|   |

|   |

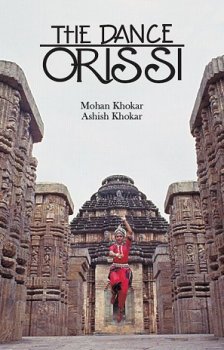

Down Memory Lane - Dr Sunil Kothari e-mail: sunilkothari1933@gmail.com November 23, 2011  The Dance Orissi by Mohan Khokar (and) Ashish Khokar The Dance Orissi by Mohan Khokar (and) Ashish KhokarAbhinav Publications, New Delhi / First Edition 2011 / Price Rs 3,360 Pages 340 colour illustrations 163 black and white 258 / Size 30x 22 cm. At the very outset, I would like to congratulate Ashish Khokar, for taking pains for more than 10 years to bring out the last book of his late father Prof Mohan Khokar on Odissi dance. He has done a commendable job as best as he could. For me, this book is like ‘down memory lane’ because Mohan Khokar was my friend, philosopher, guide and a mentor. It brought several memories alive for me. I had attended All India Dance Seminar and festival convened by Sangeet Natak Akademi at Vigyan Bhavan in April 1958. We, including a galaxy of dancers, scholars, authors and critics, had seen for the first time demonstration of Odissi by late Guru Deba Prasad Das and one dancer Jayanti Ghosh from Cuttack when late Kalicharan Patnaik, the renowned scholar, poet, dramatist, actor, and director, read a paper on Odissi. Mohan-ji and I had met Babulal Doshi, a Gujarati social worker during the seminar. He had established Kala Vikash Kendra at Cuttack to train young children in Odissi by engaging teachers like Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra and Guru Mayadhar Raut. Young Kumkum Mohanty (nee Das) was one of the gifted young dancers who later on became famous along with Sanjukta Panigrahi (nee Mishra) and Minati Mishra (nee Das). Babulal Doshi invited Mohan-ji and me to conduct further research in Odissi. Mohan-ji was then editing for Dr. Mulk Raj Anand, a series of special issues of Marg on classical dance forms like Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Kathakali, Manipuri. In that series, Mohan-ji edited one special issue on Odissi in March 1960, after visiting Orissa. On page 188, a photo in the page of Marg special issue of Odissi (vol XIII March 1960 number 2), gives a list of contributors also, major of them are Oriya scholars. These are primary resources for any student /scholar/writer on Odissi dance. During those years, under guidance of Mohan-ji, I also undertook researches in dance forms including Odissi and visited Orissa regularly for more than 15 years taking photographs, interviewing gurus, dancers, scholars and watching performances of Odissi. Dr. Mulk Raj Anand and Marg Publications published my book on Odissi, with photographs by Avinash Pasricha, in 1990. Therefore browsing through the book, so many memories came alive. Ashish has mentioned in the end on page 331 under the heading Bibliography: ‘As this is the first definitive book on Odissi, the list is short.’ At the end there is a note: For detailed listing consult: www.dancearchivesofindia.com OR www.attendance-india.com Index, glossary, acknowledgements for photo credits and bibliography are prepared once the final text is submitted. This is the normal practice. This should have been done say by 2009, if we take into account the final year of publication to be 2010. Many books have been published between 1990 and 2010. To give a few examples. Besides my book Odissi: Indian Classical Dance Art by Marg Publications in 1990, the 2nd edition of the first major book on Odissi in English Odissi Dance (1990) by Dhirendra Nath Patnaik; Abhinaya Chandrika and Odissi Dance (2001), as the first attempt to annotate and translate from Sanskrit manuscript of Abhinaya Chandrika of Maheswara Mahapatra in English by Maya Das; book of Dr Priyambada Mohanty-Hejmadi and Ahalya Hejmadi, Odissi : A Classical Dance of India (2006), , Odissi exponent Ranjana Gauhar’s book Odissi, the Dance Divine (2007); a series of books on classical dance forms edited by Alka Raghuvamshi for Wisdom Tree , Odissi by Sharon Lowen (2004); Italian Odissi dancer, Ileana Citaristi’s biography of Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra, The Making of a Guru: Kelucharan Mahapatra: His Life and Times (2001 and 2004); another major book, with ‘no holds barred approach’ Re-thinking Odissi by Dinanath Pathy ( 2007) ; and one by Dr Ratna Roy Neo Classical Odissi Dance (2009). Prior to these publications, there are also two more books by foreign dancers, one by a French dancer and scholar Tara Michel on Hastas, hand gestures (1984), and Frederique Apfel Marglin’s Wives of the God-King (1985). Besides, there are also several chapters on Odissi in various books on Indian classical dances and articles in various academic journals and magazines, have covered most of the information given in the present book. A lot of work has been done in Odissi besides Mohan-ji’s researches. As a student of history and working on Odissi book, if as a coauthor, the issues like globalization and Odissi, the reach of Odissi beyond borders of India, the four major International Odissi dance conferences, the issues discussed in ‘Odissi stirred’ conference at Kuala Lumpur which Ashish attended, et al would have brought the book on par with latest developments. There are other aspects and complex issues relating to Odissi, presented succinctly in book like Re-thinking Odissi could have found reflection in the survey and updating of the book. Mohan-ji was an unparalleled chronicler. The information Mohan-ji has given in the book indeed is priceless, even when it suffers from excess of it. Why it appears so is on account of the material already in public domain with so many books, listed in earlier paragraph. Therefore this book has arrived two decades late and appears dated. Going through the text, I notice that Mohan-ji and Ashish have not mentioned anything about Sabdaswarapata tradition, which is the hallmark of Guru Deba Prasad Das gharana. A wealth of information of Sabdaswarapata was collected from Kumbhari village in 1966, which disciples of Guru Deba Prasad Das like Durga Charan Ranbir and Gajendra Panda have further developed and it has found excellent representation in Ramli Ibrahim’s choreographic works. Similar to kautvams in Bharatanatyam and kavits in Kathak, it has been an important element and part of Odissi format. The developing format of Odissi, like a Margam in a dominant form like Bharatanatyam, (covered in chapter ‘On and Off Stage’) deals with it (pages 167 to 171) and looks ‘dated’ as what is described about Batu number has today undergone a metamorphosis as it contains nritta only, incorporating sculptural representations of dancers playing upon musical instruments like flute, veena, manjira and mardala. It is in this format that Batu is performed during past 40 years. Also when we look at Odissi during past twenty years we find that many changes have taken place in presentation of Odissi and also the music which accompanies Odissi. To wit, Madhavi Mudgal uses practically Hindustani music in which she is well versed and her brother Madhup Mudgal has composed several compositions for Madhavi’s new choreographic works. The references to Bandha Nritya by Mohan-ji are cursory. The Bandhas are salient features of Gotipua dancers’ repertoire. In ‘attendance annual’ which Ashish edits, he has carried a brilliant article by Aloka Kanungo on Bandhas. (highlighting Traditions of East 2007). This could have supplemented the information to fill in the gaps. The group works of Guru Gangadhar Pradhan, Durga Charan Ranbir and Bichitranand Swain have come to the fore. As a matter of fact, Deba Prasad Das and his disciples Durga Charan Ranbir and Gajendra Panda’s work has found prominent place in excellent choreographic works of Ramli Ibrahim and his dancers under the banner of Sutra Foundation based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Ramli’s regular visits during past ten years have contextualized Deba Prasad gharana well in Odissi. Disciples of Durga Charan Ranbir succeed in profiling another important face of Odissi with amazing Sabdaswarapata tradition. This could have been emphasized in the survey in last few pages. There is no information about the incorporation of tantric tradition (Chaushashtha Jogini temple illustrations are found in book with the various manifestations) into dance by Guru Surendranath Jena. Alessandra Y Lopez, a scholar teaching at Roehampton University in London, has brought out a special DVD tracing the origin of this tradition and performance by Pratibha Jena, daughter of late Surendranath Jena. She has also written about Chaushashtha Jogini and tantric tradition. Ramli Ibrahim has in his choreographic works presented these tantric elements brilliantly. The critique of Odissi Research Centre, which Kum Kum Mohanty succeeded in establishing at Bhubaneswar (1984) where her Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra lent his services and guidance for more than a decade along with violinist Bhubaneswar Mishra, seems ill-informed, as it does not take into account excellent work the Centre has done. During Kelubabu’s tenure and others who joined the Centre, very significant seminars were held for academic studies, nomenclature of technical terms, publications of books like The Odissi Path Finder, the first major attempt to notate Odissi dance movements scientifically and coining of a new terminology for Odissi to illumine the nature of the movements and basic dance units; and most precious documentation, in terms of recordings of dance of the architects of Odissi, including Pankaj Charan Das, Deba Prasad Das, Kelucharan Mahapatra and others are not credited properly as important work of the Centre. The seminars on Odissi music organized by the Centre were an eye-opener. The Centre had undertaken most fundamental work of music notation. The Centre undertook the completion of notation of Kishorechandranana Champu kavya based upon the living tradition. The Centre has released cassettes of the same. I have attended some of those seminars and consider the contribution of the Centre very important. The recordings and interviews of Gotipua dancers, performances during Jhulan Jatra (as Chandan Jatra festivals were discontinued), recordings of Sakhi nach and several traditions of Pala performances, Sahi Jatra and folk dances are a rich treasure trove for which Orissa shall remain indebted to Kum Kum Mohanty who combined her experience as a bureaucrat, having worked in Indian Postal Services and a brilliant exposition of Odissi dance form successfully. All institutions like Odissi Research Centre face several constraints and restraints and criticism. The Centre’s long term contribution needs to be recognized. The other criticism Mohan-ji has made is about the Konark Dance Festival started by Odissi Research Centre, ‘as cue from Guru Gangadhar Pradhan’s Festival’ which he had been holding at his Konark Natya Mandap, nearby at the great Konark temple. No one had to ‘take a cue from Guru Gangadhar Pradhan’s festival.’ The Department of Tourism, Govt. of Orissa and other State Governments had also with the success of Khajuraho Dance Festival, planned the Dance Festival at Konark temple, other festivals like Elephant Caves in Maharashtra, Modhera in Gujarat, Mahabalipuram in Tamil Nadu, and several festivals at various temples like Somnath, Halebid, Pattadakkal and Hampi in Karnataka. Dance festivals at historic temples are a part of the movement. Blaming Kum Kum Mohanty as an officer, monopolizing, and performing with Odissi Research Centre’s troupe at the Konark Dance Festivals appears incorrect and unfair. Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra used to specially choreograph group works for the Konark Dance Festival for many years and had during one year his three star disciples Sanjukta Panigrahi, Kum Kum Mohanty and Sonal Mansingh, perform together in one of his choreographic works. I have attended several such festivals for many years. These facts do not seem to meet with the criticism quoted from the media and press. The Centre is rightly re-christened with Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra’s name as Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra Odissi Research Centre. Now let us have a look at the visuals. Like Mohan-ji, Ashish is a very good photographer. One loves to browse the book for the illustrations it contains. All coffee table books with visuals succeed in making readers browse it, look at the photographs and also at times while browsing, read the captions. Mohan-ji had a knack of capturing dance movements. The unfortunate flaws of this book are incorrect captions, which form a major drawback of an otherwise a well chronicled book. It takes away from the importance and correctness of the illustrations and therefore the relevance of illustrations, which are supposed to complement the text. Few examples: On page 21 the photo is identified as Lingaraj Temple complex and the enlarged photo of the same monument on page 32 is mentioned as Rajarani temple. It IS of Rajarani temple and the very first chapter starts with a wrong identification of the temple as Lingaraj Temple. On page 26, the caption mentions ‘Baital Deul temple’ only and is repeated twice, once in colour on page 84 with image of Lord Shiva with caption ‘Suryanataraj at Baital Deul temple’ and partially in black and white on page 78 with the same caption where Surya’s image is not there as it is on pages 26 and 84. There is no nomenclature found as ‘Suryanataraj’ so far, in any book on sculpture and architecture. The caption should have been Lord Shiva with ‘urdhva lingam,’ a prominent feature of Shiva images in shikharas of the temple. The image of Surya is seen in the photograph on page 26 and in colour on page 86!! But it is not on page 79. On page 34, the most visible temple in Bhubaneswar is that of Lingaraj temple and it has caption as ‘Bhubaneswar temple complex.’ On page 64, caption reads ‘Konark temple detail.’ As a matter of fact, it is of Ardhanarishwara sculpture of Lord Shiva on the wall of jagamohan part of Parashurameswar temple of 8th Century A.D. The most serious mistakes are on pages 66 and 67. On page 66, the basic Chauka stance of Odissi which is seen in the two sculptures above and below are from Parashurameswar temple of the 8th Century A.D on the wall of jagamohan section and are not of ‘dancing girl, Konark relief’ (top and bottom). On page 67 the caption reads simply ‘Musicians and Dancers panel, Konark,’ which it is not. It is from Brahmeswara temple of 10th Century A.D, showing a dancer in a pose of Parshwamardala, playing on the side of the drum. Such mistakes detract the book from a serious study of sculptural evidences and show lack in depth, observation and therefore incorrect. On page 85 there is a color photo of a dilapidated temple with caption ‘The group of Four Temples.’ Which four? Then opposite Jagannath temple at Puri with white lime plaster, there is a photograph on page 88 of a female playing upon a musical instrument with caption ‘Konark temple complex’ which is vague as many captions of sculptures throughout the book are. It is not from Konark temple complex but from Mukteswar temple. There are stylistic differences of sculptures in the temples over various centuries and therefore the photographs of the sculptures need to be placed with relevance. Alas, the book gives an impression of an album of photographs. The photograph on page 105 has a caption ‘Details from Mukteswar temple.’ Why it is placed there one does not understand. It is a rare sculpture of Parvati dancing and no information about it is given along with the caption. Mohan-ji has mentioned about that sculpture in the text. Ashish should have read the text carefully and after identifying sculptures correctly, the photos should have been placed as illustrations closer to the text. The two colour photographs on pages 112 and 114 of boys in loin clothes, supposed to have been taken for Chandan Jatra Festival, when the proxy idols used to be taken on a boat in Chandan pokhri, tank near the temple, do not do justice to the description of the festival of Chandan Jatra, as the boys are seen posing for camera on a boat with a red canopy. The boat with red canopy was used for dance of the maharis, when idols were taken round the Chandan pokhri. The boat with white canopy was used for gotipua dancers to perform on the boat. This has not been mentioned. On page 110, of the three photos in black and white one on right hand side below has a caption ‘Sonal Mansingh in Chandan yatra hamsa.’ It makes no sense. Sonal Mansingh did not ever perform at Chandan pokhri on the occasion of Chandan Jatra. Also dancers do not perform on a boat except the maharishi and the gotipuas. As a matter of fact, that photo is obviously from the series of Sonal’s photos of Mangalacharan on pages 164 and 165. The caption for each photograph reads repeatedly ‘Sonal Mansingh depicts Mangalacharan.’ There too the order is wrong. The photo on page 165 on bottom on right is of Bhumipranam which should be on page 164, as the first photo showing the beginning of the series of photos as dancer is shown touching the earth with her two palms, then as photos on page 164 show, she lifts palms to the eyes and then raises above head. The photo on lower level with folded hands should have been placed last on page 165 to complete the series. The photo on page 196 is of Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra and his wife Lakshmipriya. These are already published in Ileana Citaristi’s biography of Kelubabu, and elsewhere by Kelubabu’s son Ratikant Mahapatra. Unfortunately the captions here are once again wrong. The duet by Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra and Lakshmipriya is captioned ‘Kum Kum Mohanty and Krushnapriya in Krishnagatha’ (The correct photo with that caption is found on page 179)! On page 197, the photo below has caption ‘Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra and Haripriya.’ It is not Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra with Haripriya but with his wife Lakshmipriya. There seems to be confusion about the person in some photographs when one sees carefully the photographs, and identifies the dancer with the accompanying caption. For example, double spread photograph on pages 268 and 269 of young dancers studying Odissi at Nrityagram. The dancer on the left taking class in the open is mentioned as Protima (Bedi). She is not Protima (Bedi). Another double spread photo on pages 308 and 309 has no caption at all. A black and white photo of Kum Kum Lal on page 298 has a caption ‘Kelucharan depicts virihini’! On page 304 a photo of Oopali Aparajita (on right) has a caption ‘Oopali Aparajita nayika holding a bird and a fish’! On next page, a colour photo of Priyamvada Mohanty reads ‘Priyamvada Mohanty depicts a drishtibhav.’ What drishtibhav? The inexactitude also prevails in captions for the photographs of the dancers and appears equally vague. Sanjukta Panigrahi’s photo has a caption ‘Sanjkuta Panigrahi depicts Vrikshabhaveshu,’ which is not explained that she depicts a tree. These Sanskrit terms require explanations. If I have taken such pains at length to draw attention to innumerable errors and short comings of the book in terms of visuals, I have done so with a hope that in future Ashish would take great care and avoid serious mistakes. Despite all that I have mentioned, Mohan-ji’s work shall remain most valuable. Dr. Sunil Kothari, dance historian, scholar, author, is a renowned dance critic, having written for The Times of India group of publications for more than 40 years. He is a regular contributor to Dance Magazine, New York. He has to his credit more than 14 definitive works on Indian classical dance forms. Kothari was a Fulbright Professor and has taught at the Dance Department, New York University; has lectured at several Universities in USA, UK, France, Australia, Indonesia and Japan. He has been Vice President of World Dance Alliance Asia Pacific (2000-2008) and is Vice President of World Dance Alliance Asia Pacific India chapter, based in New Delhi. A regular contributor to www.narthaki.com, Dr Kothari is honored by the President of India with the civil honor of Padma Shri and Sangeet Natak Akademi award, and Senior Critic award from Dance Critics Association, NYC. He is a contributing editor of Nartanam for the past 11 years. Response 340 pages and over 400 pics in a tome is bound to have a few errors. Even the Taj Mahal has one minaret that's crooked! Unfortunately for me, after several proofs, and showing to scholars and authorities on architecture in Orissa and outside, few errors crept in captions. After ten years of plodding and several proofings, I was also abroad 2 months when the book went to press, so the critical input of last minute supervision could not take place. The book is about history and heritage of the form, written by foremost dance authority, Mohan Khokar. Be that as it may, the book has been appreciated by scholars and connoisseurs like Sanjukta Panigrahi family, Zohra -Kiran Segal family and Lalit Mansingh. Orissa has a unique multiple id in nomenclature as we see all the time. The Bhubaneswar temple complex is a generic term for Ekamara Kshetra where Lingaraj Temple complex is. Having worked for INTACH 2 decades ago in restoring the area, some of that terminology has crept in. Captions on some pages are twice and got inverted (197 and 179), evidently a typo. Sanskrit common words are understood by most dance readers. The book is certainly dated because it is about history. It is also not about seminars and events that are a dime a dozen nowadays. This book is a recap of thousands of years of Orissi, its provenance, players and persons who have contributed significantly. In all humility, no book can be final, only Brahma or his consort Saraswati can write one. - Ashish Khokar (Nov 30, 2011) Post your comment Unless you wish to remain anonymous, please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted in the blog will also be featured in the site. |