|

|

|

|

Smitha Rajan - A Journey in Mohiniyattam.... by Anu Chellappa, St. Louis, MO e-mail: anuchellappa@yahoo.com January 23, 2004 Smitha Rajan talks to Anu Chellappa about her grandparents, her mother and her art.

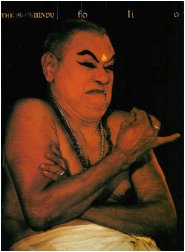

Kalamandalam Krishnan Nair and Kalamandalam Kalyanikuttiamma, Smitha's grandparents Anu: Namaste! I know that you completed over a thousand stage performances before you turned 30, and were honored for this in Mumbai. Can you recall when your first performance was? When was the first time you learnt dance? Who taught you? Smitha Rajan (SR): I grew up in a joint family, in an environment filled with classical dance and music. My grandfather was like a huge banyan tree, providing a majestic cultural backdrop for the whole family. My grandmother was this incredible person who had done so much research and work to bring Mohiniyattam to a good stature. Looking back, I feel it was truly in a "kala-aalayam" (a temple of arts!) that I grew up in!). My grandparents named their dance school "Kerala Kalalayam". I learnt the adavus and several items simply by observing senior students of my grandmother Kalamandalam Kalyanikuttiamma, my mother Sreedevi Rajan and my aunt Kala Vijayan. I felt as if Mohiniyattam was my mother-tongue - I felt it came naturally to me!

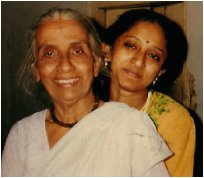

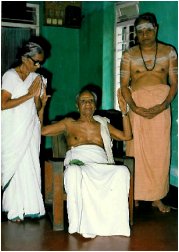

Young Smitha assisting her grandmother at a lecture-demonstration The first time I went on stage for a performance was in a nearby temple in Tripunithura, near my grandparents' house. I was 5 years old. I presented items in Bharatanatyam. The next year was my first professional performance in Mohiniyattam, when I was just 6! I remember vividly, presenting a Shankarabharanam varnam. At the end of the program, several people came backstage to congratulate me and I was so surprised to see so many people suddenly crowding around me, that I hurriedly looked for my mother or uncle, seeking to hide behind them!  I learnt Bharatanatyam from my aunt Kala Vijayan. I also learnt Mohiniyattam and Kuchipudi around the same time from the Kerala Kalalayam. My grandfather taught me Kathakali and fine-tuned my mukhaja abhinaya (facial expressions). He was a strict teacher and I used to be a bit scared to even sit in front of him! But he would always welcome any questions I had about choreography. In my teen-years, I started paying more attention to Mohiniyattam, under the watchful eyes of my mother Sreedevi Rajan. I was fortunate to have my grandmother and grandfather - at that time living legends in dance - fine-tune my dance in various aspects. Dance was a day-to-day experience - I used to rush back from school for dance class, or program or for a lecture-demonstration by my grandmother or grandfather... I was always more at my grandparents' house/dance institution than in my own parent's house!  Smitha's grandmother Anu: When did your grandmother first meet your grandfather? SR: My grandmother was going to start learning Mohiniyattam at the Kalamandalam - the institution that the great poet Vallathol had started for the revival and propagation of Kerala's art forms. On the day of her arrival, he had requested the resident Kathakali teacher, who was my grandfather, to present a short recital for the guest. He got ready for the program, and was surprised to find that the main guest was a young girl stepping into the dance school for the first time! He presented his "Poothana moksham" (which went on to become one of his most famous and sought-after pieces). My grandmother could not bear to watch the latter portion of this piece, as the dancer (my grandfather) depicted the upward journey of the jiva, right from the very toes of Poothana. She left before the item was over........... That was when they met for the first time!  Smitha with her grandmother Anu: How did your grandmother get so deeply involved with Mohiniyattam. SR: My grandmother had gone to Kalamandalam in search of some manuscripts for her M.A. in Sanskrit. Poet Vallathol suggested that she learn Mohiniyattam there (this was in 1937) knowing that she would be a serious student. She took this up and her initial days of training at the Kalamandalam were rigorous - starting at 3.30am, with warm up exercises, flexibility exercises, practice of eye movements, eye-brow movements, adavus...... The diet was very simple and in just a few months, from a plump young girl, she lost weight and became a beautiful young maiden! Because of such an intensive training every day, in less than a year, she was able to present an arangetram, with all the items taught in Kalamandalam. After her marriage with my grandfather, who was a very devoted student and teacher of Kathakali, my grandmother went on to teach and research about Mohiniyattam. She traveled to several temples in Kerala (Suchindram, Padmanabhapuram...), interviewed the Devadasis, traced the items they performed, and recorded them in her notes. It is amazing, the amount of work she did, considering she did not have a tape-recorder, video recorder or even a camera! From all this, she arrived at a set of adavus, and a repertoire, which she concluded should make up a complete set of items for Mohiniyattam. Adavus: (classified into four sections, based on the jathis) 1. Taganam 2.Jaganam 3.Dhaganam 4.Sammishram The repertoire is: 1. Cholkettu - as the name suggests, it's a collection of "chollu"s. 2. Jatiswaram - pure nritta (for a combination of jatis and swaras) 3. Varnam - an elaborate piece with both nritta and abhinaya 4. Padam (in place of padam, a "keerthanam" or an asthapadi is some times performed) 5. Thillana - pure nritta, typically longer than jatiswaram 6. Slokam - entirely bhakti oriented piece - it's a prayer... 7. Saptham - the final item in the repertoire - this item gives a lot of scope for the imagination of the dancer. Examples: Rama Saptham, Shiva Saptham. Much later, in fact, 21 years after she first set foot into Kalamandalam, poet Vallathol called for her and my grandfather. The two of them went to meet him - he was in his death-bed. He explained to her why he had asked to meet her - he felt that he had worked hard to propagate Kathakali as an art form; but not so for Mohiniyattam, and that he was entrusting that task to her. She was stunned, and asked if she would be able to take it up. He replied that he was confident that she could take up this great task of nurturing Mohiniyattam, and that she had to march on bravely. Her own focus and determination saw her working tirelessly for Mohiniyattam all her life. Also, the support she received from my grandfather was wonderful - he being a great dancer himself, was totally sensitive to her thirst for learning more and more about Mohiniyattam. Anu: Tell us about your mother. SR: My mother is an excellent dancer, a brilliant choreographer, a patient and kind teacher, a singer and even a poet! She is one of the best-kept secrets in the world of Mohiniyattam. In 1959-60, she participated in the All-India Inter-University Youth Festival and represented Kerala. She won the first place in Bharatanatyam. Unfortunately, she did not pursue a career as a professional dancer after her marriage. But she continued teaching and studying the theoretical aspects and history of Mohiniyattam. She was a teacher in the Cochin Refineries School, from where she retired in 1999. From that point onwards, she has plunged full-time into dance. She has had several students from all over the world - Radha Dutta, Priyadarshini Ghosh, Deepti Omcheri, Shyamala Surendran, to name a few. The dance school she runs is called Nrityakshetra, an offshoot of the "Kerala Kalalayam" that my grandparents started. She is a recipient of the senior fellowship from the Ministry of Human Resources for her works on Malayalam literature in Mohiniyattam. It was she who very early in my life, noticed my potential for Mohiniyattam and took serious efforts to groom me for this dance style. She is a wealth of knowledge in stage and theoretical science of Indian classical dances, which is very rare among contemporary teachers. Anu: Today we find several Mohiniyattam dancers from outside Kerala. In fact, one dancer even claims that Mohiniyattam was "languishing in Kerala" before she took over! It is apparent that once your grandmother entered Kalamandalam, she had pursued Mohiniyattam with perseverance and dedication. Such being the case, what is your reaction to these dancers from outside Kerala, particularly when they make such statements and try to take credit for nurturing a dance style that was already well on its way to revival and glory, the revival being started off by poet Vallathol (who founded the Kalamandalam and later personally entrusted the work on Mohiniyattam to your grandmother) SR: Mohiniyattam was definitely not dying or "languishing" in Kerala! I remember my grandmother telling one Mohiniyattam dancer from outside Kerala who began claiming that she was the one who rescued this dying art form, "You are a very good dancer, but you should come to Kerala and learn proper Mohiniyattam from a guru". The dancer started quoting only the first portion of this advice! Later, this dancer claimed she was a student of my grandmother, although she has not learnt even a single adavu from her! I have nothing against Mohiniyattam dancers from "outside Kerala" - it does not matter where a dancer is from, as long as they do not get so involved with their personal glory that they forget the art form itself! It is with sadness that I notice several contemporary Mohiniyattam dancers mention that they have learnt from my grandmother, although they have not! To user her name just for publicity is not a correct thing to do.  Anu: What about Ph.D. holders in Mohiniyattam? Do you feel that our dance is suited for academic pursuit? SR: Degrees - for dance and music - is something new to us. It is a westernized approach. Our classical art forms are quite difficult to fit into the western pattern of education, since our arts evolved for centuries, around the gurukula system, with emphasis on experience and total hands-on approach... In the gurukula system, with only a few students, the guru can pay attention to each individual student - each student has a different pace with which he/she can learn, and only the teacher can have a feel for this and teach accordingly. Also, the student, by helping the teacher with the newer students, re-learns her own lessons, and internalizes what has been taught. Degrees - I personally feel it's a very delicate task to accomplish with the current academic structure as seen in our schools and universities, which are surprisingly disconnected with reality with regards to the arts. The only benefit that such an attempt would bring is some packaging of theoretical aspects and sharpening of presentation skills. Content and artistic richness evolve with experience - dance, after all, is a performing art! Many institutions, which are trying to formalize this and present a "degree" for dance, also want their teachers to possess a degree. I wonder how many of our gurus have such a "degree"! I am quite certain they are not going to get any "Masters degree" holder or a "Ph.D." holder! We need to address the issue of gauging one's talent and experience in the frame of modern education. I heard from Shri Dhananjayan that in his institution "Bhaaskara" in Kerala, where he is offering a B.A. Degree (in music and dance), the government is not allowing him to appoint eligible teachers, as they want only degree holders. This is very sad. This issue has been there for a while - at least two generations, as far as I can remember. Some decades back, the Tripunithura R.L.V. Academy, which offers degree courses for the classical art forms of India, considered appointing my grandfather as the Kathakali teacher there, but had to resolve a major problem - and answer the question: "Does Krishnan Nair have the qualification to teach the degree level students of the college?" Such a great dancer, who created global appeal and brought recognition for Kathakali, faced this! Then Professor Joseph Mundassery, the visionary education minister stepped in, and asked: "If Krishnan Nair does not have the "qualification" to teach Kathakali, then who else has it?"! Dr. Balamuralikrishna was awarded an honorary doctorate degree. He did not attend classes, take down notes and write exams for music! He practiced and practiced and honed his art over years! We need a permanent solution for this problem. Our major issue is the lack of vision of our social leaders and academic planners. Anu: There are several misconceptions about Mohiniyattam. First, everyone thinks that it is "slow". If people watched your Shiva Saptham dance piece, they will definitely re-think! Calling the entire dance form itself slow would be like saying a kriti like "ksheera sagara shayana" is slow! The kriti is in devagandhari, and the way Thyagaraja has composed it, there is a certain speed that it can be sung in. For the song itself, that can only be the right speed. I recall a quotation by Pt Birju Maharaj, where he says, "Dance has to unfold with the grace of a tree giving out leaves, flowers and then tiny fruit. Nothing so beautiful can be done in haste." What is your response to this misconception that Mohiniyattam is "slow"? SR: Mohiniyattam is a dance form that emphasizes on grace, but that does not mean it should be slow or considered so. Recently, I happened to read an interview of Ms.Anita Ratnam, where she mentioned that: "Mohiniyattam is pure liquid grace like the floating ocean waves and the sandy beaches. However, I cannot watch Mohiniyattam for more than 30 minutes, since I find the beauty too overdone...." As a dancer who feels that Mohiniyattam is her very language, I felt really sad when I read that. If a language does not transmit some information, and does not communicate a message, we cannot blame the language itself! Perhaps it is the people who are handling it? If a medium withstands the test of time, then it has proven its worth. There is no point blaming the medium if the person handling it is not competent enough and does not have the depth to communicate effectively using that medium or language. I will be glad to take up any challenge to prove this point! I recall an incident - in the 80s, my grandmother had this challenge - to prove to one of the board members of Kalamandalam who thought that it would be very difficult to watch a two and half hour Mohiniyattam recital, that it would certainly not be difficult! Also, at the cost of my humility, I must share with you that I have never heard my audience telling me "The program was boring" or "the program was too long". (and I have completed well over a thousand stages now!). In the recent past, in a recital (Swathi Music and Dance festival, Kochi, Oct 2001), I went on to perform not one but two additional items - two more than what I had planned, because of the response from the crowd! Next day, a review in The Hindu" mentioned that it was amazing that the audience at Kochi, who normally leave by 8.30, stayed on until 9.30 for a Mohiniyattam program! I could say that an art lover who has not experienced that has not watched true Mohiniyattam!  Anu: Most people immediately assume that the Mohiniyattam dancer wears her hair in a tight bun on one side of the head. When I watched your performance, with your hairstyle in the regular way - with a long, single plait, I felt that this was better looking, since few people can carry off a tight-bun hairstyle with Úlan, especially for dance. Why do you have this hairstyle? SR: Yes, this is the major difference from Kalamandalam Kalyanikuttiamma's style of Mohiniyattam with most others. This change of hairstyle (tight "bun" on one side) came into practice in Kerala Kalamandalam in the 1960's. Before that they too were following the hairstyle I follow now. My grandmother protested against this new style at Kalamandalam strongly because of three reasons. The first one being: When she was a student at Kalamandalam, dancer Shanta Rao (Bharatanatyam dancer), who went there to take some classes in Mohiniyattam, brought out this same idea of tying the hair on the side like the ladies in Raja Ravi Varma's paintings. Both Vallathol and her Guru (Appekattu Krishna Panicker Asan) completely denied this and made her understand that this hairstyle is tied by the women in Thiruvithamkur palace and not by the common women in Kerala. And Mohiniyattam is a shastriya nrittam and it has its strict rules to be always followed by its practitioners like the other classical dance forms of India. The second reason: Nritta or dance is a kind of yoga and in yoga Pingala, Ida, and the Sushumna nerves of the human body has significance in achieving Moksha, the ultimate peace. To represent these nerves a dancer plaits her hair by parting it into three, like three serpents crawling on each other (like the nerves itself), which start from the Mooladhara, bottom part of the spinal cord, and reach the Sahasrarapadma and then when it reaches the Bhrumadhya rekha (between the eyebrows) one attains tranquility. To represent the Sahasrarapadma we tie a bun on the back of our head and decorate it with flowers and to represent the Pingala and Ida nerves we wear the Suryakkala and the Chandrakkala on either side of the head. And the third is the symmetry: a dancer has to have this - which is very necessary and which you can see in most of the other classical dance forms of India. Kalamandalam Kalyanikuttiammas's book on Mohiniyattam explains this clearly. The book stands tall as the encyclopedia of this art form on its historical background and structural elaborations. Since it is written in Malayalam very few might have come across this work outside of the language boundary. I am right now working on translating her book into English.  Anu: You adhere strictly to tradition. What is your response to people who experiment with tradition? SR: I believe in the classical heritage of classical dance style, which evolved through ages and brought structures and traditions to it. I have tremendous respect and responsibility towards these. Every experiment will have its merits and demerits. What I see mostly is more of cosmetic oriented experiments than content oriented experiments. And some I would say, shouldn't have happened, because it gives some critics and observers a different impression of Mohiniyattam as a whole. When you dilute the core structure and traditional content of classical art form it can easily drift away from the level of true classical art form. I consider my commitment to its rich traditions and structure as my responsibility to do justice to this dance style, which was brought back to its grace and elegance by the life long effort of my grandmother.  Anu: What have been your major works so far? SR: Sticking on to the core of Mohiniyattam and performing it itself was a challenge for me all through my career. Mohiniyattam is facing so many problems - there are not many quality performers today. It needs more brand ambassadors than the current few performers. I have presented numerous recitals in India and all over the world. Most of my recitals outside India used to be the first time a Mohiniyattam program was presented in that city/stage. That was always a bit difficult, since the crowd had no idea as to what they were going to watch and many times I have felt that this would have been the same experience my grandfather might have faced when he traveled all around the world with Kathakali. Anu: Do you feel that "abhinaya" can be taught? SR: Yes! We all have it within us - but it needs training and practice to be able to bring this out in an effective way, to communicate this to an audience, to bring out the intensity on stage. As a teacher, I have worked with students to bring out their abhinaya and if the student puts in effort, I have definitely observed a steady improvement in their abhinaya. Anu: If there is one quality you would like to assimilate from your grandmother, what would it be? SR: Her determination. Anu: From your grandfather? SR: His hard work.  Smitha's grandparents with Mani Madhava Chakyar My grandparents' successes stand for the testimony of their support to each other. They never thought about fame and publicity - rather they had put utmost work and devotion to their art forms, which you can see very rarely nowadays. The kind of peer pressure the dancing world is putting on each other and the desire for fame and the kind of back door marketing which is right now so prevalent make you disillusioned and confused in an environment like this. For me, my grandparents' life is always my guiding spirit in my career.   Anuradha Chellappa was earlier a Bharatanatyam student of Malathy Thotadri and Usha Raghavan of "Kala Sagara", Chennai. She also learnt Carnatic vocal from Savithri Satyamurti, Chennai. She started learning Mohiniyattam from Smitha Rajan when she moved to St. Louis. Anu currently works as an Oracle DBA; she has degrees in Physics, in Vaishnavism (from the University of Madras) and in Computing and information systems. Apart from dance and music, her interests include learning Samskritam, reading, hiking, step aerobics and inline skating. Note: Her mother Padma Chellappa, in Chennai, knows the entire Bhagavad Gita by heart and welcomes any person (children included!) who would like to learn the recitation of the Gita. Contact: (91- 44) - 24354334, email: padmachellappa@yahoo.com. |