|

|

|

|

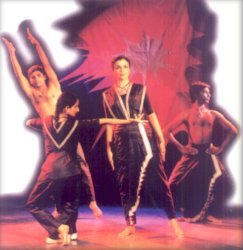

ADAPTING TRADITIONAL THEMES IN DANCE - THEATRE by Anita R Ratnam Jul 2001 (Anita Ratnam won the best lec / dem award for this paper in December 2000 at the Music Academy, Chennai, India) Dancing and acting are one and the same art. They are but the rhythmical movement of the human body in the space, caused by the creative impulse to represent an emotion by the expressive means of one's own body, and with the intention of pleasurably releasing this inner drive by setting other people in the same or similar rhythmical vibrations When one trains in the tradition of classical Indian dance, one unconsciously shapes one's body and mind into that of an actor. To play a variety of roles simultaneously on the stage, which a dancer does as a natural process of learning and performing, comes closer to the concept of 'theatre' than 'dance'. After all the word 'natya' itself denotes theatre. Dance is qualified in Sanskrit as 'nritya'. For the purpose of this session and keeping in mind the erudite audience that attends, I will elaborate my ideas of how the worlds of dance and theatre unite in my choreography. Taking three examples from group and solo works, I will attempt to explain how the ideas of theatre, the art of suggestion, the power of minimalism, the strength of silence, the inclusion of spoken words and Vedic chants, the contrast of natural movements juxtaposed with the stylization of the classical technique and the use of certain props and materials designed specifically for the purpose enhance the vision of my choreography. As we live in a new century and engage with the coarseness of everyday life, the beauty and nobility inherent in our ancient arts are all the more vulnerable. The invisible and insidious currents that run through our lives seek to destroy the possibility of imagination, abstraction and the power of ritual. Today the theatre of trouble, of doubting and of alarm seems truer than the theatre with a noble aim. The dancer, actor and choreographer search vainly for the sound of a vanished tradition and critic and audience follow suit. We have largely forgotten silence. It even embarrasses us and we clap our hands mechanically and shift uncomfortably in our seats because we do not know what else to do, and we are unaware that silence is also permitted, that silence is also good and that most importantly, silence is part of the performance structure. In theatre, silences are not uncommon. The pauses between dialogue, the entrances and exits of actors or dancers invoke silence. But in Indian dance, we do not have, in fact we never have absolute and total silence. The sound of the drone or the tambura is always there in the background, filling the space and time with its vibrations. Natural movement juxtaposed with stylized formalism makes for interesting contrasts and adheres to the principle of two sticks rubbing together. In classical dance, we are already used to the idea of Dance Drama, but if the principles of theatre are truly applied they can create many interesting forms of combustion. Contrasts, individual movements at various levels instead of all the dancers doing the same movement in multiples, the stage space used and 'blocked' like a director would do in theatre without the frontal proscenium obsession with classical Indian dance of today - all these make for the stuff of interesting viewing. In working with the idioms of dance and theatre and knowing that the source and textual material for my work would be from traditional texts, I had to set out to create a world where the experience of dance and theatre would meet, sometimes collide, may be provoke but never bore. In the ideas of theatre I found the possibility of a new form, which could be the container and a reflector for my impulses as dancer, actor and choreographer. This search would revisit old ideas embedded in the classical texts and reshape them for myself and for the audiences of today. Essentially all dancers and actors work alone. They share the solitude and the vulnerability of creating and making critical choices in total isolation. The audience also needs to make a leap in choice and judgment when they view new images and suggestions. After all, Bharatanatyam is supremely qualified as the example of suggestion and abstraction by a solo artiste. The whole world of ideas and a host of people and their mannerisms can all be suggested by a flicker of an eyelid, a flourish of the hand and the attitude of the body. However, the classical dance framework does not allow for a juxtaposition of images in a different rearrangement of sound and silence. My first example is from 'Gajaanana' the story of Lord Ganesa in which in the first scene Parvati combines the sweat and dirt from her body with the mud and essence of the earth to create a young boy-child. Using the idea of clay being shaped into a human form, the ensemble will use natural and stylized movements along with the traditional 'chol' of Bharatanatyam to visualise the physicalisation of the human Ganesa. Starting with near silence and no specific tala structure of time cycle like a kala pramanam, this section uses the idea of multiple level, diagonals and circles in the choreography. The idea of center stage is broken initially with no movement taking place in the customary center spot. There are no lyrics and the entire act of creation is conveyed through the energy of the movements and the sound of the ganjira. In another section of the same production, the elephant head is placed atop the body of the dead boy-child. Siva blesses this new form and Ganesa is reborn. The use of Vedic chants uttered by the dancing ensemble themselves wrests the 'voice authority' from the traditional dance orchestra and invests the performers themselves with the dual role of dancer and actor. By actually uttering the syllables to which they move, the dancer-actor empowers herself / himself with the choice of sound and movement. The elephant head of Ganesa was specially designed by using Tamil mat-weaving techniques and adopting them for the creating of stage props including the backdrop and the accessories worn by the ensemble. The process of chanting and dancing required training and took a long time to coalesce into a smooth whole. The use of breath employed in dance and in acting is totally different. These days, dancers are rarely trained in this aspect of voice and singing unlike classical dancers of yesterday who were experts in the music traditions to which they performed. Once the chants are complete, the space is then punctuated with a traditional dance 'kavuthuvam' praising Ganesa. The central motif of the dance cluster is kept immobile for the entire duration of the kavuthuvam except for the gentle swaying of the elephant head. When one uses Sanskrit, Tamil, drum syllables and sounds familiar to our ear, the cadence and the process of cultural memory reasserts itself. Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, Carnatic music - these are part of a soundscape which is recognizable. What happens when we change the formula and introduce the idea of 'rap beats' to Tamil lyrics or the concept of softly spoken whispered 'chollu' to movement? What if the language itself changes to English? How do we translate traditional ideas on the stage within the framework of a creative effort using dance images with the vibrations of a language alien to the classical movement traditions?  The next excerpt is from one of our recent productions called 'Daughters of the Ocean', which is a stage adaptation of a contemporary book. Delving into the myths of the three pan-Indian goddesses Durga, Lakshmi and Saraswati the choreography involves contemporary story telling in the tradition of 'katha'. Intermingled with creative movements culled from extensive improvisation and the classical 'tala' system of Bharatanatyam, the work will not show the classical dance imagery of the three goddesses normally seen in Bharatanatyam. Instead their qualities will be enhanced and imaged - the focus, strength and energy of the arrow to denote Durga, the abundance and auspiciousness of Lakshmi and the creative flowing stream of Saraswati. The idea of abstraction is used in the power of suggestion and the open canvas of opinion. We will begin with Durga who is envisioned as Yoga, as sharp and direct as an arrow who was created for one single purpose and who never wavered from her goal. To annihilate Mahisha was why she was created and destroy him she did after a long and bloody battle. The images of an arrow, of strength, of force, of directness and of a goal are what we use in this section. Immediately we follow with the section of Lakshmi who emerges from the great milky ocean after the great churning. To see Lakshmi is to feel peace, auspiciousness and calm. The quality of awareness is what we have sought to bring out which meant an awareness of each other as dancer / actors. In both sections the idea of symmetry is abandoned for a more improvised and individual approach. Each dancer does a series of movements only keeping a space pattern in mind. Each time the choreography is different except that we all know where and when we have to bring the images to a conclusion. After Lakshmi we move right into the section on Saraswathi who was once a river and who now flows silently underneath the surface of the earth. Saraswathi the curious goddess who always questioned was cursed to become a river and she flowed in so many directions that even Brahma could not keep track of her movement. Here the idea of tipping the balance, of a river flowing ceaselessly all the time and leaping towards its final goal are explored. The story telling sections were created after the dancers came up with a set of movements to the adi structure of 'avartanams'. They were then arranged in patterns and the spoken sloka device was reintroduced. The use of the prop like an ocean drum while narrating and the theatrical device of the narrator / actor saying the rhythmic syllables to control the dance movements invests the performing group with the power and ability to create their own rhythm pulse and desired effect. In fact, the absence of the regular dance-orchestra compels the movement and the action on the stage to be even more forceful and arresting since there is no accompaniment to either distract or compensate for weak choreography. In the final example, I will use an excerpt from one of the latest productions 'Nachiyar', the story of Andal. In the last verses of Andal's yearning for Sri Krishna, she is desperately irrational and surprisingly erotic in her imagery. In the traditional mode of research and choreography, I would have used several ragas to enhance the pathos that Andal felt and emote like the classical Bharatanatyam dancer would. Instead, I have chosen to use silence in its complete sense and the presence of an actress who would be my 'voice' for the section. Without any tambura for registering the scale, Revathy Sankaran uses the power of the Tamil language without any appendages of music and tala. The use of language in its spoken form and Andal's response to her in the space is what gives this section a real meeting of the worlds of dance and theatre. Theatre is the art of the fulfilled moment. If we accept life in the theatre to be more visible and more vivid than the outside, then we can acknowledge that it is only through the actor - dancer that the act of reducing space and compressing time creates a concentrate. The idea of dance-theatre or the word itself was coined in Europe in the seventies to describe the work of radical choreographer Pina Bausch. To unite the worlds of dance and theatre is not a unique concept in India. It was the tradition of dancers to sing and perform simultaneously. Actors on stage could sing and enact their dialogues as well. In this way, contemporary Indian dance and theatre are actually moving closer together to unite in the holistic version of 'natya' or total theatre. While these labels concern choreographers and performers little, they seem to be more and more necessary for the audiences, the media, presenters and funders in order to understand and describe the work. While Indian audiences are familiar with the term 'dance-drama', which represents an ensemble work on a thematic subject, the idea of 'dance-theatre' is often unclear and blurred. Due to our unbroken history of iconography and imagistic expression, the Indian / actor / dancer has a much more difficult task in sifting through the layers of theology, religion, ethics and cultural constructs of the received tradition. To dissect the sophisticated movement framework of classical dance in its interrelation to space, time and energy is not a simple exercise. To experiment with the aesthetic possibilities inherent in the elements of the classical movement, to think of time not just as beats and patterns, but a dimension of movement that could be projected or diminished, to acknowledge that movement itself has no traffic with morality and does not yield to logic - these are some of the challengers that faces the world of Indian dance-theatre today. The mind is also a vital muscle in this process. Finally, when a movement succeeds, neither the mind nor the body is separate. |