|   |

|   |

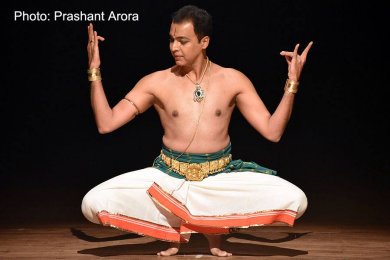

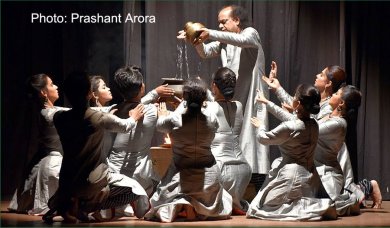

e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com A limitless lustre of love Photos: Prashant Arora April 22, 2017 It is not unusual among people the world over to perpetuate the memory of the dear departed, make efforts to compose tributes, build tombs and memorials, and initiate festivals in fond remembrance. Poets have composed countless odes to the deceased and even expressed yearnings to let them reappear just once more. Kadambari Devi, Tagore's sister-in-law and his childhood companion for long, was so close to the poet that in his lifelong creative oeuvre, the shadow of the beautiful lady always loomed large, her pensive eyes appeared in face after mysterious face in hundreds of paintings that he drew after some five decades since her unfortunate death by suicide, and his numerous letters and prose compositions carried a vision of pain and penance that he could never get over. It was not surprising, therefore, to find yet another artistic soul, Ashimbandhu Bhattacharjee, the noted Kathak exponent from Kolkata - who lost his mother about a year back - to have discovered the umbilical cord too dear to have been snapped so suddenly and needed a whole year to come to terms with the debilitating loss. Through this year he built an abstract theme named poignantly as Ananta - a lustrous garland of aesthetic grandeur that he wove to depict his own endless journey seeking his mother - and invited other artistes to share their thoughts and build their own memorabilia. Ananta, a two-day festival of classical dances presented by Upasana Centre of the Arts, Kolkata, was crafted as an open gesture on the topic of filial loss and love. On the first night, the veteran Kathak duo, Nirupama and Rajendra, began with an invocation to Shiva and switched over to Kalidasa's Raghuvamsha, in which the dancers recreated memorable events that Rama and Sita encountered, while on their journey back to Ayodhya by Pushpak Rath, after Sita had been rescued from Lanka. They concluded with Saath-saath, a duet composition with a blend of traditional Kathak and modern music, costumes and present day sensibilities.  Nirupama and Rajendra  Srimayee Vempati & Lakshmi Kuchipudi guru Vempati Chinna Satyam's daughter-in-law Srimayee Vempati appeared next with her 12-year-old talented daughter Lakshmi, in Ganesha Kouthwam, an invocatory item where the dancers offered salutation to Ganesha, a composition of Balamurali Krishna. Then came a lacklustre Radhika Krishna as an ashtapadi from Gita Govinda in ragamalika, where Krishna was portrayed as amour incarnate in the company of passionate milk-maidens. Their concluding item was Marakata Manimaya, dealing with madhura bhakti rich in musical grandeur, graceful diction, thrilling sollukettus and centering around the tale of Krishna, rounded off with Tarangam on brass plates, with precision of footwork in the rhythms writ large, as the mother-daughter duo executed highly innovative syllables. The finale was Nirvak: the Realm of the Unspoken, a masterly presentation by Manipuri dancer Bimbavati Devi. Indian mythology, no doubt, encompasses thoughtful people, enigmatic animals, talking trees and romancing rivers. But animals especially play a symbolic and significant role, and Nirvak delved deep into the powerful, silent world of animals, using the idiom of classical Manipuri dance, movements of Manipuri folk dance, thang ta (the martial art of Manipur) and motions of kartal cholom and pung cholom. In a picturesque sequence, there cascaded Matsya (fish), the first of the ten incarnations who saved the world from impending doom; Paramhamsa (swan), the great swan who magically separated the milk of knowledge from the watery dross of ignorance; Swarnamriga (golden deer) of Ramayana, representing gross human instincts of greed and illusion that lead to destruction of races and dynasties; and Mahasimha (majestic lion), so very gorgeous and gracious in its gait, uniquely chosen as the mount of Shakti, the goddess of indomitable courage and might.  Paramita Mitra The second evening was more germane to the festival theme, with the Kathak dancer, Paramita Mitra's overture with Nrityanubhuti, reminiscing on Ashimbandhu's mother, with an evocative Tagore lyric: Howsoever far I traverse in your limitless distance with my body and soul / there is neither death nor suffering nor separation ever perceived anywhere... She followed this with traditional Kathak on 11- beat rhythm and rounded up with abhinaya based on an imaginative composite of Thumri, Kajri and Dadra. The latter evoked sentiments of both Basakasajja (the gaudily attired) and Virahotkantitha (the sadly separated) nayikas and moved from the sprightly spring month of Chaitra (Don't you dare pull at my red wrap around...) to the monsoon downpour of Sravan (Will the incessant rains ever cease to let my lover come to me...).  Bimbavati Devi  Vaibhav Arekar The piece de resistance of the second evening - indeed, of the entire festival - was the Bharatanatyam veteran Vaibhav Arekar's visualisation of Tagore's long poem Debotar Grash (God's Fatal Curse). After an initial Nateshwara Shiva Stuti - in which picture perfect angika abhinaya sparkled, but sattvika was willfully suppressed - Vaibhav launched his magnum opus, in which the village headman had taken an eager widow for a holy dip in the turbulent sea, but also unwillingly carried her truant son even when there was no space in his sea-faring boat. The woman had made a vexatious vow to throw away her son into the sea, without realizing that her inadvertent words would be held against her when the waters, later, rose in a violent storm and the boat's load needed to be reduced for safety of all. While unveiling brilliantly the principal story, Vaibhav also explored, layer by layer - with intricate angika as well as exquisite sattvika - the baby shaping in the womb as embryo, the mother's fond bonding with the growing child, the playful boy's imagination running riot, and the mother's last, lost dream: with the son snatched away and instantly swallowed by the billowy waves. The grand finale was Ashimbandhu's choreography of Ananta that recreated the life of his mother, an otherwise ordinary householder, but an extraordinary woman and an excellent vocalist, who was denied her artistic debut by her near ones and the society at large. She, however, found both retribution and fulfillment through her dancer-son. The item captured quite well the struggle and the inherent protest of the wronged woman, without diluting the classical elegance of Kathak and did create moments of deep pathos and promise for Ashimbandhu as himself and Ranjani as his symbolic mother.

Ashimbandhu and group

Extracts from interview with Vaibhav Arekar: How did Debotar Grash take root? There has been, for long, a deep desire to explore the mother-child relationship through my medium of art, namely, classical dance, yet something much deeper in its emotional content than the common songs used in dance. Only, incidentally, this festival theme provoked me to search for the same in the literature of Rabindranath Tagore. Thus was born Debotar Grash, my solo dance-drama on the saga of a mother and her child. How did you structure it? Debotar Grash became my frame within which is painted the emotional landscape of a child's innocence and mother's love. The original poem is translated into visual poetry of movements. The idiom, of course, is that of Bharatanatyam. But the free spirit of Rabindranath Tagore, an artiste whose expressions - though articulated in the Bengali language - has the unique energy to touch the innermost chords of universal human emotions, has influenced me and affected the design of my endeavour. What was the outcome? As you would have noticed, Bengali spoken words were interspersed within the narrative texture of Bharatanatyam. The flavour of English poems was juxta-positoned against the original Bengali. Finally, Hindustani music and Carnatic percussion ensemble were woven to create an audio-visual texture of Debotar Grash!  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |