|

|

Infusing new energy into ancient traditions by Shanta Serbjeet Singh, New Delhi e-mail: shanta@asia.com April 24, 2003 How do senior Indian dancers who anchor television programs, create websites, travel the global pathways for performances and lec-dems, in short do a million things alongside dance, deal with the material of their dance – its sahitya, its core concerns, its basic leit-motifs, all very orthodox? Do they discard them for newer software or do they recast them in a more modern language? |

|

| The

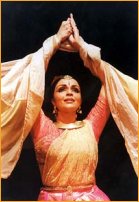

latter, of course. The concerns do not change. Take Anita Ratnam’s dance-theatre

presentation on the 12th century Alwar poet, Andaal, also known as Nachiyar.

It was standard Bhakti Shringara stuff, knitting the poetry that Andaal

addressed to Lord Vishnu with the elements of the story of her life.

But what set it apart, in its unfolding at the Tamil Sangam last week,

where Anita brought it for the Shanmukhananda Sabha, was the entire modernist

approach of stylised choreography; elements from the twilight of dance’s

history. Like Bharata’s over-2000 year old Natya Shastra. Take the opening

Sthapanam scene, where the theatre space is consecrated and the guardian

deities invoked. Four polished female dancers and one very taut male rendered

this long scene with both energy and beauty. Again, when Anita enters

for the first time, it is from behind the transparent, guaze curtain which,

too, is part and parcel of ancient theatre practice. But she doesn’t use

it as just a prop for entry of the main character as one sees it in Kathakali.

She wraps it around her body and the piece of transparent tissue becomes

a host of interesting images, a garland, a mirror, then again a flute and

a little later a stream of running water! Andal Pravesham is now accomplished,

comfortably spanning several millennia.

Anita is by now an established choreographer. The many images that signify Vishnu were conveyed by the dancers standing in a straight line and constantly interchanging with the mudras and the different poses pointing to Garuda, Gurvayoorappan et al. The opening of the evening with the incredible conch playing by Thirukurungudi Kailasa Kambar for full three minutes without drawing a single breath into his frail, one-hand span wide chest, turns out to have a choreographic purpose as well. Andal addresses Vishnu’s conch and through the language of dance we understand why it is called Paancha Janyam. Set by composer and lead singer, the nonpareil O.S. Arun in Kalyani and Vasantha ragas, the sancharis by Anita explain how the conch came to the surface from its bed in the bottom of the ocean. When Vishnu’s other avatar, Lord Krishna, vanquished the demon and ground his bones into smithereens, the particles were shaped into the conch that now adorns his lips. In the very first verse, Karpooram Naarumo, Andaal asks: how do his lips taste? Do they smell of camphor or do they evoke the lotus? Anita’s portrayal stayed on the politically correct line of acceptable shringara but the liberties the poets of yore took with subterranean erotica were quite evident! The procession

of the Utsava Murthi in Thirukurungudi was recreated onstage with the ritual

verses from the Kaisika Natakam. Andaal is now in the throes of viraha.

Revathi Sankaran, the actress who introduced the evening as Anadaal’s mother

comforts her with a moving portrayal. In a dream sequence Andaal

recounts the details of her wedding to Ranganatha. This is set to Hamir

Kalyani and the verse is scored as a tillana, danced by the whole repertory.

Finally Andaal is a bride and on her way to a reunion with her lover. Suddenly,

the religiosity of the lines don’t matter. It is the joy of any woman going

to meet her beloved. Nachiyar becomes an aesthetic jump across time!

|