|   |

|   |

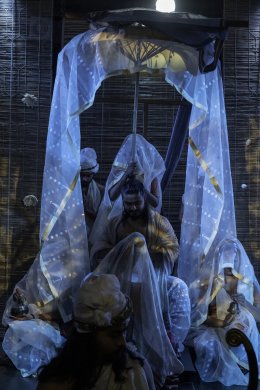

e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com Cloud messenger from beyond borders March 15, 2021 Kalidasa's most famous poem Meghadootam set in motion the genre of Sandesa Kavya (messenger poems) in Sanskrit, most of which were even written in the same lilting Mandākrāntā metre used by the great poet. Meghadootam has around 120 exquisitely evocative stanzas - divided neatly between Purva Megha and Uttara Megha - in which Kalidasa conveys the despondent mood of the Yaksha who was exiled by his employer for a year due to a minor folly, from his home in the Himalayas to the distant Ramagiri hills of Central India. He catches the first monsoon cloud and urges him to take his message to his wife at Alaka on the majestic mountains, by describing many beautiful sights that the cloud shall see on its northward passage until it locates his mon amour awaiting his return in their Himalayan abode. The poem operates at several critical levels. At a sheer poetic level, it is a Khanda Kavya (segment of a poetic work) that meanders in its poetic flow to create rasa (perceptive flavour), dhwani (sonar resonance} and alankara (ornamentation in poetic similes). At an allegorical level, it is the banished Yaksha's flight of imagination where he lets his mind, as his counter-ego, traverse freely across vast distances, creating often real or just imaginary scenarios. At yet another psychic level, it is the parable of detachment where the Yaksha recounts all his attachments to the object of his detachment, creating - particularly in Utara Megha -- almost ethereal images of his object of adoration with an all-seeing eye. The poem's visualisation as a dance-drama in the present situation of our land adds yet another poignant dimension. It is like an anguished cry of an artistic soul, held long in confinement of an incomprehensible pandemic raging around. In many ways, Meghadootam anticipates - across a millennium and a half -- its successor, The Post Office, the lyrical Tagore play, where a terminally ill child is in confinement of his isolated room, creating - through his solitary window - mental images of far-away hills and dales, streams and meadows, cowherds and village belles, curd-sellers and postmen, all from his own vivid imagination!  Meghadootam, christened as Viraha Gatha (Elegy of Separation) and presented on February 17 on proscenium stage by 'Chidakash Kalalay' with munificence from Ministry of Culture, came actually as an overture for a 3-day long Gatha Utsav: Festival of Dance, Music and Theatre: with Padmanka Gatha (play) and Balai (a theatrical monologue on February 18; and a varied fare of Paanch Kaan (another theatre monologue), Dashavidha Rupam (duet-dance) by Akash Mallick and Pinki Mondal, solo music by Debjit Mahalanobis and the final duet music by Debjit and Subhendu Ghosh, all on February 19. But Meghadootam, which only is reviewed here, had its special charm in being primarily an Urdu version (with a smattering of Multani, Sanskrit and Hindi), composed in 1987 by Raja Pratap Singh Gannari, a poet from West Pakistan, who had migrated to India. [Surprising though it may seem, just as Sanskrit poetry has its superbly nuanced meters, alliterations and other decorative features, Urdu sher-shairi (poetic recitations) - especially across the frontiers, as was this critic's experience once in the early 1990s -- has its highly developed Nafasat and Nazakat (beauty and delicacy), guttural utterance of nukhtas (accents), prolonged pronunciation of compound words, and nasalisation of n-sounds at the word's end (like gulistan, Guldastan, et al.) that make its poetry utterly bewitching!]  The performance primarily focussed on Purva Megha where the Yaksha (superbly played by Sayak Mitra) allows his mind (played by Raman Natta on the obverse side of a screen) wander away with the cloud journeying northwards. The transparent screen separates the man from his alter-ego, yet maintaining a harmonious relationship. Shimmering light provides the right ambience to the floating clouds enacted through sculpturesque Marga Nritya by the bevy of swaying torsos of male and female dancers that create light-and-shadow ephemera in a mystical ambience. The cloud's sojourn follows the path of the monsoon that, emanating from the Arabian Sea, floats through Central India and comes to Ramtek where the Yaksha resides, before proceeding towards Upper Tibet, incidentally, reveals another facet of a monsoon savvy poet! Following Purva Megha, the cloud travels to the paddy fields where all the farmers are waiting eagerly for the rains. Then it makes a detour towards the capital Ujjain and comes up on the market place first, with its own hustle and bustle; vendors crying their heart out on the super quality of their wares for sale; an old man weaving his yarn to whoever cares to listen; and a transgender person coursing through the crowds and providing merriments. The cloud then comes to Mahakal temple, where the Aghori priest dances with abandon (beautifully executed by Rudra Prasad Roy). It now reaches the dark lanes and alleys where the maids are stealthily going around to meet their loved ones on Abhisara (love-tryst). Uttara Megha comprising largely allegories imagined by the Yaksha, forms only a brief part of the total narrative, with no attempt made to re-create Alakapuri, the Yakshini's home. The scenario changes to the maidens plucking Brahma Kamal flowers, a rare species that blossom only once in several years. There are also two supra-physical characters, appearing as Vajra Yogi and Vajra Yogini and dancing their Vajra Yoga rituals. When the show ended with stringed harp, bas gongs and Buddhist bells and cymbals playing along, the spectators were left sitting entranced, nearly forgetting to clap!   Excerpts from interview with the director (Kalamandalam Piyal Bhattacharya) and Asst. Director (Sayak Mitra): How did you come across the poem's Urdu translator from Pakistan? The octogenarian Raja Pratap Singh Gannari is actually a Hindi poet who migrated from Pakistan and lives now in Delhi. We were searching the Net at the "rekhta.org" portal for an appropriate Hindi / Urdu translation and reviewed quite a few that we did not like. We came across there, Gannari-ji's translation in a metrical symmetry with the original, which we hugely liked and got into correspondence with him. It transpired that Gannari-ji had adored the poem right since his college days and even had translated the stanza, Dhumrajyoti salila marutham... from Purva Megha right then labouring over a long period! He readily gave us his consent for the dance-drama project and permission under the copyright act. But how did you pick up the Urdu dialogues? Sayak knew some Urdu and Gannari-ji was impressed, over telephone, by his diction. Raman learnt Urdu over several months and both of them got thoroughly groomed under Dr.Azhar Alam, the noted Urdu theatre director in Kolkata. Additionally, Amit Banerjee, ex-NSD, kindly gave us training in the theatre idiom. Purva Megha only mentions the market before reaching Ujjain and an old man spinning yarns. But how did you create the whole market scene? The great thespian Habib Tanvir had, in his essays and in his production of Agra Bazar, described the great bustling Indian Bazar. We followed his ideas and also had a transgender to complete the chaos. The story of the old man was taken from the play Pratigya Yogendharayan by the poet Bhasa and then Sayak composed a Hindi poem based on it, which the old man narrates. You have also used poetic narrative in the Abhisara scene... Yes, this was based on a Brajbuli poem composed by Govinda Dasa. Your aesthetics, both in choreography and narratives, are of a very high order. It is completely stylised, without the least illusion of reality, -- most reminiscent of the Japanese 'Noh' plays... Thank you! In the entire aesthetic process, we used specially crafted bamboo curtains and had commissioned handloom made Jamdani sarees. We attempted to retain an overall transparency in our sets, to mirror Kalidasa's heightened poetic vision in the entire narrative!  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |