|   |

|   |

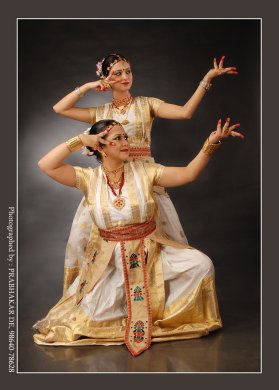

e-mail: janakipatrik@gmail.com Dance Criticism - A few principles for writing about Indian classical dance November 4, 2021 In her article MOURNING MY PROFESSION published on 29 October 2021 in the VILLAGE VOICE, eminent American dance writer and critic Elizabeth Zimmer wrote a eulogy for the demise of dance criticism. Ms. Zimmer's thoughtful observations prompted me to revisit some thoughts I had about writing dance critiques of classical Indian dance performances. I had originally organized my thoughts into an essay written in 2014, which I have revised considerably for this article.  Elizabeth Zimmer I started watching classical Indian dance when I was in my first year at Swarthmore College. Two performances by the greatest of the great Indian classical dancers - one by Birju Maharaj in 1963 and the second by Balasaraswati in 1964 - drew me into a lifetime of studying, performing, choreographing and writing about Indian dance, especially Kathak. Now, after almost 60 years of watching classical Indian dance, I have many thoughts about excellence in technical execution, choreographic clarity and conceptual creativity in the many groups and soloists whom I have seen on American and Indian stages, and most recently on virtual platforms. But I do not write dance criticism - I do not critique my colleagues. However, I do have some ideas about what it takes to be an informed, conscientious and self-aware dance critic. I also have ideas about nurturing classical Indian dance in the United States through informed viewing and well-balanced dance criticism. I take as my gold standard the critiques written by Nala Najan and published in SRUTI, the Chennai-based dance magazine founded and edited - during Nala Najan's writing tenure - by the late Dr. Pattabhi Raman. What Nala Najan's critiques were NOT were flippant, short and arrogant expressions of individual opinion, written as if "the word of the lord from on high". Instead, Nala Najan's reports were written in the form of extended essays about the style, the literary sources of the poetry which was performed, the music, the artists' costuming and other illuminating details. Above all, Mr. Najan's writing exhibited his respect for the creative process, and for the history and challenges of performing classical Indian dance in America. Readers learned something about the dance and its American context, not simply about one person's subjective opinion. I think that the age of the Internet, with easy access to email, FaceBook and Twitter-cum-twaddle, encourages short messages, not even written in full sentences, and with abbreviated spelling and distracting emojis.These text messages often exhibit no effort on the part of the writers to organize their thoughts into paragraphs which express fully-developed ideas. This stream-of-conscious writing encourages the reality show democratization of thought, as if every opinion is as valuable as every other, whether based on fact and research or not. Moreover, just as audience attention span has shrunk, so too has reader attention span shrunk. Many challenges face dance criticism, which today's general readership expects to be high on photos and short on words. I acknowledge some of the factors mitigating against good dance criticism - "good" defined as the kind that contributes to knowledge rather than gossip and PR. Despite all these factors, I would still insist on some fundamental principles should be followed by conscientious writers in this special field which translates movement into words, balancing the objective against the subjective elements contributing to expository writing. Some of these principles would apply to writers who publish dance criticism in both India and the United States. 1. Critics should write with self-awareness of the limits of their own knowledge about the subject. Certain styles of Indian dance exhibit more of the abstract structural perfection, which American audiences can "read" and enjoy as differently-costumed variations of familiar western forms. Some American audience members may feel less comfortable - and in fact feel alienated from - those styles which depend heavily on nuances of sringaar abhinaya (romantic/erotic acting) and texts in regional Indian languages. Dance criticism should acknowledge the limits of the writer's knowledge and comfort zone. Yes, of course no single person can know everything to be known about the dance s/he is viewing. But this lack of perfect knowledge should create a humility toward the performance and the performers, rather than an annoyance, which colors a review based on the writer's biases. In addition, certain elements of a particular style may appear more "folksy" than others. For example, Kuchipudi, and Kathak still exhibit elements from their folk past: Kuchipudi moves with a bit more bounce in the step and exaggeration in abhinaya than does the more geometrically angular Kalakshetra Bharatanatyam style. Kathak includes multiple exhibitionist, stop-on-a-dime turns, as well as the informal practice of speaking mid-performance to accompanying musicians. But the bounce and the "circus tricks" and the informal, onstage instructions to musicians are all included in the canon of these classical styles. It would be incorrect to conclude that these elements prove these styles less "classical" - or worse yet, commercial. These examples raise general questions about the privileging of one style over another in judging excellence. An American critic whose history of viewing dance does not include many hours of watching Indian dance performances, and whose reading does not include many books on Indian dance and literature, should not be making categorical judgments about authenticity and excellence in classical Indian dance styles. If that critic has been raised on a visual diet of ballet and modern dance, then his/her lens for judging excellence necessarily refracts Indian dance with a measure of personal distortion. Those styles conforming most closely to Western expectation of polished structure and execution are judged "classical", as against other forms less "cleansed" of their "folk" elements and other stylistic idiosyncrasies. 2. Critics should write with an awareness of the on-going dialogues - both in Indian and western scholarly circles -- about the designations "classical", "folk" and "ethnic" dance, particularly when they write about dance styles originating in cultures outside their personal knowledge and cultural intuition. There have been many scholarly discussions about the incorrect designation of western ballet as "classical" and of non-western dance (including Indian classical dance) as "ethnic". A seminal work by scholar Joann Wheeler Kealiinohomoku, published in 1970 and entitled "An anthropologist looks at ballet as a form of ethnic dance", demolished the outdated, long-reigning and formerly unspoken assumption that "classical" should be a designation reserved for Euro-centric ballet, and that all other forms of dance, particularly non-western, should be designated "ethnic" or "modern" or "folk". Now, over 50 years later, this insight is old news. Dance writers and adjudicators are quick to acknowledge that classical Indian dance styles must be considered just as "classical" as ballet, and that the folk roots of many mature styles of world dance should not diminish their status as classical dances. But what may not be so readily acknowledged is the degree to which this issue influences our perception of Indian dance styles still in the process of emerging and evolving from their folk-theater and temple pasts. Odissi went through this phase, when its technique and repertoire were transposed and trans-created from its mahari and gotipua roots. Some of the ritualistic bhakti driven practices from its temple heritage, as well as acrobatics from its gotipua boy-performer troupes, are still included in classical Odissi performances rather than being excised for their lack of classicism. Nevertheless, the form has been modified to the extant, that it now meets Western expectations of a polished, "classical" presentation. The same cannot be said yet about Sattriya dance, which has only recently been recognized as the eighth style of classical Indian dance. Debates still rage about performance practice, authenticity and appropriation viz. Sattriya practitioners, and these debates exemplify the difficult issues, which even the most conscientious dance writers must negotiate regarding the defining markers and boundaries of "classicism". The following example illustrates Principle #2 - that is, writing with an awareness of ongoing dialogues about stylistic designations in classical Indian dance.I have written with considerable detail, because I think this example demonstrates the critic's lack of awareness of this issue, which is essential in writing responsible critiques of Indian classical dance performances. Given official designation in 2000 as India's eighth classical dance style, Sattriya is still in the process of finding its "classicism" within the Sattriya dance vocabulary, which developed during a 500 year period in secluded monasteries located in remote northern Assamese villages and on Majuli Island in the middle of the Brahmaputra River. As this form emerges from the monasteries in which it was performed by celibate monks, and where it developed as a theatrical form intended for worship and for propagating the founder's religious and social beliefs, modifications being made for modern theatrical presentations have altered the form and its message. Some people question whether these modifications render modern Sattriya "inauthentic". The question of whether its current, predominantly female practitioners a priori render modern performances "inauthentic" is joined by a host of other questions. The transposition of Sattriya dramas from the sacred satra to a modern stage; the acceptable vocabulary of facial abhinaya in a dance style whose temple practitioners traditionally wore masks; expansion of the repertoire to secular topics, and many other aesthetics and stylistic issues have still not settled into a general consensus on the elements of classical Sattriya. Some Sattriya dancers have found a solution to the authenticity debate by "bharatanatyam-izing" Sattriya. Will this hybrid become the accepted "classical" norm, partly because it best fits the lens of urbanized and westernized audiences? An even more relevant question is why a western dance critic should question whether a performance presented by one of Sattriya's most senior Assamese-born, but now American-based, artists adequately "exemplifies" the style. Why should a western critic claim a right to decide authenticity, creating a new form of colonial chauvinism in critical writing?  Alastair Macaulay In his 18 August 2014 New York Times review of NAVATMAN's Drive East Festival, Alastair Macaulay wrote: " .... Sattriya ... was new to me. I'm by no means sure, however, how well it was exemplified here. ... Like another of the eight classical styles, Manipuri (from the neighboring state of Manipur), Sattriya looks Indian even while suggesting several different cultural qualities and different rhythms. But is it as guarded and polite as the three women of the [Philadelphia-based] Sattriya Dance Company made it look? Their final number on Saturday was about the Brahmaputra River, which is central to Assam; but the vocal and orchestral sound seemed awkwardly like Europop." Review Had Mr. Macaulay researched the life and work of the musical accompaniment's composer and singer, Bhupen Hazarika, he might have chosen his words more judiciously, instead of dismissively describing Mr. Hazarika's song MAHABAHU BRAMHOPUTRA as "awkwardly like Europop." A beloved composer who popularized his native Assamese music, glorified the beauty of Assam's nature and celebrated universal brotherhood, Bhupen Hazarika was known nationally through his songs and his performances of them for Indian cinema. The program notes stated that the choreography was set in Sattriya style, but not specifically classical; that Bhupen Hazarika's music paid tribute to the diversity of the land through which the Brahmaputra River passed; and that this performance was a tribute to the recently-deceased composer, Bhupen Hazarika. To those who take the time to research the history of Sattriya, it is self-evident why this Sattriya performance honored Bhupen Hazarika. He was responsible for Sattriya's designation in 2000 by the Sangeet Natak Akademi (India's National Arts Akademi) as India's eighth classical dance style. Mr. Hazarika's protean creativity was recognized by many awards from Indian national arts organizations, including the Padma Vibhushan, India's second-highest civilian award (posthumously awarded in 2012) and the coveted Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award (posthumouslyawarded in 2019). Those who know anything about Indian arts would recognize the names of the six other artists who have received this rare award for their service to India in the period since the award was created on 2 January 1954 - Bhimsen Joshi, Bismilla Khan, Lata Mangeshkar, Ravi Shankar, M.S. Subbulakshmi and Satyajit Ray. Bhupen Hazarika is the seventh artist in this stellar and very short list of Bharat Ratna awardees. In this light one sees that in writing so dismissively about Mr. Hazarika, Mr. Macaulay insulted the Indian government institutions which confer honors, and the Indian people whose love for their most esteemed and well-known artists confers their own assessments of honor, gratitude and respect.  Sattriya dancers Madhusmita Bora & Prerona Bhuyan The ethical dance critic - particularly one nursed on the milk of western ballet - should recognize his/her artistic prejudices and write from a more carefully-researched stance. One hopes that Mr. Macaulay attended World Music Institute's 22 April 2018 presentation of "The Dancing Monks of Assam and Sattriya Dance Company". Introduced by an informative slide-lecture by Rajika Puri, founder and curator of the DANCING THE GODS Festival in which the "Dancing Monks" were included, the performance revealed the restrained drama of the Sattriya form. One hopes that Mr. Macaulay would reassess his use of the obliquely critical words "guarded and polite" to describe Anita Sharma, Madhusmita Bora and Prerona Bhuyan's performance in his 2014 review of the Drive East Festival. I hope that he noted, instead, the restrained passion of the monks' performances, and the respectful ecstasy exhibited by Ms. Bora and Ms. Bhuyan in this 2018 festival. Performing on the same stage as the monks, but never at the same time, the two women honored the strictures of this traditionally all-male, sacred form. In light of the success of the "Dancing Monks" United States tour, and its appreciation by initiated and uninitiated audiences alike, the question of whether its producer, Ms. Bora authentically "exemplifies" Sattriya dance is as insulting, as its answer is self-evident. 3. Critics should consider their own subjective lens. For example, - has the critic been coached in unfamiliar Indian dance forms by a primary source person to whom the critic gives credibility because she/he owes allegiance for perks such as invitations to parties, introductions to special people, trips to India, etc.? And has that source person transmitted personal prejudices in the guise of objective fact? - and similarly, has the critic been prejudiced against a particular performer or group by a desi (read "authentic") informer, whose power-plays within the Indo-American dance world are being transmitted as if objective judgments? - does the critic apply prejudicial criteria of authenticity, unacknowledged even to him/herself: for examples, that only Muslims can authentically perform an Urdu ghazal and only Hindus can authentically perform a Sanskrit prayer? And most damaging for a dance style's designation as an international form, does the critic base evaluations of a dance performance's authenticity on purity of ethnic origin? Where then is the "suspension of disbelief" on which all performing arts depend, and the magical transformations by makeup, costuming, good training and stage lighting? And in a giant step backwards for the democratization of international arts, should dancers of non-Caucasian ethnicity be banished from the ballet stage? 4. Critics should write responsible and responsive critiques, judging and supporting artists from both the Indian homeland and the American diaspora. As increasing numbers of home-grown classical Indian solo and group performances in the United States reach professional standards of excellence, the possibilities for them to be presented in prime United States venues have increased. But it is still the norm in many venues for only the top classical Indian artists still based in India to be booked into the highest paying and most prestigious mainstream venues and performance series. Since many Indo-American artists who teach and perform classical Indian dance return regularly to India and to their gurus, the possibility of maintaining high standards of excellence has become one of personal drive rather than geographic location. Dance, as a living art, evolves in part by absorbing outside influences. While it is not the function of critics to address such discrepancies, they should curb the knee-jerk reaction that "from India" is necessarily better than "from the United States". A big factor in this scenario is economic. If many of the big fees go to artists from India, whose pay is multiplied by its conversion to rupees, only a pittance remains for the American-born professional classical Indian dancers with which to pay their American expenses. In theory Indo-American dancers should be supported by grant money available from local and national arts organizations, but this type of funding has been cut drastically, including from the National Endowment for the Arts' budget under Ronald Regan's administration in 1986, and in the years since September 11, 2001. Moreover, adequate and informed press coverage plays a vital role in legitimizing American-grown artists and their groups and schools. If big media reviews are mostly reserved for big name artists from India performing in high visibility venues, the possibility for home grown Indian dancers and their companies to develop to professional levels is diminished. 5. The critic should read the program notes and listen carefully to the on-stage introduction of a performance. Arriving late and being ushered to the best seat in the house no doubt confers honor on dance critics. But it leaves little time for them to read the essential guides to the performance they are about to see. The American critic can learn a great deal by reading the program notes, which are often written by the choreographers themselves. The notes indicate what the artists are trying to say through their choreography, musical accompaniment and dance acting. Program notes often include translations or summaries of poetic texts, bridging any language barriers the American critic might encounter. And they narrate any religious or mythological details in the relevant story line. It is surprising how many critics give credence to the remark attributed to the great modern ballet choreographer George Balanchine, "There are no mother-in-laws in ballet", as if it were a prescription for viewing all dance, irrespective of its origin. But the fact is that there ARE mother-in-laws in classical Indian dance, most famously Ram's step-mother and Sita's step-mother-in-law Kaikeyi in the pan-Indian epic RAMAYANA. Viewing classical Indian dance, as if it must be self-referential and every movement must speak for itself with no contextual background, is to impose a modern Western aesthetic on a non-western dance form. Viewing classical Indian dances as complete unto themselves, with "no mother-in-laws"; the critic would see only moving abstract pictures, their surface beauty devoid of its distinctly non-western storytelling context. On the contrary many classical Indian dances require the viewer to "read" movement as a rich narrative text. It is sad that many readers of dance reviews, whether they saw a particular performance or not, will give credence to a critic's words. They will certainly be less likely to attend a performance by artists who have received poor reviews, hesitating to spend time and money to attend a classical Indian dance performance which has been judged inauthentic, or technically and choreographically substandard. And the dancers will have this misguided review following them on the FaceBook, Twitter and twaddle trail. Such is the power of the written word. Addressing this power of the written word to diminish the eloquence of the dance itself, Dr. Uttara Coorlawala -- dancer, scholar, dance writer, performance curator, recipient of the 2011 Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar Award, India's highest award in the performing arts -- wrote, "As dance scholars negotiate academia, it becomes crucial to resist the pressure to privilege the written word over oral/aural transmissions of bodily information. The politics of the body silenced, while text continues to speak for the body, denigrates the place of dance in society." - Dance Research Journal 32/1 (summer 2000) 6. Before reviewing a performance which blends a classical Indian dance style with a non-Indian dance or music form, reviewers should be sufficiently familiar with the original Indian dance style to judge how much, and to what degree of success, the hybrid dance has detoured from the original. I think this principle is self-evident. All eight classical Indian dance styles have joined the global circus. Long gone are the decades, centuries and millennia during which manifestations of culture, including language, music, theater and dance, could develop in isolation from influences which might "pollute" their purity and authenticity. The speed at which cultural artifacts collide, explode and fuse is increasing at warp speed. Whether the fusion creates "confusion" or a stunning synergy depends on the knowledge, imagination and integrity of the creative artist. Often, the artists who break the rules are those who are celebrated, fulfilling the popular demand for ever-new, ever-more exciting dances. Writing knowledgably about these cultural collisions demands intelligent discrimination. In such times as these, following some simple principles for responsive and responsible classical Indian dance criticism demands a lot from the dance critic: humility and intellectual curiosity in viewing the unknowns in dance, consideration of the physical and mental demands of classical Indian dance, tempering of flash judgments, understanding of the compromises made due to financial constraints, and, above all, informed viewing. This is not too much to ask of critics, whose words potentially reach millions. © Janaki Patrik, 4 November 2021  Trained in both classical Kathak dance (Pt. Birju Maharaj, beginning 1967) and Merce Cunningham modern dance technique (1971 to 1978), Janaki Patrik has choreographed thirty full-evening productions and numerous shorter works exploring an eclectic range of poetry, mythic storytelling and music. She is the Artistic Director and Founder (1978) of The Kathak Ensemble & Friends/CARAVAN, NYC. A dedicated teacher, Janaki has trained dancers to perform an extensive repertoire of classical Kathak, as well as her new choreography. Teaching and performing in inner-city schools through Urban Gateways/Chicago and Young Audiences/New York for forty years, Janaki has embodied the power of dance and music to communicate the interconnections of all cultures. Post your comments Please provide your name along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |