|   |

|   |

e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com Rediscovering a scholarly legacy Photos courtesy: Mahagami February 15, 2018 Indian performing arts traditions are remarkably rich in scholarly treaties. Placed around the onset of Christian era, Bharata's Naṭya Shastra is probably the earliest known arts compendium in the world and notable as an ancient encyclopedic treatise that influenced dance, music and literary traditions in India. Its text comprised 36 chapters with a cumulative total of 6,000 poetic verses describing performing arts and inspired secondary literature of Sanskrit Bhashyas (reviews and commentaries), as compiled by Abhinava Gupta in the 10th century and by Nandideva in the 10-11th century. Nandikeshvara, regarded by many as a rival of Bharata, was the author of Abhinaya Darpana (The Mirror of Gestures) in the 2nd century, used often as a reference text for both Bharatanatyam and Kathak today. Matanga's Brihaddeshi, pertaining to Indian classical music and written in 6th-8th centuries, was the first treatise that spoke directly of the raga and distinguished the classical (margi) and the folk (desi). It also introduced Sargam notation, discussing musical scales and micro-tonal intervals, as clarifications of Natya Shastra on which its author had based his work. In that illustrious sequence of performing arts texts can be added Sarangadeva's Sangeet Ratnakara written in the 13th century as one of the definitive treatises for both Hindustani and Carnatic music. Known as Saptadhyayi (divided into seven chapters), its first six chapters Svaragatadhyaya, Ragavivekadhyaya, Prakirnakadhyaya, Prabandhadhyaya, Taladhyaya and Vadyadhyaya are concerned with various aspects of music and musical instruments, while the last chapter Nartanadhyaya deals with dance. The medieval era text is one of the most complete historical Indian reference points on the structure, technique and reasoning on music theory that has survived into the modern era. Indeed, many hold Sangeet Ratnakara to be the last common text for Hindustani and Carnatic systems of music before they had bifurcated. Sarangadeva was a Kashmiri Brahmin, who had come down to work for a Yadava king with capital in Devagiri (now Daulatabad, Aurangabad). Sarangadeva Samaroh, a major mainstream dance and music festival - together with the morning seminar - celebrates the glorious cultural past of the region over the past eight years, catering to 5,000 rasikas and some 500 music and dance aspirants in Aurangabad every year. Held under the aegis of Mahagami, the festival highlights performance of renowned artists as well as presentation by art-scholars: with focus on Sangeet Ratnakara and other ancient texts, while the morning sessions present fruits of research and lecture-demonstrations on academic aspects of dance and music. Sarangadeva Samaroh and Sarangadeva Prasanga, the ninth in the series spanning 19-22 January 2018 was a most pleasurable aesthetic experience. In the morning of day one, after the invocatory Vedic chants and the ceremonial lamp-lighting, Parwati Dutta, director and guru of Mahagami, gave a comprehensive video-based overview of the past eight festivals. Judging by the glitterati from the performance world who had participated in the past and blessed the festivals, one could easily sense how Mahagami was most definitely going places. This was followed by an insightful Vaadya Samanvayam, presented by P. Nandakumar and group from Irinjalakunda, Kerala. Beginning with mizhavu, the sonorous percussion instruments from Kerala were introduced and their mnemonics played, one by one: the two-faced chhenda, the vigorous maddalam, the musical edakka, the rare small drum thimila and the ubiquitous large cymbals. The musical scale and the complete song played on edakka came as a revelation.  Parwati Dutta  P. Nandakumar and group  Marga Natya  Piyal Bhattacharya

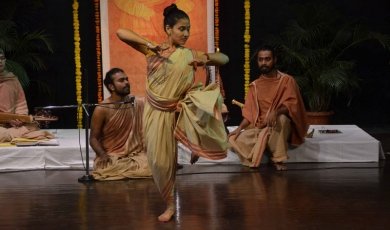

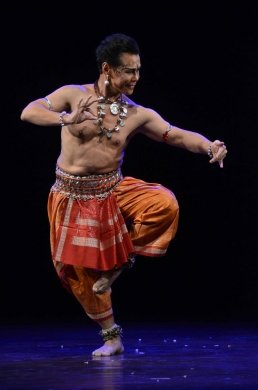

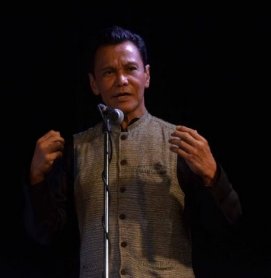

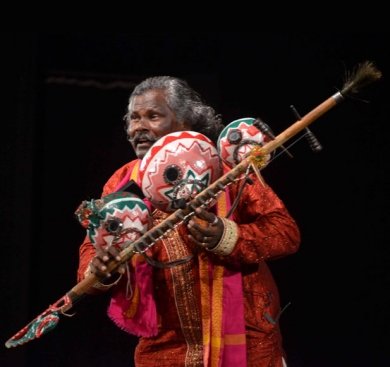

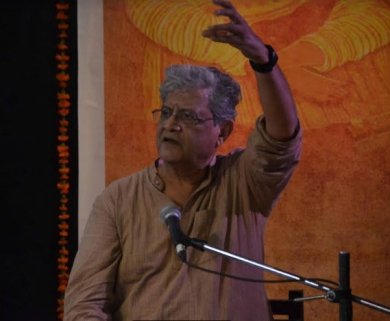

The evening performance of Pancha Vadyam by the Kerala group was a most disciplined affair playing Kerala's traditional rhythms, with one instrument dominating and others playing the second fiddle, tempo increasing from vilambit, madhya to drut and back to allegro, and the entire orchestration rising to a tumultuous crescendo. Marga Natya by Piyal Bhattacharya and group from Kolkata, took the stage next and unfolded an amazing re-construction from Bharata's Natya Shastra. First, Chitra Purvaranga was enacted, preceding Bhanaka, the traditional natya of Bharata. This consisted of Nirgeeta Vidhi followed by Asarita-Vardhamana Vidhi, according to specified rituals meant for the stage. Then entered the Sutradhar, almost a transgender in appearance and attire, whose dialogue introduced the dancers in sparse costumes, in the manifestation of bhavabhinaya, and not rasabhinaya. The dialogue was interspersed with vocal singing and playing of an ancient form of veena, while the dance was very sinuous. The morning on day 2 took forward the discourse on Marga Natya, with very articulate disciples of Piyal (who had left the city previous evening), making the viewers admire their complete grooming. In particular, Shayak (Sutradhar) and Pinky (the principal dancer) explained eloquently how the musical instruments - mentioned in Natya Shastra - were honed by them and their playing methods painstakingly re-formulated, how the sinewy dance postures were re-mapped from the temple sculptures, and how the musical swaras were linked with the yogic perceptions, from Kula-Kundalini in the navel to Sahasra-Dhara in the head. After a fascinating discussion-cum-demonstration, Dr. Karuna Vijayendra, dance scholar from Bengaluru, took over to dilate upon 'Lasyanga in medieval Karnataka sculpture'. She opened a new dimension for the studies on the famous Badami Shiva, based on the 6th century dance sculptures and decoded them on the basis of Natya Shastra. Her recent sculpture linked work established the Patra nomenclature of the female dancers: Alaya Vidushi (for temple-dancers), Asthana Nartaki (for palace-dancers) and Sabha Nartaki (for court-dancers), making her challenge the colonial nomenclature of 'Devadasi', though ascribed to the Chola kings' inscriptions in Tamil Nadu in the 10-11th century.  Disciples of Piyal  Ravanhattha Ensemble  Ramli Ibrahim  Dr. Karuna Vijayendra The evening brought in Jhumko performance by Ravanhattha Ensemble from Bhakarasani, Rajasthan. Arranged by Dr. Suneera Kasliwal Vyas, the cohesive group of 7 Ravanhattha artists began with an invocation to their folk deity 'Pabuji', but surprisingly without the Pabuji Padh before which it is invariably performed in the state. Accompanied by a small daphni and high pitched melodious singing, this was followed by the well-known Rajasthani folk-lyric Padharo mare desh...,in raga Madh. Another folk libretto Gorbandh came next, describing the rites of decorating camels. The recital concluded with a popular ditty about a bride demanding Ghararas and jewels. The evening's principal attraction was Datuk Ramli Ibrahim's (from Malaysia) solo repertoire composed by the early Odissi guru Debaprasad Das. Opening with a Mangalacharan emphasizing Sabdasvarapata, characteristic of his gharana, he elaborated a picturesque Odissi Pallavi and then switched over to an elaborate abhinaya piece on Ashta Shambhu finishing with Moksha. The morning on day 3 opened with a discussion by the researcher-musicologist, Dr. Indrani Chakravarti from Puttaparthi on an extremely rare folk instrument, Kinnari Veena, which she had literally 'discovered' among the 'Madiga' community living in Andhra and Telangana. The community's original appellation was 'Matanga' - the same as Matanga of Brihaddeshi. This sage had been credited as inventor of this archaic instrument, known since the Vedic period and fully described in Sarangadeva's Sangeet Ratnakara. The community plays as well as prepares the veena at home, as was demonstrated by dismantling and re-making one of the instruments in full view of the audience. Next to follow was an erudite discourse on 'the Odissi legacy of Guru Debaprasad Das' by Ramli Ibrahim, who forcefully brought out how his guru assimilated the usual asymmetric tribhangi of Odissi with his characteristic symmetric postures of the limbs and the torso. Ramli also explained his guru's predominantly male disciples leading him to develop tandava elements and also his penchant for Tantric elements in his compositions. The morning concluded with a fascinating discussion on how Ravanhattha, despite its existence even a millennium ago, did not find its entry into the temples and courts as it was more popular as a folk instrument. As a bow instrument, it is a great favourite in Rajasthan and its neighboring states, and definitely the precursor of modern sarangi. It came out how the design and playing of Ravanhattha have remained unchanged over the past 600 years and how it has gradually acquired ritualistic connections.  Dr. Indrani Chakravarti & Darshanam Mogulaiah  Ramli Ibrahim  Darshanam Mogulaiah on Kinnari Veena  Parwati Dutta The evening performance by Darshanam Mogulaiah on Kinnari Veena comprised an energetic playing of the instrument and was accompanied by a true-to-the-soil anecdote of how the newly married man tarries the demand for jewellery and toiletry from the bride, urging that he would have better varieties from the town for her. It was saddening for the spectators to be told later that the talented singer-cum-instrumentalist was today literally a beggar without any livelihood and his son has decided against following the father's profession. Parwati then took the stage with a spirited performance of Dhrupadi Kathak, with the young singer Chintan supporting her with the sombre raga Shree. Apparently, Dhrupad Nritya flourished in Gwalior in the 15th century during the reign of Mansingh Tomar, who developed a dance form combining the Desi and Suddha, i.e., the Shastric details and the regional flavour. Based on her research, Parwati explored light in relation to the moving body and the implication of melodic ambience, with copious reference to Kathak of the medieval period - as 'Pada Prabandhas' - with Dhrupad in temples as well as royal courts in the 14-18th century. The evening ended with Pt. Satyasheel Deshpande from Pune, singing Khayal in the old style. A senior disciple of Pt. Kumar Gandharva, he rendered short Aalaps and densely-worded compositions, which included raga Bhatihar and Komal Bageshri. The last morning on day 4 began with a most illuminating exploration by Parwati of lasyanga, mentioned by Sarangadeva, through Odissi and Kathak demonstrations by her talented students Sheetal and Shriya respectively. As brought out by her, Sangeet Ratnakara had elaborated as many as ten distinctive lasyangas - - in the movements of the head and the torso - that were not seen much in Bharatanatyam, but found elaborated in the medieval Kathak and Odissi. Pt. Satyasheel Deshpande followed next on 'Evolution of Khayal' and confirmed that the early Khayals were indeed quite wordy and showed remarkable preference for a few select ragas. He also confirmed the commonly perceived fact that raga Puriya has ceased to exist independently and is sung today only in conjunction with raga Dhanashri. The finale was chalked out by a most entertaining delineation of 'Parampara, Shastra and Prayog' by the poet-aesthete Ashok Vajpeyi - credited with institution building like Bhopal's Bharat Bhavan - - who interspersed his discourse with hilarious illustrations. According to him, there are huge varieties of Parampara which continue to exist regardless of Shastras; the latter tend to be self perpetuating, although intrinsically they are time bound, and at the end of the day, it is Prayog which is the flag bearer of both Parampara and Shastras, and not the other way round. He generally agreed to the audience perception that Prayog should cease to keep its foot perpetually on the back burner of age old myths and come round to embrace modern sensibilities - as has been done so vigorously by theatre, painting and cinema.  Pt. Satyasheel Deshpande  Ashok Vajpeyi Mahagami of Aurangabad deserves all praise for upholding the worthwhile exploration of theory and practice - consciously kept side by side - for nine long years and one can only wish them godspeed for many more years to come.  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |