|

|

|

|

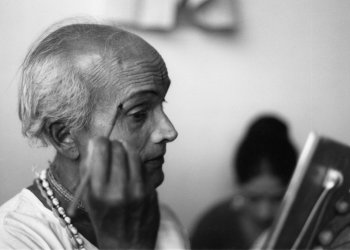

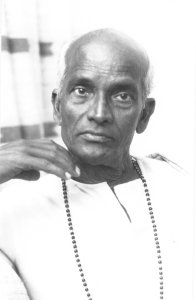

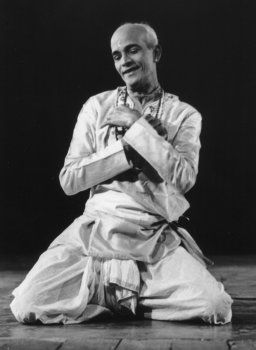

Guru Pankaj Charan Das: A Life - Timeless and Boundless - Sutapa Patnaik e-mail: sutapapatnaik@gmail.com January 21, 2014  (Photos used with this article are courtesy Mr. David J Capers from USA. He is the husband of well-known Odissi scholar and exponent Professor Dr. Ratna Roy. Dr. Roy is one of the prime disciples of Guru Pankaj Charan Das and an acknowledged authority on the style of the guru.) The role of Guru Pankaj Charan Das in the reawakening of Odisha's ancient dance tradition is both fundamental and dominant. Although he garnered uncontested recognition for his contribution to the art world, a lesser known fact of this avant-garde guru is his effort to bring about a transformation in the social attitude towards dance and dancers. Guru Pankaj rose valiantly from the ashes of the sacred convention - of offering music and dance as a service to the Almighty - that had been incinerated by its own effulgence; and he became the first among the earliest of those that helped revive Odissi in the 20th century. Standing tall in his own merit, he constantly lent himself to various interpretations of resurrection, from artistic impulses to social awareness.  By birth, Pankaj Charan belonged to the Mahari1 tradition, the only all-female service from among 36 listed rituals for the reigning deity of the Jagannath temple in Puri. Even as the little boy grew up in an environment of devotional music and temple dance, he was quick to recognize the social and economic shortness associated with his family. He realized early that his lineage2 would pose barriers to attaining basic social respectability as an individual. But, he was also aware that his identifiable descent allowed him access - though not entirely direct - to the closely guarded knowledge of music and dance meant for the Lord. Pankaj possessed a prodigious capacity to follow the nuances of the sacred dance, which he studied from his aunt Mahari Ratnaprabha. Since Mahari dance was confined to the women of the family, Pankaj faced tremendous opposition from the family to learn the devotional art. As a male member, he was only allowed to play the mardala (a traditional percussion instrument) in accompaniment to the Maharis' religious offering; but not the least to study the sacramental custom. Unyielding that he was, a trait that never failed to loosen its grip over Pankaj, he did not allow any of his life's circumstances to come in the way of his learning and disseminating the knowledge of the art. Around the same time that Pankaj made a mark as an artiste in school, he exhibited a lack of interest in formal education3. Instead, he found his calling in the acrobatic 'Gotipua' tradition at the local "akhada-ghara" (a specialized training centre for gymnastics, music and dance exclusively for men) and the "jatra" (the roving folk theatre of Odisha). This served to be a source of solace for Pankaj who was faced with a grim reality. Orphaned at a tender age, Pankaj was consumed with an elemental sense of responsibility towards his family's wellbeing. So, he became a vendor, sometimes selling "paan" (an indigenous preparation of betel leaf combined with areca nut and/or cured tobacco, often used as a mouth freshener) and at other times hawking small items like food and water in theatres. To augment his meager income, the young boy entertained people with imitation of songs and dances from movies, often till past midnight.  At a time when Pankaj was struggling to make ends meet, he joined theatre as a dancer and dance director. By then, he had begun to display with exemplary precision some esoteric dancing styles, including Bandha Nrutya (a kind of dance with complex poses and convoluted movements) and Thali Nrutya (a dance in which the performer balances himself on a brass plate called "thali" with his toes, while simultaneously rotating two smaller plates with his hands). While working in theatre, Pankaj choreographed small pieces of dance before and between the acts of a play. His understanding of theatre, coupled with the knowledge of Mahari and Gotipua dance traditions, subconsciously helped young Pankaj experiment with the dramatic aspect in dance. He enthusiastically put to use his creative sensibilities to compose the introductory and intermediate dance items. It is here that Guru Pankaj choreographed 'Bhasmasura' with a young lad (who grew up to be the legendary Odissi guru Kelucharan Mohapatra) as Shiva and the theatre company's prominent female lead Lakshmipriya Devi (who later married Kelucharan) as Mohini and himself as Bhasmasura. This was the first time the age-old temple ritual sworn to secrecy for centuries, and to which Pankaj was privy by virtue of his birth, was presented in public. Mahari dance, being only a devotional offering to the Lord, had more to do with expression than movements. So Pankaj customized the predominantly expressive dance to meet the requirements of theatre and used all three styles - soft, vigorous and theatric - to advantage, which provided a signature quality to his compositions. The occasion was historical in more ways than one: A dance abundantly influenced by the temple tradition was for the first time performed on a professional stage outside of the sacred premises. Kelucharan and Lakshmipriya became the first students of the Guru Pankaj Charan Das style of dance. Since the timing of the landmark event coincided with the devadasis facing a ban on performance of dance as a ritual in the temple, Lakshmipriya turned out to be the first woman Odissi dancer ever. The dance struck a chord with the audience, and the common people got to witness for the first time a beautiful dance form with an innate classicism attached to it. The pioneering effort of Guru Pankaj was greatly appreciated by the masses but he faced severe condemnation from many quarters, including family members, who believed that this act only sullied the sanctity of the ancient art. But he was unfazed by the criticism and worked in a way that few could comprehend. He rose in rebellion against any pretension. His background in the social and historical context seemed to overtake his regular life of a guru. Yet, he worked relentlessly on honing and preserving the art.  For Guru Pankaj, this was a road only half travelled. He brought upon himself the mammoth task of restoring the then elusive respectability dancers deserved. As a conscious effort he began teaching the remodeled art of dancing to girls from the elite class that was culturally inclined and had the courage to dismiss the prejudiced ideas attached to dancing and dancers at that point in time. He was not merely interested in reconstructing Odissi; he wanted a certain kind of reformation in the minds of people. He knew this was the only way that would serve to raise the bar of social conscience with regard to dance and dancers. An extraordinary dancer and a phenomenal choreographer, Guru Pankaj's style exhibited unparalleled grace and classy appeal. His creations reflect the genius of a visionary. With his creative wisdom, he took to the common people the idea that dance was indeed a revered art, and worthy of inclusion in the curriculum of University education. He taught at the Utkal Sangeet Mahavidyalaya (Odisha's premiere college of performing arts) in Bhubaneswar, where many of the present day gurus have been his students.  Guru Pankaj adopted a unique instructional method, which though disciplined, allowed his students a lot of creative freedom. But this much-ahead-of-time teaching style had a flip side, too. There was no uniformity in presentation of his compositions: With the creative liberty allowed to his students, most of them presented the guru's compositions with their own perception of the theme. Many of his students couldn't relate to the pedagogy, a reason only a few of them stand committed today to carry on the legacy of his distinctively rich and varied style. Guru Pankaj's mission for himself was to follow an awareness that the centuries old decadent custom of dance as a service to the Lord is brought to the common people; and more importantly, dancers are accorded the due honor they merit. The test of his success was to be ascertained through a social change which would bring unto him the respect that eluded him for most part of his life. On a closer look, one observes that the story of Guru Pankaj Charan Das is indeed entwined with not only the story of revival of Odissi dance, but with the narrative of post-independence social and cultural renaissance, an aspect that most certainly asks for more academic exploration. Footnotes 1 Mahari is the local name for the class of "devadasi" (female servitor of God) that was traditionally dedicated to the service of Lord Jagannath. 2Although Maharis were chaste virgins, originally meant to sing and dance for the Lord alone, they subsequently succumbed to the morally offensive demands of kings, landlords and some other powerful men who in return of the forced ignominy provided economic security to these women. Thus, the erosion of moral values external to Maharis became the cause for the downfall of the auspicious women. 3 He is said to have repeatedly failed his high school exams. A former student of Odissi dance from Odisha, Hyderabad-based Sutapa Patnaik quit her career as a journal editor with some Indian and American publications to focus fully on writing on Odissi. She has undertaken intensive research and documentation on Guru Pankaj Charan Das, the guru of gurus in Odissi dance. She has also been the Associate Editor of Odissi Annual, the year book on Odissi. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |