|   |

|   |

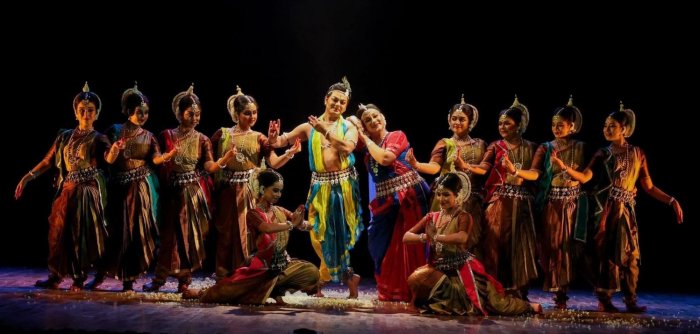

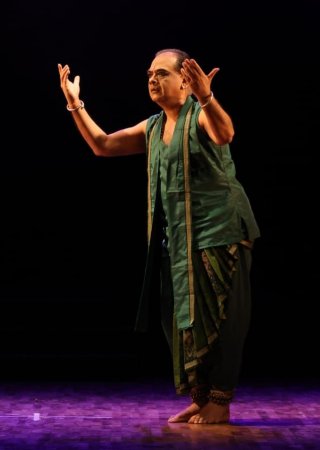

Chitrangada and Ravash- Tapati Chowdhuriee-mail: tapatichow@yahoo.co.in October 8, 2025 CHITRANGADA Photos: Rana Banerjee The first sign of morning is enveloped in the red colour of dawn. Its first influence is felt while still half awake. Finally, the morning emerges in its own flawless brilliance to a world that is fully awake. Similarly love bonds at first sight blinds one with its outward splendid beauty, later to be emancipated from this illusion to the aura of true love which shines magnificently in its own glory. The realization of true love is the core philosophy behind Rabindranath Tagore's dance drama Chitrangada. A lyric of eternal beauty written in his mother tongue Bengali is the prologue to his dance drama. Chitrangada has touched upon the idea that beauty is truth. The prologue says: Illusions of the enchantress, decked in shining golden rays, has come to the garden of youth quietly in nimble steps, to capture hearts in the midst of total darkness. Flute music in the wind and shadow spread a magic spell, testing the vow of sadhana of the Sadhu binding him from all sides to break his meditation. Love is personified and beckoned to come with beauty and truth shorn of all pride; break all illusions; discard pretentions to rescue manhood! The poet has woven a story around the king of Manipur, who according to Shiva's boon would beget male heirs to his throne. Belying it when Princess Chitrangada was born, she was brought up like a male warrior well versed in the art of warfare, acquainted with the nitty-gritty of running her state. Eventually she became the ruler of the kingdom of Manipur. After the completion of 12 years of exile Arjuna, the third of the Pandava brothers, ventured into Manipur to fulfill his life as a Brahmachari. And this is the starting point of the drama.  Madanaa and Chitrangada Chitrangada encounters Arjuna's wrath, when his meditation was disturbed while she was on a hunting spree with her companions. She is overwhelmed. For the first time she recognizes womanhood. She has fallen in love with Arjuna but her love is unrequited. Chitrangada suffers. Filled with love yearnings she is bent upon winning her love. Love God Madana becomes her accomplice. She entreats him to grant her physical beauty to captivate and secure Arjuna's love. She tells Madana that well versed in manly activities, she has never aspired to learn the art of stealing a man's heart. He repudiated her love saying that he was a Brahmachari vowed to his mantra. She asks Madana to transform her with grace and heavenly beauty to captivate the bachelor. Madana's magical spell cast on her captivates him. Chitrangada tries to come to terms with her new-found glory but is remorseful and pensive. She's happy to be with Arjuna, but not so happy for her impersonation leading to delusion. Bewitched by her beauty, he gives up his vows of Brahmacharya and basks in the glory of new-found love, though remorseful Chitrangada warns him that his love is as fleeting as a dew drop.  Arjuna and Chitrangada Arjuna chances upon the fact that the ruler of the country is a brave and able female, and he is eager to know her. Chitrangada tells him that the woman he is so restless to know is ugly and does not have the wiles of capturing a man's heart. In the final scene, Chitrangada asks Madana to take back the beauty he had bestowed on her. Chitrangada shorn of her outward beauty is revealed to Arjuna. In the final scene, Chitrangada tells Arjuna that she is 'Rajendra Nandini' - daughter of the king - who is neither a Devi nor an ordinary woman who can be offered prayers to or not taken into account at all. The beauty of truth is revealed and Arjuna is gratified to recognize Chitrangada's true self who is no less than him. The dance drama Chitrangada was presented as 'Rooper Atit Roop' at Rabindra Sadan, Kolkata, on the 17th of August 2025. The dance style used in its presentation was mainly Manipuri of Guru Bipin Singh style, but other forms like Kathak and Nava Nritya were also used. Dances were composed and choreographed keeping in mind the lyrics of Rabindranath Tagore. For example, in the hunting scene the dance style was modern in the true sense of the word, because no particular genre of dance style was adhered too. Purbita Mukherjee is a graceful dancer and did justice to both the roles - Prothoma and Dwitiya - of the protagonist Chitrangada. Her expertise in abhinaya brought out the essence of Chitrangada's character. Her part as the beautiful Chitrangada portrayed her inner conflict very realistically.  Chitrangada in her Surupa form Her students Shrestha Bandopadhyay, Arundhati Datta, Krittika Roychowdhury and others were incredible. Their performance besides good dancing involved quick dress changes and added the required finesse to the dance drama. Kathak dancer Sourav Roy as Madana with his group of dancers was rather innovative. Dressed in white, the dancers whirled in circles to create the right illusion for the transformation of Kurupa Chitrangada to Surupa. Light designs were excellent. Dim lights used during the transformation of Chitrangada's looks were highly effective. Rintu Das in the role of Arjuna showed his true mettle as a dancer. Priyangee Lahiri, Durba Roychowdhury and Prakriti Mukherjee vocalized the songs of the main character. They sang their way into the hearts of aficionados that evening. Pratyush Mukherjee lent his sonorous voice to the songs of Arjuna, while Arjun Roy vocalized Madana's songs warm heartedly. Direction and script by ace Rabindra Sangeet artist Pramita Mallick of Bhowanipur Baikali Association was commendable. The play starting with Chitrangada opening her heart to Madana about how she was put down by Arjuna and telling the story in flashback was quite creative. The sets used were appropriate as were the sound effects. The forest scene was realistic as were the animal calls. Rabindra Sadan was bursting to the seams that day. SUBIKASH MUKHERJEE'S RAVASH Photos: Arijit Roy Ravash was a flowing landscape of dance conceptualised and presented like a cascading canvas for rasikas at Rabindra Sadan, Kolkata. Sankalpa Nrityayan's artistic director Subikash Mukherjee, impeccably trained in the Odissi dance form at the Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra Odissi Research Centre, flagged off a very beautiful evening of Odissi dance with Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay's Vande Mataram, composed in raag Desh in taal Ektali. The sonorous voice of Trishit Choudhury enhanced the beauty of the dance. Mardala artist Soumya Ranjan Nayak's playing helped make the piece reach its artistic height.  Vande Mataram Selected as the National Song of India on January 24, 1950, Vande Mataram was the mantra of Indian revolutionaries and nationalist leaders during the country's struggle for freedom. The monsoon raag, coupled with the powerful four-beat rhythm cycle, never fails to create magic. As it did that evening with Subikash Mukherjee accompanied by his co-dancers Sreetamaa Gupta, Poulomi Mukherjee, Mrittika Mukherjee, Sreejoni Sen, Madhuma Ganguly, Moumita Sengupta, Anushka Sarkar, and Suparna Dhar. Together they created moments of ecstasy. Each line of the song held surprises at every corner, with quick changing designs of beauty planned meticulously for an enduring audience attention. The choice of the Rabindra Sangeet "Nrityero tale tale" in raag Khambaj, with each stanza of the song tuned to four different taals of Dadra, Sasthi, Kaharwa and Jhaptaal, was a listening pleasure, as was the visual enjoyment of the silent melody of the dance addressed to Nataraja and his cosmic dance in Odissi style. It was a lyrical journey where music, movement, and mood came together in harmony.  Tuhu Mama Madhava "Tuhu Mama Madhava" was the brainchild of Subikash Mukherjee. In his quest to find the best of lyrics throwing light on the many facets of love experienced by Radha, Subikash Mukherjee has used ashtapadis from Jaydeva's Gita Govinda as well as Rabindranath Tagore's Bhanusingher Padavali - heavily influenced by Vidyapati - for their lyrics. In spite of many differences between the two works, both deal with sringara rasa. It is the prerogative of each rasika to draw aesthetic delight from the sahitya of their choice. The Gita Govinda and Bhanusingher Padavali speak of the love between Radha and Krishna. Krishna is physically present in Gita Govinda, whereas in Bhanusingher Padavali, his invisible presence is seen through Radha's yearning - the longing of the individual soul for the supernatural. Krishna frees mortals from the bonds of existence, preserving life in heaven, earth and the underworld. He is the immortal lover. Divine musical notes drifting from the flute of Krishna, the upholder of the Universe, mesmerize and enchant the world. On hearing the strains of the flute, Gopis leave their households for Vrindavana, to the banks of the Yamuna, with their hearts overflowing with love. Inspired by Vidyapati, Radha and not Krishna is the protagonist of Bhanusingher Padavali, the lyrics written from the perspective of Radha. Tagore found that art and aesthetics are intertwined with each other and are mutually dependent. About art, Tagore himself has written, 'Art, like life itself, has grown by its own impulse, and man has taken his pleasure in it without definitely knowing what it is.' Rabindranath Tagore's portrayal of the 'abhisara' of Radha displays Radha's anguish caused by Krishna's subtle way of calling her by playing his flute, summoning her when torrential rain and dark clouds prevent her from listening to his compelling call. The lovelorn damsel is torn apart, but bedecked and bejewelled, she resolves to undertake the arduous journey to meet Krishna, when poet Tagore - in his own inimitable way - pleads with her not to venture out on a night which is beset with danger. The choreographer Subikash found the lyric so beautiful that he could not resist using it in his dance drama, just as he could not ignore the ashtapadi from the Gita Govinda displaying Radha's anguish, who waited the night long, only to be greeted by her remorseful lover at the break of dawn, with telltale signs of having spent an amorous night with another, which also bemoaned separation. Sringara (eroticism) and viraha (separation) are two of the principal emotions of both Gita Govinda and Bhanu Singher Padavali. The theme of love in separation is dominant in the relationship of Radha and Krishna and counterbalances the frenzy and ecstasy of their union. It is precisely this sentiment that is thoroughly used by poets from Jayadeva to Rabindranath Tagore in their songs that delineate their relationship. The participants, besides Subikash Mukherjee himself, along with Reshmee Roy, Sreetamaa Gupta, Sreejoni Sen, Poulomi Mukherjee, Mrittika Mukherjee, Suparna Dhar, Moumita Sen Gupta, Madhuma Ganguly, Anushka Sarkar, Debomitra Halder, Jaysree Dutta, and Debanjana Chatterjee's rendition, helped in bringing out the essence of the piece. Narration was done by Amrita Pandit and Sourav Chakraborty.  Subikash Mukherjee  Ratikant Mohapatra "Dinabandhu ehi ali sri chamure" by Banamali Dasa, was an invocation piece addressed to Lord Jagannath, tenderly addressed as Dinabandhu—the eternal friend of the humble and the downtrodden. The poet desires to dwell at the feet of the Lord for eternity, as expressed in the evocative line, "Sri Ranga charan sebare mo mana." Drawing from the spiritual depth of this sentiment, the choreographer Ratikant Mohapatra has enriched the performance by interweaving timeless stories from the epics. He cited in the Odissi dance language the cases of King Bali - whose pride as a very generous alms giver was humbled by Vishnu in his Vamana rupa - Ahalya, who was restored to life by Lord Rama, the incarnation of Vishnu, and Kewat, the humble boatman who washes Rama's feet and ferries him across the Ganges. The poet Banamali Das quotes an umpteen number of cases showing Vishnu's transformative powers. Further, the poet describes himself as a wandering mendicant in the sacred city of Puri, witnessing the Lord's festivals throughout the year for spiritual nourishment and grace in the company of saints. Instead of worldly comforts, the poet longs for a glimpse of the Nilachakra—the divine blue discus atop the temple, symbolising eternal protection. Chanting "Hare Krishna" becomes his mantra directed towards gaining salvation. The sahitya of the poem in raag Jogia and taal Jati and Ekatali was evocatively performed by Ratikant to the delight of connoisseurs. The piece stamped Ratikant as an excellent male solo dancer, besides being a guru. It was choreographed by Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra to a composition of Ramesh Chandra Das.  Tapati Chowdhurie trained under Guru Gopinath in Madras and was briefly with International Centre for Kathakali in New Delhi. Presently, she is a freelance writer on the performing arts. She is the author of 'Guru Gopinath: The Making of a Legend.' |