|

|

|

|

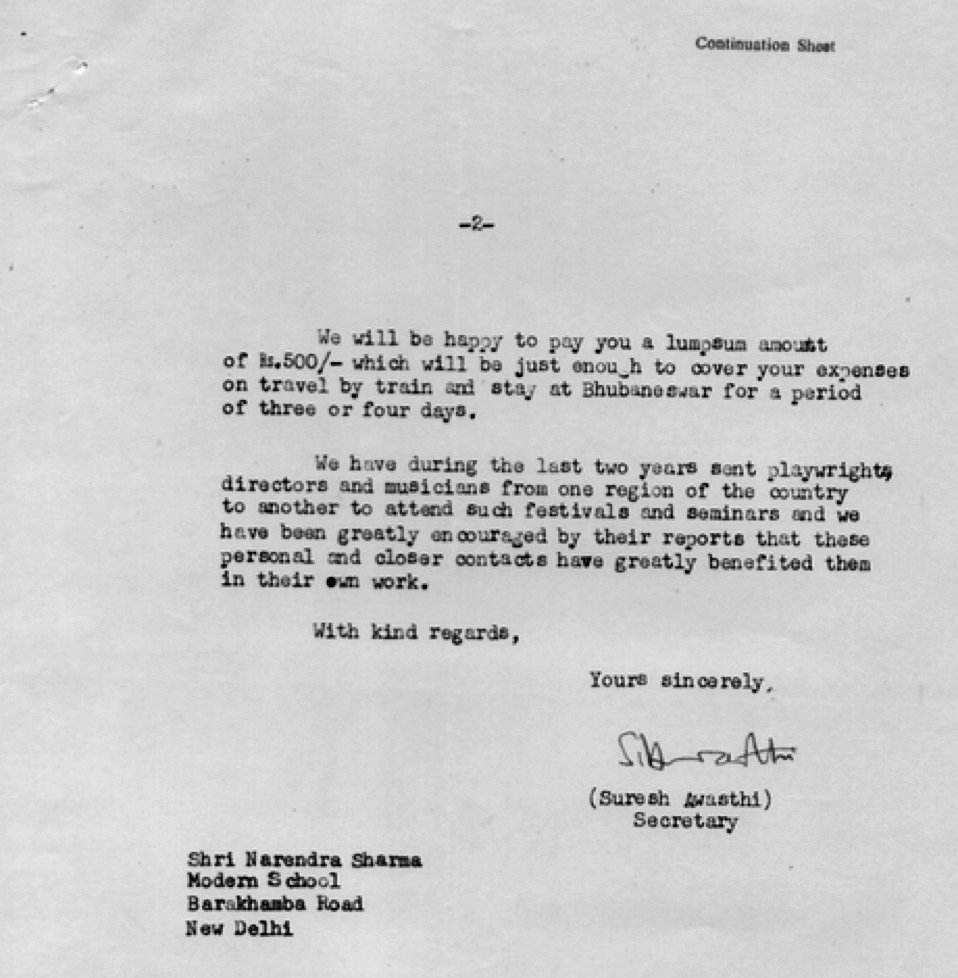

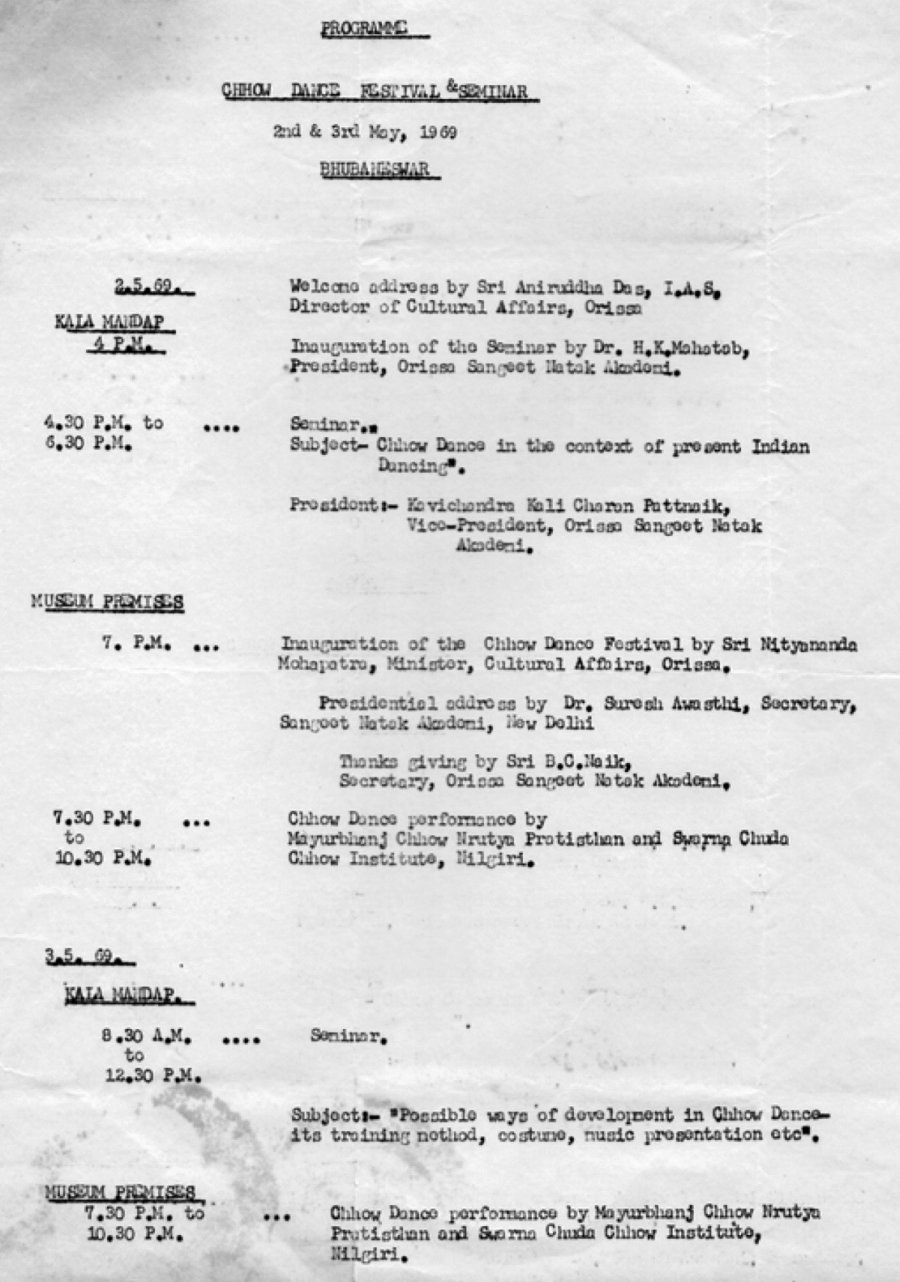

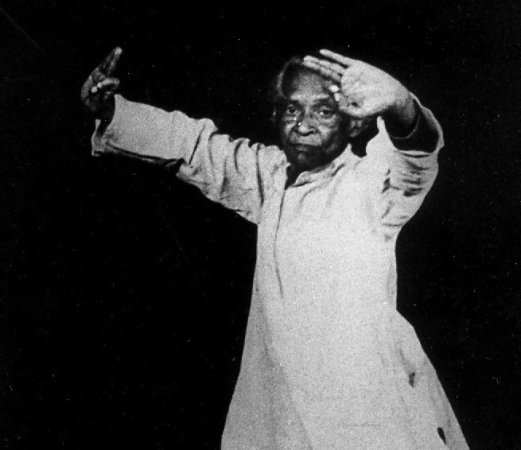

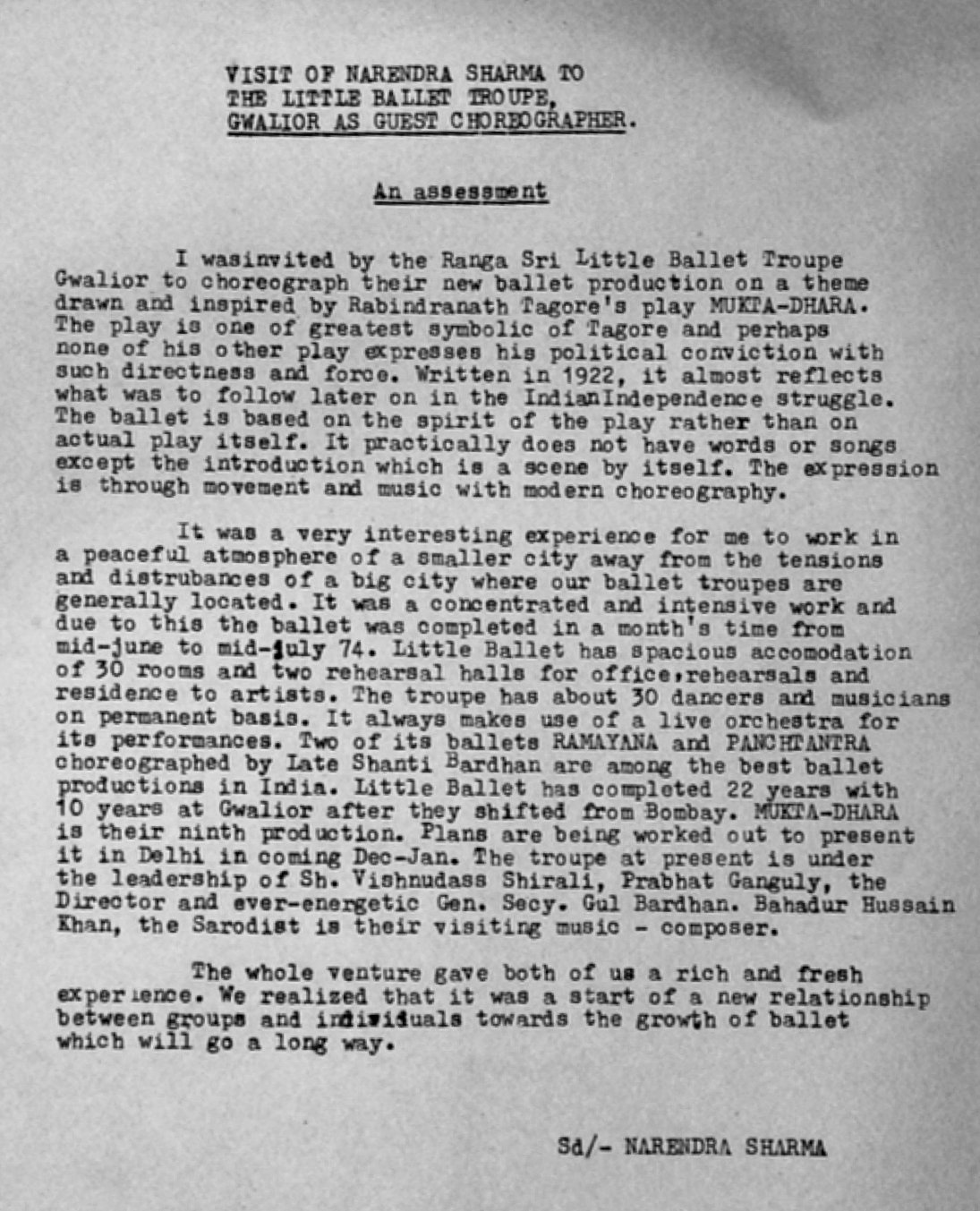

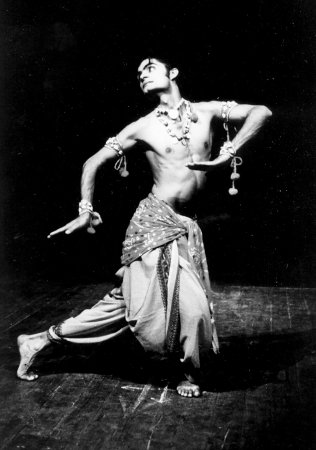

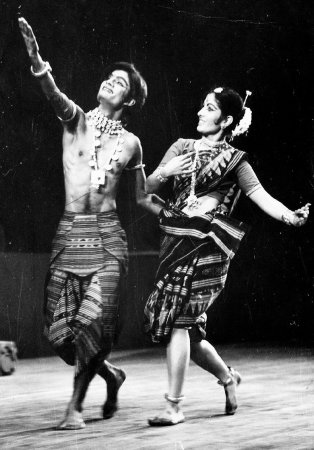

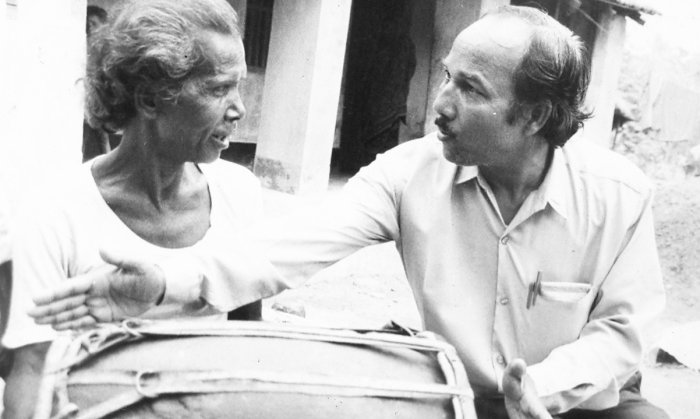

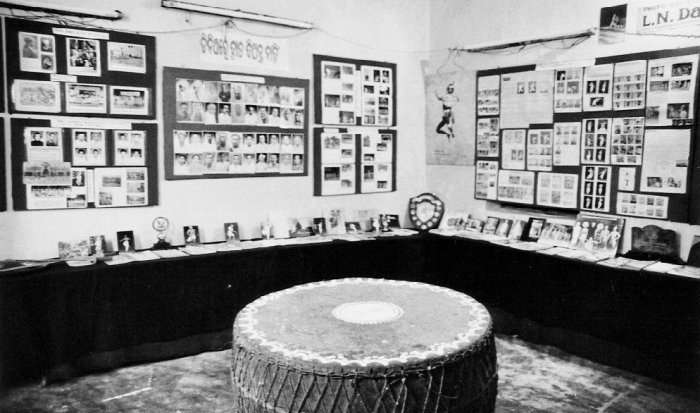

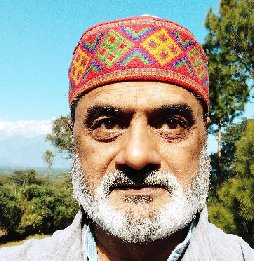

Mayurbhanj Chhau - Bharat Sharma e-mail: bhasha.dance @gmail.com Photos: Narendra Sharma Archives September 27, 2023 (A post from Narendra Sharma Archive, on the 99th Birth Anniversary of Narendra Sharma. Reproduced here with permission) Within the battle-lines drawn around the geographical contours and 'ancientness' of dance 'styles' animating the performing arts scenario in last several decades in India, one 'style' that has been on the margins is Mayurbhanj Chhau. My love for this art form grew from the fascination my father inculcated in me from the beginning of my career.  Marg volume 22 (1968) Amongst the memorabilia Baba left behind for me to dwell upon is the key Marg issue (volume 22, number 1) of 1968 printed from Mumbai that was gifted to me once I started learning Mayurbhanj Chhau seriously in 1976 in Delhi. This volume, which has not got critical attention yet, was obviously a milestone of its time, and remained a benchmark for scholars and students of Chhau style for long. The cover page, with a picture of two dancers from Seraikella Chhau, begins with an emotive editorial by progressive writer Mulk Raj Anand (founder-editor) by placing Chhau as a 'subaltern' amongst dance styles. Thereupon, there are articles by Sunil Kothari on Seraikella Chhau, and by Jiwan Pani on Mayurbhanj Chhau. In each case, there are photographs of two sleek male bodies demonstrating respective techniques - Kedar Nath Sahu for Seraikella and Krishna Chandra Naik for Mayurbhanj. These were perhaps the earliest writings on Chhau in a recognized 'national' art magazine.   Letter by Suresh Awasthi (1969)  Performance Note, Bhubaneshwar (1969) But what was happening in Delhi was far more interesting. Credit goes to Suresh Awasthi, then Secretary of Sangeet Natak Akademi (SNA), to bring a group of Mayurbhanj Chhau dancers and present them in Delhi in September 1967 (see pic of letter). In May 1969, SNA sent a delegation of choreographers to Bhubaneswar to attend a two-day seminar on the style. This delegation included Mohan Khokar, Uma Sharma and Baba from Delhi, and Parvati Kumar from Mumbai, who witnessed performances and lecture-demonstrations (see pic of programme note). These choreographers were requested to give a report for rejuvenation of Chhau. Baba's diary mentions two impressive groups he witnessed - Mayurbhanj Chhau Nrutya Pratishthan and Swarna Chuda Chhow Institute. He also notes the brilliant exposition of dance scholar Jiwan Pani on Mayurbhanj Chhau, and exceptional presentations of 'Shikari' (solo) and 'Kirat Arjunia' (group). The last day of seminar was cancelled due to sudden demise of India's President Zakir Hussein. But Baba's Rs.500 grant for the seminar from SNA allowed him to return via trips to Puri and Kolkata. In Kolkata, he met his teacher Uday Shankar for the last time. This meeting was a poignant one, with his notes revealing a troubled state of mind of his mentor, lamenting and sitting on a 'charpai' inside a mosquito net. However, upon reaching Delhi, Baba described to me at length about his visit, and mentioned about an exceptional dancer he saw in the seminar who could spiral down and reverse it while standing up on one leg - all in slow motion. Later, I came to know this dancer he saw was none other than Krishna Chandra Naik dancing his famous 'Dandi'.  (Bharat Sharma) Performing at Kolkata Seminar (1987)  Guru Krishna Chandra Naik (1978) There was a buzz in Delhi on the 'discovery' of this new 'style' from the East of India. Soon Ashutosh Bhattacharya, folklorist and writer from Kolkata, arrived with a group of rustic dancers of Purulia Chhau, and presented a mind-blowing performance of 'Kirat Arjunia' in the open lawns of Rabindra Bhawan, SNA with a full orchestra - Dhumsas, Dhols and Mahuris. I had never seen a performance of such power, and the spectacular entry of Five Pandavas - their circular jumps and landing on knees on grass - is still etched in my mind. The Purulia group soon departed for their maiden tour of Central Europe where a new approach to study Asian Theatre was formulated. Events that followed were equally dramatic. In late 60s, a Department of Culture was set up within Ministry of Education with dancer scholar Kapila Vatsyayan at helm. Her tenure coincided with one of the most contentious political enigma of free India - of managing the tense relationship of Princely States within the constitutional framework of India, and the question of privileges promised under Privy Purses at the dawn of Independence. Within that delicate framework was also the aspect of arts patronage, as several art forms were patronized by Princely states, like the musicians at Rampur and Maihar state. A long battle in the courts ended with the abolition of Privy Purses in 1971 through 26th Amendment, setting off a frenzy in political circles with international ramifications. This was a blow to Seraikella and Mayurbhanj Chhau, as both were patronized by Princely states. In particular, the Maharaja of Mayurbhanj was hurt on the broken promises by the national leadership. His ancestors had nurtured the dance style with care for more than a century in their court, in their kingdom's capital Baripada, with an elaborate system of patronage with an infrastructure. He had declared that he would nurture the form to perfection before showcasing his accomplishments to the world. With the Privy Purses gone, the last Maharaja, Pratap Chandra Bhanj Deo, decided to abandon the royalty's involvement with the dance form, and even ordered his subjects and artistes to forget their courtly heritage. This also led to a social and political chaos in the lands under his control. There were rumblings in Delhi's art circles too. The first move by Kapila Vatsyayan in her stint at the ministry was a crucial one. She chose Gwalior as a focal city with its rich mosaic of cultural symbolism. With the royal house of Scindias (with their Maratha roots) having lasting influence in the region, the city also had strong roots in Hindustani music. Trained by Swami Haridas, Tansen's 'maqbara' (15th century) was resting next to his other teacher Muhammed Ghaus, reflecting upon the confluences of 'sufi' culture. Tansen was one of the 'Navratna' in Akbar's court during Mughal rule. Soon a festival of classical music was initiated in memory of Tansen which even today is visited annually by eminent musicians and connoisseurs. And then there was the magnificent Gwalior Fort, one of the oldest, evolving into a tourist attraction. In retrospect, this was a well-crafted move by Kapila ji. Gwalior was situated in a corner of northern Madhya Pradesh, a state carved out from several central provinces of British India. Largest in landmass before breakup of the state (Jharkhand and Chattisgarh), Madhya Pradesh - with sparse population - had an exceptionally rich and fascinating cultural landscape. Ujjain was famous for 'Mahakaal Mandir' (with perceived central meridian mentioned in Sanskrit literature passing through), and home to Kalidas's genius and his plays. Dotted with innumerable ancient forts, there were the fabulous Orchha palaces nearby as well as temples of Khajuraho. With Tapti and Narmada, two rain-fed rivers flowing across the Deccan Plateau to Gulf of Khambat into the Arabian Sea in west coast, the state was in the midst of one of the thickest and continuous forest belts stretching through Central India, from Orissa all the way down to Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and even Karnataka. These forests gave home to innumerable folk and tribal communities of India with their exquisite lifestyles and unique cultural manifestations. Perhaps, Gwalior was envisioned as a cultural hub. Soon Little Ballet Troupe (LBT), of late Shanti Bardhan, set up in Mumbai in 1952, shifted to Gwalior in 1964, at the initiative of Rajmata Vijay Raje Scindia. Patel Chatraniwas, with almost 30 rooms, was given to LBT as campus. Gul Bardhan, the fierce Leftist-organizer and Secretary of LBT, was joined by Prabhat Ganguli, a former dancer in Uday Shankar's dance company to become the Resident Choreographer. To top it all, Vishnudass Shirali, the brilliant music composer of Uday Shankar's last trailblazing tours in the US, became the Manager of LBT. Soon sarod player Bahadur Khan, a relative and student of renowned Ustad Allauddin Khan, joined as music composer. This was a heady mix, par excellence! Soon Shanti Bardhan's masterpieces 'Ramayana' and 'Panchtantra' for LBT were to travel to China and erstwhile USSR for months. Dancers and musicians from all walks of life - Manipur, Kerala, Gujarat, Bengal, Maharashtra and more - trained in different styles as well as novices, converged at LBT to participate in their training programme and repertory work in Gwalior. In July-August 1974, Baba was invited by Prabhat Ganguli to choreograph a dance-theatre production on Rabindranath Tagore's seminal play 'Muktadhara' on LBT's group of 30 artists. I remember going to railway station to see him off to Gwalior - he was visibly excited. After almost six weeks he came back, again talking at length at home on this experience - of what he taught and the movements he invented to depict several aspects of Tagore's narrative on conflict between Man and Machines, Purush and Prakriti (see pic of report).  Narendra Sharma's report on choreographing 'Muktadhara' for LBT (1974) Baba's jottings in dairy of his stay at Patel Chatraniwas are fascinating, including a lengthy conversation with Vishnudass Shirali on possible reasons of closure of Uday Shankar's seminal Almora School. But what was even more revealing was the lifestyle at Chatraniwas - there was a 'commune' like atmosphere within the campus. Entire artist community lived together - cooking, eating, working and creating. Perhaps, the spirit of Almora was being re-invented, away from a large metropolis. Gwalior itself was becoming an active cultural center - residential schools, theatre groups, musicians, dancers from all walks of life were settling there. By the 80s, through a series of mishaps, LBT was to shift base to Bhopal which began to witness fresh cultural interventions, in the lake city of erstwhile Begums of Bhopal. Within this excitement in Gwalior, Baba talked about the presence of Krishna Chandra Naik who had already arrived before him to teach, and described his exceptional classes at LBT. In retrospect, Krishna Chandra Naik's arrival in Gwalior changed the 'new directions' of Indian Ballet. In the very first grant-scheme that Department of Culture introduced was the 'salary-support grant scheme', and LBT became the first recipient. This scheme was to facilitate Indian Ballet groups to retain dancers on a 'professional' basis on an annual contractual basis, and to be able to work whole time as a repertory. The grant was meagre, but gave dancers 'jobs'! This time with state funding. This marriage of Mayurbhanj Chhau and Indian Ballet had many sub-texts, which I was able to understand only later. In a brief discussion after a LBT performance in Delhi in late 70s, Kapila ji explained to me this experiment as an exploration of 'space' in technique - in context of collaboration between two groups, two 'collectives' - with contrasting expressive dance vocabularies. LBT was a vibrant group at its peak then, and Mayurbhanj Chhau gave another dimension to their praxis. Kapila ji pointed that given the changing contours of performance spaces in India in 60s, Indian Ballet should open up to find new ways to 'move' in expansive performance arenas. The technique of Mayurbhanj Chhau did provide a unique language of leg gestures for narration in an 'Indian way', as against Modern Dance and Classical Ballet in the West. Only in later years I was able to fully grasp this theoretical formulation, by analyzing the Indian Ballet movement from 40s and a series of events that took place in 70s. Without going into extensive details on this praxis at this juncture, I would like to point to the dance-theatre production 'Bhairavi' that emerged from this dramatic marriage of Mayurbhanj Chhau and Indian Ballet at LBT. This was choreographed just around the time Baba was choreographing Tagore's 'Muktadhara' in Gwalior. I saw this production during first contemporary dance festival that SNA organized in 1976 in Kamani Auditorium, Delhi. This was a mind-blowing production, one of the finest I have seen in my life. I was barely 20! In 1972-73, Krishna Chandra Naik had trained a remarkable group of male and female dancers at LBT at Patel Chatraniwas. The chronology of events thereof was equally dramatic. After the abolition of Privy Purses, the Maharaja of Mayurbhanj put a moratorium on artists practicing the art form in Baripada. Somehow, Krishna Chandra Naik, with a set of drummers were extracted from the region, and sent to Gwalior to train dancers at LBT to much consternation of local populace in Orissa for this flight of artists 'outside' the region. The Maharaja himself was deeply saddened as Krishna Chandra Naik was his favorite dancer, especially for his rendition of solo 'Dandi'.  Royal Palace, Baripada (1995)  Performance in Baripada (1995) In the first contemporary dance festival in 1976 organized by SNA by Mohan Khokhar, Baba choreographed my solo 'Man and the Masks' along with the group piece 'Reflections' adapted from Oscar Wilde's short story 'Birthday of Infanta'. But everybody excitedly talked about LBT's 'Bhairavi'. With Gul Bardhan as the central protagonist, freshly trained in Mayurbhanj Chhau by Krishna Chandra Naik, draped in red 'dhoti' and blouse, she stood as the sacrificial female body at the altar of male patriarchy and macabre rituals of orthodoxy. The narrative explored the Shaivite 'Bhairav'/ 'Bhairavi' tradition and inherent conflicts within context of 'Chaitra Parva' festival in Baripada, with drummers as well as music composed by Ranu Bardhan, younger brother of Shanti Bardhan, who had taken up the baton after Bahadur Khan. It was much later one realized that this production was a masterful adaptation of Igor Stravinsky's 'Rite of Spring' with design by Nicholas Roerich for Ballet Russes during Diaghliev Era. Premiered in Paris in 1913 this landmark production set off riots for the sacrilege of Western Classical Music! Later, through a series of artistic accidents in the 20s, Uday Shankar was to get his international recognition in 'inter-war' years within the churnings of Diaghliev Era in Paris. Perhaps, there was an attempt to connect these threads in artistic lineages in Gwalior! This was the genesis of this seminal collaboration - between the art 'collectives' of LBT and Mayurbhanj Chhau - which has continued to remain unnoticed in arts discourse till now. More interestingly this was almost 5 years before Pina Bausch was to premiere her own version of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring in Wuppertal in divided Germany, and travelled to India only in 1979! I have always wondered why 'Bhairavi' has not been revived since then. Partly this happened because of another mishap that occurred in Gwalior, on the issue of copyright. There was a misunderstanding between Prabhat Ganguly and Krishna Chandra Naik, as to who was the real choreographer of this masterpiece. The issue was, Prabhat Ganguli was the dramaturge and choreographer, and Krishna Chandra Naik the trainer and movement advisor. Both saw respective contributions in their own way in this landmark production. This misunderstanding had a major fallout - there was a spilt, and Krishna Chandra Naik left LBT. However, Kapila ji saw to it that his talent was not lost. She got him to Delhi and requested Sumitra Charat Ram to let him start training their Indian Ballet troupe at Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra (SBKK). Gwalior's loss was to become Delhi's gain! Arrival of Krishna Chandra Naik in Delhi was ominous in 1975-76. As soon as Baba heard that he was teaching at SBKK, he held my hand and took me to the hostel room where he was staying, on second floor, and declared, 'My son is yours. Train him the way you want'. Soon formal classes shifted to first floor of SBKK's new building and my next four years (1976-79) were most critical in developing my 'technique'. I was sheer lucky to learn from my Guru at the creative peak of his career. He would spend hours teaching 'chaalis' and 'uflis' in meticulous details, re-codifying and refining the entire technique. He would experiment on my body and see what new moves could be developed. Clearly his stint with LBT had an effect, and he built on that experience methodically. Soon a fresh bunch of dancers joined at SBKK, and we became a small group who would readily accept his teachings in all its grace. Classes started at 3pm and stretched till 6-7pm. Each day we practiced 6 'chaalis' and 36 'uflis' to begin with. Guruji had some diaries that he would refer to once in a while - notes in Odiya and pencil sketches on postures. He systemized a series of 'Bhangis' the third stage of training. These were fascinating range of preparatory exercises to get students to adapt to the 'stylistic' features of Mayurbhanj Chhau before getting into repertory work. By all means this was very different system of moving with commensurate rhythmic structures from what I had understood till then of techniques in other classical forms. Within a year Guruji started teaching me the solo 'Dandi'! I did not know the full meaning of this 'transfer' of 'oral' tradition till late. He was famous for this dance in Baripada, and his body was not entirely agile when he stood up to demonstrate due to his age. But whenever he got up to show a bit, I was reminded of my father's description of him after his visit to Bhubaneshwar in 1969 - when he saw Guruji for the first time. To add to it was the theme of 'Dandi' - of renunciation, of man proceeding to forest to do penance, to practice the third and fourth stage of life as per Hindu 'way of life' - Brahmacharya (student), Gṛhastha (householder), Vanaprastha (forest dweller), and Sanyasa (renunciate). 'Dandi' was taught to me as my first dance. I found it ironical, as I was still a young college going youth, and with 'Dandi' I was being prepared for 'sanyas'!  (Bharat Sharma) in 'Dandi' (1983)  (Bharat Sharma) in SBKK's 'Kalinga Vijaya' (1979) I wound up my formal training in 1979 with substantive achievements including repertory work, notation of rhythmic structures in Bhatkhande method, dancing in his new ballets and developing a course structure for Indira Kala Vidyalaya, Chattisgarh. I danced in Guruji's SBKK's productions 'Kalinga Vijyaya' and 'Khajuraho' upon his request. And thereafter, took up the task of teaching Mayurbhanj Chhau to dancers of Bhoomika in 1979. I promised Guruji that I would continue to teach and spread the word on what he taught me. I have travelled and practiced far and wide, in India and abroad, and I have tried to 'save' this dance 'style' in my own small way - dancing, adapting, teaching, researching, supporting and advocating. This 'parallel' of mine, to being a contemporary dancer and choreographer, has continued to run through my entire career of over 5 decades, and my fascination for Mayurbhanj Chhau has not waned. Later, in my life, with academic tools of cultural history and anthropology, a whole range of issues surfaced for which I was able to see the performing arts itself in 20th century in an entirely different light, through this dance 'style.' Let me now get to those issues... One of the major problems for Chhau to become a 'mainstream' art form has been to categorize the three distinct forms within India's performing art traditions. By 60s the dichotomy of Classical and Folk was fully entrenched in India's state institutions, as well as private support systems. Some saw Chhau as semi-classical, although one doesn't know which one of them, as Purulia, Seraikella and Mayurbhanj are entirely different in terms of structure, style, praxis, social conditioning and geography. Since Seraikella and Mayurbhanj had evolved technique, it was not possible to categorize them under folk either! Then there were problems emerging from international exposure of the three styles, mostly in Central Europe and the US. This arena then got extended to the geography of Asia in the fraught East-West Relations in the 'post-war/Cold War' era. Within the decolonization process in Asia, there was a wide spectrum of perceptions that Asian Arts were 'different', and needed to be studied in contrast to performance practices in the West. First of all, where does the West begin and end in performing arts, one is confused, since most draw upon the Greek Theatre and Classical Ballet as their source. But the contours of Asia were definitely demarcated by Imperial Powers. By 60s, formulation of Asian performing art traditions got clubbed as Asian Theatre. Interestingly, in India, even National School of Drama was conceived initially by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, as Asian Theatre Institute in 50s before the British model at Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA) got ingrained in the teaching process in 60s. In came the 'Theatre of Roots' conceived by Suresh Awasthi during his tenure at SNA, which was extended during his teaching assignment at New York University in East coast (with Richard Schechner at helm) in the US in 70s where Seraikella maestro Kedar Nath Sahu was invited to teach under the rubric of 'performance studies', with academic discipline of anthropology at the core. Since Awasthi ji was one of the prime movers in bringing Chhau to the forefront in late 60s, this tradition also got clubbed under Asian Theatre. But the irony is, in the Marg volume of 1969 mentioned above, scholars like Sunil Kothari, Jiwan Pani and writer Mulk Raj Anand, and later choreographers, saw Chhau as dance. By then, in the US, there were several departments in universities which were set up to study Asian Theatre. Baba went twice to West coast of the US in 1964 and 65, his last visits, to teach at Department of Asian Theatre in Seattle, in a collaboration with playwright and theatre director, Balwant Gargi. In Central Europe there were other key theatre directors and playwrights who began interacting with Asian performance traditions including Jerzy Growtoski, Bertolt Brecht and Eugino Barba. With Purulia Chhau's tour in 70s, the fascination for its visual appeal grew, more as an exotica. Then there was the fight between the 'mainstream' and 'fringe' theatre which culminated in the controversial visit of Peter Brook in mid-80s to observe Purulia Chhau in East India, which got reflected in scenes of his Anglo-French production 'Mahabharat' at Avignon, France - Ganesha wearing a Purulia Chhau mask! There was yet another category that emerged in this tryst with Asian Theatre in the West - that of Martial Arts, especially with regard to Japanese and Chinese traditions. Within the paradigm of Post-War Individualism, which took extreme positions in the performing body, violence had to be internalized. In India too, strangely, scholars started categorizing the Chhau as Martial Art, pointing to the word Chhau itself being derived from Chhauni (army cantonment). This was the time Kalaripayattu came to the fore in South India... During discussions with Guruji in Delhi in mid-70s, I saw his visible dismay at these set of categorizations. His assertion was simple - yes, there were traces of Mayurbhanj Chhau originating in martial practices of the region, such as the offence-defense routines - the 'rook maar nach' - but things evolved in due course to make it a full-fledged dance form with elaborate technique, repertory, theoretical framework and aesthetics. Even in 'chaalis' and 'uflis', although delineated with swords and shields, movement imagery was derived mainly from daily household activity of women, natural phenomena, animal gaits and human behavior. Themes of repertory ranged from tribal stories to Puranas, mythological characters in Ramayana and Mahabharata, as well as philosophical concepts. Later, I did some research and found that Maharajas of Mayurbhanj (kshatriyas) were a shrewd lot. They had armies but they negotiated treaties with dominant rulers over several generations, to keep the identity of their kingdoms secure. Since there was prolonged peace in the region, the 'rook maar nach' was a way to train and keep armies in state of readiness. It was only in 19th century that these offence and defense routines of army were adapted to develop the dance style and technique.  Festival of Chhau, Mokukchun, Nagaland (2020) But most important element was that Mayurbhanj district was situated in thick forest region with several tribal communities (including Gonds, Santhals, Munda, Kol and others). There were other intermediate castes that lived in villages and small towns. As a means for cultural and political integration, the Maharajas encouraged the artistic manifestations of these communities to be imbibed in the dance style they patronized. The masters of music were called the 'ustads' and of dance the 'gurus', and through elaborate patronage system, artists were retained all year round. Actual practice sessions followed the agricultural cycle - starting on 'Dussera' day, and ending in April during Chaitra Parva (mid-April) when the main festival started with elaborate rituals of Bhairava/Bhairavi sacrificial cult, followed by several days of performances by two groups - Uttar Sahi and Dakshin Sahi. In contrast to Seraikella Chhau, the royal household did not dance themselves on stage, but set up two separate groups to compete with each other - one patronized by the Maharaja and the other by Rajmata. Each commissioned new choreography each year. As such, the issue of categorizing such a performing art form was definitely a problem in 60s and 70s, given its social composition, art practices, and royal patronage. It was even difficult to see through theoretical framework of 'Natya Shastra' - primarily being the absence of 'hasta mudras' and 'nava rasas', although one could argue that it was part of 'lok dharmi' with elements of 'natya' in it. The rhythms and melody were a far cry from any classical structure - both Hindustani or Carnatic. Besides, this was an ensemble oriented art form, which the 'Natya Shastra' is totally silent on - it's a 'shastra' of developing the craft of an 'individual' performer. Another critical aspect was that this dance style was populated by 'subaltern' community - castes and tribes - who lacked the power of advocacy within the dominant upper castes. As long as the Maharajas had a hold over their kingdom, there was a system of negotiation between the ruler, the subjects and the outside world. Once the hold of the Maharajas was taken away with the Privy Purses, the entire region's economy and social relations became chaotic. During the British rule, those areas saw substantive growth of extractive industries like mining, which became more intense in post-Independence period. Mayurbhanj district continues to be situated in one of the most poverty stricken regions of the country. As such, even today, most dancers and musicians come from depressed classes. Quite a few are rickshaw pullers, butchers and labourers, who come together to put up a programme whenever opportunity comes their way. Internecine wars between gurus and groups is another problem which discourages potential patrons.  Kashinath Barik with local drummer (1995) For me, another occasion to go deeper into the study of this dance form came during my tenure as Programme Director of India Foundation for the Arts (IFA), Bengaluru in 1995 when I facilitated and monitored a grant to Kashinath Barik in Baripada for conducting research in Mayurbhanj Chhau. I found yet another layer in the 'local' issues of the form. It appears there were several attempts from state and central government to evolve a support system in 70s and 80s, but most of them failed. In one such instance, Kashinath Barik himself was involved when a grant was given to train a talented bunch of young dancers at Mayurbhanj Chhau Nrutya Pratishthan in Baripada. In the midst of the programme itself, one 'impresario' appeared from Bhubaneshwar who whisked away the entire lot of dancers for some obscure 'foreign' tour to Europe. The entire effort came to a standstill! Kashinath Barik introduced to me some other aspects that were more fascinating. During my first visit he took me to an impromptu exhibition of rare photographs at the premise of Nruthya Pratishthan. These were eye-openers. One was with the Maharaja and British Governor General from Kolkata in 1903-4 who had come to do a recce for a presentation of dances to newly appointed King Edward VII to British throne during his planned state visit to the Delhi Durbar. There was one more interesting photograph - an attempt of 'ustads' to write Chhau music in Staff Notation of Western classical music system. Luckily, this set of critical photographs is now with SNA.  Exhibition on Mayurbhanj Chhau (1995) I pursued these leads thereafter. In 2003, I saw a documentary on Discovery TV Channel, a black and white film on the Delhi Durbar of 1911. A regal and imperial ceremony, available on YouTube, marked the accession of George V to the British crown. It depicts typically the relationship of Princely States with the Crown. Amongst much fanfare and display of march-past by armed constabulary, the Princes turned up to pay their obeisance to the Crown and Queen. Amongst these is a clip of Maharaja of Baroda showing his displeasure, and the presence of Begum of Bhopal. But one short clip, which I saw earlier, has disappeared since then, that of dance of 'Hatyaur Dhaura' danced by 64 male dancers of Mayurbhanj Chhau in front of the dais. 'Hatyaur Dhaura' could be termed as dance with martial antecedents, because the dancers wielded swords and shields. It is clear that the same dance was shown to Governor General in Baripada in 1904. Which means that the technique was already developed and the dance was ready for presentation. Guruji taught me and a group of dancers some excerpts from this dance in Delhi. Since there were no 64 dancers, that too males, only a few sections were taught. But whatever Guruji explained on the scale and intricacy, this dance had exquisite choreography with varied rhythmic structure and complex group patterns. Ironically Guruji's teaching of 'Hatyaur Dhaura' became a strange cyclical occurrence - while the Maharaja presented the dance to King George V at a ceremony just close to Delhi University's north campus at Kingsway Camp in 1911, I had learnt it at SBKK's first floor studio in Lutyen's Delhi in mid-70s. This cyclical movement of the dance choreography, if analysed closely, had several trajectories that reflected upon the evolution of India's dance in 20th century. 1911 was a crucial year both globally as well as for Indian national movement. India's national anthem was composed in 1911 by Rabindranath Tagore. Division of Bengal in 1905 had shaken the British rule in the East, and Great Power rivalry had erupted in Europe leading to tension between British and Russian Empire. Capital was shifted from Kolkata to Delhi in 1911 to checkmate these tensions, with Afghanistan as the buffer state. 1911 was also critical as World War 1 was just 3 years away, and with the collapse of Hapsburg Empire, the foundations of Europe and their colonies was in jeopardy. It was only in 1919 that Paris Peace Conference was held to temper the upheavals in Europe, leading to new cultural interventions in 20s. And it is this timeframe between 1914 (the end of World War 1) and 1939 (the beginning of World War 2) that becomes important to revisit, in terms of dance history, as these are the 'inter-war years' which every dance historian refers to describe the 'revival' of India's dance heritage in Indian sub-continent in 20th century. The performance of Mayurbhanj Chhau at Delhi Durbar poses a very interesting timeframe just before the break of World War 1 (1914) to the printing of Marg's volume (1969) in Mumbai. In such case, we are then talking of a chronology where Tagore was yet to intervene in dance (1920s); Vallathol was yet to set up Kerala Kalamandalam (1930); Bharatanatyam was still to graduate from 'sadir' (1930); Ram Gopal was yet to take India's dance to the West; Rukmini Devi's Kalakshetra and Uday Shankar's Almora Centre were yet to be established in 30s; and Kathak was yet to arrive in Lutyen's Delhi in 50s from Lucknow and Jaipur...We may have to re-think the dance 'revival' in 20th century all over again within the 'nationalist' discourse! At another plane, the support system evolved by the Maharaja for this ensemble oriented dance form gives a totally different perspective as against royal patronage of Hindustani musicians and dancers, or 'devadasis' in terms of inside and outside the temple structures, or for that matter, the way state and private institutions intervened in post-Independence India in supporting dance. Ironically, even SNA began to recognize Chhau in 60s, and UNSECO recognized Chhau as a living 'intangible' heritage in 2010 - the only Indian dance form to be recognized by the international organization, which incidentally was set up only in 1945 after World War II! However, Chhau's arrival in Delhi in 70s did provide an impetus for initiatives to support the art form in Bengal, Orissa and Jharkhand, in the East. While Purulia and Seraikella gained from their exposure in Central Europe and the US, Indian Ballet and contemporary dance groups started making Mayurbhanj Chhau as essential element of training programme for dancers. Many groups adapted the style in Kolkata, Bhopal, Delhi and Bengaluru, while some soloists included Chhau dances in their repertoire, especially Orissi dancers who saw the style as a male counterpart in a gendered perspective. This even had an impact on nomenclatures - Chhau and Contemporary, Chhau and Orissi, Kathak and Chhau, and of course several manifestations in theatre - 'Theatre of Roots' to Folk Theatre! I have also witnessed a school of dance criticism, where any attempt of raising a leg in performance was considered a derivative of Chhau. There were even attempts to interpret 108 Karanas of Natya Shastra sculpted in holy Chidambaram Temple in South India, as 'source' of Chhau! This spread has helped in creating awareness, but still falls short of giving substantive support to this dance style. The worst off has been Mayurbhanj Chhau. This dance form now needs advocacy to be supported in the form of a fully-supported school and professional dance company, pretty much close to the structures of Classical Ballet in the West. One hopes the effort by SNA in 2018, to set up a Chhau Center at Chandankiyari near Ranchi, Jharkhand, with all three forms of Chhau under one roof, bears fruit! To conclude, I am reminded of my childhood when my parents took me to every performance of Chhau in Delhi, and the particular day in my youth when Baba held my hand to take me to learn from Krishna Chandra Naik in 1976. It has been a fascinating journey which I have never regretted. Chhau may be considered a dance style of the 'margins', but can be truly seen as Dance of the Forests!  Bharat Sharma's career in dance spanning over five decades is marked by diversity of experiences as performer, choreographer, teacher, writer, composer, film-maker and arts administrator. He currently leads Bhoomika, New Delhi. Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |