|

|

|

|

Spaces for Engagement: art on a pavement (possibly) - Vikram Iyengar, Kolkata e-mail: info@rananindia.com November 17, 2011 (This article first appeared in e-Rang - an initiative of the India Theatre Forum - on 15 October 2011. Other e-Rang issues are available to read on theatreforum.in/erang/) During a recent trip to the UK, I encountered various examples of the relationship between artworks, the public domain and the rejuvenation of urban spaces. These experiences underlined several issues about how, why and where an engagement with the arts as a social concern is both possible and necessary. A space to learn, to play, to gather, to grow, to appreciate, to imagine ... and to have a whole load of fun. The artist community in the UK stands at critical crossroads today. They have just seen one of the biggest and most controversial funding cuts in the history of Government support for the arts - a move that will doubtless have repercussions the world over. Well-established performance companies - some of whom we have enjoyed and been inspired by in India - have had entire grants disappear. Others have been severely destabilised forcing entire re-envisioning of budgets, projects and indeed principles, while others still have ironically gained in stature and finances. Finding any evidence of a positive outlook in the midst of this gloom - let alone public and private investment in the arts - came as a surprise. I suppose it's the old question: is it a problem or is it an opportunity? Conversely, however, the examples I will refer to are not directly concerned with the performing arts - save the first one. So does the claiming of public space and imagination for the performing arts require a wholly different approach, or can we find some inspiration in the following instances?  Sculptures of local cartoon figures in Dundee City Centre Pic: Amlan Chaudhuri

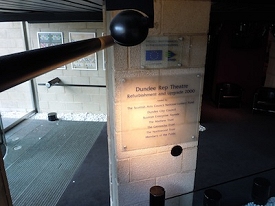

Dundee's industrial prominence in the 18th century was based on the whaling industry and linen mills. Later, the mills converted to jute production and the jute industry dominated the city from the latter part of the 19th century earning it the epithet 'the city of jute, jam and journalism' (jam - commercial marmalade production was pioneered here: journalism - the publishing firm DC Thomson and Co set up in 1905 still exists). The jute trade declined in the early 20th century due to reduction of demand and competition from the emerging jute industry in Calcutta. My very brief visit of only a few hours was primarily to the Dundee Repertory Theatre which houses Scotland's only full-time repertory ensemble, the Dundee Repertory Ensemble, and Scotland's national contemporary dance company, Scottish Dance Theatre. The first thing that caught my eye in the Dundee Rep foyer was a large plaque thanking public, individual and private donors for their support. This is perhaps no unusual occurrence in the UK, but it underlines the very special importance the Dundee Rep gives to an engagement with the community it is situated in. Such an engagement is rife with difficulties when one takes into account artistic considerations. Our host, Janet Smith - Artistic Director of SDT - often spoke about the balance they are asked to maintain between creating work perceived to be popular and work perceived to be experimental. That it does not have to be an either/or situation is something she has been trying to communicate for some time - with some success, it must be said. And it isn't only the Dundee Rep which invests in it's public. Across the road is the very new and modern Dundee Contemporary Arts building, an institution also committed to bringing art into public life.  The Dundee Rep pic: Amlan Chaudhuri  The plaque acknowledging donors in the Dundee Rep foyer pic: Amlan Chaudhuri

the new Liverpool Lime Street Station Pic: Amlan Chaudhuri Much of this has been facilitated through money that was pumped in for Liverpool as European Capital of Culture in 2008. That easily explains the transformation of the city centre with shopping arcades, cafes and restaurants and the imposing and refurbished Liverpool Lime Street Station (a rather dank station when I saw it last). Ironically, there are now fears about sustaining this posh commercial look due to the recession. But what there is no fear about - and what truly impressed me - is the entire waterfront. The whole area is dedicated to museums as excellent as they are varied. The Museum of Liverpool, the Maritime Museum, Tate Liverpool (with a special Magritte exhibition when I visited), the International Slavery Museum - and of course, you can't get away from a Beatles Museum as well! The sprawling area used to be the old Liverpool docks, and several of the old buildings have either been converted into museums or preserved. The museum that left the most indelible impression was the International Slavery Museum. Liverpool's prosperity has / had much to do with being one of the major ports for slave ships on the slave route between Africa and the Americas. It is only natural to wish away such a history. For a city to acknowledge the shameful part it played is a brave gesture: to do it through a world-class museum that documents and condemns without exception the history of the slave trade and actively builds awareness about and campaigns against similar human rights violations in the world we live in today, is unprecedented.  Liverpool Waterfront - Albert Dock pic: Amlan Chaudhuri  the new Museum of Liverpool on the waterfront pic: Amlan Chaudhuri  an old refurbished ship in front of the Maritime Museum pic: Amlan Chaudhuri I quote from the speech of Dr. David Flemming, Director National Museums, Liverpool, at the opening of the museum in 2007: It is needed, yes, to help illuminate one of the darker, more shameful and neglected areas in our history - an era in which this city played a pivotal role.

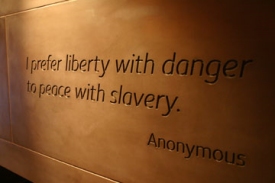

the Freedom and Enslavement Wall

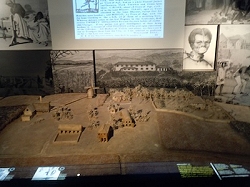

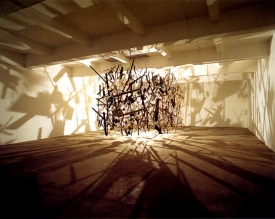

One enters the museum past the Freedom and Enslavement Wall. Peppered with quotations, the wall has several television screens with people - politicians, schoolchildren, historians, previous slaves... - sharing what freedom means to them. The history of the transatlantic slave trade is told through informative and disturbingly evocative exhibits. One film installation surrounds the viewer with the experience of slaves on a ship. Manacled limbs, vomit stained mouths, bodies cramped together, slivers of light through boards all edited together with the sounds of the rolling sea and cries of wretchedness. Add to that camerawork which simulates the heaving of the ships and one can barely last two minutes in the exhibit without feeling overwhelmed. Outside, you're quietly informed that it took six to eight weeks for such ships to cross the Atlantic. Sections dedicated to life in Africa before the slave trade, plantation life in the Americas, the American Civil War, the Ku Klux Clan, slave and anti-slavery literature, the legacies of the slave trade, racial stereotypes through everyday items and usage, slavery and human rights violations today are brought to life intelligently and creatively. Interactive models, performed readings of letters and personal documents bring the displays to life. There is the ironic letter from a European official who - in his zest to spare the labour of the natives in America - recommends that (and gives permission for) 500 Africans be transported to do the job; or the series of descriptions of plantation life by a guest from Europe complete with dinner table banter, the clinking of cutlery and political comments; and the clinical and heartless diary maintained by a plantation owner listing in graphic detail every sexual exploit with innumerable slave girls. Add to this a special Campaign Zone, curated temporary exhibitions, regular lectures and workshops, a detailed, informative and brilliantly laid out website with a network of links and you have an astonishing and holistically conceived engagement with history, culture and what it means to be human.  an African dwelling, pre-Slave trade pic: Amlan Chaudhuri  Artifacts from Africa pic: Amlan Chaudhuri  an exhibit on life in the American plantations pic: Amlan Chaudhuri From Liverpool to London and the Tate Modern - one of my favourite museums of contemporary art. Museums of art - especially contemporary art - can be threatening spaces for many, and often they fall into the trap of speaking only to a closed clique of artists and 'connoisseurs', quite forgetting the general public. The Tate Modern on the other hand expected 2 million visitors per year when they opened in 2000: the first year they received 5 million. I believe this has a lot to do with how the Tate museums all over Britain view their commitment to the arts, artists and audiences, and - specifically for the Tate Modern - a lot to do with the nature and spirit of the space itself. Located in the 'found' industrial space of the former Bankside Power Station, the amazing use of the space has always been a point of conversation. The architects and designers - Herzog & de Meuron - retained the grittiness, industrial feel and openness of the space, and also managed to infuse a surprising potential to house and enhance a range of artistic expression. From Anish Kapoor's massive Marsyas which swelled to fill the available space of the vast iconic Turbine Hall even forming the backdrop for concert performances, to Cornelia Parker's profoundly moving and silence-inducing Cold Dark Matter - the Tate Modern has consistently challenged both artists and audiences to re-imagine ways of creating, encountering and playing with art.  Cornelia Parker's 'Cold Dark Matter'

the Tate re-development design The Tate is currently undergoing a re-development to add a new 11-storey wing. The same architects who re-envisioned the original building have been called in for this project, and the space they are working towards "will redefine the museum for the twenty first century, placing artists and their art at its centre while fully integrating the display, learning and social functions of the museum, and strengthening links between the museum, its community and the City" (The Tate Modern Project website).    Views of Anish Kapoor's 'Marsyas' in the Tate Modern Turbine Hall I found a few things specifically exciting about the redevelopment: 1. It takes full account of the fact that "film, video, photography and performance have become more essential strands of artistic practice, and artists have embraced new technologies." I have so far spoken of particular institutions of art and culture engaging with the public by bringing them in. The Folkestone Triennial does the opposite: artists are invited to use the town as their 'canvas', utilising public spaces to create striking new pieces that reflect issues affecting both the town and the wider world.

a view of the Creative Quarter, Folkestone

pic: Victoria Long But Folkestone is also a town undergoing regeneration - a movement most visible in the Creative Quarter - a section of the old town comprising mostly of the narrow, winding and cobbled Old High Street. This area of the town is virtually owned and run by the Creative Foundation, "a charity launched in 2002 to regenerate Folkestone through the arts, the creative industries and education." The Foundation has bought up several of the old houses in the old town, renovated them and offers them at very reasonable rents to artists from all over Britain as places to live and work. There are precedents to this, of course. Hoxton in north London which assumed a trendy image as an artistic neighbourhood - an image which soon sent property prices skyrocketing and arts spaces away. And Portmeirion in north Wales - a tourist village wholly conceived and built by an artist inspired by Italian villages. The result I found to be cardboard false, self-satisfied and smug - not to mention ridiculously expensive.  A. K. Dolven's 'Out of Tune' on the beach at Folkestone pic: Victoria Long The Creative Foundation has so far not sent Folkestone the way of Hoxton or Portmeirion, but there are other problems. The Foundation has bought up property from those who could perhaps not afford to live there any more. But to see their family houses taken away and outsiders moving in at subsidised rents does nothing to appease the antagonism of the original owners. My friend - a director who had moved in to one of the lovely houses - had a shoe thrown at him by an old lady accompanied by a storm of verbal abuse. So while the UK's art world is gradually beginning to take positive notice of the Creative Quarter in Folkestone and specially the Triennial, the tensions within the town itself are yet to flatten out. It is too early to say which way it will go.  Paloma Varga Weisz's 'Rug People' at the derelict Orient Express terminus pic: Victoria Long The first instalment of the Triennial was in 2008. This second one comprises 19 specially commissioned sculptures, films and sound works for public spaces around Folkestone on the theme A Million Miles from Home. The pieces have been created for and installed in a variety of venues by artists from UK and elsewhere: Martin Creed's sound installation (which I found unsatisfying to say the least) plays as you travel up and down the old Folkestone Leas Lift run by water; A. K. Dolven's Out of Tune suspends a 16th century tenor bell 20m high on the beach and invites people to ring it; Camp's The Country of the Blind, and Other Stories is a film screened as a series of episodes at the National Coastwatch tower; Cornelia Parker's Folkestone Mermaid - the town's answer to the famous Copenhagen sculpture - has settled on a rocky outcrop on the beach; Paloma Varga Weisz's Rug People stands on the abandoned rail tracks at the dilapidated old train terminus of the Orient Express; Strange Cargo's plaques of local memories connected to particular town places - Everything Means Something To Someone - form an alternative and personal history to different spaces in Folkestone; and Hew Locke's beautiful and deeply moving For Those In Peril On The Sea is in the 13th century St. Mary and St. Eanswythe's Church - the oldest building in Folkestone.  Hew Locke's 'For Those In Peril On The Sea' pic: Victoria Long

Eight pieces from the 2008 Triennial were selected to remain and become permanent works of art. Eight more will have joined them by now from the 2011 pieces. So Folkestone will - over the years - become inhabited with more and more works of art that people can encounter and engage with in the most unexpected places and ways.  a teddy bear sculpture, one of Tracy Emin's 'Baby Things' pic: Victoria Long This is already evident. Tracy Emin's Baby Things (from 2008) - a collection of small sculptures like a shoe, a small glove or a teddy bear are scattered across town. Some are so small that they have to be pointed out - like the glove on spiked fence, which reveals itself as a sculpture only when you touch it. A tiny teddy bear sits under a railway bench on the Folkestone platform. The day I was leaving a little girl spotted it and ran up to it only to discover to her shock and delight that it wasn't the soft toy she had taken it for - all while an adult sat on the bench completely oblivious of its secret resident. At an international seminar on Public Art organised by the Goethe Institut, Calcutta in March 2010, a noted senior artist had contended that pieces of public art needed to be 'protected' from 'vandalism'. A younger artist had immediately offered a rebuttal, basically saying that once a piece of art is in the public domain, the artist must let go. It no longer is just about the work of art in itself, but how the public views and engages with it. In the same seminar, there was a presentation about Documenta 13 - a festival of commissioned public art similar to the Folkestone Triennial that takes place every five years in the small town of Kassel, Germany. One of the anecdotes related was about an artist who had created an installation of random objects outside a building in a public park. Soon the collection began to grow and change, as people added their own objects, and moved or removed others. Apparently, the artist was overjoyed! Once a year Calcutta gives itself over to a sumptuous celebration of public art - the incredible creativity of the Durga Puja in terms of pandals, idols, lighting, installations, performance and heaven knows what else. The flood of artistry and ideas range from the ridiculous to the sublime, but all are located squarely in the realm of an uncategorised public. Anyone can enjoy and interact with these expressions celebrating the annual homecoming of Durga - and indeed, everyone does.  children playing with Cornelia Parker's 'Folkestone Mermaid' pic: Victoria Long One of the images that will remain with me from Folkestone is that of two children clambering all over the Folkestone Mermaid gurgling with laughter lost in their own imaginary game. Their curiosity had been piqued, their imagination stirred, their perspective of their beach slightly altered ... and they were having a whole load of fun. I believe that their lifelong engagement with art has begun. Vikram Iyengar is a Kathak dancer, choreographer, theatre director and performing arts researcher based in Calcutta where he heads the performance company, Ranan. His recent visit to the UK was to work with Transport Theatre, Folkestone on the first phase of a performance project part funded by the British Council's 'Connections through Culture' programme. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |