|

|

|

|

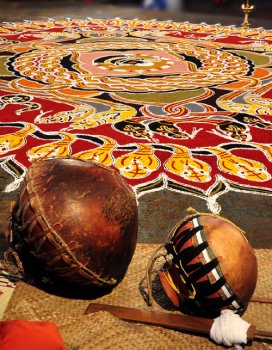

Sarpam Thullal, a mystical dance, an experience - Padma Jayaraj, Thrissur e-mail: padmajayaraj@gmail.com November 22, 2010 As India celebrates Diwali, central Kerala revives a folk ritual practice in the Malayalam month of Thulam. Serpent worship used to be part of folk religion in this tropical land. Today, it is alive as a ritual ceremony for wellbeing and prosperity, with the message of environment conservation. There are snake groves attached to olden homesteads where female priestesses safeguard the snake as a deity. On a rain swept afternoon we meandered through a pot-holed road to the heart of a hamlet in Kerala, in the South Western state of India. I wondered about the fruitfulness of braving the torrents. Could I ever peep into the heart of a ritual tradition with the analytical frame of a modern mind? Yet the journey could be worthwhile, as I had only heard about this ancient ritual practice and never seen it performed. Supernatural practices have been part of primitive culture. Many tribes all over the world in the past worshiped animals and plants for different reasons: out of fear, as symbols of fertility, prosperity and so on. Ancient homesteads have retained their shrines dedicated to snakes as part of Nature worship. And at these shrines, Sarpam Thullal is an annual performance by the members of a special community called Pulluvar, a community of village minstrels. Legend says Parasurama, who brought forth the land of Kerala from the seas, has given the Pulluvars the right to live by worshipping the serpent gods that are protectors of the land. Now the pullavan pattu evokes nostalgic memories perpetuating an eco-myth. However, some Pulluva families take care to hand over the song tradition, the ritual dance and Kalamezthu, the art of drawing a ritualistic rangoli using herbal colors, down the line. The loud 'tum tum' emanating from an earthen pot with a string attached, announced the event. Roused by a music that plucked at the heartstrings, people from around gathered at the venue. A small group of rural folk, most of them the members of a single extended family had come to take part in their own special affair in their ancestral home. A group of three men trained in their specialized art of drawing were giving finishing touches to an elaborate picturesque design. Kalamezhuthu is an art itself. Drawing stylized figures of gods and demons that tell of lore and legend for temple festivals are part of the mystical rhythms of folk-art. The carpet like designs are made up of herbal powders. The colors used are white, black, yellow, green and ochre that give a rare vitality with shades of old world magic associated with primitive religions.  Sarpa kalam is the large pictorial arena where this ritual drama enacts its mystique. From the elaborate pattern of vibrant colors, hooded snakes rise up larger than life. The knotted, twining serpents cast a spell under the light from the bell metal lamps. The leafy decorations flutter around the kalam. In deepening dusk, this is sacred ground indeed! Nearby, the small shrine dedicated to the snake is lit like a little temple.  It was growing dark. Two women sang an invocation striking the chords of the kudam that echoed the heartbeat of the night; the lonely aching of the naga veena mingled with the music of rain; cymbals chimed resonant. The young women of the host family holding thalams (brass-plates with flowers and lighted lamps) brought the idol of the snake in a procession from the shrine to the kalam. The crowd waited eager-eyed. The night outside throbbed; the lights glimmered; the rain whined. The leafy decoration of the venue swam in the wind like snakes, their shadows moving in the gloom. The pictures of multi-colored, coiled snakes, and the moaning of the stringed instrument created a strange feel. The songs sprang from the immeasurable depths of our racial memory. Images, long buried, were bobbing up and down the river of life flowing inexorably from the beginning of time. And the velvet music flowed melting everything. Soon, one of the men began to move around the kalam with flaming torches in his hands. Thiri uzhichil is a dance that simulated the eerie movements of a hooded snake. His black head, black finely cut beard, his gleaming eyes, and his rhythmic movements slowly cast a spell. Over the large carpet like design, the twining forms seemed to move in harmony with the movement of the man and the rhythm of the chant. Snakes seemed to slither…. here, there, everywhere. Darkness impenetrable, flickering lamps, a hypnotic dance with fiery balls, wind and rain among the trees…The musical notes mounted, strange, turbulent, insistent, and plaintive. It floated out upon the night losing itself in the rain. Not knowing why or how, it touched my untutored heart. I sat compelled and involved in an electric atmosphere. As I listened, some strange wonderful magic made something within me stir, flutter, and then soar.  The young girls who sat cross-legged among the patterns of hooded snakes began to sway. It was surreal: their closed eyes, their trembling hands, their flowing hair, and their sleepy state. Their swaying bodies moved everywhere as if the pictures of the snakes had risen alive. Hysteria shook some other women of the family. One rushed from within the house as if in sleep, took the silky white bunch of the buds of the palm tree, mumbling visibly and began to sway and dance. They wiped the kalam off by dragging their bodies, pulled the leafy decorations, swayed and moved around. It was a snaky world! Questions were asked; answers given; futures told; problems solved - all in trance! The whole scene seemed part of a dream, a voyage beyond space and time. The songs, the singers, the dancers, and the viewers were transported into a world of tuneful magic with the fragrance of myth, fact, and fantasy. And the night poured out its soul in melodic resonance. The snaky figurines crawled towards the shrine. People poured water; the unconscious women were carried off. The spell broke. I opened my eyes into the world of reality, gazed at the darkness of the heavens, and felt my tears mingling with the raindrops. The stillest hour of the night had come. And sleep stayed far away from me. A pale moon hung low in the sleeping sky. Here is the cultural equivalent to the history of a community. The Dravidian strains of our painting, of music, of musical instruments are deeply ingrained here. Here lies the collective heritage of our community: a reverence for Nature, a philosophy of co-existence. I went there with doubts and conflicts. But the night brought me a revelation. I recovered what was lost - the ecological balance we need, a retreat from the sick hurry of our times, a chance to contemplate the glory of a lost vision that held all created things sacred. Driven by curiosity, I went to meet the professional troupe the following morning. A young man, his mother, wife and two uncles carry on the tradition of their family with utmost devotion. They are busy throughout the season. It was their great grandfather who collected all the songs, handed over by word of mouth. And they have kept some materials that research students of folklore care for. I asked them about the mystery of trance. But, they told me of a hundred stories that my childhood memories recalled. On my way back, I stopped at my sister's house. Her husband, a practicing psychiatrist offered some explanation for this strange phenomenon. He talked at length of the power of the subconscious, the complexity of human psyche, of racial memories encoded in the genes, of some being susceptible to hypnotism, of mass hysteria, of telepathy, of clairvoyance…When I set out, the rains had almost stopped. The sky smiled and there was the promise of sunshine. Padma Jayaraj is a freelance writer and a regular contributor to narthaki.com |