lord Krishna. She specified two very high points - the first one to be the nineteenth Ashtapadi 'Priye Charusheele' with the iconic verse of - 'Smara garala khandanam mama shirasi mandanam, Dehi pada pallava mudaram' where Krishna doesn't hesitate and asks the Khandita and Vipralabdha Nayika Radha- 'place your foot on my head-a sublime flower destroying poison of love'[23] to show his devotion for her as well as to apologise for causing her pain. And the second point being the twenty fourth i.e. the final Ashtapadi 'Kuru Yadu Nandana' depicting Swadhinbhartrika Nayika Radha's loving command over Krishna asking him to reapply kohl in her eye, redo her hair and rearrange her ornaments which are in disarray after their long-awaited passionate reunion, and Krishna lovingly decorates her in return. Dr. Sethi looks at it as a metaphorical representation of Radha asking Krishna to give her back her 'Radhitwa' or her true self by beautifully voicing her agency. Here Radha says- 'kuru yadu-nandana candana-shishira, tarena karena payodhare | mruga-mada-patrakamatra mano-bhava, mangala-kalasha-sahodare / ali-kula-bhańjana mańjanakam, rati-nayaka-sayaka-mochane | tvad-adhara-chumbana-lambita-kajjalam, ujjvalaya priyalocane / mama ruchire chikure kuru mananda, manasija-dhvaja-chamare | rati-galite lalite kusumani, shikhandi-shikhandaka-damare / sarasa-ghane jaghane mama sambara, darana-varana-kandare | mani-rashana-vasanabharanani subha shaya vasaya sundare' which means 'O joy of the Yadu clan, your hand is cooler than the sandal balm on my breast, paint a leaf design with deer musk here on love's ritual vessel / my love, draw kohl glossier than a swarm of black bees on my eyes, your lips kissed away the lampblack bow that shoots arrows of the love god Madana (cupid) / O respectful one, fix flowers in my hair loosened by loveplay, make a fly whisk outshining peacock plumage to be the banner of love / my beautiful loins are a deep cavern to take the thrusts of love - cover them with jewelled girdles, cloths and ornaments - O Krishna!'[23] Hence, despite Gita Govinda revolving around the predominant theme that Nayika Radha yearns to unite with her Nayaka Krishna, her untethered expressions of love-desire-distress-rage-endearing command over her beloved and also her forgiveness, prioritizing her feelings for him establishes her agency of an empowered Nayika which can't be outright disregarded as irrelevant at all to the present time. As quoted from Debotri Dhar... "Radha's position as Krishna's lover is clearly in defiance of society's norms, a fact that becomes all the more apparent when one considers the sexually explicit nature of tracts such as those in the Gita-Govinda that describe in erotic detail the powerful manifestation of Radha's sexual desire in the arms of Krishna the God-incarnate. In comparison to other key Hindu goddesses such as Sita, whose devotion to their men is very much in keeping with societal mores, Radha therefore seems to stand out as an anomaly, an improbable "feminist" icon within mainstream mythology who challenges the very bedrock of patriarchy through her provocative agency." [25] Analysis: In view of all the above aspects - 1. There have been considerable references from ancient India through Vedic-mythological-religious texts which distinguish women's power, knowledge, choices and proficiency in arts. Hence, it would be prejudicial to derive women's social status as oppressed based on a narrowed down approach on the romantic nayikas of Natya Shastra that are principally applied in Indian classical dance. 2. At the same time, continued prevalent demonstration of love themes-gender stereotypes-commodification of women despite social stigma over their sexuality in contemporary popular art forms - also rules out the categorization of Nayika Bheda, as entirely irrelevant from modern day portrayal of ideal womanhood and the usual struggles women still face to break the shackle. 3. Perspectives are equally important to decipher the qualities or agency of nayikas as different individuals be it scholars or commoners nurture different outlooks in this subject, analysis of Uttama Nayika in Sita being a predominant example. 4. Significantly, Gita Govinda's Radha depicting characteristics of various such Nayikas, also demonstrates a married woman's free will to choose her passion for another man, despite the fact that it was composed much later than the Natya Shastra when the society had already become conservative for women. Finer nuances of 'Nayaka-Nayika Bheda' is required to be interpreted in context of the applicable time frame to comprehend the underlying flavour of empowered women who were celebrated as lovers and nurturers! I shall further try a brief analysis of the choreographic portrayal of Radha in Gita Govinda through Indian classical dance. Having this textual understanding developed, it is important to converse on how did the Indian classical dance choreographies formed in late 20th or early 21st century deal with such verses while portraying the various shades of Nayikas in Gita Govinda's Radha? However, it is essential to note that choreographic interpretation of Gita Govinda couplets are built more on the foundation of the divine romance and spiritual aspect of this text, than the human or social aspect dealing with feminine agency which I elaborated in the earlier sections. Portrayal of Gita Govinda's Radha in Indian classical dance choreographies As a practitioner of Odissi in Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra gharana (style/school) for nearly two decades, I have always been an admirer of the graceful and lyrical movements of this dance form. Technically it requires adequate physical strength to portray the fluid postures which is the most coveted essence of Odissi. Hence, practicing this dance form as a way of life has inculcated a philosophy of 'strength in softness and grace' in my subconscious which plays a pivotal role when I perform or watch an Ashtapadi depicting Radha as Virahotkanthita (distressed by separation from her beloved), Abhisarika (secretly going to meet her beloved), Khandita (enraged with her beloved) or Swadhinbhartrika (having her beloved in subjection) nayika. As applicable to the fundamental style of Mohapatra's choreography, I find Radha's portrayal elegant and poised irrespective of the 'bhava' or emotion she expresses as the Uttama Nayika.  Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra depicting an authorized Radha as the Swadhinbhartrika Nayika It also depends on the persona of the artist and their individual mode of character interpretation when they perform a piece. As identified by Odissi dancer and scholar Dr. Kaustavi Sarkar during a conversation over this subject, a contrast of a stronger demeanour of Radha by Surupa Sen compared to a softer representation by Sujata Mohapatra can be considered as an example in this context, both being celebrated senior Odissi exponents.  Sujata Mohapatra depicting a coy Radha as the Abhisarika Nayika where she secretly steps out of her home on a long, silent night longing to meet Krishna During my interview, while I asked Dr. Rohini Dandavate's sights on Ashtapadi choreographies in light of feminism as a senior disciple of Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra, she elucidated the fact that art reflects life and vice-versa. So, if we look at Mohapatra's interpretation of Radha as a devoted Nayika, she touches Krishna's feet in most of his choreographies. This is according to Mohapatra's own life experience of his time when touching husband's feet by a wife used to be a common ritualistic phenomenon in an Oriya (or perhaps in any Indian) household. On the other hand, as depicted in the choreographies of her Guru Debaprasad Das (another Adi Guru of Odissi) senior exponent Bani Ray observes Radha as more powerful, superior, rebellious, strong-willed woman who does not hesitate to incur wrath of her family and village to be with Krishna who himself surrenders to the kind of love Radha offers. Ray points out Radha's stance and her straight glance at Krishna's eyes as choreographed by her Guru, projecting her self-assurance and self-respect, the attitude of a confident woman who sees Krishna as her equal and her decision to be with him shows that she is not defined by her community's opinions. According to my own observation of Bharatanatyam as a dance form unswervingly portraying the technicality of physical strength through its stances-movements-gestures, it enables to depict Khandita Nayika with stronger and more powerful emotions.  Bharatanatyam exponent Rukmini Vijayakumar depicting an enraged and hurt Radha as the Khandita I intend to get a varied perception on this matter from practitioners of other Indian classical dance styles, through seeking inputs from Bharatanatyam exponent Rukmini Vijayakumar and Mohiniattam exponent Momm Ganguly. From a spiritual viewpoint, Vijayakumar exemplifies that while enacting Khandita Nayika, she recognizes Radha as a representation of all humanity who has a limited perception of oneself, not knowing that Krishna is within. The emotions that she traverses of jealousy and anger-resentment-love and possession are the feelings everyone experiences as human beings, when we associate with our bodies and our identities. Ganguly clarified that Mohiniattam's first stance itself sets huge expectation from a woman as dutiful, matured, elegant and the one who exhibits no power or arrogance. It is a dance of the enchantress holding softness and devotion (bhakti) as the 'sthayi bhava' which technically needs extreme endurance and stamina, but abhinaya in Mohiniattam is never strong as it is against the aesthetics of a Mohini. So that boundary of an enchantress/mohini comes in the way even when depicting strong negative emotions of Radha as Khandita Nayika. While in Kathak form of dance, it is quite rare to find Gita Govinda's Ashtapadi performances, I reached out to celebrated senior Kathak exponent Uma Dogra who has choreographed and performed three of the renowned poems - 'Sakhi he', 'Yahi Madhava' and 'Dhira sameere'. Dogra feels that the challenge in Kathak is abhinaya or the expressional aspect, which is way different from other Indian classical dance forms. The abhinaya here is very sahaj or natural, with lesser usage of stubborn hastas (hand gestures) portraying the specific meaning of words, but such hastas are necessary to portray the Ashtapadis. The depiction of Krishna is also not similar to what it is in the eastern or southern Indian classical dance forms. She specifies that choreography of 'Sakhi he' was challenging to depict the bold and beautiful Radha as Abhisarika Nayika who is vocal about her desires for Krishna to her confidante/Sakhi whom Dogra considers to be her Guru (spiritual guide) and not just any ordinary human being. She believes that one (Radha) can't surrender to someone (Krishna) this way unless the love is entirely devoted. So when Radha tells her Sakhi about her romantic encounter with Krishna, she actually converses with herself on how engrossed she is in love with him. Considering these aspects, she tried to present it in a different manner in her Kathak choreography. About the final Ashtapadi 'Kuru yadu nandana' that depicts Radha as Swadhinabhartrika Nayika containing erotic verses through which she voices her desire to be redecorated by Krishna after their long-awaited and passionate union, Bharatanatyam exponent and scholar Dr. Janaki Rangarajan expresses her thoughts on necessity to read between the lines of this poem. She considers it to be the most beautiful one laden with nuances that cannot be understood as is. Senior Odissi exponent and dance scholar Rahul Acharya rather wishes to address choreographic aspect separately with more detail, but he generally feels that dancers need to read a lot more to understand the context better and to digest the character. According to him, there are lot of lacuna in the research that has gone in, it should have been better had the dancers gone through the texts in more detail. He gave an example of his own choreographic work on the Ashtapadi 'Priye Charusheele' that took four months of time to compose this thirteen minute dance piece because of the extensive research he chose to do on the literary aspect. During analysis of Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra's choreography of this same dance piece, another Odissi exponent Subikash Mukherjee observes the genius of Mohapatra through elaboration of sanchari bhava that beautifully portrays Krishna's emotion for Radha when various metaphors are shown in the verse 'Tvamasi mama jeevanam, Tvamasai mama bhushanam' (You are my life, you are my ornament), such as - if you are a tree, I am the creeper which grows around you / if you are a flower, I am the bee that always finds its way to you / if you are water, I am the fish that can't live without you. He emphasizes on these expressions which show Mohapatra's excellence in understanding, processing and depicting the character of Krishna with its uniqueness along with establishing appropriate relevance of the metaphors with the main theme. From gender equality viewpoint, he finds this Ashtapadi extremely crucial as it is all about ultimate submission of Krishna to Radha representing the necessary balance in any relationship at a human level where equality and mutual respect is important. I created a website onestopgitagovinda.com as part of my research on the influence of Gita Govinda in Indian classical dance showcasing performances from various styles and interpretations of choreographies as shared by some of the artistes, along with a holistic overview of this epic poem. Conclusion: Nayika Bheda in Natya Shastra and related texts on dramaturgy-poetics as applied in Indian classical dance explores a limited scope of women's affectionate side of nature for a man-woman relationship situation which needs to be interpreted according to an individual's perception on gender emancipation. Also it is necessary to take into account the entire 'Nayaka-Nayika Bheda' and other social or textual references from that era, rather developing a straightforward notion of disapproval labelling it to be unconnected to the present time. In addition to that, a Nayika's free will and passion through Radha as described in the classical text of Gita Govinda, the feisty celebration of her various emotions together with her sexual agency mentioned through specific instances of verses, can't be outright disregarded in the context of women empowerment. Sex-positive feminism movement is a very apt analogy here, which began in the early 1980s centring on the idea that sexual freedom is an essential component of women's freedom and an avenue of pleasure for them.[26] Conversely, Indian classical dance repertoires developed during late 20th century might require inclusion of different representations of feminism through new topics, gestures or even by reinventing these classical texts as necessary by present day choreographers. Although the gender neutral technical moves and depiction of cross-dressing stories from epics-ancient folklores in Indian classical dance portraying effeminate men or manlike women breaks gender stereotypes and are fairly relevant to the contemporary gender equality and acknowledgement of individual sexual orientation notion, perhaps it is also time to try rediscovering movements for representing love as more of a companionship than the man being superior to the woman. This is how a perception towards feminism through romantic relationship or other various life aspects can be reflected in a choreographic work as far as evolvement of Indian classical dance as an art form is concerned. The metaphorical representation of various Nayikas from Bharata's Natya Shastra in Gita Govinda's Radha and other mythological female protagonists discussed in this paper, is an amalgamation of various aspects of feminine agency, and it necessitates a balanced approach to decipher the true spirit of women empowerment through the grey areas of these ancient texts filtering out the obvious inappropriations, instead of deducing a simplified supposition.  Srabani Basu is an Odissi dancer trained in Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra gharana. As an Odissi teacher, she is imparting training to students across geographies. Srabani is certified in 'Indian Classical Dance Pedagogy' from University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and as part of this program, she has created a digital project on choreographic interpretations in various Indian classical dance forms of the 12th century epic poem 'Gita Govinda' by Jayadeva. She is presently continuing her research on 'Nayika Bheda' (classification of heroines) from the 'Natya Shastra' by Bharat Muni, its literary as well as choreographic interpretations through prominent female characters from Indian mythological texts and the gender nuances in it as perceived by some of the contemporary artists-scholars. References: [1]Katherine Young; Arvind Sharma (2004). Her Voice, Her Faith: Women Speak on World Religions. Westview Press. pp. 20-21. [2]Guy L. Beck (2012). Sonic Liturgy: Ritual and Music in Hindu Tradition. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 138-139. [3]Natalia Lidova (2014). "Natyashastra". Oxford University Press. [4]Tarla Mehta (1995). Sanskrit Play Production in Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. [5]Sreenath Nair (2015). The Natyasastra and the Body in Performance: Essays on Indian Theories of Dance and Drama. McFarland. [6]Emmie Te Nijenhuis (1974). Indian Music: History and Structure. BRILL Academic. [7]Susan L. Schwartz (2004). Rasa: Performing the Divine in India. Columbia University Press. pp. 12-15. [8]Daniel Meyer-Dinkgräfe (2005). Approaches to Acting: Past and Present. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 102-104, 155-156. [9]GuptaRakesh (2013).Studies in Nayaka-Nayika Bheda [10]Laura Brunell and Elinor Burkett (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2019): "Feminism, the belief in social, economic, and political equality of the sexes. Lengermann, Patricia; Niebrugge, Gillian (2010). "Feminism". In Ritzer, G.; Ryan, J.M. (eds.). The Concise Encyclopedia of Sociology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 223. Mendus, Susan (2005) [1995]. "Feminism". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 291-294. Hawkesworth, Mary E. (2006). Globalization and Feminist Activism. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 25-27. Beasley, Chris (1999). What is Feminism?. New York: Sage. pp. 3-11. Lucknow Literature Festival.2017. Indian Feminism-https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WD0k34sjPfUKotwal Lele Medha.2019.TEDxTheOrchidSchool. "What the hell is Feminism? Is it girls against boys?"-https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bj8YPoN4OB0 [11]Biswas Sharmila (2008)."Knowing Odissi". Page:136-138 / Patki Shruti (2016) edition of Narthaki. "Nayika, the modern woman" [12]Bahadur. K P.(1972).'Rasikapriya of Keshavadasa'. Page: Ixx [13] "Erotic Literature (Sanskrit)". The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature. Vol. 2. Sahitya Akademi. 2005. Luiz Martinez, José (2001). Semiosis in Hindustani music. Motilal Banarsidas Publishers. pp. 288-95. [14] Biswas Sharmila (2008). "Knowing Odissi". Page:139-140 [15]The Nayaka Bheda according to Nature and Qualities have been referred from -Phadke Parimal. 2004 edition of Narthaki." Concept of Naayaka in Bharata's Natya Shastra" [16]Ortiz Roberto (2021).Breaking the Charts: Analysing Racialized and Gendered Sexuality in MusicVideos https://theclassicjournal.uga.edu/index.php/2021/04/07/breaking-the-charts/ [17] Shashi Prabha Kumar(1998).Indian Feminism in Vedic perspective; Journal of Indian studies, Vol. 1 [18]Courtesans in Ancient India-https://www.womensweb.in/2017/09/dancing-girls-peek-courtesans-ancient-india/ [19]Pattnaik Devdutt. 2016.The Girl who Chose-A New Way of Narrating The Ramayana. [20]Pradip Bhattacharya. "Five Holy Virgins" (PDF). Manushi. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2013. Apte, Vaman S. (2004) [1970]. The Student's Sanskrit-English Dictionary (2 ed.). Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 73. [21]Roy Ratna.2008.Book Review - Pancha Kanya: The Five Virgins of Indian Epics. A Quest in Search of Meaning. By Pradip Bhattacharya https://www.boloji.com/articles/5534/panch-kanya-the-five-virgins-of-indian-epics?fbclid=IwAR3NrZNM-txpRxJW05SCYpTUpafsa2hVrojhWJMGyGL1-MXq-KwIOU6nYwk [22]Pattnaik Devdutt (2014). Women in Hindu Mythology.The Shift Series Talk. Patel Utkarsh (2018). TEDxStXaviersMumbai - Mythology and Feminism: A Case For Subaltern Narratives [23]Barbara Stoler Miller (1977).Love Song of The Dark Lord.Columbia University Press. [24] Namita Gokhale (2018).Finding Radha: The Quest for Love [25]Debotri Dhar (Rutgers University). Radha's Revenge: Feminist Agency, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Desire in Anita Nair's Mistress. Postcolonial Text, Vol 7, No 4 (2012) [26]McBride, Andrew. "Lesbian History". Archived from the original on 2012-07-19. Retrieved 2012-10-03. Bibliography 1. K.P.Bahadur (translated into English verse).The Rasikapriya of Keshavadasa.1972 2. Priyanka Sharma. Communication of Women's discrimination & Sexuality in Natyashastra (Abstract).2013 3. Shruti Patki. Nayika,the modern woman.Narthaki - 2016 4. Parimal Phadke. Concept of Naayaka in Bharata's Natya Shastra .Narthaki - 2004 5. Debotri Dhar (Rutgers University). Radha's Revenge: Feminist Agency, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Desire in Anita Nair's Mistress. Postcolonial Text, Vol 7, No 4 (2012) 6. Jessica Frazier. Becoming the Goddess: Female Subjectivity and the Passion of the Goddess Radha (Abstract).2009 7. Sharmila Biswas. Knowing Odissi. 2008 8. Complete Gita Govinda Ashtapadi with meaning - Barbara Stoler Miller (1977). Love Song of The Dark Lord. Columbia University Press. 9. The Bhakti Movement and Roots of Indian Feminism | Feminism in India youtube 10. Utkarsh Patel | TEDxStXaviersMumbai - Mythology And Feminism: A Case For Subaltern Narratives| 2018 youtube 11. Indian Feminism | Lucknow Literature Festival | 2017 youtube 12. Devdutt Pattnaik.Women in Hindu Mythology.The Shift Series Talk.2014 youtube 13. 5 virgin/Ideal chaste women according to Indian Mythology-Paradox youtube 14. Vedic Rishikas-Shashi Prabha Kumar (1998). Indian Feminism in Vedic perspective; Journal of Indian studies, Vol. 1 15. Courtesans in Ancient India - womensweb.in 16. Feminist Views on Sexuality-McBride, Andrew. "Lesbian History". Archived from the original on 2012-07-19. Retrieved 2012-10-03. 17. Online interview Session with Odissi dancer and scholar Dr. Kaustavi Sarkar - 26th January 2021 18. Online interview session with senior Odissi dancer and scholar Dr.Rohini Dandavate - 10th February 2021 19. Telephonic interview with senior Mohiniattam exponent Momm Ganguly - 10th February 2021 20. Email interview with senior Odissi exponent Bani Ray - 14th February 2021 21. Email interview with senior Bharatanatyam exponent and scholar Dr. Janaki Rangarajan - 24th May 2021 22. Email interview with Bharatanatyam exponent Rukmini Vijayakumar - 25th May 2021 23. Telephonic interview with senior male Odissi exponent Subikash Mukherjee - 2nd June 2021 24. Telephonic interview with senior Kathak exponent Uma Dogra - 4th June 2021 25. Online interview session with senior Kathak dancer and scholar Dr. Arshiya Sethi - 22nd November 2021 26. Online interview session with senior male Odissi exponent and scholar Rahul Acharya- 21st January 2022 27. Namita Gokhale.Finding Radha: The Quest for Love-2018 28. Devdutt Pattnaik. The Girl who Chose-A New Way of Narrating The Ramayana.2016 29. Ortiz Roberto, 2021.Breaking the Charts: Analyzing Racialized and Gendered Sexuality in Music Videos 30. Ratna Roy.2008.Book Review - Pancha Kanya: The Five Virgins of Indian Epics. A Quest in Search of Meaning. By Pradip Bhattacharya 31. Dr. Harsha V.Dehejia.2014. Radha-From Gopi to Goddess 32. Dr. Rakesh Gupta.2013. Studies in Nayaka-Nayika Bheda Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will be featured in the site. |