|

|

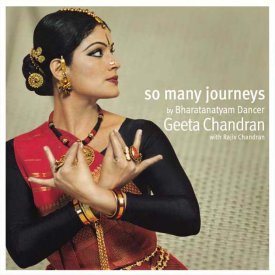

The artist and the artiste

April 5, 2005 Review of ‘So Many Journeys’,

by dancer Geeta Chandran

|

It

is always a pleasure to see a beautiful book that is profusely illustrated

and lavishly produced. But the trouble with a beautiful book is that we

get so engrossed with the pictures that we tend to skip the text - something

like what happens when a man escorts a stunningly good-looking girl. All

eyes are on her; few take notice of him. It

is always a pleasure to see a beautiful book that is profusely illustrated

and lavishly produced. But the trouble with a beautiful book is that we

get so engrossed with the pictures that we tend to skip the text - something

like what happens when a man escorts a stunningly good-looking girl. All

eyes are on her; few take notice of him.

Geeta Chandran’s So Many Journeys is a book both to see and to read. It is a superb celebration in photographs of the art of Bharatanatyam as expounded by a dancer of great talent and dedication, who is currently at the height of her powers. Some of the best-known photographers of the country, among them Avinash Pasricha, Baldev Kapur, and Vandana Kohli, have come together to help Geeta Chandran demonstrate the steps and stances and hand gestures and facial expressions that form the vocabulary of the Bharatanatyam tradition. She is a person with a sense of colour and a striking stage presence. It might be argued that Geeta Chandran is too young to write an autobiography. But the long years spent as probationer, practitioner and interpreter of a specific dance form entitle her to discuss the problems, both organisational and aesthetic, that a career in the classical arts entails. Dancers have to start young. If they wait too long, the body would have lost its suppleness. Geeta was just five when she decided that dance was her life. She had the good fortune to learn the art from leading preceptors like Swarna Saraswati, K N Dakshina Murthi, Jamuna Krishnan, and Kalanidhi Narayanan. Now she runs an institution of her own named Natya Vriksha, which imparts instruction in dance. In chapters entitled "Guru Dakshina," "Navadarshanam," "Rasika," and "Bhakti," Geeta Chandran, besides describing her evolution as a dancer and her experiences in various parts of the country and other lands, discusses the relation between the guru and the disciple, the problems arising out of the conflict between tradition and the new frontiers of the arts, the relationship between the dancer and the audience, and the mythological content of our dance narratives. Then follows a separate chapter, "She Rahasyam" in which she examines the gender dimensions of dance. She concludes with "Samarpan" in which she offers her observations on the art scene.

A little bit of social history would clear up this riddle. Unlike the literary and graphic arts, the performing arts were looked down upon and condemned as corrupting influences by the self-appointed guardians of public morals. Among the performing arts, dance got the worst deal. The dancer was regarded not as the custodian of an ancient cultural heritage, but as a provider of physical gratification. The leaders of our cultural and political renaissance were highly puritanical in their outlook and they were unanimous that social hygiene demanded the banning of the devadasi and nautch professions. Among those who sang and danced in the temples were some artists of rare worth, but our social reformers had no time to consider the need to conserve these treasures. Their attitude is well illuminated by what a leading editor of South India, Khasa Subba Rau, wrote as late as 1946: "Shrimati Rukmini Arundale has rescued the old art of dancing from disrepute and imparted respectability to it. For grace and perfection of performance, Bharatanatyam in our time has scarcely known any to beat that peerless adept, Balasaraswati. But Balasaraswati is just a performer. Rukmini Arundale is a crusader, a crusader bent on winning public appreciation of the place of art in living and Bharatanatyam in art." This astonishing statement from a person held in high regard in intellectual circles in the South India of his day shows that when respectability and not intrinsic authenticity becomes the measure of an art form, its rules, its values and its history itself tend to be rewritten. In order to become acceptable, classical dance thenceforward had to be severely conformist. The Bhakti aspect had to be emphasised and the secular association played down. We find Geeta Chandran writing unselfconsciously about "God and I" and saying, "As a classical dancer I am deeply moved by both the formless Brahman supreme and also by the saguna gods who are replete with form, myths, attributes and values." At the other end are iconoclasts like Chandralekha, already mentioned. There is little doubt that the average contemporary girl would find it a bore to go on playing Yashoda chastising the butter thief or a gopi ready to share the lover boy with 16,000 others. So we find a great deal of experimentation and innovation in all our classical dance centres. Not only Kalakshetra and the Shri Ram Centre, but every dance school and guru with any pretensions are busy producing dance dramas which are suitable for the modern audiences. If there still are those who complain about Bharatanatyam being unfriendly to innovation, the question to ask them is: have you tried? Geeta Chandran

also appears to subscribe to the view that you are an artist only if you

have the freedom to innovate, and a mere craftsman if you are content to

reproduce what someone else has created. If this is the sole test, I should

like to ask: what about the great actors, such as Laurence Olivier and

Sybil Thorndike? Actors do not innovate: they are expected only to interpret,

which they do night after night. Yet could we say they are only "artistes"

and cannot be called "artists"?

H Y Sharada Prasad was adviser to Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. |