|   |

|   |

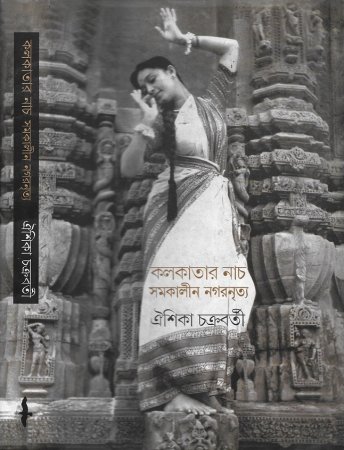

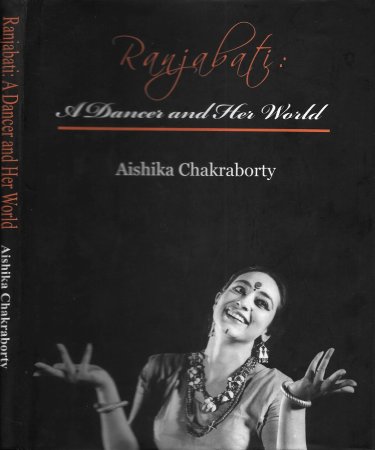

Evolution and mutation of dance in Eastern metropolis - Dr. Utpal K Banerjee e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com November 4, 2020 Kolkatar Naach, Samakaleen Nagarnritya Aishika Chakraborty 2019, Rs. 450 ISBN 978-93-86443-80-9 Gangchil.books@gmail.com Ranjabati: A Dancer and Her World Edited & Introduced by Aishika Chakraborty Thema 40 Satish Mukherjee Road, Kolkata 700 020 2018 (third reprint), Rs.500 ISBN 978-93-81703-67-0 The three villages, Kalikat, Sutanuti and Govindapur -- where Calcutta was located -- came into the possession of the British East India Company only in 1690. Some scholars like to date the city's beginning from the construction of Fort William by the British in 1698, though this is debated. From 1772 to 1911, Calcutta was the glorious capital of British India. This status was lost when the capital was shifted in 1912 to Delhi. But up to India's Independence in 1947, it remained the capital of the entire Bengal. Only after Independence, Calcutta (now Kolkata) became the capital of the truncated Indian state of West Bengal.  Reviewing two of the most significant books penned by an erudite professor - the first on the city's own dance history (in Bengali) and the second on one of its most promising products who died tragically too early in life (in English) -- the brief history of the city itself is worth keeping in the background. This is just to remind one that Kolkata had no haloed existence since antiquity, unlike Delhi or London or St. Petersburg. Indeed, Kolkata could easily be marked out as quite an "upstart" city with no in-built culture of its own, which literally came from the immigrant skilled labor bringing in their own village traditions alongside their rites and festivities. There also grew "White Town" mainly on the banks of the Ganga with the colonizing masters and the rest of three-fourth township made into "Black Town" with the hoi polloi. Soon, in the middle of this divide emerged a middle class - educated and enlightened, faithful to colonizers and remarkably class-conscious. These "Brown Sahibs" contributed substantially to the genesis of an urban culture - out of, but distinct from, the rural traditions prevalent on ground. An inevitable community of dancing females for entertainment and enjoyment drifted in - socially deprecated, yet often highly cultivated and proficient in the performing arts - flourishing in the 18th but dwindling in the 19th century and virtually vanishing thereafter. But for the reality of Kolkata having ultra-strong colonial moorings, one should have paid more attention to the hinterland it is situated in. The undivided Bengal - linguistically defined, not politically, the latter boundaries changing with different political regimes - has been well known in Indian history for its rich cultural proclivities, which were bound to seep in into the fast growing metropolitan area. For Bengal, hugely respected for its love for all genres of music from classical to folk and tribal, it is remarkable that the region was virtually untouched by the classical and temple dances, despite the same surging around the region over the ages. Vestiges of Kathak that spread all over North India - from its fount head of Vrindavan - carried by the disciples of Haridas Swamy (guru of Tansen and Baiju Bawara) to Delhi, Gwalior (Raja Mansingh Tomar), Aurangabad (Gopal Naik), Darbhanga et al, proliferated alongside the music of Dhrupad in the 15th century, reaching Vishnupur by the 18th century but not spreading beyond. Shri Chaitanya's own obsession for the Radha form of dance - with its devotional fervor in the 16th century - did not seem to leave much of its mark beyond Nabadwip into the southern deltoid region of the Ganga. On the other hand, his influence traveled East and Northeast. Saint Sankaradeva (and his disciple Madhavadeva) created Sattriya dance, along with Ankiya Nat (sans Radha) that was preserved in the holy Sattras of Assam. Manipur had already its highly ritual Lai Haraoba in the pre-Vaishnava era and embraced Ras Leela and Nata Sankeertan under Vaishnava influence. When Shri Chattanya visited Odisha (where he spent the rest of his life), the dancing female Maharis and the male Gotipuas in and around Jagannath temple in Puri enthusiastically adopted Geeta Govinda under Chaitanya's abiding influence, but the upsurge in temple dance did not ripple back to the Gangetic shores of Bengal. To set the records straight, Bengal's "very own" Gaudiya Nritya is recently being reconstructed based on archaeological and scriptural evidence, but it needs strong collaboration dancers, archaeological scholars and socio-cultural experts, to be indisputably adopted as a heritage dance of Bengal. While all of the above is yet to be studied in depth, the present author has done a valuable job in documenting what remained inevitably to happen, namely, the Western dance movements sending ripples back vigorously to Kolkata, its colonial vanguard in the East. The three personalities spearheading this upsurge were Rabindranath Tagore, Uday Shankar and Manjushri Chaki-Sircar (and her daughter Ranjabati). All three have been examined in the first book in great detail and deserve appreciation. Tagore's adolescent exposure to London's society dances, namely, three vigorous dance forms: Galop, Lancer and Mazur (but not the more popular, but slow, Waltz) perhaps helped to create stirrings of dance within him, but not much later, until the early decades of the 20th century, did he get an opportunity to introduce dance, as part of curriculum, amidst the children at the emerging Ashram school in Santiniketan. He had a chance to see Manipuri dance in Tripura in the 20's, which encouraged him eventually to use Manipuri, for the first time, for a conservative family girl on public stage in the role of the Buddhist Nati in his play Natir Puja in the late 20's. His exposure to Kerala's Kathakali, Sri Lanka's Kandyan dance and Indonesia's classical dances, amongst others, are very well documented, which made him enthusiastic to compose several sterling dance-dramas in the sunset decade of his life. His system to use abhinaya for solos and folk rhythms for group dances focused on mood-dance of his rich "sahitya" on the whole, was honed considerably by the methodology brought in by his daughter-in-law Pratima Devi from Dartington Hall, UK. Uday Shankar, a luminary in dance creation and presentation in India, was from Rajasthan born to a Bengali family and came to settle in Kolkata only in his last few years. His arts education in London and joining the great ballerina Anna Pavlova, his partnering her in the UK, followed by a highly successful American tour, and Anna's dissuading him from joining her own troupe in order to return to his own country are facts well-recorded in history. After innumerable successful world trips with his own group, the brilliant artist created his own dance training center at Almorah, UP, and went forward to create the immortal dance movie Kalpana, shadow plays and a mixed media wizardry Shankarscope, the last one never fully analyzed. Indeed, his own highly innovative training method also remains undocumented and the two major dance schools in Kolkata by his scions follow his style mainly in spirit, but hardly in letter. The best part of the first book is recording and analyzing Manjushri Chaki-Sircar's work, leading to her formulating Navanritya style. Again, Manjushri spent, with her husband, a major part of her life in Africa and, later, many more years of learning and performing in the USA. Her doctoral work was on Lai Haraoba in Manipur. Returning to India, setting up 'Dancers Guild' and creating highly innovative dance choreographies have been well delineated here that can be considered Kolkata's true dance legacy, granting that Tagore's oeuvre was all created out of Santiniketan and used mostly to be showcased in the city of his birth and growth.  The second book is really a compendium of Ranjabati's assorted writing, along with a lucid, painstakingly written introduction on the brilliant young dancer, analyzing her random thoughts on dance and all the related aspects she could think of. Given some more time, this could have led to a coherent 'worldview' culled out of an enormously varied exposure and experience of a Western choreography work and synthesizing the same with her rock solid grooming in the Indian classical repertoire. To illustrate the latter one can quote, first, the author's astute observations, "She grasped different dance forms and still felt it necessary to articulate an original grammar, different from its classical counterpart. Of the varied physical influences, Ranjabati heavily drew on the poise and power of Kathakali. The dance that uses the lower back as the pivotal point and liberates the face from prettiness, laid the foundation of her technique. The use of the diaphragm in Bharatanatyam in creating linear energy, speed, its outwardness and crispness was the second inspiration that shaped her methodology. Ranjabati took lessons in sattvika abhinaya from Kalanidhi Narayan to use the face and the body as subtle instruments of expression… Ranjabati's own thrust, however, was to de-construct the abhinaya technique and use it differently in Navanritya. A gentle influence came from Manipuri, which dwelt on flow, inwardness and subtlety. Ranjabati also imbibed the strength manifest in Yoga and the freedom of Chhau and Thang Ta, the martial arts of Eastern India…. (Also) she was exposed to Kalaripayattu that stimulated her to think afresh about the body and its movements." (pp 15-16) The above lengthy quotation would go to show how she was led - in addition to the potential of improvisation - "to develop ideas about centre, energy, line and space that had been a part of her vocabulary." Add to that the seminal influences: Martha Graham's breathing rhythms of 'contraction and release'; Doris Humphrey's method of 'fall and recovery'; the uninhibited physicality of African and black dancers; the loose but controlled steps of Beijing Opera; and the martial art prevalent in Japan; and one would guess, from the vast choreographic oeuvre that she created within her criminally short life, and how she was on the verge of evolving a 'worldview' of Indian dance, even beyond the well defined methodology that she had already helped to espouse for Navanritya! The only aspects missing from the second book are the valuable interactions Ranjabati would have had with the Western and other choreographers she worked with. As regards her personal relationships with the other gender - including the man from Santiniketan whom she briefly married and separated from - there is golden silence. Even allowing for a wholesome regard for privacy, this is a huge loss for the reader: in being unable to appreciate the complete persona of one who, after a meteoric existence of only thirty-six springs, would no more be there with us.  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comment Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous / blog profile to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted in the blog will also be featured in the site. |