|   |

|   |

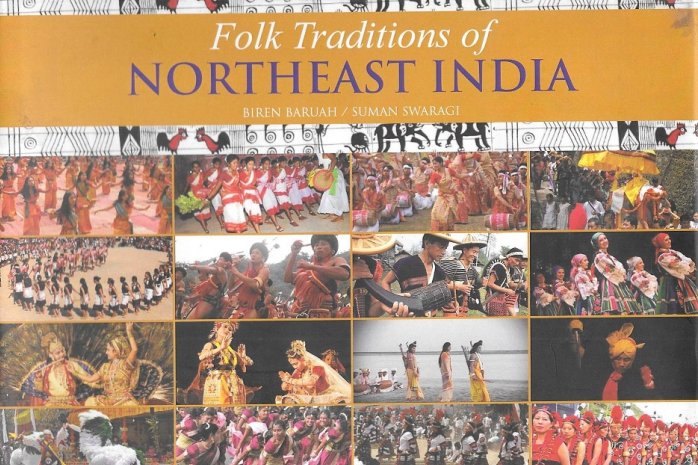

- Dr. Utpal K Banerjee e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com January 12, 2020 Folk Traditions of Northeast India By Biren Baruah and Suman Swaragi Shubhi Publications 479, Sector 14, Gurugram-122 001, Haryana e-mail: shubhipublications@yahoo.co.in ISBN: 9788182903074 Price Rs. 1495 "The Seven Sisters" of the North-East India (comprising Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Meghalaya, Tripura, Mizoram and the large state of Assam), plus the native kingdom of Sikkim added in 1975- with their low-lying Khasi, Jaintia, Lushai, Garo and Naga Hills, and the sprawling Barrack and Brahmaputra Valleys - offer an undulating physical topography. This beauteous landscape offers a human settlement that dates back to the Austro-Asiatic languages, followed by Tibeto-Burmese population and then the Indo-Aryan speakers from the Gangetic plains, half a millennium before Christ. The overall anthropological mix has resulted in an amazingly rich ethnic and cultural outcrop, not easily matched by any other part of our land. Scores of tribes in this sub-Himalayan region - dotted with picturesque hill-top hamlets of Nagaland, for instance, only matched by a highly evolved pre-Vaishnava culture of Manipur -- offer a fascinating mix of performing and visual arts, and handicrafts that boast of a bewildering variety of creative human imagination. The present book takes the reader through this culture-scape, if you like, with a hand-held tour of their dance and musical heritage. To this critic, the common features would seem that while their vocalized melodies are usually of a lilting tenor, sung in medium to slow tempi, almost capable of echoing from one hill to another, most folk dances have soft, undulating features of torso, and gentle footsteps that bespeak of an unhurried lifestyle of yore. In common with the human civilization of hunter-gatherers that evolved a few thousand years ago, their characteristic habitat with communes, consisting of a few scores to some hundred members, and their worship of pantheistic deities using simple rituals, crystallized into a folk culture of singing and dancing around those small-time deities and associated ritualistic practices. The book leaves a potential of common ethno-cultural inferences to be derived from the rich material garnered here and a fond hope that this would be taken forward in future editions. Otherwise, there is indeed a rich survey of the North-eastern culture-scape, treating the region as the melting point of different cultures and traditions. It is the home of more than 160 different tribes, each speaking a different language, with each tribe celebrating its unique and colourful festivals, reflecting their modes of living and livelihood. A kaleidoscopic overview is offered below.  Assam occupies the lush lowlands of the spread-out riverbank of mighty Brahmaputra, with Majuli, the largest inhabited riverine island, as the focal point of Vaishnava culture and well-known for its Satras (monasteries). It is also the home of Sankaradeva, the most honored saint of the 16th century. Assam's culture is interwoven with the Satras and Namghar (prayer hall). Besides a number of ritualistic dances performed by several tribes of the state, there are many dances that are woven to everyday life and also recreational in nature. Bihu is a major genre of dance here, having its roots in some earlier fertility cult that is reflected in various songs, expressions and movements, depicting joys of youth. Rangali Bihu is associated with Bohag Bihu, celebrated in spring (usually mid-April) to mark New Year. Bhogali Bihu is linked to Magha Bihu (harvest time), meaning feast and pleasure. Kangali Bihu, connected to Kari Bihu, signifies a store-house empty of food grains and with preparations afoot for the next harvest. Beguramba Bihu is performed by girls of Bodo tribe, to mark the mid-April cow worship, with flutes and split bamboo pipes. Mishing Bihu is performed by Mishmi tribe, marking cultivation from sowing to reaping. Oja Pali dances are part of local cults, with the Oja as chief dancer and bearing evidence of Indian classical dances, by showing elements of 'Hasta', 'Gati', 'Bhramari', 'Utplavana' and 'Asana'. Deodhani Nritya in south-west Kamrup area is a ritual dance associated with snake goddess Manasa. Behula is another ritual dance enacting the popular Behula legend. Jumur Nach is performed in tea gardens. Bhortal Nritya is an invocatory dance for the classical Satriya dance, performed with bhortal (large cymbals). Bodo Kherai and Rabha dances are performed by the respective Bodo and Rabha tribes. There are still tribal dances galore! Arunachal Pradesh ("Land of the Rising Sun") has dance as an integral part of its community life, forming a vital element of the zest and joy of living of the tribal people. Losar, Mopin and Solung are major tribal festivals. The indigenous communities dance on important rituals, during religious festivals and also for sheer recreational occasions. Varying from the highly stylized dance dramas of the Buddhists to the virile martial steps and colourful performances of the Noctes and Wanchus, Arunachal's dances are predominantly group compositions, where both men and women take part. Women are, however, debarred from Igu dance of Mishmi priests; war dances of the Adis, Noctes and Wanchos; and ritual dances of the Buddhist tribes. There are still Aji Lamu, Lion, Deer and Peacock dances by the Monpa tribe, Ka-Kong Ton-Kal dance of the Monpa tribe, Nongrong dance by the Tsanga tribe, and many others. Manipur ("Land of Gems"), the home of the Meiti people, has breathtaking blue hills overlooking the sprawling Manipur river valley. The land is reputed for its tradition of arts. Thang Ta, the state's martial arts, is recognized for its almost poetic renditions. Lai Haraoba (literally "Merrymaking of the Gods") is an age-old festival displaying beliefs of the people through rituals, dances and songs, usually held over 10 to 15 days at every locality of Manipur. There are a number of jagoi (dance) movements of men and women, called Thougal Jagoi. In particular, the priestesses, Maibis, execute a number of dances under Maibi Jagoi. With the influx of Chaitanya's Vaishnavism, Manipur developed new community dances, Raas Lila and Nata Sankeertan. Both these dances have highly dignified movement repertoire, rich rhythms, and themes and emotions deeply rooted in the scriptures. Cholam dances are popular masculine dances and are performed by men alone with musical instruments, such as, Pung Cholam, Kartal Cholam, Duff Cholam and Khol Cholam. Meghalaya ("Abode of the Clouds") is exceptionally rich in tribal culture and folklore. While Nongkrem and Shad Sukmynsiem festivals of the Khasis, Beh Deinkhlam of the Jaintias and the harvest festival of the Garos are replete with dancing and drinking, to the accompaniment of music from buffalo horn singas, bamboo flutes and sonorous drums. Khasis have a special spring festival dance called Nongkrem. Wangala dance is a most important part of the post-harvest festival of the Garos. Mizoram (the name derived from the local term for "highlanders") comprises the Kuki, Pawi, Lakher and Chakmas, many of whom were formerly head-hunters. One of the finest choir singers, Mizos have music and dance as important elements of their cultural life. Their important dances - celebrating life in all its richness - are the Chu Lam, Cheraw, Solakia, Sarlamkal, Khullam, Chawng-laizawn, Thanglam and agriculturally-inspired festivals of Chapchar Kut, Mim Kut and Pawl Kut. Nagaland (derived from the Sanskrit word "naga" for mountain) has more than 20 tribes and as many sub-tribes, with over 60 spoken dialects. Costumes are distinctive for each tribe in terms of design and colour. An important feature of all Naga dances is the comparatively little use of the torso and shoulders, and no circular movement of the arm too. Accompanying the erect body, there is a great deal of flat feet in hops, jumps, skips and leaps. Akok-khi is one of the most solemn dances among the Sangtam tribe. Kimbku dance is performed by the Chang tribe forming a hand-held circle and a slow tempo picking up gradually a frenzied pace. Dance of the Zeliangs have rows of men and women forming an inverted T-position. Wadir Naga Dance is regarded as a highly respected dance among the Aao tribe, while Zemi Dance is performed at night with torches. Sikkim ("New Place") is surrounded by precipitous mountains, dominated by the mighty Kanchenjunga. While three-quarters of Sikkim is Nepalese in origin, mostly Hindus and speaking Nepali or Gorkhali dialects -- the Bhutias, Lepchas and Limbus are significant minorities who speak Tibeto-Burman dialects and practice Mahayana form of Buddhism. The most popular dance forms are the Chams, ritual dances of the Lamas featuring colourful masks and quaint musical instruments. The festivals include Losoong (for Sikkimese New Year) in January-February with Guthar Cham, Tshiding Bhumchu in February-March, Saga Dawa, the holiest Buddhist festival celebrating his birth, Drukpa Tseshi celebrating his preaching of the Four Truths, and Phanglahabsol in August-September in which masked dancers honor Kanchenjunga. Lastly, Tripura, an erstwhile princely state with stunning natural beauty, has 19 tribes. Of these, the Tripuris are the largest while the Reang tribe from Chittagong (Bangladesh), is the second largest. Being largely rural, tribal customs, folklore and folk songs dominate Tripura's culture. Two major annual ceremonies are Garia (in April) and Kas (in June-July), involving merriments around animal sacrifice. Jhum cultivation forms the focal point for music and dance. Other popular dances are Maimata of the Kalol communit, Hoi Hug dance performed by Marsum tribe, and Hoza Giri dance of the Reang community. The book has also a useful section on folk music of Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh. One can perhaps look for more coverage of music of other regions, particularly of Assam which has a rich melodic heritage. All in all, it is a very useful treatise of its kind, lovingly produced by Shubhi Publications with no pains spared to lavishly illustrate the dance forms in full colour. It is a work to cherish!  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comment Unless you wish to remain anonymous, please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted in the blog will also be featured in the site. |