|   |

|   |

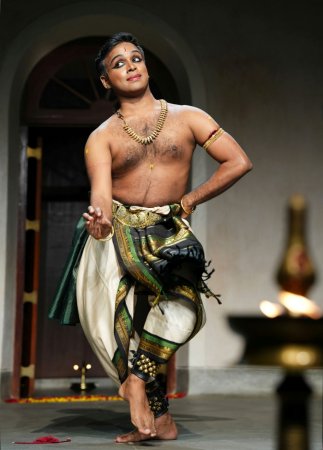

Sparks from Varnamala: Igniting moments in a triptych of Varnams- Satish Surie-mail: satishism@yahoo.co.in Photos: Prof.K.S.Krishnamurthy January 5, 2026 'Varnamala' at Sabha Bengaluru on the 12th of December, was a constellation of sparks, each varnam a flare illuminating Swati Tirunal's timeless genius through the lenses of three masterful artistes. Curated by the visionary Mavin Khoo for its second edition, this intimate gathering in the restored heritage space called Sabha drew a floor-sitting crowd into the raw pulse of nritta and abhinaya. Rooted in the Maharaja's melodic legacy, the triptych - three varnams, three dancers, three journeys - blended tradition with "contemporary sensibilities," evoking devotion's fire in raga Dhanyasi's shadows, Shankarabharanam's radiance, Todi's tenderness and beyond. As the ankle bells faded into echoes, these were the moments that lingered, kindling inspiration long after the lights dimmed. Archana Raja and Dhanyasi flame: Mystery meets acrobatic grace At its heart was Archana Raja's rendition of Swati Tirunal's Dhanyasi Varnam ("Ha hanta vanchitaham"), a piece that pulsed with the raga's enigmatic melancholy, choreographed with exquisite restraint by her guru, Kasi Aysola.  Archana Raja Archana Raja, Artistic Director of Laya Dance Company and a Bay Area based Kuchipudi exponent with roots in Bharatanatyam, entered the stage not as a distant deity but as the nayika herself - deceived, desirous, divine. Clad in a shimmering red saree that caught the low lights like rippling lotus petals, she embodied Pankajanabha (Vishnu) through shringara, her abhinaya weaving Sanskrit sahitya's lament ("Oh, alas, I am deceived") into tangible yearning. The pallavi's opening jatis set a rhythmic hypnosis in Adi tala, Archana Raja's footwork slicing the air with Kuchipudi's trademark precision and playfulness. Yet, it was the nritya sections that elevated this: her eyes, lined in kohl, flickered from coy entreaty to stormy reproach, mirroring Dhanyasi's shadowy gamakas that evoke a heart adrift in mystery. Aysola's choreography infused "beauty and sensitivity" into the form's challenges - first-time immersion for Archana in this varnam, she shared, soaking in the raga's "mysterious" allure. The svara sahityam unfolded like a confession: fluid arudis (ascending phrases) in the anupallavi built to teermanams where Archana's torso arched in supplication, hands forming the katakamukha to grasp at elusive grace. Backed by a stellar ensemble - Chitra Poornima's vocals soaring with raw emotion, Yashwant Hampiholi's mridangam tracing the raga's contemplative bends, and Shashank Chinya's flute whispering secrets - the music never overwhelmed but cradled the dance. A standout moment came in the charanam's etvakaaras (flourishes), where Archana's mandi (squatting) spins dissolved into jaru (slides), her body a canvas for Swati Tirunal's bhakti erotica, blending austerity with abandon. Archana's Kuchipudi lens added acrobatic vitality - leaps that defied gravity, laced with kovvutu (shoulder isolations), honouring the composer's Travancore heritage while nodding to Andhra's earthy vigour. Shankarabharanam - Kavya Ganesh's breathless viraha What distinguished Kavya Ganesh's approach was her sensitive integration of nritta and abhinaya. Rather than employing jathis as formal punctuation, she absorbed rhythmic movement into the emotional continuum. Fluid araimandi extensions, sweeping teermanam inspired pathways, and finely calibrated footwork accents emerged as extensions of the sthayi bhava rather than as self-contained displays. This integration heightened the sense of continuity, allowing geometric precision to coexist with emotional vulnerability. A trembling alapadma suggested the heart's agitation; a sustained katakamukha gaze invoked the beloved's lotus eyes. Physicality thus became the primary vehicle for viraha's immediacy - controlled yet exposed, restrained yet charged.  Kavya Ganesh Kavya's interpretive intelligence lay in her refusal to overstate. The opening passages were restrained, almost conversational, the abhinaya calibrated to the intimate register of a confidante's whisper. As the sahitya invoked bees hovering over flowers and the call of cuckoos - images that traditionally signal renewal - she inverted their promise. A subtle tightening of the jaw, a lingering glance that failed to find rest, transformed seasonal abundance into emotional provocation. Nature, in her reading, became an accomplice to separation. The varnam's poetic similes were rendered with tactile clarity. The comparison to the nipa flower - blossoming only with the arrival of rain - was etched through a trembling stillness: eyes moist yet unblinking, hope suspended between fear and anticipation. This was waiting as lived time, not a decorative metaphor. When the nayika recollected the "most tender lotus feet" of her Lord at night, Kavya softened the torso and slowed the breath, allowing memory to move through the body before resolving into devotion. Rhythmically, the choreography balanced expansiveness with economy. Jatis punctuated the narrative not as interruptions but as emotional commas, marking turns in thought. The dancer's command over line and pause ensured that the varnam's length never sagged; instead, it accrued density. Particularly striking was the transition into the praise of the beloved - his elephantine gait, his regal confidence, his mastery of amorous play - where admiration did not eclipse vulnerability. Kavya held both together, suggesting a dependence born not of weakness but of intimacy. The concluding appeal - I have no other refuge - arrived without melodrama. By then, the audience had been led to understand that refuge here is not rescue but recognition: the beloved's compassion, the friend's remembrance, the promise of return. Kavya closed the arc by returning to the confidante, completing the circle of address with quiet insistence. The musical ensemble played a crucial role in sustaining this delicate balance. Led by Chitra Poornima on vocals, the orchestra navigated extended passages of Ata tala with assurance and adaptability. Poornima's singing was marked by clear diction and expressive warmth, animating the sahitya. Vijay Kumar's nattuvangam formed the rhythmic spine of the presentation; his crisp cymbal articulations and precise teermanams guided the Khanda Jati subdivisions with quiet authority. On the mridangam, Yashwant Hampiholi contributed dynamic vitality, his resonant strokes echoing the geometry of the nritta while cushioning the fragility of abhinaya. Shashank Chinya's flute added an ethereal layer, his fluid phrases evoking Shankarabharanam's sunlit longing. Completing the ensemble, Gopal Venkataramana's veena lent depth and gravitas; its sustained gamakas and subtle plucked resonance grounded the raga's brightness, enriching the performance with a quiet, anchoring warmth. In "Indumukhi Nisamaya", Kavya Ganesh offered a reading of the Padmanabha varnam that privileged psychological truth over spectacle. Her performance affirmed the varnam as a living form - capable of holding layered emotion, seasonal imagery, and devotional surrender - while reminding us that the most compelling longing is often the one articulated with measured breath and luminous restraint. K. Sarveshan: Todi's tender intercession - "Dani Samajendra Gamini" Sarveshan's interpretation of Swati Tirunal's Todi pada varnam "Dani Samajendra Gamini" brought the evening to a contemplative close, foregrounding the sakhi's role as mediator and witness. Approaching the varnam through a male lens, Sarveshan articulated feminine pathos not through overt transformation but through emotional clarity - an approach that curator Mavin Khoo underscored for its authenticity. Set in Adi tala, the varnam unfolded with a measured inwardness that suited Todi's plaintive character. Its lingering nyasas found embodied resonance in Sarveshan's poised restraint. Suchi hastas directed attention toward Padmanabha's indifference, while gentle torso undulations suggested the nayika's gait with quiet empathy rather than imitation. The pallavi line "Tapam iha kamini" was articulated through subtle eye-work that bridged divine apathy and human longing, allowing emotion to surface without overt dramatisation. In the charanam, images of birdsong and humming bees emerged vividly through sahitya-swara alignments, with briefly clenched kapittha hastas conveying the irony of spring's beauty intensifying suffering.  K Sarveshan Sarveshan's multidisciplinary grounding informed his movement vocabulary without overwhelming the varnam's aesthetic core. The angular nritta of the mukthayi swarams was articulated with clarity and control, footwork precise and grounded, suggesting contained energy. His training under the Dhananjayans lent structural discipline, while contemporary sensibilities surfaced in the economy of transitions and sustained stillness. Sarveshan's embodiment of the sakhi marked a significant curatorial statement. His approach eschewed performative gendering in favour of empathetic clarity. The sakhi was neither dramatised nor effaced; instead, she emerged as witness and advocate, her mutedness carrying its own authority. Sarveshan's movement vocabulary balanced angular adavus with fluid jarus, allowing the nayika's tenderness and Padmanabha's indifference to coexist within the same corporeal frame. A standout moment was the inventive visualisation of "pulling a string of bees" to conjure their hum - a creative gesture that heightened the irony of spring's vibrant beauty, amplifying the nayika's torment. Even a momentary repeat of a jathi - to correct a missed beat - felt authentically human, drawing the audience deeper into the shared experience. The understated closing phrase offered a sense of completion that gently unified the triptych, affirming mediation as both theme and method. The accompanying ensemble - Chitra Poornima on vocals, Shashank Chinya on flute, Yashwant Hampiholi on mridangam, Gopal Venkatramana on veena, and Vijay Kumar on nattuvangam - brought depth and cohesion to the presentation. The flute and mridangam, in particular, shaped Todi's inherent pathos with nuanced sensitivity, enabling the varnam to settle into a quiet, introspective resolution. Varnamala succeeded not as a display of disparate items, but as a curated conversation. It argued compellingly that tradition, when engaged with intelligence and courage, offers boundless terrains for discovery. Archana Raja revealed devotion as mysterious and acrobatic; Kavya Ganesh framed it as an insistent, uninterrupted soliloquy; and K. Sarveshan presented it as an act of quiet advocacy. As the final tala faded, what lingered was the powerful resonance of Swati Tirunal's music and the enduring potential of the varnam to kindle inspiration, proving its relevance anew for a contemporary audience.  Bangalore based Satish Suri is an avid dance rasika besides being a life member of the Music and Arts Society. |