|   |

|   |

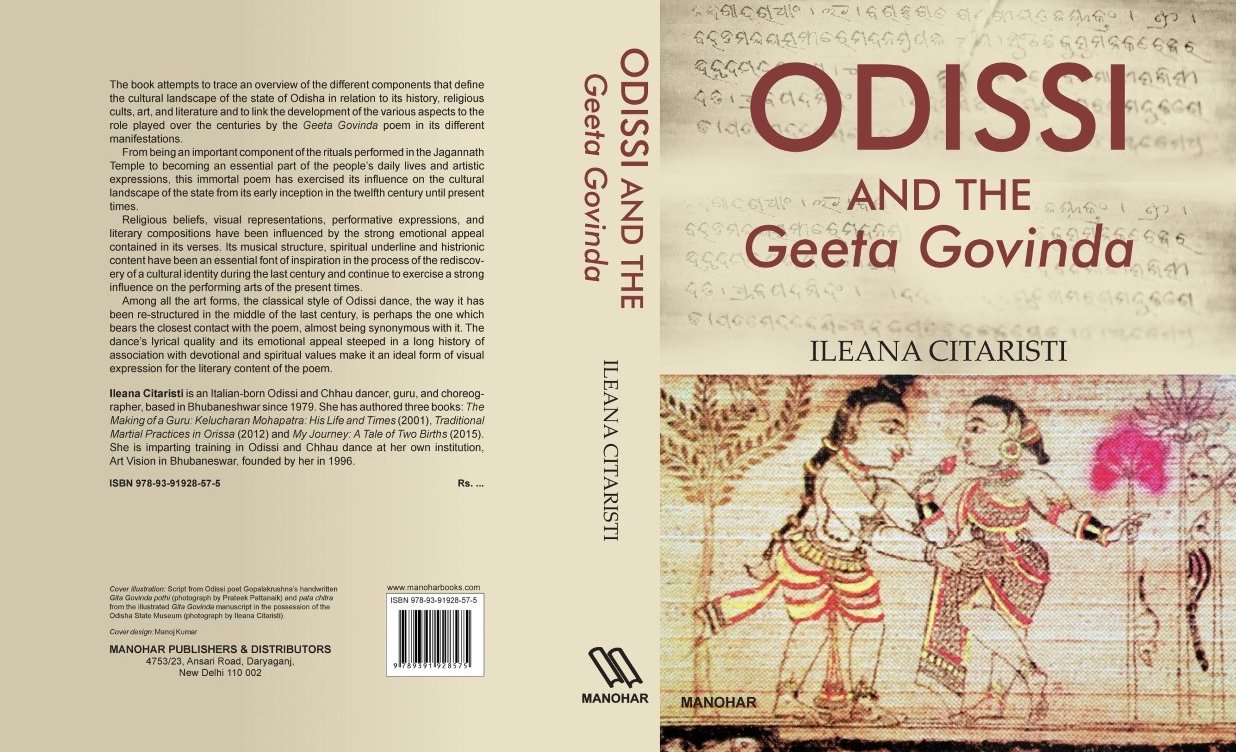

Tracing the roots of Odissi in the Geeta Govinda - Leela Venkataraman e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com April 27, 2022 Title: Odissi and the Geeta Govinda Author: Ileana Citaristi Publisher: Manohar Publishers & Distributors Year: 2022 Hardcover ISBN: 9789391928575 Price: Rs.1500 approx. An Odissi dancer and teacher of Italian descent, Ileana Citaristi, who made Odisha her home forty one years ago, has established credentials as an author, with her books Making of a Guru on Kelucharan Mohapatra (published in 2001), Traditional Martial Practices of Orissa (2012) and My journey-A tale of two births (2015). In her latest book Odissi and the Geeta Govinda brought out by Ajay Kumar Jain for Manohar Publishers and Distributors, she not only reiterates Odissi's special love for Jayadeva's prabandha, but also builds up a strong case for the Geeta Govinda having sown the very seeds of Odissi in the Orissan soil. A slender kavya by a son from Bilwamangal village in Odisha, Jayadeva's kavya Geeta Govinda almost colonised Indian art consciousness - with responses to it, in Odisha particularly, spearheading all disciplines - painting, sculpture, literature, theatre, music and dance. Odisha's Vaishnavite psyche woven round the Jagannath cult, and the temple at Puri housing the Lord with the Geeta Govinda as the sole text to be sung and performed while offering homage to him, underlines a unique association between temple and kavya. Expressed through multiple sources, with varying degrees of validity are innumerable myths, stories orally transmitted through the years, written chronicles, temple records like the Madalapanji and more factual information gleaned through historical writings, palm leaf manuscripts and inscriptions. What may be far from objective, like myths, can provide an insight into the working of the mind and attitudes of a people. That one needs to sift through a plethora of conflicting material before establishing plausible connections, points to the challenging nature of the task. And Ileana, in all fairness, does not spare herself any effort while wading through a host of material herself, and where necessary, supplements it with clarification from specialised texts. The result is a book, which in the reading, manages to establish almost a natural evolution, with efflorescence, from Geeta Govinda in text to Odissi as a classical dance.  The start of the book shows how fact and fiction are at constant loggerheads. The tale begins with the Satya Yuga myth in the Utkal khanda of the Skandapuranam, about saintly King Indradyumna hailing from the Surya dynasty, ruling over the Malaba Kingdom with Avanti as capital, who is told about the land of Nilachala, the Blue mountain, surrounded by trees and creepers, with a tank full of sacred water and with a wish fulfilling banyan tree on one side acting as an umbrella for the idol of Vishnu or Nilamadhava under it, made of sapphire bedecked with conch, wheel, mace and lotus in four hands of the deity. Shabara Deepak, a hermitage on the left, is surrounded by a hunter's (original worshippers of Nilamadhava) dwelling. On command, Vidyapathi, the King's messenger, after some hesitant help from the Shavara devotee, locates Nilamadhav, though by the time the King follows, the statue, enveloped by a violent thunder sandstorm becomes invisible. To cut a long story short, as ordained, after a thousand horse sacrifice (Yagna), the King is blessed with the appearance of a tree half buried in the sands, with the conch and wheel imprints on its trunk. And then comes the celestial voice, about the Lord fashioning his own image, with instructions regarding the colouring of the four fold wooden images - of Jagannath in cloud blue, Balabhadra in conch white, Subhadra in yellow and Sudarshan in red. The oracle also mentioned that the Shavara hunter be appointed as the main priest for prayers. For housing the images, Indradyumna assembling all the Kings, entrusted each with construction of one segment of the hundred cubits tall temple, after which, Brahma's consecration of the temple was accomplished with pomp on the eighth day of month of Baisakhi. Sarla Das' fifteenth century Odiya Mahabharata has another version pertaining to the Kali Yuga, when Indradyumna looking for the missing image to be put in the already constructed temple, is told about the half burnt body of Krishna, killed by the arrow of Jara, the father of Shabara Viswabasu, lying in the Rohini Kunda in a daru shape - which however, countless numbers of the King's men are unable to move. As told in a dream by Krishna, Jara and the Brahmin working together managed to lift the daru - and to this day both tribal and Panda are involved in the Jagannath worship in Puri. There are other variations of this myth - but with the inevitable refrain of the Shavara or tribal, as the original devotee of Jagannath and to this day, a fortnight before the Rath Jatra, the festival with the temple services are taken over by the Shavara tribe with the Brahmin purohits staying away. The temple chronicles (Madalapanji) dealing with the Jagannath temple are also a blend of legend and history. In the first half of the 10th century, they speak of Mahasivagupta Yayatakesari II who, after recovering the images lying buried for 150 years under a banyan tree locality (where the deities were hidden to save them from foreign devastation of whole of Puri by one Raktabahu) reinstalled them in the Badadeula. A chronicle on the Gangavamsi dynasty on the other hand mentions the deities being installed in Chudangasahi Madhupur Patana for laying the foundation of the Badadeula. As usually happens, various parts of the Puri temple are said to have been constructed under different rulers with the culmination under Anangabhima Deva II (1190 - 98). According to the Madalapanji it was Kavi Narasimha Deva (1278-1309) who initiated the practice of singing the Geeta Govinda in the temple. An Oriya engraving dated 1499 on the temple wall mentions Prataparudra Deva, a Gajapati ruler ordering the telinga sampradaya and the Oriya dancing girls to render verses from the Geeta Govinda only in front of Jagannath as well as Bada Thakur (Balabhadra). Several other kings connected with temple services are mentioned. It is also mentioned that during the time of Prataparudra Deva (1497-1540), the images were hidden to save them from destruction by the Mughals from Bengal who under Amir Sultan attacked Puri temple and destroyed other images. The iconoclastic destructions of Kalapahad during the reign of Mukunda Deva again led to the images being hidden in a pit at Prikud in the Chilika lake. Kalapahad discovered the hidden place but was killed even as he proceeded to burn the images. Finally during the time of Ramachandra Deva (1580-1609), appointed ruler of Khurda, the half burnt images were rebuilt and installed bestowing on the ruler the title of Abhinava Indradyumna. It is all a confusion of different versions and temple records too it must be remembered, are a mix of history and myth. It is pertinent that while historical records, both Ganga and Chola, agree on the Puri temple being built by Chodaganga Deva (1077-1142, the first king of Odisha's Gangavamsi dynasty born of the union of Rajaraja of the Ganga dynasty of Kalinganagara married to Rajasundari, daughter of the Chola King Rajendra Chola), this fact however is not stressed in the Madalapanji, which attributes the temple construction to Anangabhima Deva, who actually erected a Jagannath temple at Varanasi Katak (present day Cuttack). It was during the Suryavamsi dynasty after the Gangas, that the political heads became more closely connected with the temple's supreme deity. Puroshottama Deva (1467-'97) composed Abhinava Gitagovinda, with the idea of its recitation in the temple - but according to records, the deity, through signs, expressed his preference for Jayadeva's Geeta Govinda! Rai Ramanand wrote Jayadev Vallabha Nataka, another imitation of the amorous Radha/Krishna romance, which trained temple dancers of the time, performed in an amalgamation of dance, music and drama. That much like the south of India with devadasis serving the temple, Odisha had temples served by the Maharis is known. Madhukeswar (11th century) and Kurmeswar mandir (12th century) inscription mention Kalinganagar in which trained sanis (Telugu term for community of temple dancers) served in temples. Among others the book mentions yet another wrongly placed inscription in the Ananta Vasudeva temple (actually belonging to Megheswara Shiva temple constructed by son-in-law of Rajaraja II, Swapneswara Deva) testifies to dancing girls. In the 12th century Sobhaneswar temple, 6 miles from Kenduli, the birthplace of Jayadeva, dancing girls are mentioned. Chodaganga Deva who adopted Vaishnavism is said to have shifted to Varanasi Katak in 1126, the school which was in village Kurmapataka, for training sanis. Also mentioned is the inscription, now in the Royal Asiatic Society, is Kolavati (married to Haihaya dynasty general killed in a war) adept in music and dance. The chapter on the Mahari (described as derived from word Mahanari belonging to the swarga loka) has a lot of information, some of which is mentioned here, on the Bhitare Gahani /Gaoni, Bahare Gahani and the patuari (dancer in a procession). Not even the Bhitare Gahani, while accorded the exalted status of not having to salute even the King, was allowed to cross beyond the threshold leading to the inner enclosure or sanctum sanctorum of the God. After becoming the consort of the God and nityasumangali, through the saribandha ceremony, the girl/child's first entry into womanhood after puberty, comprised a night spent with the King (regarded as the deputy of the God). Sanctioned sexual relations were also with the high caste Pandas serving the temple. As in such practices in other regions, the Mahari system too, subjected to the highest of praise and condemnation was a curious mix of what one believes as the sacred and the lowly. The morning dance before the gaja stambha was just pure dance according to the Devadasi Nrutyakarika manuscript. Ileana mentions the tantric panchamakara, quoting from Sadashiva Sharma's book, describing the three poses adopted during the evening puja by the Mahari of makara karana (crocodile), hansi (goose) and kukkuti - as movements inducing the sexual fluid in females, signifying the union with the Lord. According to what Mahari Harapriya informed Ileana, this was abolished at the start of the 18th century. The symbols of sexuality associated with the Mahari are so strongly emphasized that even the main technical concerns of chauka and tribhangi are certified as symbols of fertility. The writer's explanation that acrobatic movements prescribed in the dance, as well as speed of turns must have been ways of evoking an absorbed rendition wherein the performer forgot herself, while perhaps correct, seems simplistic. The selection of temple dancer was not on merit, and many were from poor families taking oaths to send a daughter to serve the temple. By the mid fifties of the 20th century when a classical Odissi began to be crafted on the skeletal remains of whatever had survived the ordeals of history, whatever remained of the Mahari's involvement was very scanty and temple records mention four Maharis of the time - Kokila Prabha, Moni Prabha, Harapriya and Sashimoni. Much of what one recounts today is from whatever one manged to get as information from these existing Maharis of the fifties. Singing during the sakala dupa seemed to be the only part of the Mahari ritual still prominently in existence at that time. The bhoga part in the morning entailed only pure dance by the Mahari, with the bhava angle reserved for the ritual before the Lord retired for the night. The book has interesting details of the Mahari participation during Chandan Jatra, Rukmini Bibhaha Ekadasi, Snana Purnima, Rath Jatra, Nandotsava, Durgamadhav Puja and the rituals surrounding the Magha and Baishaka festivities, and the Rama Abhisekha and Dola Purnima celebrations. How the Akhadapilla and the Gotipua tradition started has been discussed. The argument that the increasing vandalism round religious institutions with hordes of invaders indulging in plunder and savagery making it difficult to guarantee the safety of Maharis in processions, paved the way for boys dressed as women, is one explanation. The other is the Vaishnav belief that the almighty being the lone Purush, the Madhura sringar bhakti entailed all devotees as female aspiring to become one with the supreme male - and hence the Gotipua. Technical details of the Mahari's dance with basic chali, minadandi, goithi chali, thia puchi, keda ghosara, pukhania chali are all briefly explained. Space being covered in circular patterns bhaunri as distinct from the bhramari movement now a part of the dance, is also explained. In a chapter devoted to some information about Jayadeva, mention is made of an inscription on the lintel 'jayajaya deva hare' of a 9th century Chandi temple at Kenduli (Jayadeva's birth place) - also called Padmavathi temple by locals. And all temples in the vicinity use the Madhava term so prominent in the Geeta Govinda - Prachi Madhava, Mudgala Madhava, Lalita Madhava etc.-pointing to the influence of Jayadeva. Apart from more than forty commentaries on the Geeta Govinda, one saw an upsurge of literary texts spurred by Jayadeva's poem. To mention some, in poetics there was Rena Kumbhar (1433-'63) of Mewar's Rasikapriya. On taal and musical system Haladhara Misra's Sangeeta Kalpalatika (17th century) on music of the Sanskrit cantos. There were more than a dozen Oriya translations, apart from Chandi Das' Bengali translation Srikrishnakirtan in the 15th century, Giridara Das' 17th century translation among others. Sri Sri Jagannath Ballabh Nataka by Raya Ramanand in the 15th century was followed by Banamali's Leelamrita in the same century, Rasamanjari by Devadurlabh Das in the 16th century, and in the same century Sishushankara's Ushabhilasa, Dina Krishna Das's Amrita Sagara in the 17th century and in the 18th century was Abhimanyu Samanta Sinhar's Bidagdhe Chintamani followed by Baladev Rathi Kishor Chandana Champu in the 19th century. Patachitra activity also abounded. A one act drama meant to be staged in the Jagannath temple during the annual festival, Piyush Lahiri, by Pindim Jayadeva was close to the Geeta Govinda theme. Even in the temple rituals during Ratha Jatra, enacting a peeved Lakshmi, with Jagannath's stay in the gundicha mandir during the Rath jatra, there is a great deal of built-in theatre with Pandas and Maharis representing the two sides. Indeed, contained in this byplay of Jagannath not being allowed to enter his home after the return jatra with one Panda deputising for Jagannath and another for Lakshmi, are the seeds of the many Rasleelas and Krishnalilas which became part of Odisha's theatre. The Jagannath Ballabh Nataka by Raya Ramananda which had music, dance and theatre, with several songs set in different ragas (which find mention in the Geeta Govinda ashtapadis), are expressions soothing the frustrations of Chaitanya in his separation from the Lord, showing the total surrender to the ecstasies of Madhura bhakti. Radha as abhisarika and the final union of Radha and Krishna are all part of the play. Chaitanya Charitamrtam even mentions Raya Ramananda choosing two young temple dancers and training them for the play. The gopis here were said to be trained to exercise self control wanting nothing for themselves, beyond satisfying the desires of Krishna. This play set in motion other works like Dana Keli Kaunmudi, a one act play by Raghunath Das, Vidagda Madhav by Rupa Goswami and Gopala Champu by Jiva Goswami and Krishna Das Kaviraj's Govindalilamrita. Any number of works after the 15th century followed including Kavi Surya Baladev Rath's Kishor Chandrananda Champu spread to many regions of the country - these works giving rise to forms of dramatic performances and even while there were regional differences of Assam totally eschewing the role of Radha, the works had the common denominations of Krishna, Gopis, sakhi in the typical Geeta Govinda format. In Odisha, Krishna's dalliance with Chandrabali took many forms. The Krishnaleela, Rasleela and Radhapremaleela were the precursors for a virile theatre movement which in Odisha, involved akhadapillas and other males trained in akhadas. Involved in and with the Rasleela troupes, were the great pioneers of the new classical Odissi movement during the second half of the 20th century like Guru Pankajcharan Das, Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra, Harihar Raut, Durlav Chandra Singh, Guru Mayadhar Raut and Guru Debaprasad Das. Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra was with the Mohan Sunderdev Goswami Rasleela group for years, playing, strangely, male roles mostly! The bhakti bhav in which these theatre presentations were soaked, acquired a more secular and performance oriented identity when theatre groups, like that of Kalicharan Patnaik, took to presenting Rasleela themes along with other fare, catering to mixed audiences. Thus in the first half of the last century, apart from Mohan Sundardev Goswami, other Rasleela troupes were directed by Govind Chandra Surdeo, Kalicharan Patnaik, Ranganath Dev Goswami and Bikari Charan Dalei. Kalicharan Patnaik, a known name in Odia literature and performing arts, started his own Rasleela troupe called Sakhi Gopal Natya Sangha in both Puri and Cuttack and on the staff were Mohan Mohapatra, a Gotipua dance teacher and Singhari Shyam Sunder Kar, the doyen of Odissi music and the Mahari style of dance. In the forties, Chhau in Mayurbhaj, Sakhi Nata or Dakhini Nata in southern Odisha were also prevalent. Debaprasad Das and Pankaj Charan Das as actors and dance masters were involved with New Theatre of Odisha. All these scattered groups got crystalized as Annapurna Theatres A and B at Puri and Cuttack. The details of how Pankajcharan as dance teacher, Kelucharan as percussionist (tablist at the time) came to be associated at about the same time with Annapurna B under Lingaraj Nanda (exposed to gotipua and Dakhini Nata), and how by introducing short dance items as curtain raisers before actual plays started, the process of dance in Odisha began enticing the best of talent, contrary to the notoriety the art had been burdened with so far, is a well known part of art history in Odisha. Pankajcharan's maiden composition Mohini Bhasmasura, stylistically not bound by later rules of classical Odissi, with Mohini dancing in 16 beats to Mahadev's dance of 10 beats, became a starting point for discovering Kelucharan's (in the role of Mahadev) aptitude for dance (he had never divulged his Rasleela experience) with Laxmipriya as the female partner - marking a red letter day in the Odissi journey. In 1946, for the play Sadhav Jhia (The Merchant's Daughter), for promoting sale of Patachitra and textiles in Bali, saw Durlav Chandra's choice of Dashavatar (based on Geeta Govind composition) as the perfect curtain raiser for the occasion, visualising through movement, a prolifically expressed motif in all Odishan art forms of canvas, murals and painting. Durlav Chandra's (had taken role of Jayadeva in the play in 1943, staged by Kalicharan's theatre group) music in raga Chandrakant set to 10 beats, with Pankajcharan's dance composition, created history - and the main frame of this work in raga, tala and dance has remained more or less the same to this day! One needs to remember that Durlav Chandra Singh brought to his work, influence from the Dhrupad style in which he was trained. Soon, arriving in the theatre scene was Dayal Sharan trained in the Uday Shankar mode at Almora. He came to Cuttack and joined Annapurna B. In Annapurna A, was Kartik Kumar Ghosh who had also had a six month training in the same school. With Mayadhar Raut, Sanjukta Panigrahi and Minati Misra entering Kalakshetra under Utkal Sangeet Natya Kala Parishad's scholarship, a nucleus of persons trained in Sastra and Prayog (even if the dance form was Bharatanatyam, including Kathakali in case of Mayadhar) came into existence, exposed to a systematised method of dance learning. Simultaneously there was Singhari Shyam Sunder Kar, who taught Priyambada Mohanty for the annual Utkal Sangeet Samaj performance. In 1948, the performing arts scene of Odisha, acquired its finest support in the form of the new Director of A.I.R at Cuttack - P.V. Krishnamurti, who was to play a very big role in promoting music and dance in Odisha. The state sponsored Kumar Utsav at Cuttack from 1952 provided a fine platform for the promotion of arts. The active scene threw up a crop of talented musicians and playwrights -Balakrushna Das, Bhubaneswar Misra, Hariprasad Chaurasia, Nilamadhav Bose, Suren Mohanty, Kalicharan Patnaik, Nayan Kishor Mohanty and Ananda Charan Das. Soon the dance teachers previously connected with theatre, got employed by dance and music training institutions and dance dramas like Kishor Kanha (1953), Urvashi (1954), Sakhi Gopal ('54 jointly choreographed by Kelucharan and Pankajcharan staged for the Industrial Trade Fair in Delhi), Rasleela (55),Konark Jagarana (1958), Nandan Nupura ('57), Jeevan Darshana ('57) and several others followed in the post fifties. With both Kelucharan Mohapatra and Mayadhar Raut working for the Kala Vikash Kendra, inevitably competition led to some misunderstandings. Despite what went as Odissi being staged for the International Youth Festival in Delhi in 1954, where Priyambada won a prize along with warm words of praise in the Statesman from Charles Fabri, it was after the Jayantika meetings held following the first meeting of concerned persons called by Dayanidhi Das in 1958, that hallmarks of a classical Odissi style with a performance format, were worked out - despite strong differences of opinion. In September 1959 at Nari Sangha Sadan, Cuttack, the five segments of a concert with Mangalacharan, Batu, Pallavi, Abhinaya and Moksha were presented - with demonstration of technique with Bata Krishna presenting charis, Dev Prasanna Das demonstrating uptlavanas, Dhirendra Patnaik presenting bhangi and karana and Mayadhar Raut demonstrating hand gestures. The musical team comprised Balakrushna Das and Raghunath Panigrahi and Binapani Misra providing vocal support, Guru Kelucharan providing mardal support, and Sunakar Sahu on the violin. So far, the gurus while adopting a prescribed technique composed items, built on strong individual predilections - like Pankajcharan who had his Mahari dance preference, Debaprasad whose belief lay in the folk forms as containing the special Odisha identity, Mayadhar Raut whose training in Kalakshetra laid stress on the theoretical aspects and Kelucharan whose prolific creativity based on a painterly mind drew its inspiration from revisiting temple sculpture, patachitra and observing life all round studying postural patterns of behaviour, particularly in women. Both Pankajcharan and Debaprasad were drawn more to Oriya compositions. The Geeta Govinda poetry for a long time did not go beyond the lone Dashavatar ashtapadi. Whatever ancient rulers had ordered for the Maharis got lost in the upheavals of history in this region. In 1958, "Lalita lavangalata" was presented in the All India Dance Seminar by Sanjukta, with Kalicharan reading a paper. "Yami he kamiha sharanam" and "Pashyati dishi dishi" were presented by Priyambada Mohanty at Sapru House for an LTG event. In 1966, Kelucharan's elaborations woven round Radha looking for Krishna in "Pashyati dishi dishi" in many venues, raised elaborations spun round a statement to unforeseen levels. The ashtapadi was also composed for Kumkum Mohanty by Mayadhar Raut and the same dancer also performed "Chandana charchita" with music by Balakrushna Das in Ramkheri raga.With personalities like Rukmini Devi who frowned on erotic literature as material for expression through dance, taking up some of the ashtapadis in the Geeta Govind, at that time, was not easy. But even Rukmini Devi was won over by Kelucharan's visualisation of "Kuru yadu nandana." The mention of how Kelucharan would take more grown up dancers like Ileana aside to explain lines which younger students were not allowed to question, makes interesting reading. It is after reading this book that I am able to understand Kelucharan's inclusion of the non-Jayadeva lines pertaining to Krishna's lame explanations for Radha's accusation pointing to the telltale marks of dalliance with another woman on his person in the Ashtapadi "Yahi Madhava yahi Keshava" ashtapadi. This came directly from the revised Manobhanjana, inspired from Guruji's Rasleela days - when Lalita points out all the marks on the person of Krishna and he tries to provide utterly unconvincing explanations as answers. The strong Rasleela influence had led to insertions as explanation between Jayadeva's text (making Krishna look like an erring school boy). The details with the year of each ashtapadi being composed for a student are all detailed in the book and these facts were printed in an excellent brochure brought out on Guru Kelucharan's 80th birthday celebrations. Jayadeva's kavya, which specifies ragas for the ashtapadis, played a part in fashioning Orissan music. From the grama murchana system existing at the time of Jayadeva, to the prevailing Melakartha system, music has undergone changes - making it well nigh impossible to recapture the ragas with the same value in notes as specified by Jayadeva. From the 13th century came the amalgamation of influences brought by the Persian and central Asian invaders to India. The book mentions how amidst all these changes raga Vasanta for "Lalita lavangalata" has remained, though the raga as rendered then and today,would be different.The early Pallavi composed by Balakrushna Das in the early fifties in this raga, also has words describing the dhyana murti of the raga, comprising a form meditated upon, reflecting the qualities characterising a raga. Odisha's music which showed similarities with the Carnatic ragas is now developing showing a greater affinity with the Hindustani system of ragas. Dasavatar which is prescribed to be sung in Malawa raga which Sangita Damodara describes as the King of ragas, also has the dhyana shloka - visualising a lotus faced hero kissed by a beautiful woman. The same raga is prescribed for the ashtapadi "Yami he kamiha sharanam." "Yahi Madhava" has always been in Bhairavi, and Ileana mentions the differences in the raga from the morchana to the prachalit form. Not ending with the reference to musical nuances, the book goes on to the Prabandha poetic form in which Geeta Govinda has been composed. According to Geeta Prakash, prabandha is suddhageeta with three major components -the initial part (udgraha), the middle parts (dhruva), and the concluding part bearing the author's name (abhoga).As pointed out by Ileana, in a poetic work full of all types of metrical patterns, sound patterns, alliterations, assonances, consonances and endings with rhymed lines, any composed music will have to take note of all these points, which together constitute the inner rhythm of the song - while not forgetting the mood that the ashtapadi evokes. And it is here that a composer like Bhubaneswar Misra proved his worth. While ashtapadis were set to dance by all Odissi gurus, it was Kelucharan Mohapatra who came to be known as the Odissi King of the Geeta Govinda. From the Kavya to Odissi as practised today, the story is of the working of the mind and art trends set in motion by Jayadeva's work - trends which with the transitions through time have resulted in classical Odissi. Ileana manages to catch echoes of this movement through time, in her latest work. Whether it is Odissi and the Geeta Govind, or the Geeta Govind and Odissi, it is worth a read for all interested in Odissi history. P.S. In this article, I have stuck to the spellings given in the book, like for instance Geeta Govinda, which is usually spelt Gita Govind. Similarly some proper names from history which never seem to have a set spelling. For example, what I have always read as Balakrushna Das, is here spelt Balakrishna Das and also as Balakrushna Das.  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Post your comment Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous / blog profile to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted in the blog will also be featured in the site. |