|   |

|   |

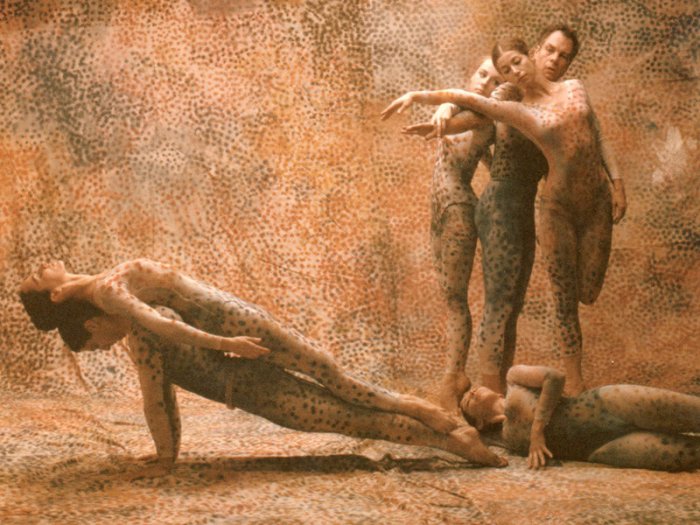

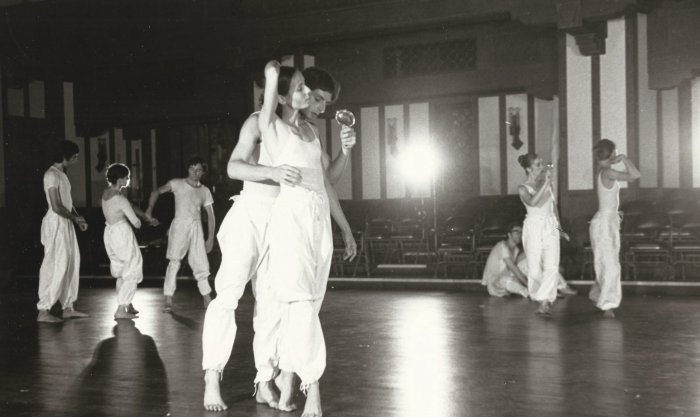

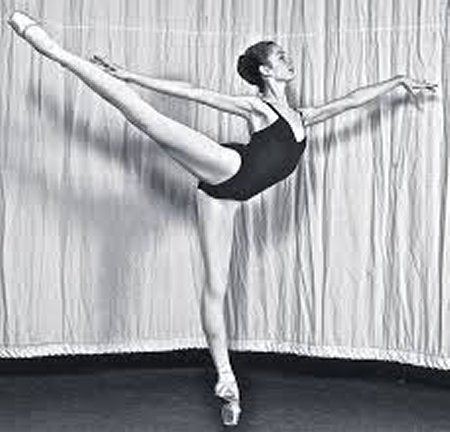

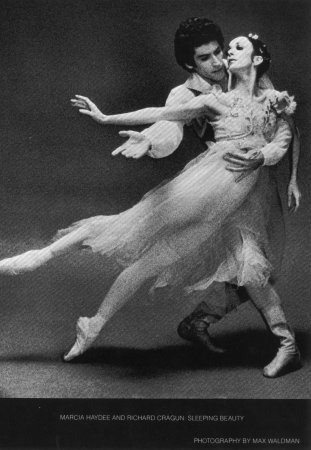

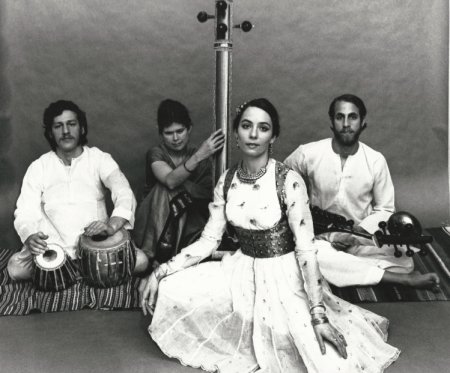

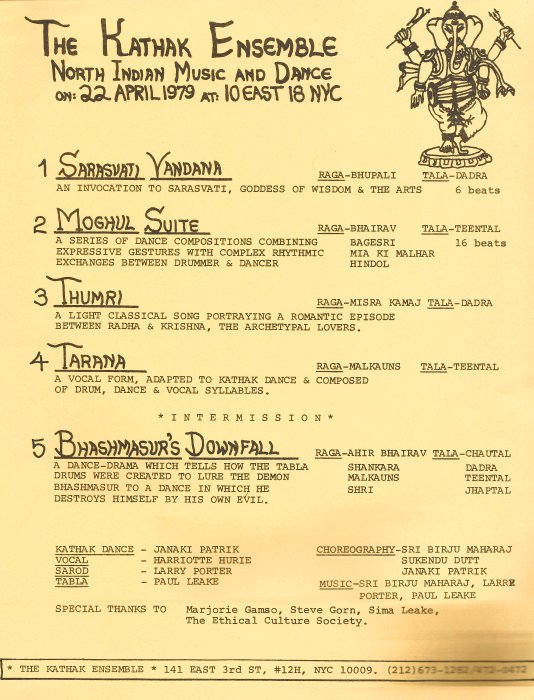

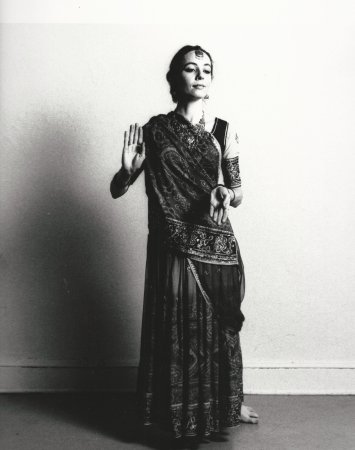

e-mail: janakipatrik@gmail.com New York City, Dance Capital of the World Photos courtesy: Janaki Patrik March 12, 2020 Moving to New York City in summer 1971, I enrolled at the Merce Cunningham Studio. A few weeks later the Studio held scholarship auditions. I was offered a work-study scholarship, and for the next seven years I took two Cunningham technique classes, six days a week. I also took a daily ballet class at another studio. Four and one-half hours total of training six days a week for seven years developed my stamina and kinesthetic memory. Merce's classes were never the same. We had a few warm-up combinations, such as 'The Exercise on Six' which began each class, but even those exercises could change. During one memorable summer, when Merce taught the Advanced class five days a week for six weeks, he changed the time cycle every few days. For whatever duration of days he decided to continue in that time cycle, Merce composed every warmup, every center and every across-the-floor combination in that chosen time cycle, whether 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11 .... Merce also taught a class in choreography. Two concepts which I remember him emphasizing were: 1. carefully construct the beginning and ending of your piece. The audience will remember those sections most clearly and judge your worth by them. 2. Don't show the preparation for changes of directions so transparently that they can be predicted even before you move. A prolific choreographer, Merce often premiered his new repertoire in New York City, whether in large venues like the 2100-seat Brooklyn Academy of Music, or in a museum or in his huge studio, where he presented what he called 'Events' for an audience of just 50 people. Attending every Cunningham performance and event he presented in New York City, I absorbed many lessons about choreography simply by watching attentively.  Summerspace, 1958  Event presented by The Cunningham Trust, 2017 Merce was influenced by his music director, the experimental composer John Cage, who was exploring concepts of "chance" in the Chinese 'Book of Changes' - the I CHING. Using throws of the dice, he determined elements in his compositions such as speed and progressions of notes. Applying "chance" to choreograph what he called "events", Merce threw dice to randomly select excerpts from several different productions, juxtaposing them in a single hour-long performance. The new configurations resulting from this process caused random "meetings" between sections of movement formerly framed in the fixed choreography of discrete productions. An emotional charge for dancers and audience alike resulted from the collision of unpredictable elements in "instant choreography". Every "event" demonstrated the electrifying result of "chance" - considered by some to be a dry, intellectual concept, but in Merce's hands, a potent generator of choreography. Some students in Merce's classes were inspired to create our own choreography in informal spaces in the city - abandoned factory lofts, after-hours school gymnasiums, and in one case, the deep hole in a vacant lot being excavated in preparation for construction. We chose dancers from among our classmates and experimented with concepts of chance, inversion, changes in tempo to alter movement phrases, and other compositional techniques used in new music. We danced in classes during the day, rehearsed at night and attended each other's performances. I performed in choreography by Marjorie Gamso, Daniel Press and others.  Janaki with Daniel Press in Gamso's piece A vast panorama of dance companies presents a broad spectrum of choreographic styles in New York City - some standard repertoire, some wildly experimental - which I attended night after night: traditional and experimental staging of operas at the Metropolitan Opera House, Phillip Glass' opera EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH, ballet standards presented by American Ballet Theater at City Center, Pina Bausch, Ballet Folkloriico de Mexico, Ballet Theatre of Harlem...  Suzanne Farrell Because I could frequently attend performances by George Balanchine's New York City Ballet Company, and because Mr. Balanchine presented an eclectic mixture of new music with classical and experimental choreography, I began to treat his programs like a textbook of choreography, and I have continued to see Balanchine's choreography whenever possible. His ballets and those of Jerome Robbins used the classical vocabulary to suggest emotion-filled relationships. Some of the accompanying music by composers like Stravinsky was chosen to upend expectations of classical beauty and symmetry. Dancers were chosen whose bodies could be trained to move at ultra-fast speeds, while flitting through distortions and extended body lines. The idea was partly to reflect the frenzy of modern life.  The Cage: Choreography Jerome Robbins, music Igor Stravinsky John Cranko, who choreographed for Germany's Stuttgart Ballet, presented his company several times at the Metropolitan Opera House. His story ballets depict emotional depths by using innovative concepts in ballet choreography. Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet and Taming of the Shrew, Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and Tchaikovsky's Sleeping Beauty all demonstrated ballet abhinaya that could be "read" by viewers in the last row of seats in cavernous western auditoriums. Dynamic musculature, grand gestures, and most strikingly in contrast with Indian choreography, partnering in which male and female dancers touched - these ballet techniques told stories as powerfully as minute facial expressions. Attending performances educated me in choreographic techniques.  John Cranko's 'Sleeping Beauty' - Marcia Haydee & Richard Cragan The Kathak Ensemble is born Rhythm was an essential element in Merce's teaching and choreography. Consequently his classes were always accompanied by a pianist, who was expected to hold a steady beat and play in any time cycle in which Merce composed an exercise. In 1977, I learned that one of the pianists, Larry Porter, had studied rubab in Kabul, Afghanistan with Ustad Mohammed Omar. When he moved to New York City, Larry played both rubab and sarod in Indian restaurants and was sometimes accompanied by the tabla player Paul Leake. Paul had just returned from Calcutta, where he had studied tabla with Ustad Keramattula Khan. We arranged to meet, had an instant rapport and immediately started to rehearse together. Larry Porter soon joined our rehearsals, playing naghma on the sarod. Our group was completed by vocalist Harriotte Hurie, who had been trained by Pandit Balwant Rai Bhatt and Dr. Premlata Sharma at Benaras Hindu University. Since we conceived of our group as a cooperative collective, we did not highlight any one of our names. We called our group The Kathak Ensemble, and we began to rehearse my Kathak repertoire in preparation for a performance.  The Kathak Ensemble founders - Leake, Hurie, Patrik, Porter (Photo: Daniel Entin)  Program notes - 22 April 1979  Saraswati Vandana (Photo: Grace Sutton) Bhashmashur's Downfall - The Ensemble's first major choreography Ustad Masit Khan, Keramatullah Khan Sahib's father, had told Paul a story about the origin of the tabla drums. According to this story, Shiva had thoughtlessly given the demon Bhashmashur a boon: anything he pointed at would burn up and turn into ashes. Pointing his finger indiscriminately, Bhashmashur began to terrorize even the gods and goddesses. To counteract this boon, Shiva devised a plan to intoxicate Bhashmashur with the beauty of Parvati's dancing. To accompany Parvati's dancing, Shiva split a coconut into two halves creating two drums. And it happened as Shiva had designed: Bhashmashur imitated all of Parvati's gestures and forgot what he was doing. At the climax of their duet, Parvati pointed to herself, Bhashmashur pointed to himself and burned up. Bhashmashur excerpt (copyright Kathak Ensemble) Based on this simple story line, I wrote a script. We all read, then re-read and revised the script. Then we assigned parts and read the script aloud and revised it further, until it seemed to flow naturally, like unrehearsed human speech. In this way the narration was shared by the musicians and I danced all the characters, as is customary in storytelling elements of Kathak. In this way, the Ensemble's first choreography established one of the core principles in its creations: that the audience could follow the stories in English, but through elements integrated into the performance itself, rather than pre-performance lectures. Larry was already an excellent accompanist for several New York City storytellers, supporting the mood of each characterization. He was also a very fine composer. Identifying the various characters in the Bhashmashur story, he composed signature phrases for the parade of gods and goddesses who came to Shiva's celebration. He also composed music for Parvati's dance, and for the jugalbandi between Parvati and Bhashmashur. Assuming that I would choreograph as easily as he composed, Larry gave me the music and told me to be prepared to show my choreography at our next rehearsal. Creating the choreography for all the characters and situations in BHASHMASHUR was a difficult challenge for me. To choreograph the parade of gods and goddesses was relatively easy. I have a large collection of art books with photographs of sculptures and paintings depicting gods and goddesses of India. I studied and imitated their iconic poses. And it was quite natural to use the elements of gat bhav to move the parade through space. But I did not know how to start the process of choreographing Parvati's dance and her jugalbandi with Bhashmashur. Larry grew impatient with my procrastination. He challenged me, saying that I had learned so many classical compositions, including jugalbandi between tabla and tatkar, that I should JUST DO IT. "Use the compositions you know as your model," he said in exasperation. Of course I did, and the solo dance drama BHASHMASHUR was born - and so was The Kathak Ensemble.  The frightened crowd told Shiva - whatever Bhashmashur points at bursts into flames and turns into ashes  Parvati listened. She felt Shiva's divine magic. She stood up and danced, and her dance became part of the heavenly music.  Bhashmashur  Parvati's dance  Trained in both classical Kathak dance (Pt. Birju Maharaj, beginning 1967) and Merce Cunningham modern dance technique (1971 to 1978), Janaki Patrik has choreographed thirty full-evening productions and numerous shorter works exploring an eclectic range of poetry, mythic storytelling and music. She is the Artistic Director and Founder (1978) of The Kathak Ensemble & Friends/CARAVAN, NYC. A dedicated teacher, Janaki has trained dancers to perform an extensive repertoire of classical Kathak, as well as her new choreography. Teaching and performing in inner-city schools through Urban Gateways/Chicago and Young Audiences/New York for forty years, Janaki has embodied the power of dance and music to communicate the interconnections of all cultures. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |