|

|

|

|

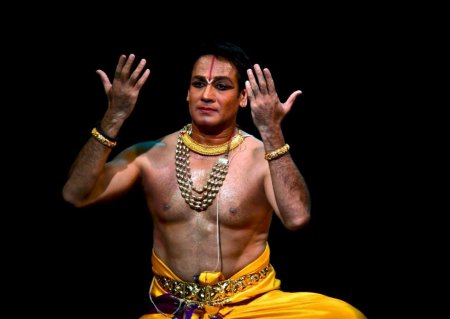

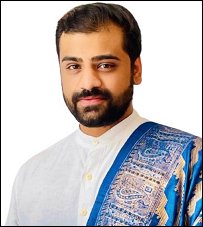

Sathya at 60: What endurance looks like in dance- Anurag Chauhane-mail: anuragchauhanoffice@gmail.com January 18, 2026 There are dancers whose journeys are marked by applause and immediacy, and there are others whose lives unfold like a raga at dawn, slowly, deliberately, revealing their beauty only to those willing to listen. Sathyanarayana Raju belongs to the latter tradition. His life in Bharatanatyam has never been about arrival. It has been about staying. Staying with the form through doubt and discipline, through neglect and renewal, through years when the art asked more of him than it gave back. As he turns sixty, Sathya stands not as a figure of nostalgia but as a living presence in Indian classical dance, one whose relevance has been earned through continuity rather than reinvention. His journey invites reflection on what it truly means to choose Bharatanatyam as a way of life, especially when that choice runs counter to expectation. Sathya did not grow up within a household steeped in dance. His introduction to Bharatanatyam came through a moment of fascination in childhood, a spark ignited by movement and rhythm that lingered long after. That early attraction matured into resolve, though the path ahead was anything but welcoming. At a time when Bharatanatyam was largely viewed as a feminine domain, a young boy aspiring to devote his life to it was met with uncertainty and resistance. The encouragement extended to him was measured, the doubts plentiful.  The reality of being a male Bharatanatyam dancer is rarely articulated but deeply felt. Opportunities are fewer, scrutiny sharper, appreciation uneven. There are moments when one's presence itself is questioned, when excellence is acknowledged quietly but rarely celebrated fully. Sathya lived these contradictions. He encountered phases where his work did not receive the recognition it deserved, when platforms were limited and acknowledgment hesitant. Yet he never attempted to compensate through exaggeration or rebellion. Instead, he chose immersion. He chose to let the form speak for him. His training was anchored in the discipline of the guru shishya parampara. Under the guidance of Subhadra Prabhu and later Guru Narmada of Shakuntala Nrityalaya, he learned that Bharatanatyam is not merely movement but thought, not merely expression but restraint. Every detail carried consequence. His parallel training in Kathak under gurus Maya Rao and Chitra Venugopal broadened his understanding of rhythm and narrative, lending his Bharatanatyam a muscular clarity and a refined sense of timing. Over time, Sathya's dancing acquired a quality that resisted categorisation. His nritta is firm and grounded, shaped by years of disciplined practice. His abhinaya is introspective, never indulgent, allowing emotion to surface through suggestion rather than display. He approaches choreography and repertoire with humility, returning repeatedly to traditional forms and complex compositions. His long engagement with the Ashtaragamalika Varnam reflects this philosophy. It is a work that has matured with him, absorbing the layers of a life lived in devotion to the art. Among his most defining artistic offerings is Ramakatha, a production that has become inseparable from his identity as a performer. Conceived and performed over many years, Ramakatha stands as one of Sathyanarayana Raju's most iconic works, not because of scale or spectacle, but because of its emotional and narrative depth. Within this single production, Sathya inhabits multiple characters, moving seamlessly from the devotion of Shabari to the wisdom of Jambavan, from the unwavering strength and surrender of Hanuman to the stillness and dignity of Rama himself. What makes Ramakatha remarkable is not merely the transformation of roles, but the inner shift that accompanies each character. Through subtle changes in stance, gaze, breath, and intention, he allows each presence to emerge fully, without haste or excess. Over the years, the production has evolved alongside him, deepening in resonance, becoming less a performance and more a lived meditation on dharma, devotion, and humanity. For audiences, Ramakatha remains one of the most enduring and beloved expressions of Sathya's artistry, a work that reveals the full emotional range of Bharatanatyam when guided by maturity and restraint.  As he performed across India and internationally, Sathya slowly created a space for himself that was unmistakably his own. In a field where male Bharatanatyam dancers remain few, his presence became quietly authoritative. He proved, without argument or assertion, that the form does not belong to a gender but to those who submit themselves to its discipline. Recognition came gradually, rooted in consistency rather than novelty. Teaching emerged as a natural extension of his philosophy. In 1996, he founded Samskruthi - The Temple of Art in Bangalore, envisioning it as a space where classical values could be transmitted with seriousness and care. As a guru, Sathya insists on patience, depth, and understanding. He prepares students not merely for the stage but for the long relationship they must build with the form. Through his teaching, he has shaped dancers who carry forward his belief that Bharatanatyam is not a career but a commitment. His contribution to the visibility of male dancers has been understated yet meaningful. By creating platforms such as Rasaabhinaya, an all-male classical dance festival, he addressed absence through presence. These initiatives did not seek to provoke but to affirm. They quietly reminded audiences that grace, strength, vulnerability, and devotion coexist within the male dancing body as naturally as they do within the female. Awards such as the Karnataka Kalashree have acknowledged his contribution, but Sathya has never allowed recognition to define his practice. At sixty, he chose introspection over spectacle. His Shasti Varna Chakra, a cycle of sixty performances, is not a celebration of endurance but an offering of gratitude. Returning again and again to the Ashtaragamalika Varnam, a piece his guru once insisted he internalise fully, he demonstrates that mastery in classical dance is not linear. It is circular, returning to the same work with a changed self. Watching Sathyanarayana Raju today, one senses a rare equilibrium. He stands as dancer, guru, and eternal student, all at once. His body carries the memory of years, his mind remains open to learning, and his art continues to evolve without abandoning its roots. In a landscape where great male Bharatanatyam dancers are few, his journey holds particular significance. Not because it is extraordinary in gesture, but because it is extraordinary in its quiet resolve. Sathya at sixty is not a retrospective. It is a living narrative of what it means to stay faithful to an art form even when it does not always return that faith easily. His life reminds us that the deepest contributions to classical dance are often made without noise, built through patience, humility, and an unshakeable belief in the power of practice. In celebrating him, we celebrate not just a dancer, but a way of being in Bharatanatyam that is increasingly rare and profoundly necessary.  Anurag Chauhan, an award-winning social worker and arts impresario, combines literature and philanthropy to inspire positive change. His impactful storytelling and cultural events enrich lives and communities. Post your comments Please provide your name along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name in the blog will also be featured in the site. |