|

|

|

|

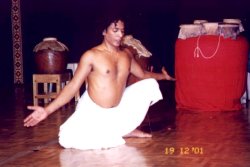

CHOREOGRAPHY IN THEATRE by Veenapani Chawla Natya Kala Conference 2001- December 19 |

| Sep

2002

Any discussion on the role of choreography in Theatre has to be preluded by identifying the nature of its signifiers. And one could say the signifiers in theatre are perceptual, they are visual and auditory. If one goes beyond the literary conception of theatre, goes beyond a view of it as being basically dramatized literature, texts, words, one accepts that of all the arts, theatre's signifiers are more perceptual, for it mobilizes a larger number of the axes of perception. It contains within itself the signifiers of the other arts; it can present visuals to us, it can make us hear music, it involves linguistic audition, it involves movement and real temporal progression. And in comparison to cinema, which also has a similar numerical superiority of signifiers over the other arts, the perceptions that the theatre offers to the ear and eye are inscribed in a true space. The theatre involves real persons on the same scene as the public. Presence is the only reality in theatre. The cinema on the other hand accommodates every reality except the presence of the actor. |

And I ask myself, what then is the difference between dance and theatre? For both employ other arts and central to both is the live presence of the performer. Before proceeding to answer this question let us consider the two principal radical positions in the arts today. One position recommends 'purism'. The other recommends the breaking down of distinctions between genres so that the arts eventuate in one art, which would consist of many different kinds of behavior going on at the same time. Both these positions support the quest for a definitive art form. The purists believe that an art is definitive if it is rigorous and fundamental. Those proposing a synaesthesis suggest that the most inclusive art form is the most definitive art. And as theatre can be anything and everything, it is the favorite candidate for this role of summative art.  Unlike theatre, dance is a specific art. And the predominant behavior of dance is movement; the other arts are conscripted by it only so as to serve this predominant behavior.  In theatre, the other arts employed are fundamentally there as signifiers. Each one of them acts as a text or seeks to convey a meaning, characteristic to it. Each one of the performer's instruments of expression, the word, the physical image, the aural sound, is sovereign in expressing a concept from a particular angle or a particular point of view, and each mode of expression has its own characteristic contribution to the unpacking of the central concept, which the other forms of expressions cannot replace. Thus linguistic audition imparts an intellectual point of view, while visuals provided by body images can convey the optical equivalents of psychological spaces. The moment dance is willing to admit a plethora of other arts as varied signifiers into its behavior it crosses over into the realm of theatre.  In the traditional theatre of Koodiyattam, an example of a particular art becoming a signifier in the theatre is that of music. The most striking element in Koodiyattam music is the rhythm. The function of this rhythm is not merely to support the performer but to suggest images, emotions and events, which are not conveyed by her other behavior on stage. The rhythm therefore becomes a way of conveying significance, which cannot be duplicated by another form. Thus these two elements: 1) the inclusion of other arts as signifiers and 2) the live presence of the performer, determine the larger question of our aesthetics of the theatre. And out of our aesthetics of the theatre emerges the particular role of choreography in the theatre. |

| In

the context of the above discussion therefore the case for the role of

choreography in theatre rests on it being employed as a signifier in that

genre.

Space, its arrangement in relation to the performer and inversely the arrangement of the performer's behavior in relation to space, so as to convey significance, is what choreography is all about. Theatre recognizes three kinds of spaces. There is a sense of the inner psychological space of the performer, the external 'real' space, which she shares with the audience and a larger cosmic space. These three spaces are a movement from subjectivity to objectivity and then to a qualitatively superior subjectivity. And arranging for the performer to relate these spaces in a meaningful way for a shared experience with the audience is the essence of choreography. Koodiyattam performance deals with the expression of these three spaces, through mukha abhinaya, which expresses the most intimate inner space, through mudras, which communicate to the objective space shared with the spectator and through vachika, which through sound fills cosmic space. Contemporary theatre has much to learn from Koodiyattam in its fundamentals relating to choreography. For this form also demonstrates that the external structures and stances and gestures that the performer gets into, aid her to tap her psychological inner spaces and thereby relate these inner spaces to her apparent behavior in the 'real' external space. For the way a performer stands, walks and gestures, impacts her psychological state. The arranged language of external bodily behavior is therefore a foundation. It is a key to opening up the performer's inner spaces so as to allow them through her manodharma / improvisation to connect and relate to the external space. The Tantric tradition of the seven psychological centers, which are also connected to the centers of energy of external bodily behavior, is the principle on which this practice is based. By relating the external centers of energy, to these psychological centers we allow for one space to relate to the other. We have so far argued for the role of choreography as a signifier in theatre and contextualized its theatrical relevance in the concept of synaesthesis. However there is another equally persuasive reason for its role in theatre. This stems from the second specific mentioned above, which distinguishes theatre from other art forms- the live presence of the performer. Such a presence, begs for a physical behavior on the performance space, which enhances the sensorial impact of the performer. It begs for a behavior, which emits an energy that seduces the spectator into the performance. And consequently it implies that the performer cultivate the external instrument of her body to the largest degree and develop a language of bodily communication, which can then be arranged in real space. And in a theatre, where the performer has elevated her consciousness through a cultivation of extra daily bodily behavior, this enhanced energy of the performer reaches out to the consciousness of the spectator and through a contagion of consciousness, it raises it beyond itself to a more cosmic consciousness /space. Rasa and catharsis both aim to achieve this elevation to a heightened space in the spectator. |

Veenapani Chawla is one of the foremost experimental theatre exponents of modern India with a multi-faceted career. She has devoted her life to theatre, acting and directing from 1979, and finally founded her own company Adishakthi in 1984. A Greater Dawn, Impressions of Bhima, So What's New, Khandava Prasdha Agniahooti are some famous works directed by her. In 1997 she received a one-year grant from the IFA for the project A Dialogue Between Koodiyattam, Nangiar Koothu and Contemporary Theatre under their Arts Collaboration Programme. Bhrannala was the result of the collaboration. Ganapati is the result of a collaborative work supported for a one-year project by the India Foundation for the Arts and the Sir Ratan Tata Trust on "Music as a Text in Koodiyattam and Contemporary Theatre". Veenapani has presented several papers and been nominated by the Department of Culture, Govt. of India as an expert on the committee for selecting candidates for Fellowships in the field of folk, traditional and indigenous arts. |