|   |

|   |

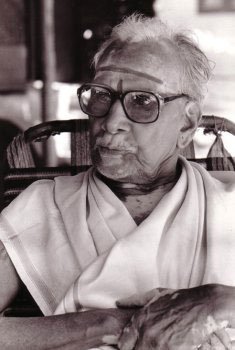

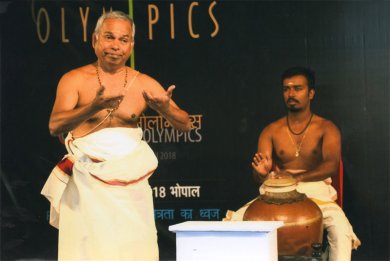

e-mail: sunilkothari1933@gmail.com 8th Olympic Theatre Seminar on Natyashastra Photos courtesy: Bharat Bhavan April 7, 2018 During more than two months duration 8th Olympic Theatre Festival was organized by National School of Drama (NSD) and Ministry of Culture at several cities within India, with presentation of plays in various languages along with seminars on various aspects of theatre. One which was organized at Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal was on different aspects of theatre in relation to Natyashastra. Many leading scholars, practitioners, directors, dancers, musicians, authors and critics were invited to participate for two days on 23rd and 24th March, to discuss and deliberate on practice of Natyashastra. I was invited to present my paper and chair the session on Practice of Natyashastra: In perspective of Rasa. The Rasa Sutra as mentioned in the sixth chapter of the Natyashastra refers to bhava, vibhava, vyabhichari bhava and with their confluence takes place the rasanishpatti. The aphoristic formula for the issuance of rasa as given in Natyashastra is that the rasa issues forth when vibhava, anubhava and vyabhicharibhava are appropriately blended. Natyashastra continues to remain a main semiotic text for plurality of various dance and dance-drama forms of India. In practice, the Rasa Theory applies more in principle to the performances of classical dance forms, which are eight in number with inclusion of Odissi, Kuchipudi, Mohiniattam and Sattriya dances to well established forms of Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Manipuri and Kathakali. However, the Natyashastra principles are seen in terms of practice in dance drama forms like Koodiyattam, Kathakali and Krishnattam of Kerala, Kuchipudi dance dramas of Andhra Pradesh, Bhagavata Mela Natakams, Kuravanji dance drama forms of Tamilnadu, Yakshagana of Karnataka and Sattriya dances including Bhaona and Ankiya Nat of Assam and also Therukoothu of Tamilnadu.  Ammanur Madhava Chakyar Whoever has seen the performances of late Ammanur Madhava Chakyar in Koodiyattam knows how abhinaya as expounded in Natyashastra is reflected in its exposition. One recalls his unforgettable performance at National School of Drama at Abhimanch a few years ago. With help of his students, he sat on an 18 inch wooden stool enacting the event of Kailasoddharana from the play Thoranayuddham. Ammanur Madhava Chakyar stared at the torch in front of him with unblinking stare as if in deep contemplation. But to the wonderment of all, in one purposeful moment he suddenly stood up on the stool and began to enact the scene of Ravana lifting Mount Kailasa, where lived Lord Shiva and his consort Parvati. With extraordinary netrabhinaya, he looked down with eyes wide open. The pupils, one felt went down for a long time. The illusion was amazing. One was as it were watching the valley without end. Then he raised his eyes upwards, the pupils seemed to be rising higher seeing the peaks of Himalaya rising above, almost touching the sky. Then one saw him enacting the role of Ravana, lifting the mountain and throwing it up and catching it like one would a ball. For next half an hour or so, the way he enacted the scene was mind boggling. The rasanishpatti the guru created mesmerized us. The relentless practice using the principles outlined in Natyashastra on how to control breathing, use the eyes, expressions on the face, the eyebrows, all helped the guru to create that illusion and rasa in the audience. One was also afraid that the frail guru would fall. But he had with his artistry created before one's eyes Kailasa Mountain where none other than the gods lived! The element of natya, the drama was taking place with vocabulary of gestures and movements. The Natyashastra texts prescribe the hastas, the hand gestures, and mukhajabhinaya, facial expressions for depiction of the story, the dramas. It is seen more pronounced in Koodiyattam. One sees it also in Kathakali when enacting choliyattam, using the manodharma, improvisation, sancharibhavas which weave a world of magic. Those who have seen Kapila Venu's Koodiyattam performances and have taken lessons from G. Venu at workshops at NSD would know how principles of Natyashastra in practice are employed. Recently in Delhi, I saw Piyal Bhattacharya's Bhaanaka, Marga Natya performance, which also traces origins of natya in Natyashastra and his attempts at reconstruction of earlier musical instruments and musical traditions. I would like to draw attention to vyabhichari bhavas, also called sanchari bhavas, which are transitory. They accompany the main bhava. Its main aim is to heighten the taste of the sthayibhava. More appropriately, it may be called 'a visitant bhava.' Some feelings are not concordant with a particular emotion. For instance, feeling of anger does not quite agree with the emotion of love. If however, one is jealous of one's lover because of unmistakable signs of infidelity, the feeling of anger comes as a visitant. This anger and the anger toward an enemy are totally different .While the abhinaya of anger for the enemy is anubhava, that for the lover out of jealousy is vyabhichari bhava. In Kathakali dance drama Nala Charitam, when Nala is banished to forest and his wife Damayanti goes with him, they undergo great hardships. Nala is unable to feed Damayanti, whenever he brings a catch of fish. Damayanti had a boon of sanjivani vidya. Therefore, when Nala brought dead fish, the moment Damayanti touched them, they came alive and slipped from her palms. Nala was most unhappy. He decided to leave her, hoping she would return to her father. He left her one night and a hunter saw her and was enamoured by her beauty. But before he could make any advances, Damayanti ran away and managed to reach her father's palace. Meanwhile, Nala was bitten by a serpent and could not be recognized as Nala. As Bahuka, since he knew the art of driving chariot at the speed of wind, he took service as a charioteer in another King's place. The King liked his art of driving chariot and readily employed him. In separation Damayanti requested her father to announce her swayamvara. She knew that knowing about it Nala would somehow return and there will be union again. The King in whose service Nala was working as a charioteer on learning about Damayanti's swayamvara, asked Nala to get ready and proceed to King Vidarbha's kingdom to win Damayanti. Nala as Bahuka was most distressed, but obeyed and arrived with great speed to Vidarbha's city. But when they entered the city, they stopped for a while. They saw an amusing incident.  Kalamandalam Krishnan Nair In a pond, a fisherman was repeatedly throwing his net to catch fish without luck. Meanwhile he listened to the pleasant laughter of beautiful women from above the seven story mansion. And lo and behold, they saw the miracle. Those beautiful women with their eyes of the shape of fish were giggling. The reflection of their fish like eyes was seen by the fisherman in water and he had mistaken them to be fish! No wonder he could not catch what he wanted. I had seen this enactment by legendary late Kalamandalam Krishnan Nair many years ago. But I still vividly recollect it in my mind's eye. Such are the amazing sanchari bhavas, which Kathakali artists can perform using imagination and create rasanishpatti. The appeal of Indian dances and theatre lies in the fact that being highly evocative they are deeply poetic. The poetic quality is much watered down if the sthayibhava is not fully developed. No doubt, dance and theatre are an applied art. The dancer/ actor therefore needs to know how to and what to apply. But it is understanding of the rasa theory that can give him the right answer to the question, 'how to apply.' India holds that in the field of art 'rasameva jayate' meaning 'it is only rasa that is celebrated.' This is known to all performers of dance and theatre. With the passage of time the art of abhinaya in contemporary theatre has changed. Vachika has changed; acting known as Natyadharmi and Lokadharmi has changed. Despite that, the rasa theory has remained valid more so in application of classical arts. I have often wondered about the expression of bhaya - fear - in context of novels of writer Kafka. His characters experience fear in normal life and critics have termed it as 'Kafkaesque fear.' I feel the bhava of bhaya is expressed in the term 'Kafkaesque fear.' The modern theatre which we witness also shares the principles of Natyashastra. But it appears to me that in practice of rasa, the Rasa theory applies more to classical Sanskrit drama and dance dramas and also in some of the folk theatre forms like Therukoothu of Tamilnadu.  G Venu Since G.Venu was the next speaker, I requested him to demonstrate his presentation with abhinaya. A versatile Koodiyattam exponent, a disciple of Ammanur Madhava Chakyar, G. Venu explained the importance of breathing, then showed tremendous concentration with eyes looking straight towards audience. He mentioned that the training given by traditional teachers in Kerala and the art of Koodiyattam demanded on part of actor to master the art of breathing and have concentration. The other expressions, the usage of eyes, eyebrows, mukhajabhinaya, the various bhavas, the hastas to denote the status of the person, contextually as king, or a servant can be evoked with practice. Of course the text often dictates and the elaboration with manodharma plays an important role. He gave examples of Ramayana being staged for more than a month. So many plays in Sanskrit performed in Koodiyattam take a long time. Even today in Kerala Koodiyattam performances in terms of festivals are performed for a several days. K.S. Rajendran spoke of Sanskrit theatre and the Rasa depiction. He mentioned that the use of classical dance was helpful to evoke the expected Rasa. He screened an excerpt of Vikramovarshiyam play in which a group of dancers participated. The dance technique was able to further enhance the scene and the incident of Urvashi's dance seen by devas and also by King Pururava could be produced more effectively. The second session was on topic of Natyashastra in perspective of technique. Bharat Sharma chaired the session. The other participants were Bharatanatyam gurus and performers Dr. Sanddhya Purecha and Vaibhav Arekar, both from Mumbai and Chandra Dasan from Kochi. Bharat Sharma expressed his own issues with technique and study of Natyashastra. His father late Narendra Sharma was a choreographer and a member of Uday Shankar's troupe at Almora. After parting with Uday Shankar's troupe when the troupe was dissolved, Narendra Sharma settled in New Delhi and taught dance at Modern School. Bharat studied dance from his childhood from his father. Narendra Sharma followed Uday Shankar's style and his own creative style. There was not much in terms of study of Natyashastra. Therefore Bharat posed a problem that he had no exposure to Natyashastra and its application in terms of Rasa and technique. He mentioned that after listening to Shri Kamalesh Dutta Tripathi, he got a sense of the vastness and relevance of principles of Nayashastra. He got up and touched the feet of Tripathi, saying that barring his parents as guru, and Mayurbhanj Chhau guru Krishna Chandra, he had not touched the feet of any one as a guru. He also said that learning dance like Mayurbhanj Chhau where technique was so unusual that he was quite perplexed. Mayurbhanj and Seraikella Chhau forms use the leg movements to suggest daily chores like preparing cow dung, putting tilak on forehead, swimming, moving, jumping like a deer, et al with leg movements. The communication was also achieved by the technique evolved by his father but there was not much of an awareness of the Natyashastra as technique. Dr Sanddhya Purecha, a disciple of Acharya Parvati Kumar, mentioned how with the technique of Natyashastra her guru had composed in terms of enactment of Abhinaya Darpana. All the shlokas of Abhinaya Darpana, the viniyogas of the hastas, charis, sthankas etc., were successfully used in performing a Natyashastra text like Abhinaya Darpana. It is fully recorded and is in the archive of Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. For a dancer, guru and a choreographer the technique of the Natyashastra is most relevant. Vaibhav Arekar, a disciple of Dr. Kanak Rele and also Thangamani Nagarajan, spoke of technique employed for presentation of say a classical dance form like Bharatanatyam. The technique is so well defined and practiced though Bharatanatyam is mainly performed by female dancers, with a theme wherein a nayika is pinning for her beloved. If performed by a man such expression would look incongruent. But technique helps the male dancer to transcend the gender. As a bhakta he loses his gender and evokes yearing to merge with the lord. Vaibhav demonstrated one stanza from a varnam and explained that bhavas and interpretation technique of Natyashastra, resolves such issues. He has also received training from theatre director late Chetan Datar. Therefore he could distinguish the technique used by theatre director and one used for classical dance. In terms of abhinaya he could utilize both Lokadharmi and Natyadharmi to his advantage. Chandra Dasan is a director from Kochi and is well versed both in Natyashastra and forms like Kathakali dance dramas and Koodiyattam. However, he felt that there is enough scope for a contemporary director to use Natyashastra principles for technique according to the theme.It would have been interesting if any excerpt of his play was used to illustrate his viewpoints.

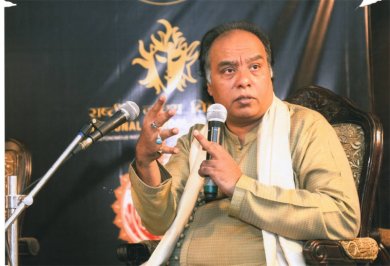

Wasifuddin Dagar  Kalamandalam Rama Chakyar On account of change of schedule, I missed the session on Natyashastra in perspective of Kaku, chaired by Rita Ganguly, a former professor in movements in NSD and a renowned vocalist, disciple of Siddheshwari Devi and Begum Akhtar. Rita Ganguly and Wasifuddin Dagar had presented by singing the concept of Kaku in music. Next day at the airport, we met scholar KK Gopalakrishnan who along with Kalamandalam Rama Chakyar had presented Natyashastra in perspective of Kaku. Sangeeta Gundecha had spoken in Hindi on explanation of Kaku in vachikabhinaya. I requested both of them to send me their abstracts of papers. They are extremely important for the practioners of theatre as Kaku is used mostly in vachikabhinaya. I am quoting from KK Gopalakrishnan's paper as Sangeeta's paper also refers mainly to the same topic. Natyashastra (Chapter 19 - Vakya Vidhanam) divides Kaku into two - Sakaamksha and Niraakamksha. It may be understood that the two fold Kaku is the intonation - swara viparyayam, which is the rise and fall of the voice in a speech/dialogue. While sentence without complete meaning comes under Sakaamksha, sentence that is complete with meaning is known as Niraakamksha. The literal meaning of Kaku is tremulous voice resulting from fear, grief, interrogation mark, a secret, tongue etc. As per the prescriptions of NS what we understand is that Kaku is the technique of achieving the changes in the meaning through intonation, including an opposite meaning. Also, considering the facts that Koodiyattam follows the prescriptions of NS in several aspects - it is among the Indian performing arts traditions the acting of which stands more closely to a few of the directions of NS - and also at times questions or overlooks the instructions of NS, and considering the limitations in practical application, one may conclude that it will be difficult to follow the rules regarding Kaku along with other related prescriptions of Vakya Vidhanam exactly in any sort of practice. Additionally, Koodiyattam is not a form based on the prescriptions of Natyashastra. Hence, only a generalized view may be possible. Here it is very important to understand that in stylized forms the usage of Kaku is not exactly as prescribed in the Natyashastra, because the significance is for the non-realistic structure of the form; whereas, in forms of Lokadharmi/those with normal usage of dialogues, Kaku is more or less explicit and direct. An example for the latter is the act of Vasanthaka in Manthrankam Koodiyattam play that highlights Lokadharmi/realistic elements in a stylized/non-realistic form. One may dispute about its practical applications as the organic elements of each land have its own influence in the way a word is pronounced or an emotion is expressed. Only through a few practical examples one may understand this. In these backdrops, we may look at how the shlokas/dialogues are delivered and enacted in Koodiyattam. In Koodiyattam one may also see that some of the verses and its intonations are with dual meaning; some may be even negative. Example of Sakaamksha: Hanuman to Ravana - Choorni (sentence): 'Bho Rajan api kushaleebhavaan?' Here no verb is used and its literal meaning is - 'Oh Raja, are you fine?' Contextual meaning - intention is - since his son Akshakumaran was already dead, Ravana may not be feeling happy. And the hand gestures subsequently shown are whether rituals connected with the funeral of Akshakumaran were over. Example of Niraakamksha: Act of Vasanthaka in Manthrankam play: In Prakrit it is: 'Aaya dehi chande samaaydaani sarva nakhathani' In Sanskrit it is: 'Aagathe hi chandre samaagataani sarva nakshathrani' Meaning: When Chandran (moon) came, Nakshathras (stars) too came. KK Gopalakrishnan later explained how Kalamandalam Rama Chakyar used hastas without speaking to suggest the other meanings. I have quoted this briefly for readers who are practitioners and but do not know about Kaku from the Natyashatra as used in performance, would understand how in practice it is used while performing.

The last session was on Natyashastra in perspective of writing chaired by former director of NSD, well known author Prof. Devendra Raj Ankur. The participants were Rama Ratan Bhargava, Yogesh Tripathi and Abhiram Bhadakamkar. Writing plays as per the Natyashastra perspective was discussed by the speakers with their own experiences. However this session also was more in terms of writing plays in mainly Hindi language and since I was not conversant with literary Hindi language plays, I could not follow the discussion. The seminar papers are to be published in a book form which will be a valuable source of information for students of theatre. NSD deserves congratulations for organizing this two day seminar with so many scholars and also from field of classical dance.  Dr. Sunil Kothari is a dance historian, scholar, author and critic, Padma Shri awardee and fellow, Sangeet Natak Akademi. Dance Critics' Association, New York, has honoured him with Lifetime Achievement award. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |