|   |

|   |

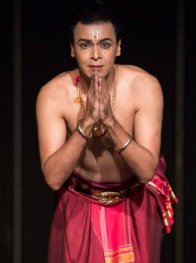

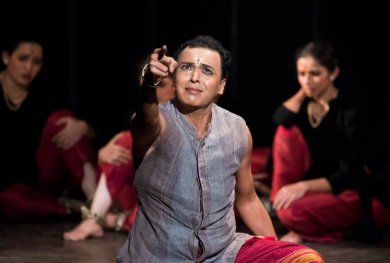

e-mail: sunilkothari1933@gmail.com Conversations with God April 17, 2018 Vaibhav Arekar's Naama Mhaane transported the audience to Pandharpur Photos: Inni Singh Performing at Delhi's Habitat Centre on the first evening of the two-day Madhavi Festival in memory of Madhavi Gopalakrishnan, mother of Bharatanatyam exponent Rama Vaidyanathan, Vaibhav Arekar and his Sankhya Ensemble transported the audience to Pandharpur in Naama Mhaane. The percussion by Krishnamurty with the playing of cymbals created magic and with chanting of Jay Jay Ramakrishna Hari by the dancers one felt that one was at the holy place of Pandharpur in Maharashtra. Being born in Mumbai and brought up there with Maharashtrian neighbors, one was steeped into abhangas of Tukaram, Janabai, Sant Namdev and others, as much as being a Vaishnava one was steeped into Haveli Sangeet and Brajbhasha songs.

Vaibhav Arekar told us that Sant Dnyaneshwar has said that Lord Vitthala had conversations with Sant Namdev only. Namdev addressed Vitthala as Vitthai. He was asked as a child to go to the temple and offer naivedya to Vitthala. We saw Vaibhav transform into a child Namdev placing plate of naivedya before the idol and begged Vitthala to eat. He cajoled him, closed his eyes and even threatened him - hitting his head on the floor, stamping his feet, folding his hands, telling him that if he does not eat, his mother would scold him and punish him. The enactment was so convincing that one felt the intense urge of a devotee experienced by Vaibhav. Sudha Raghuraman's soulful rendering enhanced that effect. Such conversations with god are rarely seen. The dancers created image of Varakari sampradaya, spreading bhakti through singing, going on a pilgrimage, with namasankirtan (recitation of the name of the lord). Vaibhav has conceptualized this production as Namdev's spiritual awakening. As a versatile dancer and choreographer, Vaibhav used the idiom of Bharatanatyam in various imaginative ways. The opening Alarippu with five female dancers and Vaibhav, slow focus of light on each dancer by Sushant Jadhav, revealed the exquisite choreography, the strength of the form with its geometric precision. The singing of Tukaram's abhang along with it went hand in hand. The chorus of dancers with white scarves, white caps, castanets like instruments and cymbals took us on a pilgrimage. Vaibhav's explanation of Namdev's journey and the parampara of other devotees, the abhangas of Janabai, Sant Savtamali, Eknath Maharaj, Sant Namdev, Sant Tukaram rendered movingly during the unfolding of the performance succeeded in lifting the spectators 'to an experiential state called bhakti.' Namdev's search for the guru, the advice given to him by the guru to look inside and search for the god from within, not like a bhramara - a bee - fleeting from one flower to another, to overcome the desires which like serpent engulfs one; the only way was shakti, energy of Naamajapa (the recitation of the name of the lord) that would bring realization and the devotee closer to god. The excruciating agony, the restlessness, the helpless state seeking the lord, were expressed by Vaibhav to the heart rending aalap by Sudha Raghuraman, and running round the stage, using pataka hasta, the desire to embrace God, moving palms all over body, the determination to seek him, by stamping feet, the use of metaphor by which the form of Bharatanatyam achieves through abstraction, this insufferable pain to merge with god were extremely touching. The series of saints has addressed the lord in various ways. Janabai treated Vitthala as a household servant to help her in daily chores, Gora Kumbhar saw god in creation of pots, Sant Savtamali in their vegetables, the onions, the crop, dancers driving the bullocks, the folk dance movements and singing merrily saying with pride that, 'we are the gardeners and farmers worshipping god.' Namdev found that society did not allow the low caste devotees even to have a glimpse of the lord. The group sequence with which Namdev moved and removing his pugree, put on a scarf and turned in a trice into untouchable devotee Chokhamela, despised by high society and physically punished, who was crushed under a wall and died seeking glimpse of the lord, was enacted with extreme devotion. It is said that Namdev built a samadhi of Chokhamela in front of Pandharpur temple and even today no one enters the temple without first visiting the samadhi. Enacting sanchari bhava in a suggestive manner in Bharatanatyam, Namdev questions the lord of the orphans - anaatha cha naatha. He who rescued his devotees like Gajaraja whose leg was caught by a crocodile and saved him with Sudarshan chakra, when would he come and help low caste devotees? The group of devotees seeking glimpse of the lord and the fear that grips them was enacted with such intensity that one would remember it for long. The finale with Brindabani Sarang in form of tillana merged in a seamless manner of chanting of Vitthala, the Bharatanatyam movements transforming into prayer, dancers with hastas suggesting form of Vishnu, dancing in circles, jumping in ecstasy as it were to reach the lord high up were a marvel of choreography. Vaibhav and his dancers achieved it so effortlessly. The use of chorus, group formations, and subtle use of Bharatanatyam technique, blending with local flavor of Maharashtrian folk movements and singing, chanting of Vitthala and Panduranga, and regional simple costumes evoked the period of bhakti movement and the living tradition of Varakari sampradaya placing Namdev in right context. Vaibhav has also been trained in theatre which he employs with ease.

Such a production is a result of excellent teamwork. Credits are due for concept, choreography - Vaibhav Arekar; research script - Pradnya Agasthi; music composition - Sudha Raghuraman; percussion arrangement - Satish Krishnamurthy; dramaturg, light, costume design - Sushant Jadhav. The musicians are: nattuvangam - Kalishwaran Pillai, vocal - Sudha Raghuraman with Megha Bhat and Gautam Marathe, mridangam and ganjira - Satish Krishnamurthy, flute - G. Raghuraman, violin - R. Sridhar. Dancers were Vaibhav Arekar, Esha Pinglay, Ruta Gokhale, Poorva Saraswat, Mrunal Madhura and Radhika Karandikar. The Madhavi Dance Festival was curated by the managing trustees Rama Vaidyanathan and Dr. Arshiya Sethi of Kri Foundation. Rani Khanam attempts a rich amalgamation of Sufi/Bhakti poetry Photos: Prasad Siddhanthi After an interval of three years, I watched vastly gifted Kathak exponent Rani Khanam, disciple of Reba Vidyarthi and Birju Maharaj, in a highly aesthetic presentation, at Delhi's Habitat Centre on 10th April. She transported the audience to the realm of abstract philosophical, Sufi and bhakti verses in an effortless manner using Kathak, revealing another dimension of Kathak which explores the Islamic aspect / concepts which merge so easily with not only bhakti but also universal truths. Dressed in white costume with white scarves studded with tiny stars, also the musicians of Abeer Band of two Muslim vocalists Shuheb and Zohaib Hasan, along with Leena Sargam, Shakeel Ahmed Khan (tabla), Nasir Khan (sarangi), Salim Kumar (sitar), and padhant (recitation of bols) by Shikha Sharma, all also dressed in white, with their soulful music, built up the mood of prayer to Khuda (god) which like a whirling dervish, Rani in several pirouettes extending her arms towards sky, appealed to the divinity for his blessings. The commentary in chaste Urdu, with occasional words in English, provided some entry points to non-Urdu speaking members of the audience. The Persian ghazal when summed up, meant that the devotee, as female, was in love with Khuda and was dancing before him. She interpreted it with sanchari bhavas, improvisations of creating cosmos. Khuda playing with sun and moon, covering sky as chunari, a scarf or a sari studded with the stars, the nine planets revolving round the sun like Parvana, the butterfly drawn to Shama, the candle, like the bee which hums around the flower and becomes a captive when the flower closes. 'Have you noticed the movement of fish in water, drops of rain falling, in each such movement I dance from slow tempo to fast one; I am dancing with abandon, in public, who pelt stones at me, and my hands are tied, and on my neck is pointed a sword that can hurt me and the blood can flow; despite that I am dancing before you, O Khuda!' This is a rough translation, but Rani with hastas and expressions created the images, drops of rain, then pouring rains through footwork and tintinnabulations of the ghunghroos. 'I surrender myself to death because I am dancing, I am in love.' The poetic imageries were accessible, if not the Persian words. The transformation through hand gestures and ecstasy was evocative leading to rasanubhuti, the aesthetic relish.

In next piece dancing to the shair, poet Hamid of Kolkata, which dealt with Khwaja Moinuddin Chisti, Garib Nawaz of Ajmer, who begs of Peer (guru) as a female devotee, as his shishya, to get glimpse of Khuda, singing 'Jara kholoji kiwadia Maharaj, boloji, rakhani padegi mori laj' (open the door, my beloved, and take me unto you), Rani expressed the anguish like a nayika in separation, her consummate artistry of abhinaya bringing alive her state - like fish separated from water and a flower from the creeper, like the butterfly rushing to a candle flame, like captive bird in a cage wanting to escape. The amalgamation of verses of Kabir, Bulleshah, Amir Khusro, Meerabai, Khwaja Usman Harooni, what in popular parlance are known as Ganga Jamani Tehzeeb, the confluence of rivers Ganga and Jamuna, found a felicitous expression in Rani's dance, evoking the essence of those upama, poetic similes. The devotee raises her hands in Ibadata, prayer. The improvisation was enacted for raindrops, the creation of the world, and 'when the drops fell on me I realized,' the devotee says, 'there were seven notes, seven colours. O Khuda, you coloured my chunari, sari, in black ink colour, removed the black and washed all my unhappiness. With your element by which my body is created, I shall abandon it and will merge with the soil.' Like, as Bulleshah sings, 'I shall play Hori singing aloud Bismillah Bismillah, Ilahi Ilahi Ilahi,' the entire auditorium was filled with the chanting of Bismillah Bismillah and Ilahi Ilahi. So powerful was the singing by the musicians, their heart wrenching appeal to Khuda like azaan, prayers by Muslim devotees in a mosque. The music of Qawwali genre, the chorus et al generated the devotional mood to which Rani with her endless pirouettes danced ending the performance in a trance. No wonder the audience stood up and gave her a standing ovation. The entire presentation created a magic, the like of which I do not recollect having experienced in recent years. As a tribute to the two vocalists Shuheb and Zohaib Hasan their special brief musical concert was presented after the dance, which won them great applause. Indeed performance by Rani Khanam and these two musicians was the highlight of the entire presentation. The musicians brought the dance alive with their wonderful accompaniment. When so much thought was given for preparation, it would have been wonderful to have program notes, preferably in English, to follow what was unfolding on stage. I am sure in future Rani Khanam, the ace compere that Sadhana Srivastava is, and their associates would make a note of it, specially since the verses are in Persian and Urdu languages. To see Rani mobbed by her admirers after the show was heartening. That Kathak has this other dimension was brought home in artistic manner keeping the spirit of Kathak intact.  Dr. Sunil Kothari is a dance historian, scholar, author and critic, Padma Shri awardee and fellow, Sangeet Natak Akademi. Dance Critics' Association, New York, has honoured him with Lifetime Achievement award. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |