|

|

|

|

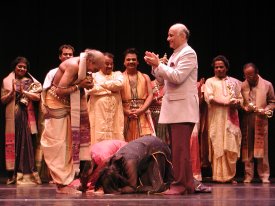

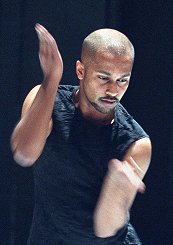

Performing arts in the Diaspora: Constricting hybridity by Rajika Puri, New York e-mail: rajikapuri@yahoo.com Reprint from SEMINAR, June 2004, courtesy Tejbir Singh (editor) September 5, 2004 August 2000: The first inter-national festival of Odissi, featuring three days of performances, seminars and lecture-demonstrations by major gurus, dancers, musicians, critics and scholars of the form is held in Washington, D.C. May 2001: Thirty-five young Bharatanatyam dancers, members of a locally based company, perform Jataka tales to the music of Rimsky Korsakov and Tchaikovsky played by the hundred-piece Chicago Symphony Orchestra. May 2002: Akram Khan, a Kathak-trained dancer, nurtured by the British cultural establishment as one of Britain's most promising young choreographers, premiers Kaash (with set design by Anish Kapoor, music by Nitin Sawney) in London, prior to being sent on a world tour. June 2002: Andrew Lloyd Webber's production, Bombay Dreams, with A R Rahman's music, book by Meera Sayal, and a cast made up largely of people of Indian origin, opens in London's West End, with its sights set on Broadway. April 2003: Counter-tenor Bejun Mehta sings ‘Guido' in Handel's Flavio at New York City Opera, going on to sing title roles in Giulio Cesare at the Pittsburgh opera, and Orlando at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. April 2003: Five actors play call centre operators in Bangalore while multiple images flash onto several screens above them, in Alladeen, a collaborative project between York-based Moti Roti and New York's Builder's Company, which premiers in Ohio, then goes on tour to New York, Singapore and London.   The majority of producers and funding organizations abroad favoured ‘authenticity'. Thus few Indian artists experimented with their forms, or thought about choreography, composition, or set and costume design. Indian themes in the performing arts were, by and large, handled by non-Indians - playwrights, directors, composers, and dancers who created Indian characters, adapted epic stories, experimented with Indian rhythms, and projected their images of divine dancers like Shiva, Krishna, and Radha. Plum' Indian roles were usually played by non-Indians. Then from the late eighties things began to change, both in India and within the fast-growing Diaspora - especially in the United States and the UK. With the opening up of the economy in India the world of the Indian performing artist also expanded. Now, apart from the government, a performer could turn to business houses as well as the general public to patronise her or his work. ‘General public' included not just the swelling indigenous urban middle-class but also Indians living abroad, and those who were coming back home to work. This public, exposed to non-Indian art forms that expressed a modern world, looked for - indeed ‘demanded' - the same relevance to contemporary life from their own art forms. Dancers, for example, were urged to explore contemporary themes, and to re-think their traditional forms, i.e. to ‘modernise'. Krishna became old hat; the ecological implications of the serpent Kaliya's poisoning of Jamuna waters were ‘in'. As India - and Indians - began to be noticed by the general public abroad, foreign artists turned to things Indian to broaden their own horizons. Different kinds of percussion, spoken drum syllables, and fast tempo vocalisation of swara passages joined the already ubiquitous use of sitar and tabla in flamenco and pop music, and in western film scores. Indian musicians who had to play for a pittance in Indian restaurants were now in demand to record with ‘mainstream' musicians. Indian dancers were invited to perform on music videos; actors of Indian origin began to be cast in TV shows, and for theatrical productions with Indian themes. The term ‘fusion' began to be used both in India and the West. In India, more often than not, it meant Indian music, which had been given a ‘rock', or western ‘pop-music' feel, as when Asha Bhonsle re-issued her old hit songs to a disco beat. With dance, and outside India (in spite of discomfort with the word) ‘fusion' was used to refer to any creative collaboration between different cultures, such as when flamenco dance met Kathak, or Zakir Hussein played a duet with a Japanese shakuhachi flautist. As more and more artists from Africa, South America, Asia, Europe and the US began to interact in performance, the very term ‘world music', which before had referred to music in general from non-western cultures, now suggested cultural amalgams. The New York-based World Music Institute increasingly promoted cross-cultural encounters of which Indian musicians were often the mainstay. As it became commercially viable to present foreign music groups and their recordings in India, Indians had more access to forms like Acid Bhangra and Disco Garba developed among immigrant communities abroad. The major exchange, however, was with the US and UK. Several fascinating musical forms like the ‘Chutney' music of the Caribbean and the pop-folk music of Indic populations in Malagassy and Mauritius (which fuse inherited Vaishnav songs - sometimes in archaic Bhojpuri - with local rhythms) were side-tracked. They did not have general currency - either in India or among promoters of ‘global music' in Paris, New York and London - because the populations from which they stem have little discourse with communities in India or other parts of the Diaspora. In theatre, the notion of a ‘world theatre' drawn from several different cultures grew. India with its treasure of theatrical traditions had inspired productions like Peter Brook's Mahabharata and Ariane Mnouchkine's L'Indiade. Casts were international, breaking down boundaries between different ethnicities: a Nigerian played Bhima, a Japanese actor was cast as Drona. The influence of such productions led to more works, which incorporated techniques, conventions - as well as actors - from Indian theatre. A 1996 French production of Moliere's Tartuffe set in Turkey began with the percussive sounds of a street vendor playing Rajasthani khartaal. A 2000 Hamlet featured three Indians out of a cast of eight. The most significant opening up within the arts - particularly with the younger generation - was the breakdown of the divide between ‘classical' and ‘popular', ‘traditional' and ‘modern'. One evening a classically trained percussionist might accompany bansuri-player Hari Prasad Chaurasia; the next day he could be part of an ensemble led by the cellist Yo Yo Ma. On a third he might record with a pop group for a Grammy Award. Similarly, the same dancer who performed a charming Bharatanatyam varnam one night could the next evening present an innovative dance-theatre piece, which explored violence in contemporary society. The geographical boundaries of the world of Indian performing arts also expanded. Artists spent longer stints abroad, creating works that made an impact on performing arts at home. Many of these works could be seen by fellow artists - either at international festivals, or when the works toured India. As more and more performing artists lived bi-continental existences, they established schools abroad. A new generation of performers emerged who had been trained outside India - and who were taken seriously at home. The dissolution of distinctions between ‘Indian-born' and ‘foreign-born', or ‘Indian-trained' and ‘foreign-trained' reflect a commonality among performing artists in India and in the Diaspora. Even if the specific social imperatives that influence them are distinct - and they are - they feed into a common pool that affects practice both in India and abroad. Let us now look at the current state of the arts. First of all, it is important to recognise that the traditional arts are alive and well - because it is these arts, which give an Indian identity to new developments. Also, that they are likely to be around for a long time precisely because they are not frozen in time. Energised by the various influences on them they continue to develop and live in relative ease with the new directions taken by some practitioners. Indeed, as noted earlier, the same person who sings a traditional Carnatic kutcheri concert at the Madras music festival might the very next month do a concert tour with western musicians who accompany her on a church organ, a shanka and a didgeridoo among other instruments. Another contributing factor is a continued adherence to traditional pedagogy, both in India and abroad. Dancers still learn basic steps, components of dances, and a preliminary repertoire common to most styles of a specific dance form like Bharatanatyam, Odissi or Kathak. Musicians are formed in the age-old way by learning raag and taal, the manipulation of swaras and bols, and mastery of specific forms of song: khayaal, thumri, raagamthaanam, thillana. They all graduate with a debut concert and get a seal of approval from senior practitioners. Thus new work, whether in a traditional or innovative mode, comes from a strong grounding in the vocabulary and norms of basic tradition. In the UK and US, the positive value placed on the uniqueness of each immigrant culture leads to the traditional performing arts being well promoted. Government grants and funding organisations support institutions, which maintain and disseminate them among second-generation immigrants as well as members of the society at large. Immigrants, too, make an impact on the state of these arts when they organise festivals - such as Odissi 2000 in Washington D.C., or Bharatanatyam in the Diaspora in Chicago - and invite leading performers, scholars and critics from India as well as from other parts of the Diaspora. The world of an art form like Bharatanatyam encompasses not only Chennai and Delhi, but Birmingham, Chicago, Texas and Perth. These very factors also contribute to change. Promotion of multi-culturalism means that grantors also favour projects involving collaboration with other immigrant groups. Performers are also invited to collaborate with mainstream culture, with modern dancers, symphony orchestras and theatre directors, opportunities, which give them a wider audience, prestige and greater financial viability. The artistic and sociological effects of their interactive experiences resonate far beyond their local areas - as such work is presented at international festivals, sent on tour, and made available through video and audio recording. A collaborative work between a choreographer from Chennai and a modern dancer from Pittsburgh imprints itself on the mind of a dancer in Hyderabad; an interaction between a jazz guitarist and a ghatam player in London inspires a composer in Indianapolis. While there are still those who cavil at such hybridisation, the trend itself can only grow because in the end it reflects a cultural reality that is more pervasive - and persuasive - than any negative valuation of it. Members of the Indian Diaspora today include many young people who feel like hybrids. Brought up in a non-Indian society, which highlights their ‘foreign-ness' they often revel in this dual identity. Britain's Akram Khan, for example, so successfully fuses a traditional form like Kathak with modern dance that his work is celebrated by the British government as being expressive of contemporary Britain. In the past an Indian had to choose between ‘traditional' and ‘modern', ‘immigrant' and ‘fully vested member of a society'. Today he or she can lay claim to both aspects of such dichotomies. In keeping with the socio-economic tenor of our times, the performing arts in the Diaspora are not solely dependant on government patronage either. Musicians have for quite some time been supported by recording contracts and concert fees. Now, as members of the Diaspora grow more affluent, they themselves fund non-profit organisations to promote Indian performing arts. Tours of Indian artists are more often than not organised by Indian entrepreneurs who depend on ticket sales within the Indian community. Offerings include recitals by south Indian musicians, hit plays from Bombay and blockbuster shows featuring Indian film stars. As Indians enter the field of production, presentation, and patronage, they choose what aspects of Indian culture get disseminated and begin to have a hand in effecting the larger society's image of what it means to be ‘Indian'. For years, within the mainstream of western performing arts, India and things Indian were represented by choreographers, composers, playwrights and even performers who were not Indian. The music for a play like Phaedra Britannica set in India was written by an American; costumes for the Mahabharata, though inspired by Indian dress, were designed by an Anglo-Frenchwoman of Greek parentage. There were few professionals of Indian origin in theatre, music, or dance, in the same way that society at large contained a relatively insignificant number of Indians. Even when immigrant populations in the UK grew, they rarely attended performances; their children were by and large not encouraged to enter the field.   When someone of Indian origin was successful in the performing arts, ‘Indian-ness' was seen to be incidental to his or her artistry, and only highlighted by other Indians, proud of such mainstream success. Zubin Mehta was first and foremost a leading conductor; only secondarily was he associated with - or representative of - India or things Indian. Even today, artists like the stellar counter-tenor Bejun Mehta, trained and brought up in North Carolina, are hardly thought of as ‘Indian'. While this is in keeping with a general tendency towards ‘colour-blindness' in the western performing arts, one which encourages directors and producers to give Indian artists non-specifically Indian roles - those of doctors or scientists, or even ‘Romeo' - it also means that images of ‘the Indian' gain no contours from such casting. When people of Indian parentage design sets or costumes for the theatre or opera, they rarely look to India for inspiration, even in a milieu where it seemed for a while that the only costume choice for men was some version of the sherwani or kurta pyjama - in productions which ranged from a British Richard II to an American Salome (the opera). Things Indian are instead, part of an international grab-bag that can be turned to even if the production itself makes no reference to India. Their use in, say, film scores, pop music, or dance choreography dilutes, rather than highlights, their specific ‘Indian-ness'. On the other hand, when Indians are among those who produce and make artistic choices, they can begin to effect changes in the general public's perception of themselves. In a recent New York production of Tom Stoppard's Indian Ink by a South Asian company, India and Indians were represented by people familiar with the subtleties of the Indian context. Brought alive by an Indian director with an understanding of multi-layered Indian society, the play became textured. Even minor characters were three-dimensional. Thus the audience could identify with them and with their preoccupations - even if many of those were culturally specific. With the growth of the Indian Diaspora and consolidation of South Asian immigrant groups there are now several companies run by people of Indian origin whose efforts are changing the picture of what is ‘Indian' in the performing arts - particularly when their work becomes part of the mainstream. Groups in England are invited to bring their productions - a Cyrano starring a well-known actor from India, a musical Ramayana from Birmingham, a modern play by an Indian playwright - to London's National Theatre. The success of such ventures, and of Indian popular culture abroad, leads to investment in expensive productions like Bombay Dreams which, even if it belongs to a western genre, employs Indian artists - composer, co-choreographer, script-writer, and most of the performers. The upcoming musical version of Monsoon Wedding is to be directed by Mira Nair herself.   There is also - however slow - an emergence and growth in the numbers of Indian comedians, of Indian playwrights, modern dance choreographers and performance artists. Their ‘stories' can be about being brought up Indian in a non-Indian world - about a mother who plies you with chicken tikka masala while urging you to marry a fellow Indian, or a boss who can't pronounce your name let alone the name of the village you were born in. Or they may deal with recently formed cultural stereotypes as when Keith Khan and Ali Zaidi of the English company Moti Roti collaborate with an American director on the multimedia show, Alladeen, to tell the story of call operators in Bangalore. Despite all this, South Asian artists in Britain and America will tell you that there is still a long way to go. Many are uncomfortable that images of what is Indian are still being decided by non-Indians. The poster for the Broadway Bombay Dreams, for example, features two young Indian models and not the actual stars of the show. Is this, they ask, because the two leads are considered talented enough to be flown to England to sing for the Queen, but aren't thought to look ‘right' enough to sell the show? Others would like to be free of labels and join the larger community of performers, have access to the larger body of work being done. For the moment, however, the kinds of successes mentioned earlier are heady. They encourage more and more people to seek a career in the performance arts, which in turn, leads to further ventures. Dance companies are being formed every year and recording albums being pressed. At this very moment in London a sitar concerto is being written. In Burbank California a TV sitcom centred round a South Asian family is being cast.

Photo: Ken Van Sickle Trained since childhood in classical Indian dance and music, Rajika Puri's Bharatanatyam guru was Sikkil Guru Ramaswamy Pillai, her Odissi Gurukul is that of Deba Prasad Das. Rajika has also studied western music (the voice and piano), American Modern Dance (at the Graham & Cunningham studios in New York), and Flamenco. She lectures on relationships between Indian dance, and music, sculpture, mythology, poetry, and painting - illustrated with slides, story-telling, and excerpts from dances. One of her current project involves developing music that interweaves Carnatic music with flamenco, in furtherance of the Flamenco Natyam venture. |