|   |

|   |

e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com The Courtesan Extraordinaire Photos: Neelanjan Basu March 26, 2017 The early Buddhist literature, beginning with the ancient Jatakas, is replete with a surprising number of parables and legends. One such treasure trove is Mahavastu Avadhan which, among others, narrates the didactic tale of the court dancer Shyama and her sudden passion for the handsome stranger Vajrasen - caught on a false charge of theft - for whom she does not hesitate to sacrifice her young lover Uttiyo at the gallows. On the felony being revealed, she is summarily discarded by her 'new' lover Vajrasen. The two main protagonists, Shyama and Vajrasen, are surrounded by the king's minions - headed by a crafty Kotwal - entirely prompted by the power of lucre and the royal dancer's companions acting as a 'voice of conscience,' a well-known ploy inherited by the Bengali folk theatre Jatra essayed by Vivek, literally meaning 'conscience'. Shyama, Rabindranath Tagore's delectable dance drama - presented recently in Kolkata by Jahnavi and Sutradhar - was based on the above story line. The 1938 play (preceded by an 1899 long poem by Tagore on the same theme) was set first in a public avenue, moving to Shyama's private chambers, to the solitary prison cell, to the luxury yacht carrying the lover duo, to the forests on the river bank, and finally to the point of no return. The plot had amour propre played out between the lovers: now infatuated, now querulous and then desperately estranged. The point of view was entirely Shyama's: besotted with passion and eager to elope, the admission of her felony, and her eventual desertion. The mood was of the urgency of the lovers' union, only to fall apart. The tone was, for both lovers, psychologically resonated. The primary beauty of Shyama was the heaving rise and fall of its conflicts and their Spencerian tempo, almost like Western music's overture, leading to the waxing and waning of the passage of ardour between the two principal contenders. As depicted in the performance, the import of Shyama was the overwhelming guilt she bore that made her unacceptable to Vajrasen. The heinous depth of Shyama's sin for making the innocent Uttiyo victim of her 'lust' for Vajrasen - all the more galling because Uttiyo was far too young and yet entirely willing to offer his life - made it seemingly comparable to the Christian guilt, with Shyama as the sinning femme fatale and Vajrasen as the condemning lord, with the same overtones of temptation and manipulation. Vajrasen seemed to be both cursed and be cursed: first at his outburst of love and then at the wretchedness of his situation, of having been saved at such an enormous cost. Not to be overlooked were the other material messages, such as, a foreigner being duped; the rapacity to keep the administration well-oiled at any cost; the money power exhorted by the minions of the establishment; the outreach of wealth ('royal ring') even into the dungeons; and the fatal attraction of sexual favors apparent everywhere. These messages are valid till date! Incidentally, one does recall Rukmini Devi Arundale's showcasing Shyama to celebrate Tagore's birth centenary in 1961, with her choreography using songs daringly rendered in Bengali even for a southern audience. For this, she commissioned Mani Krishnaswamy, the famous vocalist, to learn the original Bengali lyrics. Her dance drama did exceedingly well and Kalakshetra toured Australia with Shyama in 1966. She used Kathakali and Bharatanatyam for her male and female dancers respectively, and improvised with sit down postures, including the honeymoon scene. There was no special stage set. (Pushpa Shankar of Kalakshetra, who played the lead role, could fondly recite the Bengali ditties in 2011, nearly half a century after the original performance!)

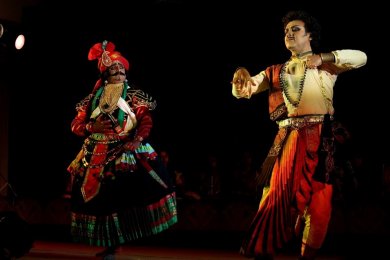

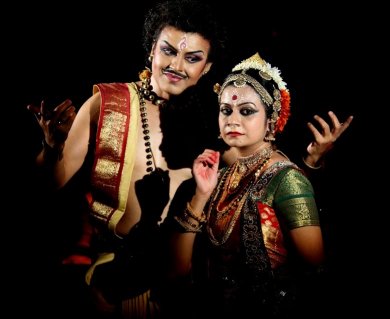

Shyama was directed and choreographed in Kolkata by Madhubani Chattopadhyay (a disciple of Alarmel Valli) who donned the eponymous role - with a blend of Bharatanatyam and Rabindra Nritya - depicting very well the interplay of emotions. But the plum goes to Kaushik Chakrabarty who danced in the role of Vajrasen with a rare sang froid - for both angika and sattvika abhinaya in Kathakali style. Kalamandalam Venkit was equally competent as Kotal using Kathakali, complete with the customary 'horse-ride', which is such a favourite at Santiniketan. Uttiyo was essayed by Devangan, a 19-year-old from Rabindra Bharati University, with great enthusiasm. As is wont with Shyama, there was no set. Excerpts from an interview with Madhubani Chattopadhyay:  What made you go for Shyama? I had never produced Shyama before and was planning for six years. I am a Bharatanatyam dancer and doing Shyama in the orthodox Santiniketan style was a huge challenge. You must also realise that Shyama's is one of the most complex characters created by Tagore to which I needed to do full justice. How did you work out the choreography? Most of it was done spontaneously and mine was more a coordinating job. Kaushik has been a senior dancer performing the role of Vajrasen for many years. Shyama's companions as well as the village girls were from Barrackpore Nrityangan, groomed by Gautam Mukherjee. The dance drama thrives on play of emotions... Absolutely, here the passions and emotions are to be explored layer by layer. There is lust, there is a great betrayal and finally the male angst devastates the female protagonist. There is such a multiplicity of points and counterpoints among the characters. In between, Uttiyo's innocent amour shines like a beacon light. How do you read Shyama's character? At the end of the day, Shyama appears to be a villainous woman. But you cannot help feel for her to have been grievously wronged, since whatever she has done is for the sake of her burning love. Hers is, on the whole, a very complex character and it was a daunting task for me to capture her changing nuances as well as her cataclysmic end. Do you accept that the dance drama reflects, in a way, the 'Original Sin'? Yes, the narrative mirrors substantially the Biblical myth. The narrative does say that Shyama has 'lusted' and must pay for her enormously wrong deed. Vajrasen does take a very judgemental stance over her 'vile' act. To me, these two characters are two opposite poles. The male group dancing didn't seem to be much up to the mark... These dancers were basically singers and very dedicated. They were so keen on dancing that I decided to let them have a go and asked the trained girls to provide them support. Finally, how was the music orchestrated? This was entirely the brainchild of Pandit Biplab Mandal who was leading the percussion. Pandit-ji has been in the field for very long, ever since Manjushri Chaki-Sircar's time. Manoj Murali, with his extraordinarily rich Santiniketan background, was a great help. He also handled Vajrasen's songs while the very promising and very young Priyanka lent voice for Shyama's songs.  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |