|

|

|

|

|

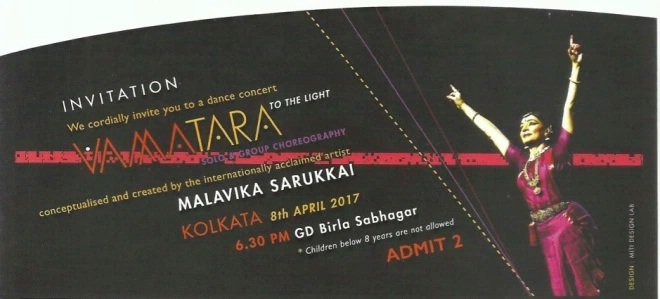

On watching Malavika Sarukkai's Vamatara: To the Light - Vikram Iyengar e-mail: iyengar.vikram@gmail.com April 23, 2017 If ever I was able to watch only one Bharatanatyam performer from the hundreds that exist, I would choose Malavika Sarukkai without batting an eyelid. Of course, after making that choice, the eyelid would bat crazily questioning why such a straitened situation existed at all. Similarly, soon after I began to breathe in the magic she created through primarily her own dancing in Vamatara: To the Light, niggling doubts began to assail me as to how to read the work and the professed content in our present-day scenario.  Malavika Sarukkai has a softness of touch that always imbues a sometimes tyrannically angular form like Bharatanatyam with a languorous grace and fluidity. This has always amazed me when I watch her dance. It is not necessarily her choreography: indeed, while the four others who performed in the group pieces with her were commendable dancers themselves, none brought in quite this quality to the body. To melt into movements of liquid sinuousness from sharply defined postures, and then un-melt too is an ability most dancers struggle to achieve. And to do that with seeming effortlessness and incredible musicality is part of the rich gift that Malavika Sarukkai offers us. All this I had gone to see, all this I had expected, as I had expected her to stick within the idiom of Bharatanatyam but bring a very personal and unique approach to recognisable content and communication. More than a decade ago I saw her Kashi Yatra - a solo interpretation of Damodhar Gupta's eighth century work, Kuttanimatham, detailing courtesan Varastri's life in Kashi. One brilliant image remains engraved in my mind: her slow, deliberate, marvelously detailed delineation of the courtesan's tryst with her beloved performed in a sharp spot up stage centre. Several such images imprinted themselves on my memory in Vamatara: the description of Krishna once again up stage centre, with every small gesture visible to us several metres away, the image of Meera imagining Krishna entering her 'heart' and a lotus blooming within - these are just a couple that come to mind. These are also moments when - to my mind - the lighting design worked to enhance and support the choreography. Otherwise, I found the design unnecessarily overbearing and intrusive, often clumsily calling attention to itself as a separate entity doing its own thing. A cinematographer recently told me: if you notice cinematography in a film separately, we have not done our job. Similarly here: a profusion of lights serving no very clear purpose except to create loudly dramatic un-nuanced atmospheres - quite opposed to the nuance the choreographer brings to her own dancing. The best-lit piece was the Meera bhajan, where the lighting - mercifully - did nothing very much at all. However, this is not a review or report on the production, but an examination of the niggling doubts I mentioned. Vamatara: To the Light is a series of four pieces inspired by the image of a lotus growing out of the sludge towards sunlight, air and life - a metaphor for hope, for new beginnings, and a symbol of purity and perfection in Hindu art. Almost every deity is described as seated on a lotus, being lotus-eyed, lotus-faced, lotus-footed, with a complexion of a blooming lotus… the similes are endless, and Indian classical dance is inundated with these references. Given Malavika Sarukkai's propensity towards re-engaging with classical dance symbolism, this was a rich reservoir for her. Indeed, I do feel she fell far short of the potential the image of the blooming lotus offers an artist of classical dance. Be that as it may, my doubts began with the opening announcements and they refused to be pushed away for the entire duration of the performance. I was sitting in a plush air-conditioned auditorium located (illegally by all reports) in the basement area of a white marbled Hindu temple dedicated to Lakshmi-Narayan and built by an industrialist family from north India. Only a few days ago Calcutta and the rest of Bengal had been subjected to aggressive weapon wielding processions supposedly celebrating Ram Navami (a festival that has never been part of the local culture). These processions had been organised and led by the Hindu nationalist political party that has recently swept the polls in Uttar Pradesh with communal polarisation as one of their barely disguised pre-poll campaign strategies. They are now flexing their muscles in West Bengal, a state they have never had a foothold in till recently. This same party had brought down the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in 1992 - an event that was preceded and succeeded in much of north and west India by similar weapon wielding activities in the name of poor Lord Ram. These events unleashed the bloody communal riots in Bombay in 1993. This political party is today under the leadership of a man under whose chief ministerial tenure Gujarat saw the genocide of Muslims in 2002. They are presently on an apparently unstoppable march across India, hailing every poll victory as the birth of a new, free, truly Indian nation. And this political party has a blooming lotus as its symbol. I was in a quandary. Here - on stage - was the blooming lotus being interpreted as a symbol of hope, of rising from the blackness of despair towards light, a sublimely positive metaphor imagined through dance by one of the foremost classical dance artists of our age. And there - outside (and perhaps insidiously inside too) was the same lotus being held up as a symbol of the very same things but with hard-core, right-wing, narrow-minded religious-nationalist sentiment as its driving force. What was I to do? Was I to respond to the art or to the politics? Can they really be such completely separate things? How disconnected can classical artists afford to be? Is classical dance to be presented and viewed only within a rarefied, isolationist ivory tower that takes no cognisance of anything else but itself? Conversely, are we to shy away from where our personal imaginations lead us as artists purely because of the reading they may have in prevailing socio-political circumstances? Is that not also an act of self-censorship, something that artists as a creed vociferously oppose - at least in word if not in deed? “Who is the classical dancer as a citizen of India?” This question was posed to me by a Bharatanatyam/contemporary dancer-choreographer from Chennai during a conversation just after a rather troubling conference presentation at the Ignite Festival of Contemporary Dance, Delhi, October 2016. The conference session comprised a panel of three classical dancers - Priyadarsini Govind, Justin McCarthy and Rekha Tandon - and attempted to address, not very successfully, changing pedagogical modes of transmission and the relevance of the guru-shishya parampara. Asked about if and how classical dance modes and processes could respond to current times, Priyadarsini Govind referred to one of her recent productions. It was inspired by an ancient Tamil text - a poem describing a soldier's mother. She hears that her son has been killed on the battlefield, but is devastated to also hear that he bears his wounds on his back indicating that he was fleeing. She rushes to the battlefield, maternal sorrow battling with hurt pride. She finds his body and discovers the wounds on the front, putting her fears to rest. The poem describes that moment as being the proudest moment for her as a mother - even more than the moment she had given birth to him. It is not for me to comment on how this poem was received in its time, nor what the poet intended. What left the conference audience stumped was Priyadarsini Govind's analysis of how this piece was relevant to today. Referring to the on-going agitation in Kashmir and violent clashes between the Indian army, locals, and separatist groups resulting in death, maiming (specifically through the army's use of pellet guns), and curfew, she made an astounding statement: all the (army) mothers who had lost their sons were feeling the same pride today, resonating with the emotions of the mother in the poem. This declaration was made with an earnest virtuousness that can only be born of wearing several pairs of rose-tinted glasses (blinkers?). It is problematic at so many levels that one does not know where to start. Do we talk about the stereotyping of mothers and soldiers? The glorification of (forced) sacrifice? The feudal subjugation of individuals before the idea of a nation? The glossing over of a state that turns against its own people? What is considered courageous? What is an act of patriotism and what is not? The list is endless. But I would rather step back and pinpoint the utter lack of nuance in this blunt statement that understands none of the complexities of modern-day India or the world, automatically harks back to ancient legacies when asked about contemporary relevance, and relates them most superficially to prevailing circumstances today.Sensitivity is multi-pronged: should not the artist's sensitivity and sensibility be informed - at least tangentially - by the world he or she inhabits? Should it not include at least an awareness of the context within which a work of art is presented and perceived? Truly, where do the (classical) artist and the citizen meet and overlap? Can one be an aware and responsible citizen AND be a classical artist simultaneously, or are they often at loggerheads? I have no idea about Malavika Sarukkai's personal political leanings or colours, or - indeed - whether she professes any at all. The latter possibility is, in itself, a worrying thought. If she truly espouses the cause of the blooming lotus party, then Vamatara could well be read as a piece of artistic propaganda, similar to Utpal Dutt's ground-breaking theatre productions in the 1950s and 1960s which made no bones about his leftist ideology. However, given my experience of the world of soft focus that classical dancers often inhabit, I very much fear that it is far more likely that the dancer here is wholly unaware of any such implications, caught completely within the isolating and sacrosanct view that classical dance can have of itself. This is symptomatic of classical dance and dancers, this absence of critical thought - of any need for critical thought - in how we connect to the world today, what we say in the world today. That is what makes it so easy for us to be used as ambassadors of invented, bowdlerised, unquestioned culture - the pall bearers of an imagined, unblemished Incredible India, of a falsely fabricated nation state sallying forth on sweepingly pseudo-emotional statements involving images of stoic mothers and heroic sons. In this indiscriminate, conveniently naive propagation of stereotypes and symbols, we fail to see that we become caricatures of ourselves serving a purpose that may not be our own. Malavika Sarukkai's closing group piece - Into the Light - embodied hope and human enlightenment in the figure of the blooming lotus arising out of the chaos and darkness of the present times. Once again invaded by the irritatingly intrusive and literal lighting design, the five dancers moved quite robotically to a soundscore suggestive of the turmoil of modern life. As the lotus arrived on the scene, the lighting design beamed with expectant happiness, the black stoles on the magenta costumes disappeared, and a sonorous Gayatri Mantra filled the air - why did that remind me of the ever-increasing competitive raucousness of religious music today, be it the azaan or the bhajan? I wondered what it would have been like if the choreographer had reversed the trajectory. What if the black stoles, the grating soundscore, the shadow-filled lighting design had appeared as the lotus bloomed? How would we read this inversion / subversion of symbolism, this dirtying of purity? That's the question which remains with me - for myself and for the droves of classical dancers in India and across the globe. Are we ready to dirty our hands with the potential our art offers us? Can we birth contaminated but resilient lotuses, soiled by our own experience but all the more precious and relevant for that? Or do we remain aloof, cut off, hermetically sealed in a static notion of tradition, and precariously pure - so pure that even our art cannot touch us? Vikram Iyengar is a dancer, choreographer, theatre director, performing arts researcher, writer, arts manager and curator based in Kolkata. He is co-founder of the Kathak-based performance company Ranan and initiator of The Pickle Factory - a proposed venue for dance and movement practice and discourse. In 2015, Vikram was awarded the Ustad Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar from the Sangeet Natak Akademi, Government of India for his work in contemporary dance. An ARThink South Asia Arts Management Fellow (2013-2014), he is currently Global Fellow of the International Society for the Performing Arts (2017). Comments Congratulations to Vikram Iyengar for bringing out the inner turmoil of classical dancers and exposing the fact that we classical dancers haven't still found a way to answer these questions....is the classical dancer a citizen or not and is he or she supposed to answer these questions or not.... I have a question though....do musicians get it easy....they never have to deal with their link with contemporary issues , or responsibilities towards contemporary issues.... So is it the art form or the artiste? Once again a wonderful article....so many points which have been disturbing me over the years as a classical dancer have been spoken so clearly. - Anon (April 29, 2017) Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |