|   |

|   |

e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com Delving into Folk roots Photos courtesy: Avishek Ghosh April 5, 2018 The Mangal-Kāvya tradition of Bengal was an archetype of the synthesis between the Vedic and the popular folk culture of Eastern India. According to the experts, indigenous myths and legends inherited from Indo-Aryan cultures began to blend and crystallize around popular deities and semi-mythological figures in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. A new story of the creation of the universe evolved, as quite different from the Sanskrit tradition but with an unmistakable affinity with the creation hymns in Rigveda and the other eastern myths of creation. Manasamangal Kāvya was the oldest of the Mangal-Kāvya that narrates how the snake-goddess Manasa established her worship in Bengal by converting a worshipper of Shiva to her own worship. Manasa, a non-Aryan deity, had her worship prevalent in ancient Bengal. It is believed, in fact, that she came to Bengal with the Dravidians who worshipped her in the hope that she would protect them against snakes. Manasa was also known as Bisahari, Janguli and Padmavati.

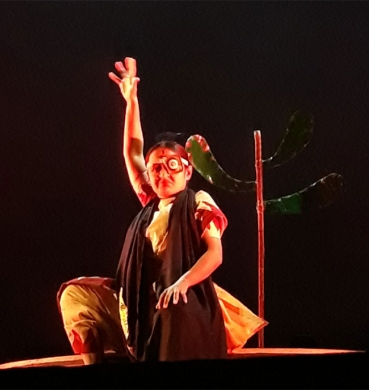

Chand Manasar Kissa (The Parable of Chand and Manasa), directed by Shubhasis Gangopadhyay and dramaturgy by Debesh Chattopadhyay, presented on March 25 by Kolkata’s well established theatre group Sansriti, followed faithfully the threads of the epic narrative, in delightful cameos of storytelling, song and dance. At the outset, Manasa was enacted with great verve by the veteran Monalisa. The story begins with the conflict of the merchant Chand Sadagar against Manasa and ends with Chand becoming an ardent devotee of Manasa. Chand is a worshipper of Shiva, but Manasa hopes to win over Chand to her worship. In collusion with her confidante Neta, the washerwoman (essayed with aplomb by Arpita Ghosh), Manasa lets loose many stratagems, to begin with, as a seductress and luring Chand to her bed. But, far from worshipping her, Chand refuses to even recognize her as a deity. Manasa takes revenge upon Chand by destroying seven of his ships at sea and killing his seven sons. The grieving Chand still refuses to capitulate. His flourishing trade comes to naught. When he and his wife Sanaka get their youngest son Lakhinder married to Behula, their full proof marriage parlour – made with iron shields -- has still a thread hole entry to allow a fatal snake bite by one of Manasa’s deadly minions. Behula, the new bride now widowed declines to accept this death and sets on a mythical voyage – with her husband’s corpse -- over full six months to the very threshold of heaven. Behula’s bewitching dance is held in a grand spectacle there and makes the gods bow to her abiding love for her husband, strength of character, indomitable courage and deep devotion. She succeeds in bringing Chand's seven sons back to life and rescuing their ships, before returning home with Lakhinder now restored to life. The captivating performance had three scoring points. First, it utilized the original verses of the folk play instead of a prose dialogue with great effect. Second, in lieu of built up sets, the play used the characters to group together forming imaginary large boats, colorful curtains to visualise marriage parlor, and a shadow play to create temporary illusions. Even the play’s flow of narrative was three-fold: by the dramatis personae, by an intervening sutradhara (a la classical plays) and by an intervening uncle-nephew duo who kept explaining the play’s contemporary significance. One only wished the last bit, especially the nephew’s sophisticated city accent and English words, could rather be avoided, leaving it to the viewers to reach their own inferences!

As seen above, Manasamangal, basically a tale of oppressed humanity, portrays the merchant Chand and his legendary daughter-in-law Behula as two strong and determined characters, at a time when ordinary human beings were subjugated and humiliated. The epic story brings out the caste divisions and the conflicts between Aryans and non-Aryans. The conflict between human beings and the goddess brings out the social discriminations of society, as well as the conflict between Aryans and non-Aryans. Shiva, whom Chand worshipped, was originally perhaps not an Aryan god but, over time, was elevated to that position. Manasa's victory over Chand suggests the victory of the indigenous or non-Aryan deity over the Aryan god. However, even Manasa is defeated by Behula. At one level, the poem suggests not only the victory of the non-Aryan deity over the Aryan god, but also the victory of the human spirit over the powerful goddess. At another level, Manasamangal is remarkable for its portrayal of Behula who epitomises the best in Indian womanhood, especially the Bengali woman's devotion to her husband. At yet a third level, the story heralds the rise of mercantile tradition and river borne trade among the burgeoning merchant class who would spread a new profession of business and commerce far and wide.  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |