Narthaki

News

Info

Featured

|   |

e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com Twin yarns of empowered Eves February 27, 2017 In Puranic annals, there are two epochal encounters that are clear triumphs of the feminist among our ancient story-tellers. The first is the encounter between the deva-guru's son Kach and the demon-guru's daughter Devayani: when Kach, at the behest of his father Brahaspati, comes to learn from Sukra - the preceptor of demons – the mritasanjivani stotra (magical hymn of resurrecting from the dead), which the war weary gods are in dire need of. Besmirched by the beauteous Devayani, Kach manages to captivate her blossoming love, responding to his earnest pleadings of passion. This goes on till the resentful demons kill the aspiring Kach. Egged on by Devayani, Kach is revived from death-bed by Sukra through an application of the very same hymn and an instant learner, Kach attempts to escape to the gods, armed with his new knowledge. Heaven knows no fury like the woman scorned and Devayani pulls herself to her full height, roundly condemning Kach to remain forever a mere carrier of knowledge, but never able to use it in practice. The second encounter was the one between Arjuna, the middle Pandava - during his years of remaining in penance as a mendicant recluse – and Chitrangada, the strapping young princess of Manipur, brought up as a fighter-warrior son-in-disguise by her doting father. Suddenly, taken in by the surging emotions of a damsel, she is aroused by Arjuna at the first sight of his immaculate masculinity. And equally suddenly, she finds herself grossly inadequate, facing rejection by the indifferent male, citing a vow of celibacy. A diffident Chitrangada moves the high heavens to secure Cupid's blessings for donning a transient seductive role. Arjuna succumbs, but after a year of consummate ardour, is inquisitive enough to seek the "real" Chitrangada. They agree to marry, but now on equal terms. Tagore, in his time, penned inimitably his long poem Viday Abhishap (The Parting Curse) and the dance-drama Chitrangada, based on these two mythic encounters to pass a clear message for women's empowerment and emancipation, much ahead of his time. In the poem, Devayani narrates clinically the willful stratagems adopted by Kach to seduce her for achieving his mission and, thoroughly humiliated, she pins him down to remain, all his life, a dejected carrier of useless information. In the 1935 dance drama, on the contrary, there are many hues and fragrances of a maiden's changing psyche and the ultimate unfaltering proclamation by a liberated woman. Kach'O'Devayani (as Viday Abhishap was renamed), presented sometime back by the Rabindra Bharati University alumni in Kolkata (and Baltimore), was an innovative visualization of the woman's spirited pronunciation on her partner, etched through all three extant forms of Chhau. Choreographed by Sharmila Banerjee, Devayani (essayed brilliantly by Shelly Paul) and her companions used the soft and genial style of Mayurbhanj Chhau, while Arjuna and his compatriots danced in the virile, simply masked Seraikela form exhibiting their heroics. Finally, the demons pranced around Sukra's hermitage in the fighting scene in Purulia Chhau idiom, colorfully masked and attired.

Kach'O'Devayani  Chitrangada

Chitrangada

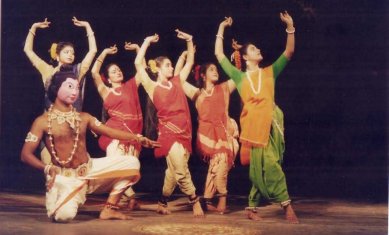

Chitrangada, presented recently in Kolkata by Darpan Dance

Akademi from Guwahati, was in contrast, a classical dance drama, blended

liberally with theatrical dialogue. Choreographed by Anjana Moyee

Saikia (who also danced with aplomb in the eponymous role) in a mix of

Manipuri, Odissi, Kathak and Sattriya styles, the play begins with a

vigorous thang-ta, the Manipuri martial arts, to depict a

cross-dressed Chitrangada and Sakhis being groomed to protect their

land. A hunting scene by the maidens follows with the song: The rumbling dark clouds thunder over the mountain peaks casting shadows on the deep woods...,

when they suddenly stumble on a resting Arjuna. The latter simply

ignores the event, but Chitrangada is deeply impressed by the majestic

Pandava. Rejected in her approach, the princess of Manipur feels quite

forlorn, invoking Nature: Oh the storms, do descend on the dried up branches and parched leaves of my life... The companions suggest seeking a boon from Kamadeva, the love deity, which she promptly does, in a gorgeously decorated backdrop prepared for the ardent worship. The story is quite different when she now accosts Arjuna: The dreamy intoxication is rushing through the body and mind.... And the hero is simply head over heels: The days of single suffering are over / All the roads now terminate in your pair of eyes... After a year-long dalliance, the satiated Arjuna is looking for a change and a new, self-assured Chitrangada asserts indubitably her femininity for an equal partnership. The curtains come down as Arjuna and Chitrangada sing in unison the concluding Sanskrit hymn: Let our eyes be honey laden, our limbs bearer of love, our hearts drawn close and our minds free of lust...  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |