|   |

|   |

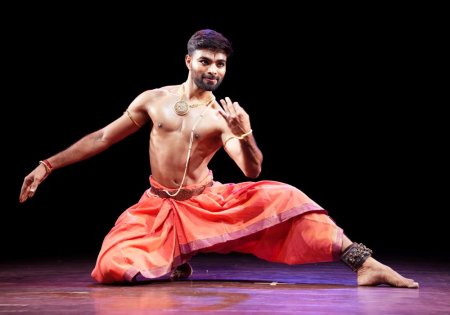

Leela: A Festival of Arts - Satish Suri e-mail: satishism@yahoo.co.in Photos: Prof.K.S.Krishnamurthy June 19, 2025 The festival curated by Shashank Kiron Nair under the banner of Nandanam Art Foundation featured three artistes at the Seva Sadan, Bangalore, on the 17th of May.  Gayathri Guruprasad Gayathri Guruprasad, a senior disciple of Mithun Shyam, presented the opening statement for the festival with the evocative varnam, "Nathanai azhaithu va sakhiye." Set in the majestic Kambhoji raga and adi tala, the piece portrayed the emotional world of a nayika pining from separation from her beloved, Lord Muruga. The composition unfolded as a heartfelt appeal to her confidante, the sakhi, whom she entreated to act as a messenger and bring her Lord to her side. The varnam opened with the nayika's urgent cry, "Nathanai azhaithu va sakhiye endan swami" - "Oh friend, bring my Lord to me." This refrain formed the emotional nucleus of the piece, capturing the intensity of her longing. The nayika questioned whether anyone who truly understood love could bear even a moment of separation, expressing her pain with, "Kadalai arindavar kanam pirivaro?" Her anguish deepened as she wondered whether the Lord's heart had turned to stone - "kallo avar manam kanindurugado?" - unable to melt in response to her sorrow. Throughout the performance, she moved between gentle reproach and desperate pleading. At moments, she chided the sakhi for delaying her mission, and at others, she promised reward, hoping to hasten her reunion with Muruga. These shifts in tone allowed for a nuanced exploration of emotional states - from despair and hope to frustration and devotion. The choreography by her Guru Mithun Shyam provided vibrancy and verve to the presentation. The transitions between narrative and pure dance were handled with finesse, drawing the audience deeper into the nayika's journey. Music on a recorded track was the backbone, supporting the dancer's expressions and movements with clarity and emotive depth while preserving the flow and atmosphere of a live experience. As the varnam progressed, the narrative turned to the glorification of Lord Muruga in the muktaayi swaram. The dancer evoked his divine form - the valiant son of Shiva, riding his stately peacock, radiant with purity and bestowing bliss. This imagery stood in contrast to the nayika's earthly yearning, allowing the performance to traverse from the personal to the divine. Abhinaya brought to life the nayika's inner world - her memories, dreams, and prayers - while rhythmic interludes echoed the unrest of her heart. The Sakhi, though silent, remained a vital presence, representing both hope and possibility. Through this varnam, the performance became a moving expression of viraha bhakti - love in separation - where devotion took the form of romantic longing, and the stage transformed into a sacred space of invocation and surrender.  Sai Venkata Gangadhar Sai Venkata Gangadhar, a senior disciple of Kuchipudi exponent Sandhya Raju, unveiled a transcendent interpretation of "Marakata manimaya chela" that revealed both his technical mastery and spiritual connection to the art form. The rendition was a breathtaking synthesis of poetry, melody, and movement, breathing vibrant life into Oothukkadu Venkata Kavi's timeless kriti. Set in the regal Arabhi raga and anchored in the steady cadence of adi talam, the dancer's interpretation offered a compelling fusion of rhythmic precision and emotive storytelling. From the very first lines of the pallavi, which evoke the emerald-like radiance of Lord Krishna and extol a beauty that surpasses a thousand Cupids, the performance exuded lyrical grace. Through delicate hasta mudras, the dancer conjured the shimmering green of a precious gem, while subtle modulations in posture and gaze conveyed Krishna's playful allure. Particularly striking was the depiction of "Madana koti saundarya," brought to life through nuanced abhinaya that made the divine charm almost palpable. The transition into the Anupallavi and Charanams unfolded with a vivid portrayal of Krishna's mischievous escapades-most notably, the delightfully humorous image of him wiping butter on his lips. This moment was rendered with a light-hearted touch; the dancer's expressive gestures and impish smile drew spontaneous laughter and affection from the audience. Lyrical references to his lotus-like eyes and enchanting smile were presented with refined sensitivity, where each movement resonated with a deep undercurrent of devotion. The rhythmic interludes, structured within the bounds of adi talam, offered space for vibrant nritta. Here, the dancer showcased intricate footwork and crisp, well-calibrated movements that reflected both training and control. The tarangam segment unfolded as the performance's most transcendent moment, where technical mastery and artistic vision merged into something greater than the sum of their parts. As the dancer ascended onto the brass plate, a remarkable transformation occurred - the fluid lyricism of the abhinaya sections crystallized into breathtaking geometric precision. Each precisely placed footfall created resonant metallic punctuation marks in the musical dialogue, while the upper body maintained an almost supernatural stillness, save for the eloquent hands that continued to narrate Krishna's divine play. What emerged most powerfully was the seamless interplay between pure dance and narrative expression. The choreography elegantly echoed the dual nature of Arabhi-its majestic sweep and inherent playfulness. At times lyrical and flowing, at others brisk and percussive, the movement vocabulary remained rooted in the composition's bhakti essence. Even when the choreography leaned into athletic dynamism, the dancer instinctively reoriented the focus towards emotion, never allowing the technique to overshadow the devotional core. Sai Venkata Gangadhar's concluding contemporary piece, titled "Maro prapancham" emerged as a powerful counterpoint to the divine lyricism of Marakata manimaya chela, jolting the audience into confronting modernity's darker spiritual realities. His body became a canvas depicting humanity's tragic descent into addiction's labyrinth - every muscle fibre articulating the slow erosion of willpower under vices' relentless siege. The performance unfolded in three harrowing movements of physical storytelling. Initially, his liquid movements mirrored the seductive allure of intoxication - fingers twitching toward imaginary smartphones, spine arching toward phantom pleasures with the false grace of chemical euphoria. Gradually his motions turned jagged, joints locking in the mechanical repetition of dependency, eyes glazing over in perfect mimicry of digital hypnosis. The most devastating moment came when his entire body convulsed in the paradox of addiction - simultaneously craving and rejecting the poison, fingers scrabbling at his own throat in self-strangulation. Then - like dawn breaking through storm clouds - came the awakening. Gangadhar's torso uncoiled from its defeated slump as if pulled upward by some celestial thread. His trembling hands, moments earlier clawing at emptiness, now formed a fragile mudra. The final moments showed not triumphant liberation but delicate rebirth - each movement tentative yet purposeful, like a seedling pushing through concrete. His closing mudra, fingers brushing awakened eyes, became universal sign language for spiritual resurrection. This wasn't a lecture but an embodied revelation. Gangadhar had weaponized Kuchipudi's expressive vocabulary to create a visceral cautionary tale - the classical abhinaya techniques repurposed to depict scrolling addiction, the rhythmic footwork transformed into the staccato tremors of withdrawal. The piece's brilliance lay in its refusal to judge; it simply showed, with brutal clarity, the exact moment when slavery to vice becomes unbearable to the soul. As the lights faded, the message lingered like a medicinal aftertaste - not "you are fallen" but "you can, like this dancer's body, remember how to rise."  Medha Hari The program concluded with a Bharatanatyam performance by Medha Hari, disciple of Anitha Guha. Medha Hari began her recital with "Bhogindra sayinam," a composition by Maharaja Swathi Thirunal, that unfolded as a compelling opening piece in the recital, establishing an immediate spiritual ambience. Rooted in devotion, the krithi evokes the Ananta Sayana form of Lord Vishnu-reclining majestically on the serpent Adishesha in the cosmic ocean. Set in the raga Kuntalavarali and adi tala, the musicality provided a gentle yet steady framework. The raga's devotional texture lent itself beautifully to the interpretation of Vishnu's divine repose, allowing the dancer to weave in rich visual metaphors: the rhythmic undulations suggesting the Ksheera Sagara, the coiled serpent brought alive through subtle torso movements, and the benevolent presence of Lakshmi at his feet portrayed with tender grace. Each phrase of the sahitya was rendered with care, reflecting the Sanskrit elegance and poetic refinement characteristic of Swathi Thirunal's oeuvre. The dancer's portrayal of Vishnu in Yoga Nidra-resting yet radiating omnipotent energy-was meditative and introspective. The stillness was juxtaposed with inner vitality, a duality skilfully mirrored in the transition between the still abhinaya and the occasional bursts of rhythmic nritta sequences. The use of lasya elements, especially in depicting Lakshmi's quiet service and the reverent offerings of celestial beings, brought warmth and intimacy to the performance. Medha Hari continued her performance with Muthuswami Dikshitar's "Jambupathe" (Yamuna Kalyani, rupakam), a Panchabhuta Linga kriti glorifying Shiva as Jambukeswara, the deity embodying the water element. The composition's lyrical depth-particularly the line "Taapopashamana ambu Ganga Kaveri Yamuna kambu" (He who is the form of water, the Ganga, Kaveri, and Yamuna rivers)-was brought to life through evocative abhinaya, with fluid movements and gestures mirroring the flow of sacred rivers. The choreography skillfully balanced nritta and nritya, employing rhythmic variations in rupaka talam to avoid monotony. The artiste performed the water segment and stood out with her dynamic footwork, an expressive portrayal of the krithi's devotional theme, and seamless transitions between brisk jathis and slower, lyrical passages. The piece's visualization of water-through undulating arm movements, spiralling turns, and liquid like grace-highlighted the dancer's mastery of both technical precision and emotional storytelling. This segment reinforced the recital's spiritual narrative, transitioning from Vishnu's cosmic repose to Shiva's elemental majesty while showcasing the artiste's versatility in interpreting complex Carnatic compositions through Bharatanatyam. Medha Hari's next piece, "Hey Ramba"- a witty composition by Dr. Rajkumar Bharathi-delved into the playful squabbles between Parvati's children, Ganesha and Subrahmanya, with a lighthearted, satirical tone. The choreography brought to life their childish bickering: Ganesha whined about his brother pulling his ears, while Subrahmanya shot back, mocking Ganesha's elephant head. The exaggerated abhinaya-pouting expressions, dramatic gestures of pain, and indignant retorts-turned the divine siblings into relatable, squabbling children. The piece took on an added layer of charm as Medha, drawing from her own experiences as a mother, infused the performance with subtle nuances of parental exasperation and affection. Parvati's intervention-her calm yet firm mediation-was portrayed with a knowing warmth, suggesting the universal struggle to maintain harmony in a household. The rhythmic patterns mirrored the back-and-forth teasing, with quick, playful footwork for the arguments and smoother, flowing movements for Parvati's peacemaking. Humorous yet heartfelt, "Hey Ramba" balanced mythology with everyday family dynamics, leaving the audience both amused and touched by its relatability. The piece closed with restored order, but not without a cheeky hint that sibling rivalry-divine or mortal-is an eternal, endearing truth. Medha Hari's presentation of "Ishopi halahalam" offered a refreshingly irreverent exploration of Shiva's consumption of the poison Halahala. The piece unfolded through a clever interplay of satire and devotion, reframing the cosmic event as a divine being's exasperated response to domestic chaos. The narrative playfully speculated on Shiva's motivations, suggesting his world-saving act might have stemmed from frustration with the constant squabbling between family vahanas - his serpent coiling aggressively around Ganesha's fleeing rat, Kartikeya's peacock fluttering in agitation, and Parvati's lion adding to the pandemonium. The choreography brought this absurdist conflict to life through exaggerated gestures and comedic timing, with the dancer embodying the animal vehicles in almost cartoonish confrontations. As the piece progressed, the tone shifted subtly from humour to pathos. Shiva's decision to drink the poison was portrayed not as a heroic sacrifice but as a desperate escape from unbearable noise, his slow, tortured movements conveying both cosmic significance and divine weariness. The moment of Parvati's intervention - her hands clasping Shiva's throat to stop the poison - became unexpectedly tender, transforming the chaotic premise into a meditation on balance and partnership. This innovative interpretation maintained respect for the sacred narrative while injecting modern sensibility, challenging audiences to reconsider mythic tropes through a lens of humour and humanity. Medha Hari's recital reached its crescendo with a vibrant Thillana in ragam Purvi set to rupaka talam, composed by the legendary Vaidyanatha Bhagavathar. This dynamic finale blossomed from a delicate alarippu-like opening into a breathtaking display of rhythmic virtuosity, where every stamp of her feet resonated like punctuation marks in a poetic declaration of joy. The Purvi ragam's inherent duality - its simultaneous evocation of grandeur and pathos - found perfect expression in Medha's interpretation. Her jathis unfolded like intricate lacework, the rupaka talam's cyclical three-beat pattern providing a framework for both mathematical precision and artistic abandon. Between the scintillating korvais, she wove fleeting moments of abhinaya, her eyes and mudras briefly suggesting the devotional undercurrent beneath the technical display. The final moments saw her body become pure geometry - angles and curves dissolving into one perfect, crystalline pose that hung in the air long after the music ceased. This Thillana didn't merely conclude the evening; it distilled the essence of everything that preceded it - the devotion, the storytelling, the technical mastery - into one radiant, unforgettable moment of pure dance.  Bangalore based Satish Suri is an avid dance rasika besides being a life member of the Music and Arts Society. |