|

|

|

|

Seminar on Patrapravesam from Rukmini Devi's dance dramas - Sept 17, 2003 by Prof. A Janardhanan, Chennai November 11, 2003 |

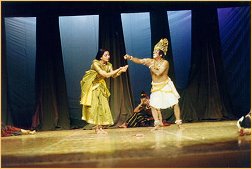

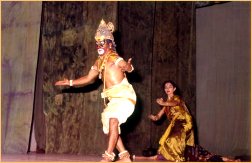

I was brought to Kalakshetra by my father Chandu Panikker in the year 1958, which makes it almost 45 years since I came here. My association with Rukmini Devi spans 3 decades and more. I have literally grown with the institution and she was responsible for having moulded me into an artiste. Not that I have learnt art from her, but I was given the opportunity to talk to her, to go on tours with her, be a part of her activities, be associated with her... I cannot put this profound experience in simple words. It is still so fresh in my mind. I developed into a small artiste, I got the opportunity to teach, I became a performer and finally I was given the opportunity to become the principal of the Rukmini Devi College of Fine Arts. Even though I have retired from this institution as principal a couple of months back, the management wanted me to be here till the Rukmini Devi centenary celebrations are completed. I am trying my level best to make this more colorful, more fruitful and more picturesque from different angles. The whole responsibility of putting up various shows during this centenary year has been thrust on my shoulders because I was closely associated with her during the composition of the dance dramas. So this is a very memorable and vital year in my life. I had conducted a seminar on Patrapravesam on 2nd March and it was suggested to me that I do one on similar lines again. It takes me back in time to Rukmini Devi's period, when I was a very young, timid individual. I have tried to recollect all the information that I learnt from her, through her experience and her choreography, and put all this together into a small seminar. I got these excellent dancers to portray the various Patrapravesams through their group work. The seminar was a grand success since the dancers who attended have requested a repeat performance. I feel I have justified people's faith in me and the task has been very enjoyable and successful. I was happy I could do this in remembrance of Rukmini Devi for all that she has given me. Before moving on to the actual subject, I must emphasise the relation between dance and expression. There is a divide now between pure dance - only dancing - and dance which incorporates mime or verbal syllables. Traditional dance grew in the context of stage acting consisting of speech, physical actions, costumes and make-up. It was enactment of a dramatic work through movement. Can dance then, as Angavikshepam-tala-layasrayam (rhythmical body movement), be seen as a form of physical enactment - Angikaabhinayam - of the play? Bharata asks: "Considering that interpretation through gestures (abhinaya) is devised to communicate the meanings of the drama, and considering that dance movement is neither related to the verbal meanings of the song (which it accompanies) nor directly denotative / expressive of them; why has it been introduced in drama at all?" He answers his own question thus: "Dance does not depend on any meaning to be conveyed and is occasioned by no specific, expressive need, except that it enhances the stage spectacle." Bharata's view could be summed up to mean that dramatic action (natya abhinaya) including gestures and non-rhythmical motions of the body essentially facilitates the rendering of verbal meanings and that dance, even as part of a musical or drama, is something that flows out of the rhythms of the song or percussion instruments. Many have challenged this view of dance as a non-expressive form of action arguing that all physical action (in the context of the theatre) is essentially dramatic and expressive. While hand and facial gestures interpret the textual meanings directly, dance movements bring out meanings not touched upon in the text, like the emotions attached to the meanings...this could be likened to the presence of music in drama that helps brings out meanings not expressed by the words in the text. The argument that there is no direct reflection of content through dance weakens as even pure dance does give the viewer some notion of what is transpiring on stage. Therefore, Nritta is also a form of Angikaabhinayam (dramatic action). But how can the rhythmic movements of the body express emotive meanings, when in actual life people do not show emotion through moving to beat or tempo? This could perhaps be explained in terms of the distinction between Lokadharmi (natural representation) and Natyadharmi (stage convention). Stage presentation is not simply mirroring real-life actions or copying natural movements; it involves the enhancement of these emotive motions by stylisation and choreography. This adds structure to natural movements, extending and intensifying their emotional expressiveness and meaning. An expression enters a dance performance when: a) A pure dance sequence is introduced into an Abhinaya portion. b) Abhinaya is rendered rhythmically in dance steps (Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi, Kathakali). c) The Bhava (emotive import) of a text or action or situation is reinforced or prolonged through rhythmic movement, lending it dramatic significance - as a gestural enactment of that import. For example: the Kalasams in Kathakali. This may be called 'association through structural integration.' Selecting Plays Plays should be chosen with the audience in mind and should not be chosen to showcase the talents of the director or the actors. The standard of the performance should not be cheap and unbecoming nor should it be highbrow. The theme is the main philosophical idea of a play and should be chosen with a view to bring out its values. The selection of these values for the purpose of expressing them optimally is termed 'treatment'. This is the most important element of a production. Interpretation of Characters All characters, even leading ones, should be integrated into the play as a whole. An understanding of the functions of a character is important in interpreting that character. Functions of Characters In a well-constructed play each character serves several functions, and one character dominates. Called the 'protagonist', this character is usually one around whom the plot revolves and is often the key to the interpretation. Most plays also include a character doing trivial errands. Having little value in the context of the plot, their technical importance is considerable. Important characters should be interpreted in a way that makes them dynamic. Movements of Characters Every situation contains motivation for some movement that must correspond exactly to the motive that causes it. For example, when we are repelled, we step back. These movements should also convey the strength of the motive and the character. Every gesture should involve the whole body as much as possible. Timing Timing a movement or gesture perfectly has a great effect on audiences. This skill can be mastered only by experience before audiences. Creating the Character After interpretation, a character must be assigned a characteristic set of movements that best reveal its nature and psychological reactions to the various situations of the play. An actor's approach to characterisation is the key to giving life to the character he plays. He must empathise completely with the character's psyche. Acting Technique The term acting technique applies specifically to movement technique. This is a 3-point technique: a) To help the actor look his best. b) To make the mechanics of movement fluid and efficient. C To choreograph a scene so as not to hide an actor holding centerstage. Stage Design The stage should be designed keeping in mind its importance to the plot as well as different purposes (if any). The overall design should not be overdone. Background The background scenery should conform to the style of the play and contribute as a prop to the plot. Most often, the scenery reveals to the audience the place, time etc. as soon as the curtain opens. The setting therefore must be correct as it helps the audience understand the play. Costumes Costumes must be true to characterisation and also the style of the play. More on Athai... Rukmini Devi struck a precise balance between movement and emotion in all her productions. She approached dance in a spirit of reverence and complete dedication. She insisted that her students respect the sanctity of this art. She detested commercialisation of art, and wanted her stage shows to be well within the reach of the common man. She wanted to reach the general public, not only the 'rasika'. Kalakshetra under Rukmini Devi's direction has produced 26 major dance dramas - 6 of them based on the Ramayana. The Ramayana was her dearest creation and, without a doubt, her greatest. She used the Kathakali technique in all her major productions like Kumara Sambhavam, Sita Swayamvaram, Paduka Pattabhishekam, Sabhari Moksham, Choodamani Pradhanam, Maha Pattabhishekam, Shyama Kurma Avataram and Meenakshi Vijayam. This technique was used for example when vigorous action (Sethubandhanam, Lankadahanam, churning of the ocean), characterisation of non-humans (Hanuman, Vaali, Jatayu) or elaborate miming (asuras, monkeys, Ravana) was required. Her introduction of Kathakali in a largely Bharatanatyam style shows her artistic ability. She did this with skill and without sacrificing the purity of each style. Bringing these two styles together enhanced the dramatic expression of her productions. Patrapravesam The entry of the character in dance and theatre is known as Patrapravesam. For Rukmini Devi, all characters were important. I have selected a few that clearly illustrate Athai's genius of dramatic imagination in her characterization of human and non-human beings. In the dance drama Kurma Avataram, choreographed in 1974, four apsaras appear one after another as devas and asuras churn the ocean. The postures and picturesque scene give the impression of the dancers floating over the surface of the water, clear evidence of Rukmini Devi's choreographic genius and innovation. The verses are from Srimad Bhagavatham. Papanasam Sivan composed the music with the assistance of Thuraiyur Rajagopala Sarma and Bhagavatula Sitarama Sarma, who has composed music for several songs in the dance drama and made necessary modifications under Athai's direction. Demo of apsaras in Kurma Avataram. With the passing away of Mysore Vasudevachari, there was a break in the production of the Ramayana series. Athai felt that his grandson S Rajaram, the present director of Kalakshetra, had fully imbibed his grandfather's sampradaya and urged him to compose music for the rest of the Ramayana series, starting with Sabari Moksham. In the captivating group dance from Choodamani Pradhanam of Ramayana, composed by Athai in 1968, 6 colorfully costumed dancers describe the 'Pampasaras'. To a ragamalika with beautiful tala patterns, sollukattus and swaras, they depict lotus, water birds, bees and creepers. Demo of Pampasaras. The dance drama Sabari Moksham was composed in 1965. Enroute to Panchavati, Rama, Sita and Lakshmana encounter the mighty eagle Jatayu. The eagle's simple and suggestive costume and his realistic movements as envisioned by Athai illustrate her powers of observation. Demo of Jatayu Patrapravesam. To demonstrate a demonic character like Surpanaka in dance, some Kathakali elements have been introduced. Generally in a dance drama, the emotions to be expressed in the lyrics and the abhinaya to follow are hinted at in masruni nritta. It may not necessarily come before the abhinaya part, but may be inserted between passages of sahitya linking them and still conveying the bhava and rasa contained. This colorful Patrapravesam of the ugly rakshasi Surpanaka is from Sabari Moksham. I remember that Athai herself danced to demonstrate the bold movements, the fierceness of the character further accentuated by the movements covering the whole stage space. The dancer who was to portray Surpanaka could clearly comprehend her role on seeing Athai's picturisation. The costume and makeup are appropriate for this demonic character. Demo of Surpanaka Patrapravesam. Ravana's Patrapravesam dance to a song in Nattai, befits his power and strength. While the maids in his court extol his greatness in a thillana, his deformed sister Surpanaka enters in great pain. She tells Ravana how Lakshmana disfigured her when she tried to fetch Sita for him. Ravana consoles her. Demo of Ravana's Patrapravesam. The Patrapravesam of Rukmini is a unique creation of Rukmini Devi. The Patrapravesam song in atana and adi tala is used for Rukmini's nritta as she is seen swaying in an imaginary swing with her sakhis. The dance and abhinaya of the two sakhis describing Rukmini's beauty is a novel way of presenting the heroine. Kalyaniamma presented the Bhagavatamela nataka script of Rukmini Kalyanam to Athai, who composed, choreographed and transformed it into a highly acclaimed temple dance drama. Demo of Rukmini's Patrapravesam.  Rukmini Devi gave Hanuman innovative facial makeup, a suggestive tail, and dance steps most suited to indicate his monkey character, valour and power of flight. Hanuman's Patrapravesam is to a song in Hamsadwani with appropriate sollukattuswaras from the 1968 dance drama Choodamani Pradhanam. Demo of Hanuman's Patrapravesam.  As kavi vakya, the orchestra recites how Sugreeva challenges Vali for a fight. Signifying his coming out of the cave in Kishkinta mountain, Vali emerges on the stage on his knees, moving with ferociously suggestive monkey movements, sounds and jumps as he challenges Sugreeva to a battle. Vali's Patrapravesam to a song in mohanam begins with arohana swaras, with brigas and sollukattuswaras in different gatis. Demo of Vali's Patrapravesam. In Choodamani Pradhanam, Vali's wife Tara demonstrates another example of masruni nritta, meticulously composed by Athai. Having premonition of her husband's death, a troubled Tara enters and tries to persuade Vali to abandon thoughts of a fight with Sugreeva, as it will definitely be fatal. Before interpreting the song through gestures, Tara performs nritta in which the adavus are adapted to the mood of the character. An epitome of arrogance and valour, Vali enters with typical animal characteristics. Tara cautions Vali that Sugreeva has befriended Rama. Vali chooses to ignore the fact, confident of his victory since he had not offended the Lord. Tara's dance brings out her anguish and sorrow for Vali's arrogance and impending doom. Demo of Tara. "Kodai nayaki vandaal, kola nayaki vandaal, Naada nayaki vandaal, gnana nayaki vandal." Andal's Patrapravesam depicts her childlike innocence, playfulness and joy of living. Born to be the consort of Sri Ranganatha, Andal was the daughter of Periyaazhwar who lovingly called her Kodai. The tantalizing tirasheela first reveals only the feet and hands, then the face and when the tirasheela is dropped, the dancer is transformed into the character. Kodai is a mugdha nayika. Having heard stories of Sri Krishna, she innocently falls in love with the paramapurusha. The verses have been taken from the Divya Prabhandam, the music scored by Papanasam Sivan. The group choreography of Kodai and her sakhis to 'namam aayiram' is testimony to Athai's excellence. Though the dance drama was choreographed as far back as 1961, people never fail to be astounded by its brilliance to this present day. Another exemplary group choreography where Kodai and her friends are in conversation is to 'apttimeindador kaareru'. They ask each other if anyone has seen Sri Krishna. Others reply that they have seen him in Brindavan caring for the cows while Garuda's wings formed a canopy over him to protect him from the sun. They describe Krishna as the sun rising from behind Udaya Giri. The dance of Andal and her sakhis portray picturesque dance movements, positions, varieties of grouping and also miming in dance form. Demo of Andal and her sakhis. A Janardhanan is a Kathakali and Bharatanatyam exponent. He has served as a faculty of Kalakshetra for 46 years. He was the principal of Kalakshetra from June 2001 - May 2003 before retiring. |