|

|

|

|

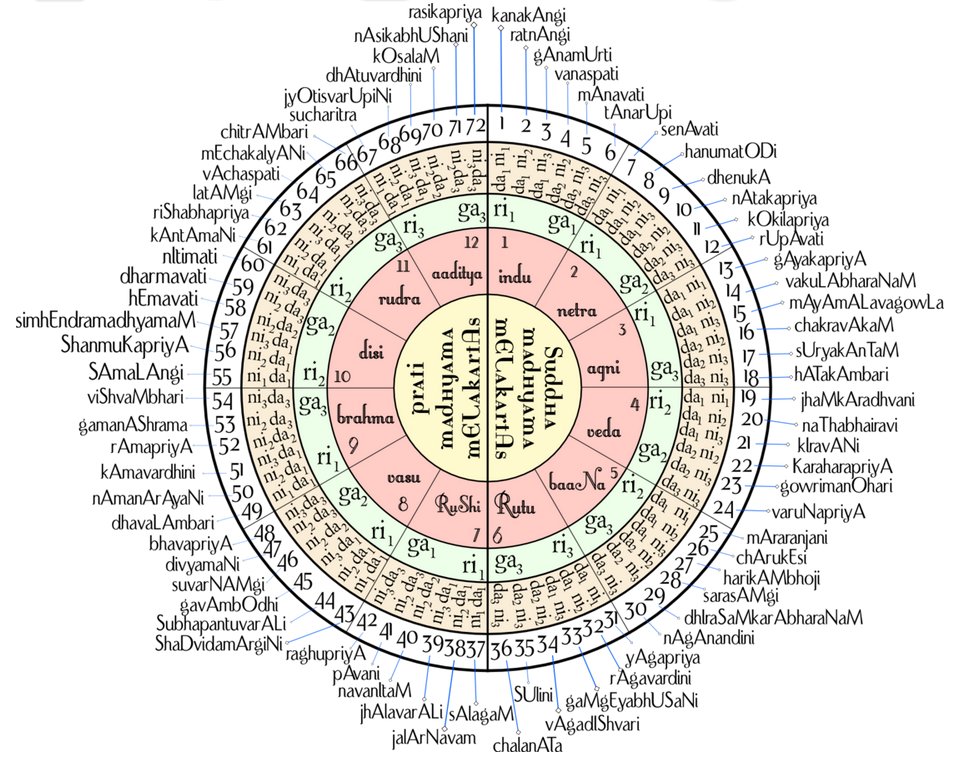

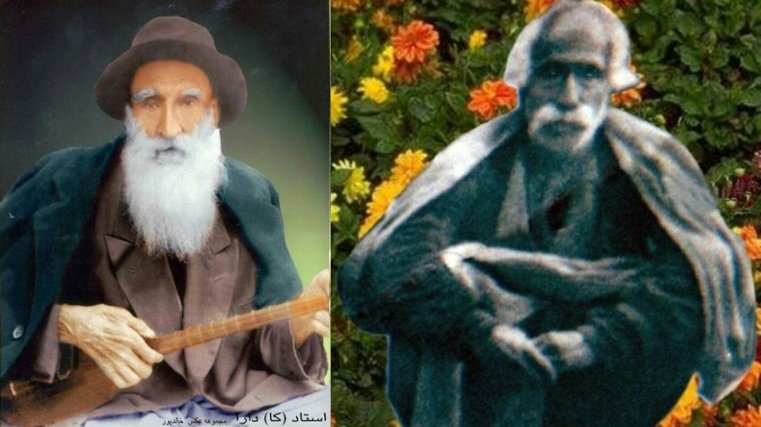

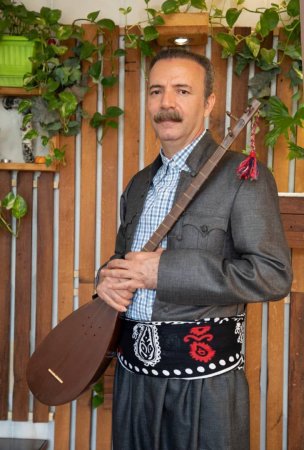

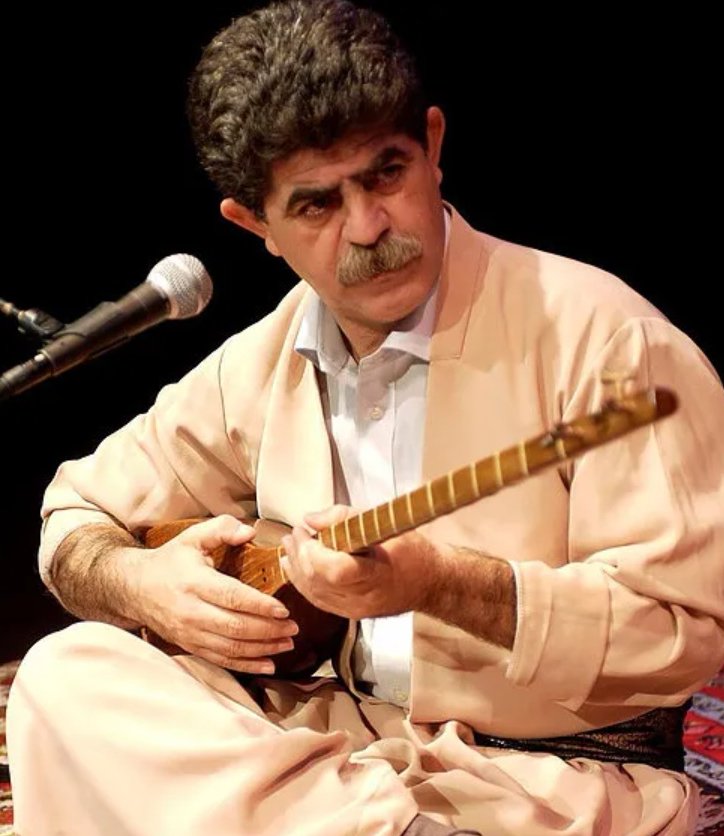

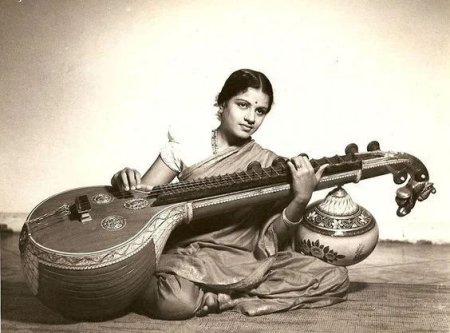

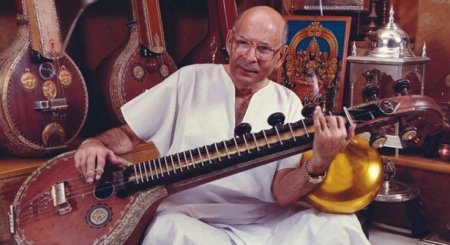

Bonds beyond boundaries- Ranee Kumare-mail: Ranee@journalist.com June 15, 2025 Encased in our cocooned existence, conditioned by misled fervour about the singular spirituality of our music and allied arts, we turn a blind eye to the rest of the world. Our myopic memory makes us oblivious to the fact that there existed ancient civilizations on the globe along with ours. Surprisingly antiquity surpasses time, survives onslaughts of new aggressions on its land and yet, presents the future generations with its treasured art forms that emerge with stamp of eternity. It's astounding that the number 72 in terms of music, has a magical significance across world cultures which we were not even aware of. A brief look into the ancient music systems of Middle East and south of India for instance, will throw up the core similarities of classical music. Just as our south Indian music is based on 72 Melakarta (Janaka) ragas (melodic modes), so too there are 72 maqams (raga/melodic modes) in ancient music of Persia, exclusive domain of Kurdish artistes of Yarsan descent. It's a different matter that now in both systems, the music is being learnt, practiced and presented by many with deep interest and talent in music. The basis and genesis of both music systems is no doubt spiritual. While the Persian maqam follows a totally spiritual division, our music which is nothing but Naada Brahma (melody of creation), is now going by the name of Carnatic music to distinguish it from the later developed Hindustani music and has been fixed into a template which of course, again, has its origin in cosmic sound and letters (dhawni-akshara) that was at the essence of Vedic rituals.  Katapayadi Sutra of Carnatic Melakarta Ragas Let's first decipher why it had to be 72 and not a more rounded off number like for instance 70? Well, going by ancient myth and history this number, though rare, has been in vogue "in almost all linguistic mythologies from Brahmin wisdom to Celtic and north African lore. The original speech had severed into 72 shards." (George Steiner: 'After Babel'.) According to Jean Cooper (An illustrated encyclopedia of traditional symbols), "It is a fundamental principle from which the whole objective world proceeds; it is the origin of all things and the harmony of the universe. In kabbalistic practices the relationship of number, letter and word have deepest mystical significance while also being treated with systematic rigour..." Sounds close to our own 72 Melakarta ragas being systemized through the Ka-Ta-Pa-Ya-di principle. Genesis 10 which is often put forth as a starting point for the tradition in Judaism, Christian and to some degree Islam, lists the names of 72 descendants of Noah, 72 names of gods, 72 old men of Synagogue, 72 disciples of Confucius. 72 is the number of languages that emerged from the Tower of Babel and 72 is the number of hours before Jesus was resurrected from crucifixion. It is also mentioned elsewhere that Pythagoras, inspired by the blacksmith's hammer, fashioned an instrument and arranged musical notes according to the number of celestial spheres. Musical inspiration to human mind was the beating of its own pulse. Now coming to our own tradition, the Akhsara Samkhya (Ka-Ta-Pa-Ya-di) system is believed to have come to limelight from Vararuchi, a Sanskrit grammarian (4th C). There is evidence of its use in astronomical texts though its exact origin remains unknown. The Melakarta system per se doesn't carry direct spiritual or religious significance. Yet, it emanated from the universe of sound and aligns with the cosmic order, much like other order of Hindu thought. The 72 parent (Janaka) ragas are grouped into 12 chakras (wheels) with each chakra comprising 6 raga, thereby making it 12 x 6 =72. These chakras have esoteric / cosmic names like Indu (moon), Netra (eye), Agni (fire), Veda, Baana (arrow), Rrtu (season), Rushi (sage), Vasu (celestial being), Brahma (creator/cosmos), Dishi (direction), Rudra (Vedic god) and Aaditya (Sun) in chronological order. Nos. 1-6 are Shuddha Madhyama raga while 7-12 are Prati Madhyama raga. The Ka-Ta-Pa-Ya-di calculation is a bit mind boggling like any other ancient Vedic formulae. The 7 basic notes (swara) of our music are said to be derived from Nature, from the sound of birds. It goes without saying that whatever be the present form of music with all its technicalities, it is essentially derived from harmonious heavens - be it Nature or universe. Hence it has an innate quality to lift us to a state of sheer bliss.  Old photos of Tanboor artistes  Shekar Khanum Darawi However, the number 72 in this music theory is not an exact mathematical framework (like division of the octave into 72 parts). It carries deep spiritual and symbolic meaning: each maqam is not just a musical mode, but a step on the path to spiritual awakening and unity with the divine. The combination of music and spiritual practice here is what makes it unique and meaningful. The 72 maqams are not an academic or theoretical structure; in the context of Tanboor, the number 72 is often symbolic of 72 distinct vibrational frequencies that guide the musician towards different spiritual stations- each offering a special gateway to the divine or a deeper connection with the Self. It embarks on an emotional/spiritual journey wherein each maqam in the system is like a step on that journey leading the musician through different aspects of consciousness. It is said among the spiritual heads that the full experience of the 72 maqams leads to enlightenment or divine union (Sufi thought). For the Kurdish Yarsan community, one of the original and oldest living ethnic groups of Iran (then Persia), the number 72 represents a perfect circle or what is called, cosmic unity. The music of the Tanboor with its 72 maqams is interpreted as an effort to connect the microcosm of human experience with the macrocosm of the universe; in the process aiding the practitioners align themselves with the cosmos. The frequencies and vibrations of these 72 maqams are said to resonate with various chakra points (energy centres) in the human body, making for a balance and healing imbalances. They can be seen as variations of specific tonal patterns that evoke emotional response. While south Indian music was developed in both instrumental and vocal forms simultaneously, the ancient Kurdish music was developed on a beautiful yet simple lute called Tanboor (plucked string instrument), a far cry from the Tanboor used in our music. Based on archaeological excavations where reliefs of Tanboor players dated 300 years and the existing ancient documents like Grove's dictionary of musical instruments, for instance, the Tanboor is 5000-6000 years old, though its current structure dates back to the 4th-5th century. However, it was the 13th century saint and founder of present day Yarsan faith, Sultan Sahak who endowed the Tanboor with spiritual propensity and it acquired a sacred, ritualistic characteristic and identity as an instrument of his Ahl-e Haqq (seekers of truth) faith. The maqams were codified with specific, mystical and divine themes/content. In the face of historical aggressions and Arabization, this system of music which originated in provinces of Western Iran where most Kurdish Yarsans live presently, would have in normal course been wiped out or annihilated but for their Phoenix-like rise with every onslaught, to hold on and preserve their unique culture, their arts, their language through centuries despite the odds. Periods of low-lying and periods of revival are common to any ancient culture. So too were revivals and regenerations through the darkest of years. The Tanboor instrument almost falling into disuse was revived by Lorestan explorer Shah Khushin (born 406).  Heydar Kaki  Veena and Tanboor A word about the term maqam: it came into vogue in 14th C as a part of Islamic music culture. Earlier, ancient musicians like Farabi and Avicenna referred to different combinations of sound groups as 'Ajnas' (singular) and their formative into octave sequences as 'Jama'ah'. There are three groups of maqams prevalent: Broadly, the maqams got classified as per their mystical character into Haqiqi (original/true) and Majazi (adapted). A distant but nevertheless similarity to South Indian ragas that are profound and others simply devotional or adapted. Ancient maqams like Jelowshahi, Savar Savar and Baya Baya. Another category comprises maqams composed by Dervishes (benevolent individuals) within last 100 years. These are played and sung at holy gatherings (Jamkhana) and Sufi lodges (Khanqahs); hence they go by the name of Khanqahi melodies, according to musicologist Heydar Kaki. Just as the ragas have significant characteristics like for instance Shankarabharanam (jewel adorning Shankara: serpent), the raga movement is suited to certain content and composition, so too the maqams were named to suit specific content for which they were composed. For instance, the lyrical content of Haqqani kalam (mantra) is a tool for purifying the consciousness (atman).  Ali Akbar Moradi Later years saw emergence of gifted and scholarly Tanboor musicians of whom Ramtin Kakavandi is a name to reckon with. A fourth-generation maqam player as he calls himself, Kakavandi tutored under Ustad Sayyed Khalil Alinejad (1375-79) and later under Abdulhamid Sharbatchi and became an adept with maqams. Kakavandi's contribution lies in transcribing the maqams and collecting recorded works of prominent masters and compiling the history of the maqams of Tanboor. As on today, Kurdish musician- Ali Akbar Moradi is a stupendous musician who renders all the 72 maqams on his Tanboor. So much to the preservation of this ancient musical instrument, the Kerend district of Dallahoo (Western Iran) is the seat of Tanboor and was declared in 2021 (Jan 11) by the Iran government as national city of Tanboor.  Lady with veena  MS Subbulakshmi  Veena vidwan S Balachander Another common feature of the Tanboor maqams and south Indian music is the rendition where prominence is given to oscillation (gamaka) of the notes (swara). The practice of both the divine Tanboor and the divine Veena often involves deep meditation. The Tanboor goes a step further in making it a ritualised music where intonation and feeling are vital than strict adherence to the scale of music. To date, a large number of Tanboor players and singers reign over their region with the pride of their legacy that is a prominent part of their identity.  Ranee Kumar is a journalist who brings in three decades of hard core journalistic experience with mainstream papers like the Indian Express and The Hindu to arts reporting. Her novel 'Song of Silence' and guest editing of attenDance widen her horizon. Response * Greetings Congratulations, I read the article, it was excellent. I hope I can invite you to hold a workshop in my country. - Kaki.music@gmail.com (June 17, 2025) Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |