|

|

|

|

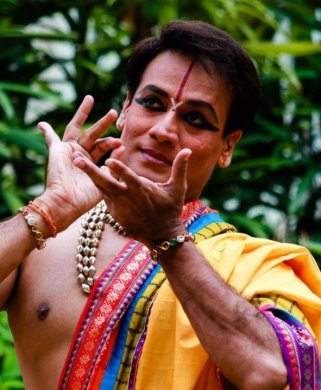

Dancer with a Midas touch - Jyothi Raghuram e-mail: jyothi.r.ram@gmail.com October 4, 2021 Teaching dance is a main source of livelihood even to those among the younger generation. More than a year and half into the pandemic, there is sense of optimism that all will be well shortly. Performing spaces are slowly opening up. Dance did not go into oblivion during those trying times. There was also an overkill. The series looks at how dancers and teachers kept their morale and their art flying high, in different ways. The series begins with an interview of Sathyanarayana Raju, the Bengaluru based Bharatanatyam dancer.  His life as a dancer was a struggle. Yet he wondered how he could use his art for philanthropy. This was ambition in reverse mode! It took him nearly two decades to establish himself as a soloist of merit, but what a presence he made eventually! His abhinaya evoked deep emotional response in the audience, grace marked his masculine nritta, his creative forays made history as significant works of art. One celebrated male dancer who has undoubtedly been propelled into stardom is Sathyanarayana Raju. One can imbibe substantially from a composite art such as dance. Sathya has grasped much, right from hisstunningdress sense to a traditionally decorated home splashed with greenery all around, to warmth and hospitality and a sense of gratefulness that has uplifted many a life. While dancers did not go berserk during the pandemic, some did go into overdrive, taking to the digital media as if for survival. The underlying reason for wanting such visibility was a point of curiosity and concern. With such bombardment of events, that began as recitals and then on to seminars and discussions, fatigue set in. Whether this medium is suitable for dance at all is a moot question. That Samskruthi and Samskruthi Shivaratri, the two festivals got up by Sathya were cancelled, was not news. What he did, or rather didn't do, during the pandemic is worthy of introspection. Maintaining a low profile during that time was a conscious choice, made difficult by the fact that dance classes were his livelihood. The need to be seen was perhaps the overriding factor for dancers to dive into the digital. However, one didn't hear anything of Sathya; it was almost as if he had gone into hibernation! Not a single video of his students was circulated outside. Sathya relates in sequential order, "My dance classes stopped suddenly. My earnings came to a halt. My major shows were cancelled. I used to help some persons financially. It bothered me that I would not be able to continue that. The pandemic changed me irreversibly. I consoled myself that everyone was facing the same situation. As the months of isolation and art wilderness increased, my perspective on life changed. Shun the 'Í', and give up this 'Í-me-myself' attitude. We don't know what will happen next. We could just vanish in a jiffy. Enjoy each day". Coming from a grounded artiste such as Sathya, these words are relevant, applicable especially in the context of an obsession for performances.  A maiden service initiative of his was for the widows of Mathura. It changed his outlook on dance; he questioned the purpose of art. Several overseas visits for workshops and performances in the 90s were planned as specific fund raisers for this. There was a time too when this aspiring dancer travelled abroad just to keep himself going financially. On home turf, solos were unavailable for male dancers. Tenacity, and the faith of his Guru, Narmada, in his prowess, gained him acceptance a few years later. "I don't think online dance is here to stay. Such festivals didn't attract me. Seminars serve little purpose. I didn't do it". Depressed during the period of lockdown, he wondered whether this was the end of dance. What was not visible to the outside world was the transformation he and his wards underwent during the pandemic. His online dance classes became opportunities for his students to experiment with short choreographic pieces, his dance practice gained thoroughness without the distraction of programs. It was a life lived together with his wards and their families, sharing daily life non-events such as recipes, hobbies, and studies, while lending emotional support to each other in the frightening, unpredictable times. "Our roles interchanged many times. My students made me tech savvy. Discussions and dissections on dance improved us". "Lost and found" isn't a cliché applicable here. Sathya lost some income by lowering his fee, given that a few parents were suddenly without jobs. Over 50 percent of his wards are from a socio-economic background that has no clue of art or can afford it. Classes for them are free. Yet in the past year, some dancers and musicians, as acknowledged by the beneficiaries themselves, received aid for medical treatment from his dance school Samskruthi -The Temple of Art, a generosity supported by the parents of his wards and friends. Sathya's famed solo Rama Katha, at Bangalore's Seva Sadan recently, was an exemplary tribute to his Guru, known for her warmth and kindness. Rs.1lakh raised again through the Samskruthi family was donated to a dancer who had lost his arm in a road mishap. It's now revival time, the Samskruthi festival in December and the Shivarathri event in March next already in line. Gratitude, in abundance, to his teacher, his extended family of wards and their parents, fellow dancers, is expressive in his ways; an incredible modesty about himself sanctifies his dance. Uncertain times made this artiste to look within. Therein lies a valuable lesson.  Jyothi Raghuram is a senior journalist and art critic based in Bangalore. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous / blog profiles to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will be featured in the site. |