|   |

|   |

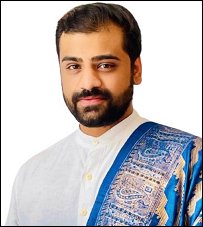

The Sun, the Body, and the discipline of form- Anurag Chauhane-mail: anuragchauhanoffice@gmail.com Photos: Archana December 24, 2025 It is rare for a Bharatanatyam performance to enter a space like the National Gallery of Modern Art (Mumbai) and claim it without explanation. No preface, no didactic framing, no attempt to soften the form for unfamiliar eyes. Yet this is precisely what happened when Ananga Manjari took the stage. Bharatanatyam arrived whole, unhurried, and self possessed, allowing the audience to meet it on its own terms. Bharatanatyam has always carried this quiet authority. Rooted in the Natya Shastra and sustained through the rigor of the guru shishya lineage, it does not seek relevance through adaptation but through depth. In Ananga Manjari's Pushpanjali, this depth revealed itself through proportion, restraint, and a clear understanding of when stillness can speak more powerfully than movement.  Ananga Manjari, a Peruvian Italian dancer trained in ballet, contemporary dance, and Bharatanatyam, has chosen the demanding path of Indian classical dance with uncommon seriousness. A disciple of Guru Dr. Janaki Rangarajan, who has guided her since her early years in Peru and continues to do so in Mumbai, her practice reflects sustained discipline rather than surface engagement. This commitment is evident in the way her body listens before it moves. Her stance is secure, her footwork articulate without insistence, and her transitions marked by patience rather than urgency. The form does not sit on her like an acquired costume. It has been absorbed. Pushpanjali, traditionally an opening salutation offered to the divine, the guru, the musicians, and the audience, unfolded here as a meditation on shared civilisational memory. The work drew from verses of the Aditya Hridayam attributed to Agastya Muni and poetry in Quechua, one of the most ancient languages of South America. The sun emerged as a common point of reverence, Surya and Inti meeting not as symbols to be explained but as presences to be inhabited. The choreography allowed these ideas to surface obliquely through vertical reach, grounded stillness, and moments where the body seemed to pause in contemplation. The image of Pachamama, the Earth Mother, was suggested with equal restraint. Weight settled into the floor, movement slowed, and balance became expressive. Bharatanatyam's ability to convey meaning through stance and alignment came sharply into focus, reminding us that in this form, philosophy often resides in posture as much as in gesture. Choreographed by Dr. Janaki Rangarajan, the work was structured as a Ragamalika anchored in adi tala. The musical architecture was shaped with care by a sensitive and responsive ensemble. On the mridangam, Rakesh Pazhedam provided rhythmic grounding marked by clarity and restraint, while the nattuvangam by Parur MS Ananthashree offered precise articulation that guided the dancer with quiet authority. Vocal support by Preeti Sethuraman carried the melodic line with warmth and control, complemented by the violin accompaniment of Shreelakshmi Bhat, whose phrasing added depth and tonal continuity to the score. Together, the musicians sustained an atmosphere where movement and sound remained in thoughtful dialogue.  Ananga's abhinaya was understated and assured. Expression emerged through gaze, timing, and restraint rather than exaggeration. Her stage presence was calm yet commanding, creating an atmosphere of shared attentiveness within the auditorium. It was evident that the audience, many encountering Bharatanatyam in such a setting for the first time, was drawn into this quiet confidence. Towards the end of the evening, a spontaneous moment shifted the energy of the space. Invited to respond to unfamiliar, non-Indian music, Ananga accepted the challenge without hesitation. Rather than abandoning her classical grounding, she chose to interpret the foreign musical cues through Bharatanatyam. The brief improvisation was neither gimmick nor novelty. It revealed a dancer secure in her training and willing to engage with the unexpected without compromising form. What remained after Pushpanjali was not the impression of cultural fusion or spectacle, but of conviction. Ananga Manjari's performance reaffirmed that Bharatanatyam does not dilute itself as it travels. When approached with seriousness, patience, and respect for lineage, the form carries its cosmology lightly yet firmly within the dancing body, illuminating shared human ideas with grace and quiet authority.  Anurag Chauhan, an award-winning social worker and arts impresario, combines literature and philanthropy to inspire positive change. His impactful storytelling and cultural events enrich lives and communities. |